Cathay Pacific: surviving the Asian maelstrom

September 1998

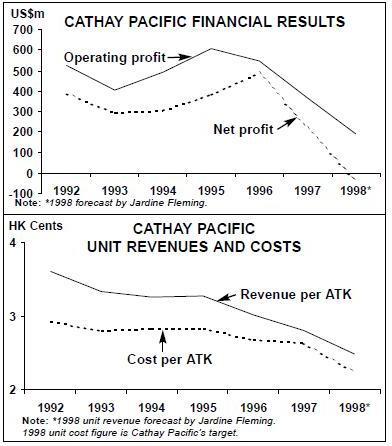

Cathay Pacific finds itself at the centre of the Asian maelstrom, reporting a loss in the first half of 1998 for the first time since its public flotation in 1986. Nevertheless, Cathay’s strategy of repositioning for the upturn is the only logical, coherent response to the crisis.

Red numbers are a serious shock to Cathay Pacific managers (until recently they were concentrating on trying to get profit margins back up to the 15–20% mark) and to Asian stock–market analysts. But compared with the losses produced by US majors and European flag–carriers in their 1992–94 slump, the results do not look too disastrous. Net profit for the first six months of 1998 was HK$175m (US$22.5m), and the company maintained dividend payments of HK$102m so the retained loss for the period was HK$277m ($35.7m), representing a margin on turnover of -2.1%.

Operating cashflow halved compared with the same six–month period in 1997, but at HK$1.6bn ($206m) was still equivalent to 12.6% of revenue. But Cathay’s balance sheet is still strong: at the end of June shareholders’ funds totalled HK$25.3bn against net debt of HK$12.7bn, a debt/equity ratio of 33:67.

However, over the past year Cathay has spent about HK$456m on buying and retiring its own shares in a vain attempt to support its stock–market value. (The Hong Kong government itself is now intervening in the stock–market, buying blue chip shares — including Cathay’s — in order to fight off currency speculators.)

At the beginning of 1997 the stock–market capitalisation of Cathay was about HK$42bn ($5.5bn); by August 1998 it had more than halved to HK$20bn ($2.6bn). As price/earnings multiples are of no use in the present market, Asian stock–market analysts have been concentrating on adjusted break–up values for airlines in the region.

In Cathay’s case the theoretical value of the owned fleet, using latest appraisers’ estimates and even allowing for a decline in widebody prices, would be around US$5.4bn; the company’s net debt at midyear was the equivalent of US$1.6bn, implying an unadjusted net asset value of US$3.8bn.

The share price is, therefore, trading at a discount of about 30% to this asset value. As Cathay is not going to go out of business, dumping its fleet at distress prices, the stock–market is implying that the secondhand value of widebodies is much lower than is explicitly recognised by airline and aircraft traders.

Cathay has first–hand experience of this phenomenon. It attempted to sell its 747- 200s, but negotiations with Qantas fell through when the Australian carrier found cheaper equipment from other Asian airlines. Two were leased out to Virgin Atlantic, another three have been parked, and the other two plus the -300s are believed to be on the market.

Worst of all possible worlds?

Because Cathay normally does much better in the second half of the year, the full year loss is forecast to be around the same level as in the first half — Peter Tang of Jardine Fleming is opting for HK$274m, for example. The big question is whether this represents the bottom for Cathay or whether there is worse to come?

Cathay is operating in the worst of all possible worlds. The other Asian carriers have seen their traffic slump but they have also benefited from increases in yield as their currencies have devalued. With the Hong Kong dollar pegged to the US dollar, Cathay has suffered both traffic decline and severe yield erosion, resulting in passenger unit revenues collapsing by 22%.

The major problem area has been North Asia, which encompasses the two countries where Cathay has traditionally made most of its profits — Japan and Taiwan. Over the past year the yen has depreciated by 20% against the Hong Kong dollar, the Japanese economy has lurched into recession and Japanese tourists have also been put off by the threat of chicken flu. In the first quarter of 1998 Japanese arrivals in Hong Kong were down 60% on a year ago, which is the most important factor behind an anticipated fall in overall tourist arrivals of at least 10% this year, following on from a decline of 17% in 1997.

In the Taiwan market yields have also been impacted by the decline of the Taiwan dollar, but Cathay has also come up against increased competition from EVA and China Airlines, which has been discounting deeply to recapture business in the wake of its A300 crash in March.

The Hong Kong outbound market is suffering as well because of the parlous state of the economy — GNP is forecast to fall by up to 4% this year compared with 1997. Those businessmen who are still travelling are downgrading, further undermining Cathay’s yield (in 1996 40% of the airline’s Hong Kong–originating revenues were in First and Business Class).

