Continental: balancing rapid growth and profit margins

September 1998

Since staging one of the most impressive financial turnarounds seen in the US industry three years ago, Continental has gone from strength to strength. Its profit margins have continued to improve, despite extremely rapid international growth and an ongoing process of bringing wages to industry standards. How much longer can expansion continue at such a rate? And how is the carrier offsetting the substantial hikes in labour costs?

Continental emerged from its second Chapter 11 visit in April 1993 with the help of a $450m investment from Air Canada and Air Partners LP. The reorganisation involved extensive job and route cuts, slashed long–term debt from $5.6bn to $1.7bn and improved the cash position to $650m. The airline emerged with low unit costs but also low yields.

But financial recovery was delayed because of the ill–fated Lite experiment, launched in October 1993. The high–frequency, short haul, low–cost venture was expanded rapidly to account for 60% of Continental’s system–wide departures. But it never made a profit and it brought Continental to a serious liquidity crisis in early 1995.

Lite failed mainly because the strategy was poorly executed. It was expanded too fast. The venture was dogged by operational problems, low load factors, poor revenue–generation, high transition- related costs and confusion about branding.

The failure led to the resignation of CEO Robert R. Ferguson III in October 1994. He was replaced by Gordon Bethune, the current chairman and CEO, who had joined the company from Boeing nine months earlier. Bethune has been credited for Continental’s subsequent financial turnaround. He introduced a new corporate strategy, aimed at improving customer service, strengthening hub operations and eliminating excess capacity. He also brought in his own team to tackle areas like pricing, scheduling, distribution, human resources and finance.

The new strategy involved scrapping Lite, transferring the capacity to the main hubs and bringing back first class. The 21–strong A300 fleet was phased out. About 4,000 jobs, or 12% of the total, were eliminated and two maintenance facilities were closed in favour of outsourcing. In his first five months as CEO Bethune also oversaw a debt restructuring that deferred $370m in payments. Overall, renegotiated debt, aircraft deliveries and leases added up to $500m–plus savings in payments by the end of 1996.

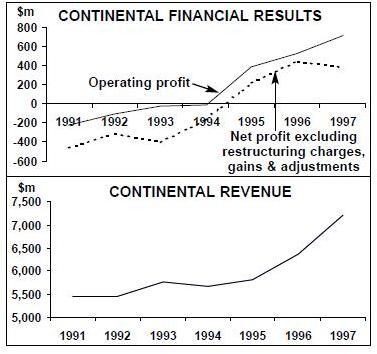

The result was an immediate return to profitability in the second quarter of 1995. For that year Continental reported net earnings of $224m — its first annual profit since 1986 and quite a contrast to the previous year’s $613m loss. The recovery was attributed to sharp load factor and yield improvements — after that both were close to the industry average. This more than offset the inevitable rise in unit costs (due to Lite’s elimination), although the hike was limited to just 5% in 1995. The turnaround was consolidated with a net profit of $319m in 1996, which included a one–time $128m fleet–related charge and $97m of profit sharing and on–time bonuses. This was followed by a $385m net profit in 1997 (including $126m of profit sharing and on–time bonuses) and a $244m net profit in the first six months of 1998.

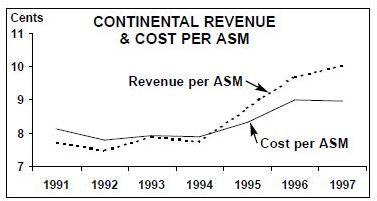

The past 18 months’ healthy profit growth and 10–11% operating profit margins were significant achievements in a period of major expansion. After a 10% capacity decline between 1992 and 1995 and virtually no growth in 1996, Continental’s ASMs surged by 10% in 1997 and by 11.7% in the first six months of 1998. It is currently the fastest–growing of the US major carriers.

The results are also impressive because they include hefty income tax provisions — the company had to resume paying income tax in 1997 after using tax credits for two years. And the profits were achieved despite a substantial rise in labour costs (due to a new pilots contract) and reduced earnings at Continental Micronesia since late 1997.

Continental attributes its success to strong revenue performance, record load factors and its ability to remain at or near the top of the industry’s on–time performance and other service quality rankings. Despite the rapid expansion, the yield has remained essentially flat. Although unit costs have risen further (9.07 cents per ASM in 1997), the hikes have been minimised by higher aircraft utilisation, productivity improvements and reduced aircraft ownership costs.

By the end of 1996, Continental had more than $1bn in cash and short–term investments. It has paid debt early, reduced high–interest debt, invested heavily in hubs and, since early 1997, repurchased common stock or convertible securities. Its cash balance was $1.2bn at the end of June 1998.

Much of Continental’s success must be attributed to improvements in operational performance and reliability. After coming near the bottom of the DoT’s customer service rankings for many years, in 1996 Continental found itself among the top three on all the criteria. Except for some recent hiccups (blamed on bad weather and inaccurate block–time estimates on new services), the carrier has consistently maintained those high rankings.

