Delta: will it continue to outperform?

October 2012

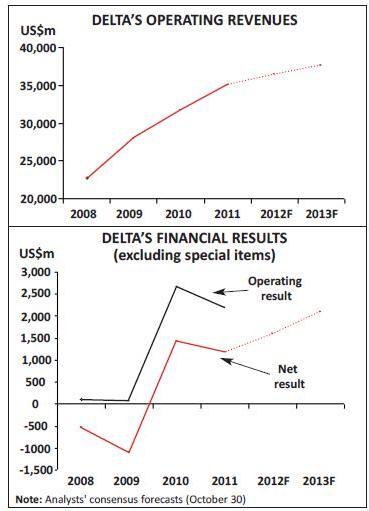

Delta, the second largest US carrier, is on a roll: outperforming its peers in terms of RASM and profit margins, paying down debt, getting into the oil refinery business and snapping up minority equity stakes in Aeromexico and Gol. But will the intriguing new strategies pay off? Can Delta sustain its lead in the longer term when key competitors overcome their current challenges?

Delta is fortunate in that, with the integration following the successful 2008 merger with Northwest long behind it, it has been enjoying a period of relative calm. Unlike the other two of the “US Big Three”, it has no major dramas or risks to deal with.

American is in Chapter 11, trying to reorganise and having serious problems with its pilots. It has lost corporate share in recent months due to extensive flight delays and cancellations – a result of pilot sick calls, maintenance issues and other problems.

United has had terrible merger integration problems this year, resulting from an over-ambitious systems switchover in March. It has alienated business customers and is likely to be the only sizable US carrier to see earnings dip in 2012.

Even Southwest — now Delta’s largest competitor in Atlanta as a result of its acquisition of AirTran — has not been in a position to give Delta a run for its money because it is still in the process of integrating AirTran and combining the two networks. Delta executives noted recently that the Southwest/AirTran combine was “almost 50% down in capacity” from AirTran’s peak in Atlanta and that “they are rationalising more and more cities”. Therefore, while feeling some adverse effects from aggressive fare sales, Delta appears to be temporarily gaining market share also from Southwest.

Of course, Delta’s larger global route

Delta has outperformed its peers in terms of unit revenues for six consecutive quarters. According to BofA Merrill Lynch, its 3% PRASM increase in this year’s third quarter outpaced industry gains by two points.

Delta is earning solid profits and generating significant free cash flow. Its 10.2% ex-item operating margin in the third quarter was among the best in the industry. 2012 will be a third consecutive solidly profitable year for the carrier. As of October 24 (before any impact from Superstorm Sandy), Delta was expected to earn a 6-7% operating margin and a 4-5% ex-item net margin in 2012.

This period of relative calm at Delta has enabled Delta’s management to focus on managing the airline to the best of their abilities. The results have been impressive.

First, Delta has been the industry leader in capacity discipline. Its dramatic 10% capacity reduction on the transatlantic last winter season was instrumental in maintaining healthy RASM growth and profitability in European operations.

Second, Delta is determined to maintain its CASM advantage. On the non-fuel side, it is targeting $1bn of structural cost savings over the next two years. Key measures include a domestic fleet restructuring, which will see a dramatic reduction in 50-seat RJs in favour of operating more cost-effective mainline aircraft and larger RJs.

As part of that programme, Delta recently shut down its regional subsidiary Comair and is currently in talks with

Third, in the spring Delta’s management and pilots negotiated a new contract in a record two months. It is an industry-leading deal but one that gives Delta significant flexibility to restructure its fleet and operations.

It appears to have been a carefully calculated move that also avoids the misery of the kind of protracted difficult labour negotiations that AMR and UAL have been mired in for years (though United did finally secure a new pilot deal in July). Delta is known for its excellent labour relations.

Fourth, Delta has found an interesting potential solution to reducing and limiting volatility in fuel prices: acquiring its own oil refinery. The airline predicts that the Trainer facility in Pennsylvania will save it $300m-plus annually on fuel expenses.

Fifth, in the past year Delta has acquired small equity stakes in Aeromexico and Gol, to strengthen its position in Latin America and to facilitate cost reductions. In August Delta and Aeromexico announced plans to construct a jointly operated MRO facility in Mexico.

Sixth, apart from such strategic (and relatively modest) investments, Delta is exhibiting remarkable capital spending restraint, despite having a relatively old fleet and a much smaller orderbook than its peers.

Seventh, Delta is making great progress in deleveraging its balance sheet. With lease-adjusted net debt amounting to $11.9bn at the end of September, Delta is now on the home stretch in reducing that figure from $17bn at year-end 2009 to $10bn by mid-2013.