Cathay’s response

Cathay’s yield erosion is not just due to foreign exchange effects: it has been chasing low–yield traffic, especially sixth freedom traffic, to fill its aircraft. This makes it all the more critical for Cathay to adjust rapidly to the new Asian operating environment, which means moving from being a relatively high–cost airline to being competitive with, at minimum, SIA. Its own target is to reduce unit operating costs by 12% in 1998 to HK$2.24 per ATK from HK$2.57 in 1997.

The indications are that this target may be met — Cathay’s operating unit cost was HK$2.33 in the first half of this year. Unfortunately, the main reason behind the unit cost decline was the fall in fuel prices, down by 27% on an ATK basis whereas Cathay’s unit labour costs were reduced by just 5%.

Cathay appears very reluctant to take the type of labour cost measures that commercial Western airlines have adopted in severe recessions. It hopes that staff reductions of 5–7% can be achieved through natural attrition, but this will only take about HK$500m or 2% a year out of its operating costs. More drastic action seems inevitable.

While the rapid depreciation of the Asian currencies against the Hong Kong dollar has been a disaster for Cathay’s yields, at least it has not had to cope with the exchange rate effect on US dollar–related debt, which has wrecked the balance sheets of the other Asian airlines over the past year.

Consequently, Cathay has not been under the same pressure to defer or cancel orders, and has taken all its deliveries on schedule. This year Cathay has taken delivery of three A340–300s and two 777- 300s (as launch customer). Another five 777s and three A330/340s will be taken, as planned, over the next 12 months — unless the speculators finally force a serious devaluation of the Hong Kong dollar and Chinese yuan.

Peter Sutch, Cathay’s chairman, describes the airline’s strategy as “positioning to benefit from the next market upswing” — the only rational reaction to the current crisis.

Cathay is building up capacity on routes to destinations outside Asia, specifically to North America. In December 1998 it will start a daily A340 San Francisco service to add to the twice–daily 747 Los Angeles, daily 747 JFK, daily 747 Vancouver and daily A340 Toronto services. At present Cathay is again being forced to buy passengers on these routes — its US$399 round trip fare on offer in the US is a huge bargain — but it is clearly developing a route structure to North America that will allow it to sell itself as the major hub carrier connecting the Pacific with Southeast Asia.

Because Cathay was a higher cost airline than all other scheduled Asian carriers, except China Airlines, JAL and ANA, it was until recently very reluctant to compete fully on the Pacific (it only started flying to San Francisco, which has a huge Chinese population, last December).

Now Cathay is emphasising its competitive edge over SIA. Whereas SIA is waiting until 2001 for its ultra–long–haul A340- 500s, Cathay can now operate non–stop to most North American destinations (even some of its New York JFK flights, routed over the Pole, are non–stop). The North American network now balances its Europe operation to London, Manchester, Frankfurt, Paris, Amsterdam, Zurich, Rome and Istanbul.

In competing with the US majors, particularly United, Cathay is re–emphasising its strong selling point — service quality. The current campaign is dubbed “Service straight from the heart”, which means, among other perks, a personal TV in every seat.

Premier Chinese airline

In the chaos that is the Asian market at present, it should be remembered that Cathay is the premier Chinese airline, positioned to be the leading carrier of international air traffic to/from China, however quickly or slowly that potentially huge market develops. Cathay’s main shareholders are:

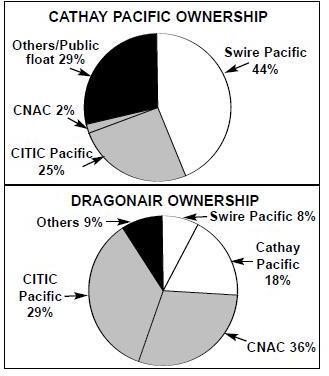

- Swire Pacific (with about 44%), the publicly quoted arm of the Swires Group, which has extensive mainland Chinese interests in engineering, brewing, property development, etc.

- CITIC Pacific (with about 25%), the Hong Kong subsidiary of the mainland Chinese investment vehicle, CITIC.

- CNAC (with about 2%), the Hong Kong subsidiary of Beijing–based CAAC, which is the ultimate owner of the mainland Chinese airlines and the regulator of the aviation industry.

In turn, Cathay is still closely linked with Dragonair, the main Hong Kong–mainland China airline. Early last year Swires and CITIC Pacific each sold 17.7% of Dragonair to CNAC, which is now the major shareholder with 36%. Swire Pacific and Cathay together have about 26% of Dragonair and CITIC Pacific 29% (see charts, page 12). CNAC also has a 51% stake in Air Macau.