How was Continental able to accomplish that? Accelerated fleet renewal has obviously helped. Also, in early 1995 the company appointed two senior executives to oversee the task. And it began offering bonuses to workers each month when the company met targets related to the DoT’s on–time statistics. Last year it paid $21m in bonuses, which was $490 per employee.

Morale has also been boosted by the introduction of profit–sharing (about 7% of annual wages over the past two years), continued pay rises, special prizes for perfect attendance, senior management’s open–door policy, informal atmosphere and programmes to improve teamwork.

Continental has achieved much success with its BusinessFirst product, which copied Virgin Atlantic’s strategy (first class at business class fares, sleeper seats, personal videos) and was first introduced on the transatlantic and later in US transcontinental markets. The product has helped improve customer mix: the business traveller content of total traffic has risen to the mid- 40s from just 32% in 1994.

Hub and growth strategy

Since Lite was dismantled, Continental’s strategy has focused on strengthening what it calls its “underdeveloped franchise hubs” of Houston and Newark and Cleveland. In contrast to many of its competitors, it is fortunate in having considerable spare capacity at its main hubs and is right in the middle of a major international growth spurt.

The original (summer 1996) expansion plan envisaged 2.8% annual growth in domestic capacity and 8.2% internationally, but those rates have been exceeded. In 1997 domestic ASMs rose by 4.5% and international ASMs by 23.6%. This year’s growth looks likely to exceed last year’s, as at least 13 new international destinations will have been added by year–end, plus new services to Japan from Houston and Newark in November and December.

Since the summer of 1995, the number of destinations served by the carrier from Houston, Newark and Cleveland has increased by 40–44%. Continental quite justifiably feels confident at present that, given the potential still offered by its hubs, it can continue to grow rapidly while maintaining healthy profit margins. The carrier says that growth will return to the industry norm once the hubs are fully utilised.

However, Continental’s president Greg Brenneman recently made it clear that profitability would not be sacrificed. He said that growth would continue as long as operating margins can be maintained at around 10%. Should it turn out to be necessary to slow down, the fleet retirement programme offers much flexibility. The latest cutbacks in Micronesia will actually reduce next year’s overall ASM growth by about three points, to 8.4%.

International expansion and alliances

Continental has strengthened its presence on the North Atlantic. After introducing services to Dublin, Shannon and Glasgow earlier this summer, the carrier now serves 13 cities in eight European countries, accounting for about 10% of the Majors’ total ASMs. Continental’s capacity rose by 58% in 1997, which meant that it overtook Northwest and TWA. Despite the rapid growth, the routes are performing well in terms of unit revenue and earned a $125.5m operating profit in 1997.

Last year Continental expanded its 1994 marketing alliance with Alitalia and earlier this year began code–sharing with Virgin and Air France. The deal with Air France, which was originally signed in October 1996 but had to wait for a new US–France ASA, holds much promise in that it will give Continental extensive access to beyond points in Europe, Middle East and Africa. Codesharing with British Midland on Manchester- Scotland flights began in mid–August.

The Virgin code–shares have given Continental welcome access to Heathrow, which the carrier is keen to start serving from its three main hubs once the aeropolitical situation is sorted out. It also hopes to add Cleveland–Gatwick services in 1999.

But Continental’s biggest efforts have focused on Latin America, where it has expanded aggressively over the past two years. In 1996 and 1997 the carrier entered Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Brazil and Venezuela and expanded substantially in Central America. This year has seen further expansion to Venezuela, Aruba, Chile, Mexico and other parts of Central America.

Two years ago Continental overtook United as the second largest US carrier in terms of passengers and cities served in Latin America. The latest additions in June made it equal with American in terms of flights operated in the US–Central America market. Continental’s Latin American network now covers 37 cities in 21 countries.

The two–pronged strategy of promoting Houston as an alternative to congested Miami and Newark as a convenient gateway for New York area’s large Hispanic population appears to be working. Continental’s Latin America operating profit multiplied tenfold to $43m last year, and the carrier appears not to have experienced any of the recent weakness reported by American. Its unit revenues on existing routes have been flat (compared with American’s 10% decline) and new services are apparently running ahead of profit projections.

However, the overcapacity now evident in many US–Latin America markets may shift emphasis in favour of co–operating with the region’s carriers. Since losing Aerolineas Argentinas to American last year, Continental has purchased a 49% stake in Panama’s COPA (completed in May), agreed to acquire a 19% stake in Colombia’s ACES (May) and begun code–sharing with Vasp (July 1).

The future code–shares with COPA from Miami and Houston will enable Continental to benefit from Panama City’s location as a gateway between the Americas and proven success as a hub. Co–operation with ACES will boost feed on its daily Houston–Bogota and Houston–Medellin routes, and tie in Continental with a good quality and very ambitious Andean market carrier.

Continental’s Asian exposure has so far been limited to its Micronesian subsidiary, which accounts for only 6% of its revenues, but the situation is now changing with the forthcoming daily non–stop services from Newark and Houston to Tokyo, extensive future code–sharing with Northwest and development of co–operation with Asian partners. Codesharing with EVA began in March on the Taipei–Los Angeles sector and a similar arrangement with Air China on US–China routes is expected this autumn.

