Time to legitimise the grey market for slots

September 1998

The European Commission and the UK’s Office of Fair Trading (OFT) are at loggerheads over whether British Airways should be able to sell the 267 slots it must dispose off in order to go ahead with its alliance with American.

After a period of consultation, the UK’s Department of Trade and Industry will announce on September 4 whether it agrees with the OFT’s recommendation that BA should be able to sell the slots. If (as seems likely) the Department does agree and the Commission does not back down on the view it gave in its Official Journal that slots should be given up “without compensation, whether financial or not”, BA is likely to go ahead and sell the slots. If the Commission still wants to stop the sale, its only option will be to take the UK government to the EU Court of Justice.

The eventual outcome will impact on more than just BA, because in effect it will legitimise or not the current grey market for slots that exists at Europe’s slot–constrained airports.

The grey process

At present, if airlines want slots at congested airports the grey market is the only alternative to the official allocation process. What happens is that one airline will approach another with a wish–list of slots it wants to acquire. If the other airline is willing to give up relevant slots, the two sides will simply sit down and negotiate a deal. But valuing a slot is an inexact science because any specific slot will be worth more to one airline than another. For example, airlines with extensive networks are likely to value a slot more highly than a smaller carrier would because of the connecting traffic a slot may also bring in.

The starting point is an assessment of how much revenue that slot (or more precisely, a pair of take–off and landing slots) will generate. In theory, as with any other investment decision, airlines should work out discounted cash flows for the slots they wish to acquire, but in practice airlines use everything from payback periods and internal rates of return (which are both inadequate investment methodologies) to, as one senior executive puts it, “simply sticking your finger in the air and pulling out a value”.

Once slot values have been agreed, differences in the value of two packages of slots are made up via anything from slots at other airports to, most commonly, cash. Once a deal is agreed, the two airlines then approach the relevant airport slot allocator/scheduler (the Airport Co–ordination Limited at London Heathrow) and fill in a form with details of the proposed slot swaps. The cash adjustments/ foreign slots part of the bilateral airline deal is, of course, not notified to the official allocator. And while it may be pretty obvious to an allocator that a proposed slot swap is unbalanced (without a cash adjustment on the side), in practice the swaps are almost always approved. The airlines get the slots they want and cash payments disappear into operating revenue and cost figures.

At present all this goes on in secret as the market is grey and, according to another senior airline executive, “it doesn’t feel right” to admit slot/cash trades publicly.

How much is a slot worth?

As has just been pointed out, a slot’s worth varies according to each airline’s specific circumstances. This makes generic statements about slot values almost impossible — although that doesn’t stop people trying. In the US the General Accounting Office has stated that in 1996 peak–time slots cost an average of $2m at a high density airport (e.g. New York JFK) while off–peak slots cost $0.5m. As an example, this year Continental sold (and then leased–back) 102 slots at Chicago O’Hare, Washington Reagan National and New York LaGuardia for $151m.

In Europe, as the market is grey, accurate details about slot transactions are almost impossible to acquire. In the absence of real data, some figures have to be treated with caution. For example, the rumour that one pair of peaktime slots at Heathrow sold for £600m (The Guardian, London, June 12) can clearly be discounted. At the lower end of the price scale, after BA told the UK’s House of Commons Transport Committee that it had “acquired” 100 slots at Heathrow and 300 at Gatwick from other airlines, analysts “calculated” (i.e. guessed) that BA paid at least £160m ($260m) for them, at an average of £400,000 ($651,000) per slot.

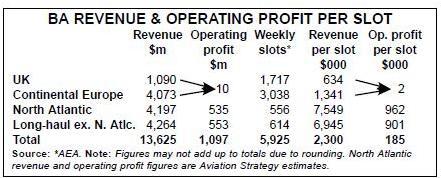

It has been widely reported that the 267 slots that BA has to give up are worth between £1m-£1.9m ($1.6m-$3.1m) each, but even if this range is accurate the value of BA’s slots could vary anywhere between $427m and $828m. In reality BA will only know how much it can get for the slots when potential buyers value the revenue the slots will generate for themselves and make a formal offer. Aviation Strategy calculations (see table, right) show that in 1997 BA’s North Atlantic slots on average earned $7.5m in revenue and $962,000 in operating profits.

Going legitimate

If the Commission does not manage to prevent BA from selling the 267 slots, then the grey market will become a $1 open market.

This can only be to the benefit of the aviation industry in general. Those who argue that an open market will be unfair as only the strongest airlines will be able to afford the highest slot prices are missing the point. In a free market prices should be decided solely by supply and demand. If any airline — new entrant or not — cannot pay the going rate for a slot on the open market then it simply should should not operate on the route. On the other hand, any new entrant that wants specific slots and is properly financed will be able to buy them on an open market, without the lengthy process of having to sculk around on the grey market. If anything, an open market may actually help new entrant airlines as slot prices will be transparent, with less chance that prices are artificially high or that any other abusive behaviour goes on (which if they did occur would be covered by existing anti–predation regulations).

The UK’s CAA is among those calling for the legitimisation of the grey market. In its report “The Single European Aviation Market”, released in June 1998, the CAA says that: “The formal recognition of secondary trading ... would at the very least help maintain and improve the flexibility of the system.”

The CAA adds that while, in its view, an open market is unlikely to lead to more scarce slots being used to promote newly competing services on routes within the EU, this trend has been in evidence for some years at congested hubs anyway, even under the existing slot allocation system. According to the CAA it is important therefore that any changes to the existing system are “judged against existing realities and not against some, possibly unrealisable, ideal”.

That is an important point. It may well be unfair that in an open market a windfall accrues to BA because it was handed a large swathe of slots for free when it was privatised, but that is history (although this could be solved by the UK government being given a percentage of windfall slot gains at BA). What matters now is the need to liquify the supply and demand for scarce slots.

The bottom line is that there is a demand for a proper, open market for slots. This does not preclude the award of new slots through the existing allocation system — in fact there may be a case for the existing allocation systems giving slots to new entrants only, with incumbents only being allowed to gain slots via buying them on the open market.

On the other hand, even in the unlikely event that the UK government is forced to back down and BA has to give its slots away, the question of whether to legitimise the grey market will not go away. That’s simply a function of demand — most airlines want some mechanism whereby slots can be traded quickly and efficiently, and in the face of this need the objections of Karel Van Miert, EU competition commissioner, are futile long–term.

| Revenue | Operating Profit | Weekly Slots | Revenue per slot | Op. profit Per slot | ||

| $m | $m | $000 | $000 | |||

| UK | 1,090 | 10 | 1,717 | 634 | 2 | |

| Continental Europe | 4,073 | 3,038 | 1,341 | |||

| North Atlantic | 4,197 | 535 | 556 | 7,549 | 962 | |

| Long-haul ex. N. Atlc. | 4,264 | 553 | 614 | 6,945 | 901 | |

| Total | 13,625 | 1,097 | 5,925 | 2,300 | 185 | |