2013 is likely to see much discussion on what Delta’s next capital priorities might be after the $10bn debt reduction target is achieved. Will there be further debt reduction? Or will Delta pre-fund pensions, buy back stock or introduce dividends? Or will it be time to start fleet renewal in earnest?

Outperforming in RASM

Delta has enjoyed solid unit revenue growth across all entities in recent months. According to BofA Merrill Lynch, the PRASM outperformance has been the greatest on domestic and transatlantic routes. The analysts predicted that Delta’s PRASM would continue to outpace the sector in 2013, especially in light of its increased corporate share in New York.

One of Delta’s biggest projects this year has been facility improvements and major expansion at New York LGA, following the earlier slot swap with US Airways. Under the highly unusual and brilliant deal, which took years to pass regulatory muster, Delta gained 132 slot pairs at LGA, while US Airways got 42 slot pairs at Reagan National, rights to operate additional daily flights to Sao Paulo from 2015 and $66.5m in cash. The airlines were required to divest 16 slot pairs and LGA and eight at National. The deal involved Delta taking over most of US Airways’ Terminal C at LGA, to create an expanded two-terminal facility at the airport, and spending $100m on renovations and upgrades over two years.

The deal will enable Delta to double its destinations from LGA, significantly strengthening its position in the New York market amid intensified competition (from United Continental, American, JetBlue, Southwest and others). Delta will be creating LGA’s first true connecting hub, with 260-plus daily departures to 60 cities. Given that LGA is New York’s preferred airport for domestic business travel, the positive implications for RASM are obvious.

The early results are highly encouraging. Delta reported in July that it had seen a 2% margin improvement with the initial 18% increase in capacity at LGA. In October Delta executives said that they were pleased that LGA PRASM had remained unchanged in the third quarter despite a 42% capacity increase. The 2012 summer schedule already gave Delta about 50% of daily departures at LGA. The terminal renovations are due to be completed in the current quarter.

With respect to international RASM and future growth, Delta is benefiting, first, from the new $1.4bn state-of-the-art international terminal that opened at its Atlanta home base in May 2012. Second, after long been handicapped by its ageing JFK terminal (T3), Delta, which is the leading US carrier on the transatlantic, will be able to move its international operations to a redeveloped and expanded T4 in the spring of 2013. This first phase of a five-year $1.4bn project will give Delta nine new international gates, a passenger connector between T4 and T2 (which Delta will retain for domestic operations) and expanded baggage claim and customs areas. The many benefits to customers will include faster transit times and one of the largest Sky Club lounges in the Delta system.

With the help of its JV and SkyTeam partners, Delta has been aggressive in culling poorly performing transatlantic flights over the past year. It has reaped major benefits from that strategy. The 10% ASM reduction in late 2011 led to double-digit PRASM growth through the winter season, despite Europe’s economic weakness. The 5% ASM reduction in this year’s September quarter led to a 3% PRASM increase, despite an adverse economic outlook and a weak Euro, and contrasting with the industry’s 0.7% PRASM decline on the transatlantic (according to BofA ML). Somewhat curiously, Delta has benefited from a strong European point of sale; its executives theorised that “European multinationals which are having trouble doing business in Europe are coming to the US to do business”.

Even though the transpacific was Delta’s best-performing entity in the third quarter, the 6% PRASM increase there lagged the sector by three points. Delta’s formidable Japan franchise is profitable but has seen increased competition, and the airline is somewhat handicapped for not having a partner in Japan. Delta has dropped its new Detroit-Haneda route and is seeking to transfer those slots to Seattle, where it has been building transpacific operations with the help of its partner Alaska Airlines.

In addition to gaining new corporate contracts and attracting more business traffic generally, Delta is getting good results from premium up-sell programmes and other revenue initiatives. The past two years’ product improvements have included a new “Economy Comfort” section on aircraft, increased first-class seating domestically, interior upgrades, WiFi, full flat-bed seats in the Business Elite cabins and FFP enhancements.

Analysts made the point in Delta’s 3Q call that the airline may have to give up some of the recently-gained corporate share after a reorganised AMR emerges from Chapter 11 next year, possibly strengthened by a merger. That may happen, though Delta executives felt that most of the gains have been “truly new share” resulting from Delta’s own efforts and that the gains from American have not been significant.

Like other US airlines, Delta is in favour of further industry consolidation, including a potential merger involving AMR, because it would help maintain industry capacity discipline and a rational pricing environment. Of course, as CEO Anderson put it, Delta believes that it has “competitive advantages that will allow us to continue to sustain the distance that we put between ourselves and the rest of the industry”.