In response to the Asian crisis, Continental has transferred aircraft from Guam to its mainland hubs. Pacific capacity was cut by 14% in the June quarter, and the company has just decided to retire early the four–strong 747 fleet used by Continental Micronesia, replacing them with DC–10s.

Fleet rejuvenation

Continental is in the process of rationalising and modernising its fleet, which still includes about 15 different models covering virtually the full range of the jets currently offered by Boeing. The aim is to have the youngest domestic jet fleet in the industry, with an average age of 7.2 years (13.8 years at present), by the end of 1999.

The earlier A300s were replaced by 757s. The Stage 2 727s, 737–100/200s and DC–9s are due to leave the fleet by the end of next year. The MD- 80s will stay as most were taken on 18–year operating leases. The four remaining 747s utilised in Guam will now be retired next April and the 13- strong Pacific 727 fleet will go by December 2000. These decisions will result in a $77m after–tax charge in the current quarter. The Stage 2 narrowbodies are being replaced by the various new generation 737 models ordered over the past three or four years. The remaining fleet of 36 DC- 10s will be replaced by the 777s and 767s.

The airline is due to receive 64 new Boeing aircraft this year. The first 124–seat 737–700 entered service in April, primarily on Latin American and transcontinental routes from Houston and Newark. In July Continental became the first US carrier to operate the larger 737–800. In March it ordered 15 737–900s, for delivery in 2001–2002. Regional subsidiary Continental Express is in the process of moving towards an all–jet fleet over the next five years. It launched the 50–seat ERJ–145 last year and recently ordered 25 37–seat ERJ–135s, for delivery from July 1999.

Labour and other challenges

Continental has enjoyed relatively amicable labour relations, in part because of the gradual process of restoring wages to industry standards. But the situation heated up in 1997 when the pilots, whose salaries were still 20% below industry average, entered new contract negotiations and demanded a huge settlement in the wake of the company’s record 1996 earnings.

The company essentially gave in on the economic issues, granting the pilots an immediate 20%-plus pay rise (retroactive to October 1), further 7.5% rises in 1998 and 1999 and improved pension benefits. The deal was designed to restore pay levels to the average of the five largest majors over five years. The final five–year contract, which took another seven months to sort out (signed in June 1998), also included the job protections that the pilots had sought in the wake of the announcement of the alliance with Northwest. In return, the pilots gave up profit–sharing and agreed to maintain the productivity advantages that Continental currently enjoys over its competitors.

To offset most of the resulting 27% increase in pilot payroll costs this year, Continental outlined a $100m package of cost cuts for 1998. The programme is apparently on target, with the savings coming mainly from travel agent commission cuts, electronic ticketing and lower interest rates on aircraft financing.

But the problem is that the pilot contract and other labour deals will maintain pressure on labour costs for many years to come, while Continental has already accomplished its easiest cost–cutting and obviously does not want to implement cuts that would affect service. About a year ago it formally promised its workforce to bring wages and salaries (before profit–sharing and bonuses) to industry standards within three years. The dispatchers’ union secured a new five–year contract on that basis in June 1998, but talks with major groups like the flight attendants are yet to come (their current contract becomes amendable at the end of next year).

The “virtual merger” between Northwest and Continental, which would involve Northwest purchasing Air Partners’ existing 14% stake in Continental and extensive code–sharing and cooperation between the two carriers and their global partners, is currently in limbo due to regulatory delays and Northwest’s difficult labour situation. The knowledge that it will take Northwest quite a while to repair its customer service and image after the labour dispute is settled must be an By Heini Nuutinen added frustration for Continental.

| Current fleet | Order(options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | ||

| 727-200 | 30 | 0 | To be retired by end of 2000 | |

| 737-100 | 6 | 0 | To be retired by end of 2000 | |

| 737-200 | 17 | 0 | To be retired by end of 2000 | |

| 737-300 | 65 | 0 | ||

| 737-500 | 61 | 6 | 6 in 1998 | |

| 737-700 | 8 | 42 | 1 in 1988, 9 in 1999, 8 per year to 2003 | |

| 737-800 | 4 | 24 | 11 in 1999, 13 in 2000 | |

| 737-900 | 0 | 15 | 8 in 2001, 7 in 2002 | |

| 747-200B | 4 | 0 | To be retired in April 1999 | |

| 757-200 | 29 | 4 (25) | 1 in 1999, 3 in 2000 | |

| 757-200EM | 3 | 0 | ||

| 767-400 | 0 | 26 | For delivery in 2000-2004 | |

| 777-200 | 0 | 10 | 5 in 1998, 5 in 1999 | |

| 777-200ER | 0 | 4 | 1 in 1999, 3 in 2000 | |

| DC-9 | 28 | 0 | To be replaced by 767s and 777s | |

| DC-10 | 36 | 0 | To be replaced by 767s and 777s | |

| MD-80 | 69 | 0 | ||

| TOTAL | 360 | 131 (25) | ||