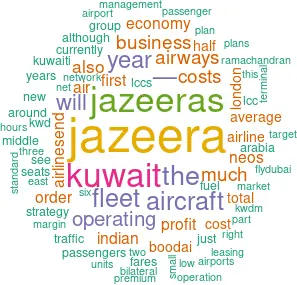

Jazeera Airways:

Small can be beautiful; — September 2019

Jazeera Airways, the Kuwait-based LCC, is remarkable in that it has achieved consistent and very decent margins, and a stock market quotation, while operating a very small fleet of A320s, challenging the assumption that scale is a necessity for operational and financial success.

Jazeera was founded in 2004 by local investors led by the Boodai Group, Kuwait’s leading private conglomerate, with interests in construction, engineering, shipping, logistical services, energy, consumer durables and media (although it is not connected to the Qatar-based Jazeera television service — Jazeera means peninsula, as in Arabian). The Boodai Group currently owns 26% of the airline, 24% by other Kuwaiti companies, with the remaining 50% traded on the Boursa Kuwait. As at the end of September the airline was valued on the stockmarket at KWD194m (US $640m).

……