Cost cutting imperative

Because Delta and Northwest restructured in Chapter 11 relatively recently (both emerged in the spring of 2007), the airline that resulted from the October 2008 merger has enjoyed a cost advantage over its peers. However, the CASM advantage has narrowed in the past couple of years due to pay increases to integrate labour, product and service upgrades, the ageing fleet and the capacity cuts. Delta’s system capacity is slated to fall by 3-4% this year, after a 0.2% decline in 2011. In the third quarter, Delta’s non-fuel CASM rose by 5.6% — more than double the industry increase. The airline warned that cost pressures would continue into the first half of 2013.

This year Delta has been talking about a new $1bn programme of structural cost initiatives aimed at generating savings from the second half of 2013. The measures aim to offset cost inflation in other parts of the business and produce “comprehensive structural changes” to the way Delta does business.

The biggest part is a domestic fleet restructuring, though the programme will also aim to achieve maintenance savings and technology and process-driven efficiencies. Having already completely retired its turboprop fleet, Delta now intends to replace 75% of it 50-seat flying with more cost-effective mainline aircraft – “capital-efficient” 717s and MD-90s and new 737-900s — and by larger (two-class) RJs. The 50-seat RJ fleet operated by regional partners will shrink from a peak of more than 500 in 2008 to fewer than 125.

Under a deal negotiated in May and which was conditional on the pilot deal being ratified, Delta is subleasing all 88 of the 717s Southwest inherited as part of its acquisition of AirTran (solving a major problem for Southwest, which prefers to operate only 737s). 78 of the aircraft are on lease from Boeing Capital while ten are owned. The aircraft will be delivered to Delta over three years, at a rate of about three aircraft per month, starting in mid-2013.

Like many other airlines, Delta has found that at current fuel prices the 50-seat RJs are no longer economic, particularly on stage lengths of over 450 miles. The aircraft were also becoming more expensive to maintain. By deploying larger aircraft in those markets Delta will be able to both achieve significant maintenance and operating cost savings and improve the onboard experience for passengers.

This strategy meant the closure of Cincinnati-based Comair at the end of September – one of few remaining wholly owned commuter units in the US. Delta had already drastically shrunk Comair over two years, after failing to find a buyer. When the closure decision was announced in July, Comair operated only 44 aircraft, accounting for 1% of Delta’s network capacity.

Delta is currently evaluating larger regional jet models offered by Bombardier and Embraer and expects to make that decision, as well as the decision on who will operate and own the aircraft, by year-end. The new pilot deal permits up to 70 additional 76-seat RJs on top of the 255 already deployed in Delta’s regional operations.

The new pilot deal, which was ratified at the end of June, was instrumental in making all of that restructuring possible. Delta also secured productivity improvements, more flexible work rules and lower profit sharing. But the deal will be expensive for the airline, because the pilots secured pay increases totalling almost 20% by the end of 2014.

It was an industry-leading contract, with potential ramifications for pilot pay and negotiations at other US carriers. (It immediately paved the way for a new pilot deal at United, which the union described as being “on par with Delta from a pay-rate perspective”, but appears not to have helped things at all at American.)

When asked in the 3Q call how Delta can afford the new pilot contract, CEO Anderson spoke of the “overall value” that will be created. He expressed confidence that the deal will help Delta attain the unit cost levels it needs over the next couple of years to improve margins and ROIC.

Delta will not be releasing 2H13 cost guidance or any specific CASM targets until its investor day in December, when the timing of the various structural initiatives will be clearer. However, the financial community’s response especially to the fleet restructuring has been highly positive.

The oil refinery venture

Then there will be the potential fuel cost savings from the Trainer refinery complex, which Delta continues to project at around $300m annually at full run rate.

Delta surprised many and attracted criticism for its bold and unusual move in the spring to acquire the idled oil refinery south of Philadelphia, aimed at managing its largest expense. Sceptics argued that the move was too risky and an unnecessary diversion for an airline. But since then attitudes have changed, especially since the economics look highly attractive.

In June Fitch Ratings called it an “innovative approach to the long-term management of the airline’s jet fuel costs, notwithstanding the operational risks of running a refinery”. The agency noted that fuel accounted 36% of Delta’s operating expenses in 2011 and that the crack spread alone represented 10% of unit costs, up from 3% two years ago, “highlighting the urgency of alternative approaches to jet fuel cost management”. While potential risks included “ongoing capex requirements, changes in the regulatory environment and operational issues linked to potential refinery outages in a single-asset business”, Fitch considered that Trainer could give Delta “at least a 10 cent per gallon advantage over its competitors, as it cuts out the middleman and his profits”.

