The rationale behind SAirGroup's outbidding

September 1999

By far the most aggressive buyer of airline equity in the past year has been the SAir Group. The company has succeeded in building up a clutch of airline stakes as part of its Qualiflyer alliance strategy. The most recent example of this this was the acquisition of a 20% stake plus an option for a further 10% in South African Airways, and new deals are reported to be in the negotiation stage — with Malev and Transbrasil. The losing bidders in the SAA auction — Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines, American Airlines and David Bonderman’s Texas Pacific Group — would appear to have balked at the price that SAir was prepared to bid for SAA. What therefore allows the SAirGroup to outbid such well–heeled rivals?

SAirGroup is more than just an airline; indeed, the SAirGroup is probably the most diversified airline business in the world. Its key strategy is to extract value from an alliance/equity participation across a group of businesses. As well as the core airline, SAirLines — or as it is more frequently known, Swissair — the SAirGroup contains three other divisions:

- SAirServices, which provides ground handling through Swissport International and aircraft maintenance through SR Technics;

- SAirLogistics, which focuses on freight forwarding and cargo; and

- SAirRelations, which contains the groups’ interests in in–flight catering and sales, and hotels.

In addition, charter and regional airline expertise are pooled in the European Leisure Group, which has a membership that includes Balair, CTA, Sobelair, LTU, Lauda–air, Crossair and Air Europe.

Adding and extracting value

So when SAir approaches a potential investee airline with an alliance proposition and the possibility of taking an equity stake the Swiss company is looking at several income streams — from business sectors such as aircraft maintenance, ground services and catering. It can offer airline synergies as well, but Swissair and its alliance partners will not be able to compete as effectively as Star or Wings in terms of providing network benefits through code–sharing and FFP cooperation.

However, whereas estimating the revenue benefits of code–sharing will always be hit and miss, a contract with SAir’s Gate Gourmet in–flight catering company guarantees future income for the SAirGroup, as well as providing concrete cost savings and probably an improvement in the in–flight product to the investee airline. Similarly, it is possible to calculate with a fair degree of certainty the revenue benefits and cost savings associated with using SAir’s specialist subsidiary, Nuance, to manage in–flight sales.

Another major area of cost savings regularly claimed by alliances is the joint purchasing of aircraft. Here the SAirGroup is the only one of the alliance lead–airlines that can offer an established vehicle for this activity. Through its joint venture with GATX Corporation, SAir’s Flightlease now owns, leases and manages the majority of the aircraft in the Swissair and Balair/CTA leisure fleets. Thus one of the potential benefits to a smallish airline of joining Qualiflyer is from lower aircraft rentals and extra operational flexibility.

Of course, other airlines and alliances can offer some of these non–airline benefits as well. Lufthansa has its own third party maintenance division, (Lufthansa Tecknik) and its own catering company (SkyChefs, the global market leader over Gourmet). But at most major airlines, these peripheral businesses are usually classified as “separate business units” (SBUs) which means that, in practice, they rely on their parent airline for survival. Internal charging is not necessarily at market rates and the parent airline will often demand preferential treatment.

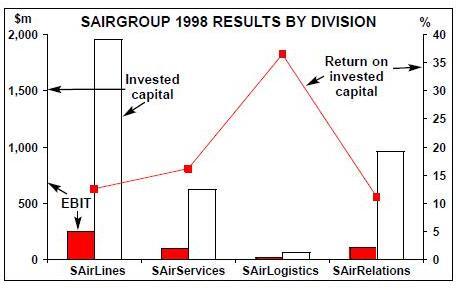

The set–up at SAirGroup is different. Each company within the SAirGroup bears responsibility for its own bottom–line results. The companies operate autonomously, though they are expected to identify and exploit synergistic potential among Group member companies, and to cross–sell all the Group’s products. The reliance that SAir has on its affiliates (SAirRelations accounts for nearly a quarter of the total Group’s invested capital) means that it can claim to be more “customer- focused” than its airline rivals.

Moreover, SAirGroup has also adopted a fairly transparent approach in accounting, giving quite detailed financial information on each of its divisions.

Intra–Group business is expected to be conducted at general market rates. Each company has a return on invested capital (ROIC) target. Interestingly the ROIC target for the SAirLines’ division in 1998 was 8% while for the entire SAirGroup the target was 12%.

The fact that SAir can offer such a diversified range of services is particularly valuable to airlines that are privatisation candidates. This was undoubtedly part of the reason that the Portuguese government has adopted SAir as an alliance partner for TAP. The theory is that the combination of cost savings, revenue enhancements and productivity gains from an association with SAir will enhance the value of TAP’s shares when they are floated on the Lisbon stock–exchange.

Swiss downsides

And what of the downside of SAir’s strategy? First, it tends to eat up capital, which SAir’s balance sheet can bear but which does not endear the company to stock–market investors (who at some point in the future may demand the break–up of this conglomerate- like structure).

Second, it may be exposing SAir to competition from low–cost, non–airline specialists in maintenance, catering, etc..

Third, all the associated businesses move in the same cycles as the core airline operation, giving SAirGroup little protection in a recession.

Finally, it should be remembered that SAirGroup’s strategy was born out of necessity; it was designed to overcome Swissair’s inherent disadvantage as a very high cost airline with a restricted home market. That disadvantage is still at the heart of the SAirGroup.

In the first half of this year SAirGroup reported a disappointing SFr84m ($56m) operating profit. Non–airline activities contributed 46% of total revenue but 69% of consolidated operating profit. Airline activities risk becoming a loss–leader in SAir’s strategy.