Air Canada/Canadian amalgamation - dilemmas, dilemmas

September 1999

The Canadian government in mid–August announced that it was extending Air Canada and Canadian Airlines a temporary antitrust immunity of sorts in order to allow them to chat about some form of amalgamation, purchase of international rights or less expensive ways of managing the Canadian domestic market. This might seem momentous, but it is in fact the fourth time that the two carriers have met, usually secretly, to discuss these issues. A productive outcome is still very unlikely from whichever perspective one looks at the problem.

From the Canadian government’s perspective, presiding over a merger, whether actual or virtual, would be politically embarrassing, signalling the first failure of an airline deregulation policy. Since there are no nationwide scheduled jet carrier alternatives, any amalgamation of the big two on domestic markets would mean an effective monopoly. And this monopoly could only be made more palatable for the Canadian taxpayer if the government were to re–regulate the domestic market, including fare setting and imposing market access and capacity rules. Many smaller markets (i.e., most of Canada’s domestic segments) would also have to be overseen and minimum service levels guaranteed year- round. This solution would be messy, to put it politely.

Alternatively, either carrier could give up its domestic system (including regional airline affiliates) and go purely international but a guaranteed feed agreement would have to be put in place. This would still produce a domestic monopoly, unless the Canadian government could successfully encourage the emergence of a third force for the first time since full Canadian deregulation in 1988. WestJet (see Aviation Strategy, October 1998 and August 1999) shows promise but it is still a small operator compared to the incumbents.

Air Canada’s objectives

From Air Canada’s perspective, the simple objective is to gain the status of the single Canadian international scheduled flag carrier. It very quickly made an offer to buy all of Canadian’s international services, but the proposal was rejected.

However, if Air Canada were to buy Canadian Airlines in any form, it would risk making that same mistake that Canadian made when it bought Wardair back in the late 1980s. At that time Canadian thought that this airline would be the final key addition to the new carrier that itself had been formed from a merger of CP Air, Pacific Western and other smaller companies. Canadian dumped the incompatible fleet but also very popular Wardair brand. The value of Wardair to Canadian was perceived to be access to key European markets like London, Paris, Frankfurt from which they were excluded at the time.

But after the take–over, the Canadian government designated additional charter carriers on the key European points in an effort to promote competition, so undermining the value of the new route rights. At the end of the day the Canadian Group was forced to swallow C$500 million of debt that it could not afford. This is the fundamental reason why Canadian has been in perpetual reorganisation and has teetered on the brink of extinction so many times.

So if Air Canada were to buy Canadian outright or purchase all the international services, the government would at some point feel obliged to accommodate competing services, and Air Canada would probably end up in the same state as Canadian is today. A better option for Air Canada would be some form of asset stripping of Canadian’s international route system.

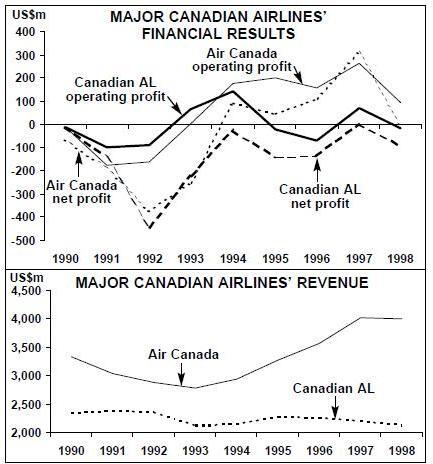

As Air Canada has most of what it needs in Europe and there is little of interest in Canadian’s US network (with the possible exception of some slots at congested US airports), all Air Canada’s interest should be focused on the Asian routes. The question is, as usual, what would Air Canada have to pay for these routes? As noted above, Air Canada’s first offer (for an undisclosed amount) for the international routes was rejected, but Air Canada’s resources are limited because of its own financial problems. A large cash outlay for any route purchase paired with a recession of any significance should be a serious concern for Air Canada management and shareholders.

The AA/CP perspective

Canadian Airlines’ perspective is really that of American Airlines, which owns 33% of the shares and 25% of the voting rights. When American bought into Canadian, it saw three main advantages. First, there was the cash flow that would result from the large management contract that Canadian signed with American and Sabre Decision Technologies. But because of the ongoing financial crisis, Canadian was never able to pay the fees it was supposed to. Second, there was potential route synergy to be achieved by joint operation in the new Canada/US open skies environment. But the AA/CP transborder partnership has produced limited results when compared to the Air Canada/United alliance.

Third, there was access to transpacific markets via the Vancouver gateway, which unfortunately was put together just in time for the Asian recession. But now that that Asian economies are clearly recovering, it would seem that the AA/CP gateway concept is poised to turn profitable.

Onex and American

There are widespread and probably justified suspicions in Canada that American is attempting to capitalise on its investments by its participation in the Onex consortium, and in the process gain a key position in a unified Canadian carrier. Onex Corp. an investment company, has made a C$1bn (US$700) proposal to purchase stock in the two Canadian airlines and then merge them, leaving Onex with about 31% of the new airline. AMR Corp is supporting the bid by contributing C$500m (US4335m) in equity and loans to the Onex bid (although, surprisingly, American has stated that it wishes to sell off its approximate 15% stake in the new airline within a few years).

Early indications are that Air Canada will try to put a poison pill in place to neutralise Onex, and powerful union and governmental voices are being raised in opposition. If Onex fails, will American then make one final attempt to revitalise Canadian through a new round of investment (which would probably require the Canadian government to liberalise its laws on foreign investment)?

It would have to find a way to reduce significantly the operating costs of Canadian, and probably change its infrastructure in Canada. Most of Canadian’s operating systems are already managed by American so a significant reduction of management staff and a DFW–based remote–control management structure should be feasible. In addition, Americans older MD–80s (and/or ex–Reno aircraft) could be deployed to replace CP’s 737s.

This strategy would probably put Canadian in a break–even position domestically. Then an improving Asian market and a concentration on some key profitable European routes (specifically the UK) should produce some profit at the company level. Equally importantly, American’s strategic interests in the Pacific would be protected (though its new stake in Canadian would still have to be limited to comply with Canada–Asia bilateral ownership clauses).

Once Canadian has exhausted all of the options with Air Canada and/or Onex, it can tell the government that the American investment routes is the only one possible. And the loss of sovereign control should be more attractive to the government than the alternatives — bankruptcy of a major employer, a government bail–out or the creation of a domestic monopoly.