Delta bought the Trainer facility from Conoco’s Phillips 66 through wholly-owned subsidiary Monroe Energy. It entered into strategic sourcing and marketing agreements with BP and Phillips 66 and put in place a “seasoned leadership team headed by 25-year refinery veteran Jeffrey Warmann”. BP will supply crude oil to be refined at the facility, and Monroe Energy will exchange gasoline and other refined products from Trainer for jet fuel from Phillips 66 and BP. The acquisition included pipelines and transportation assets that will provide access to the delivery network for jet fuel reaching Delta’s operations throughout the Northeast, including LGA and JFK. The facility will provide 80% of Delta’s jet fuel needs in the US .

The acquisition cost to Delta was $150m (after $30m state government assistance for job creation and suchlike). After investing another $100m on renovations and upgrades, Delta restarted Trainer’s operations in September and expects to be at full production (refining 185,000 barrels per day) by 1Q13. The facility is expected to make a positive contribution of up to $25m to Delta’s earnings in the current quarter.

Assuming the $300m annual savings (off Delta’s $12bn fuel bill), which looks like a conservative estimate in light of the higher than normal jet fuel crack spreads this autumn, Delta would fully recover its $250m investment in year one.

So at this point it looks like a commendable effort to control fuel costs. Delta is the first airline to make its own fuel, though others have talked about it. United reportedly recently briefly looked at investing in a Texas refinery but decided that it had better uses for the $100m, such as paying down debt or investing in the product.

Interesting alliance moves

In addition to the continued development of the JV with Air France-KLM and Alitalia, which is probably the most deeply integrated of the transatlantic JVs, and efforts to recruit new SkyTeam members and develop cooperation with existing members, in August 2011 Delta forged a very interesting deeper “long-term exclusive commercial alliance” with its SkyTeam partner Aeromexico. The deal, which was approved by Mexico’s competition commission this summer (and which may actually have started a trend of global alliance members pairing up to forge deeper links), has meant Delta investing $65m for a 4.2% stake in Aeromexico and a seat on its board. In August Delta and Aeromexico disclosed more details of their plans to expand their MRO agreement by investing some $50m to build a joint heavy maintenance facility in Mexico. Delta executives commented that the project would “usher in lower maintenance costs” without compromising quality.

In December 2011 Delta invested $100m for a 3% stake in Gol; the deal also gave it a board seat, an exclusive codesharing agreement and two 767s. It was an important strategic move, helping ensure that Delta has a partner in Latin America’s largest domestic market.

There has been speculation on whether Gol might join SkyTeam. With global alliances in a flux and Brazil becoming a key battlefield, CAPA recently reported that SkyTeam, in particular, is trying to develop new “hybrid” membership categories to make it easier and more attractive for LCCs like Gol to join. However, LCCs like Gol and JetBlue have made it very clear that they really do not want to join global alliances, not just because of the cost and restrictions but because they do not need the feed in some distant corner of the globe.

Delta executives have commented in the past that they saw the Aeromexico relationship eventually developing into a JV with ATI, once an open skies regime is secured. They also suggested that it might be a template for other relationships “particularly in South America”. Given that there is also a trend away from “loose global alliances toward deeper pacts between individual airlines” (as the Wall Street Journal described it), that could well be where the Delta-Gol relationship is headed. Another new partner for Delta to focus on in South America is Aerolineas Argentinas, which joined SkyTeam in August.

The Wall Street Journal reported in October that Delta is in talks with SkyTeam partner Korean Air to expand their decade-old commercial alliance, but it is unclear how that could significantly help the carrier in the key transpacific markets.

Financial considerations

With three years of solid profits and significant free cash flow (FCF), and with the debt reduction target likely to be achieved in 2013, Delta is financially the best positioned of the US legacy carriers. It is beginning to focus on long-term margin expansion and shareholder returns. CEO Anderson stated: “We must and will expand out margins and hit our ROIC target of 10-12% on a consistent basis over the next several years”.

Delta’s financial achievements have been recognised by the credit rating agencies this year. In May S&P revised Delta’s outlook to “positive”, hinting that the ratings were likely to improve as the airline repays debt. In June Fitch upgraded Delta from “B-minus” to “B-plus”, citing “two and a half years of strong FCF generation that has translated into a significant debt reduction”.

However, the rating agencies expressed some concern about Delta’s still-sizable debt maturities over the next several years and its massive pension deficit, which exists because only the pilots’ pension plan was terminated in bankruptcy (the other plans were merely frozen). The other legacies terminated all of their pension plans in Chapter 11 (though not AMR), so Delta has a competitive disadvantage. Fitch commented that the mere 40% funded status of the frozen defined-benefit plans is a level that will be “difficult to sustain for an extended period”, though it is obviously not a serious concern as long as Delta’s FCF remains strong.