This structure establishes Cathay’s position within the “one country, two systems” framework. Although CNAC wants to maximise Dragonair’s growth prospects, the cross ownership of CITIC and Swires is intended to minimise unnecessary competition.

In combination with Dragonair, Cathay can claim to offer the best service to all Chinese points from Europe and most Chinese points from the US — and the Chinese points include Beijing and Taipei. This is Cathay’s longer–term strategic strength, which has also been reinforced by the move from Kai Tak to Chep Lak Kok airport.

The opening of the new airport at Chep Lak Kok was, almost inevitably, a farce, and the temporary embargo on cargo traffic that Hong Kong Air Cargo Terminals was obliged to impose has caused more financial pain for Cathay. But once CLK overcomes its teething troubles, as it soon will, its passenger and cargo facilities will rival Changi.

No way BA/AA?

From this perspective, Cathay’s attitude towards alliances becomes more understandable. At the half–year results briefing Cathay management was explicit on the widely rumoured sale of a stake in the airline to British Airways — “categorically no plans”. This rebuff must be a disappointment to BA, which would undoubtedly like to recapture the share in Cathay it short–sightedly sold in the early 1980s in order to pay for its redundancy programme.

An investment in Cathay would provide British Airways with an introduction into the Chinese market, a medium- to long–term investment; it would counter Lufthansa’s recent successes in the region, notably its alliance with SIA; it would tie up another of the Europe–Australasia routings; and it could strengthen the weak Pacific link in BA/AA’s global network (American is very weak compared with United, Northwest, Delta and Continental on the Pacific).

For Cathay the attraction of an alliance with British Airways is evidently less clear. Indeed, Cathay executives have carried out the network analyses necessary and concluded that the bottom–line benefits were not at all tangible. Here, one can observe the Swire mentality in action — whether the executives are British or Chinese, they refuse to be influenced by current management trends, and only make decisions which can be proved to materially improve Cathay’s position. And, as Cathay executives never fail to remind outsiders, Swires has been trading successfully with the Chinese since 1866 and, by implication, really does not need outside help.

Also, CNAC would likely object to Swires selling to Europeans when the explicit aim of the Swires Group is to get closer to Beijing in the post–hand–over environment. Perhaps most importantly, the Swire Group will simply not sell at the bottom of the market.

Star is not obviously any more attractive to Cathay than BA/AA. Indeed, it would be difficult to see Cathay coming to an accommodation with United on the Pacific as it is so committed to building up its own presence on these routes. Also, Lufthansa’s connection with SIA could be problematic. SIA is encroaching on Cathay’s home territory and has established a good relationship with CNAC (it used to provide top executives on secondment for Air Macau). Then in August 1998 SIA announced a purchase of a 5–10% stake in China Airlines as part of a comprehensive alliance that will probably include direct management involvement in Taipei and fleet rationalisation, with China Airlines taking some of SIA’s early 777 deliveries.

But while grand alliances are out, tactical tie–ups will be pursued. For example, Cathay and Swissair have just set up a code–share on Zurich–Hong Kong, and further joint ventures are likely on the thinner European routes — perhaps with KLM on Amsterdam.

| Capacity | Traffic | Load Factor | Yeild | Unit Revenue | |

| (ASK) | RPK | % pts | per RPK | Per ASK | |

| Europe | -1.9% | -5.5% | -2.8 | -13.5% | -16.6% |

| Pacific/South Africa | 6.9% | -4.5 | -18.5% | ||

| 0.4% | -23.4% | ||||

| North Asia | -5.1% | -12.4% | -5.0 | -18.5% | -24.8% |

| SE Asia/Middle East | 7.8% | -3.2% | -6.6 | -14.4% | -22.8% |

| Total passengers | 2.7% | -4.1% | -4.7 | -16.9% | -21.6% |

| Total cargo | 2.9% | 2.9% | -4.0 | -5.9% | -11.2% |

| Current fleet | Order(options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | |

| 747-200 | 7 | 0 | All for sale, or being leased out |

| 747-300 | 6 | 0 | All for sale, or being leased out |

| 747-400 | 19 | 0 (6) | Options for delivery in 2001-02 |

| 747-200F | 7 | 0 | Three leased out to Air Hong Kong |

| 747-400F | 2 | 0 | |

| 777-200 | 4 | 0 | |

| 777-300 | 2 | 5 (10) | Two in 1998, three in 1999 |

| A330-300 | 11 | 1 (9) | Delivery in 1998. Options interchangeable |

| with A340s | |||

| A340-300 | 9 | 2 | Delivery in 1998 |

| TOTAL | 67 | 8(25) |