Hybrid business models

October 2012

We all like to classify data into neat pigeon-holes; in the airline industry as any other. Here we seem to like to think that we have clear definitions of business models: the Low Cost Carrier, the charter operator, the full service “legacy” network carrier. Each is seen to represent a valid business model, with varying levels of pejorative overtones depending on who is speaking. However, it appears that the differentiation is starting to lose clarity, with many carriers starting to take on attributes of others' business models. This has been termed as a move to hybridisation.

When Europe started its initial faltering steps towards airline deregulation a quarter of a century ago, there had been one favoured theory of future development. This suggested that the charter carriers (who then accounted for half the intra European traffic) would move into scheduled and business oriented routes to provide new competition to the flag carriers; the network flag carriers would be forced into lowering costs to meet the new competition while battling it out to create pan-European networks; and that there might have been room for new entrants at the bottom.

In the end it did not work out quite as this theory suggested. The charter operators on the whole (after Air Europe tried and failed) remained wedded to their assumed captive tour operator markets — the only one in the end to have transferred successfully into scheduled operations being Air Berlin. Almost all the impetus of new competition was provided by new entrants — led by Ryanair and easyJet — and from the beginning of the 2000s developing pan-European presence with bases spread through the major countries. The legacy flag carriers have indeed been forced to change, through cost cutting and consolidation, but with concentration on the power of the long-haul network hubs. None of these have been able (nor perhaps has wanted) to develop a pan-European presence — and attempts to establish bases of operations outside their home countries (whether BA trying with DBA, SAS with Spanair, KLM with Air Littoral or latterly Lufthansa with LH Italia) have failed miserably.

The beauty of the Low Cost model is its simplicity (adhering to the “Keep It Simple Stupid” or KISS principle of pioneer Southwest):

- High seating density

- High aircraft utilisation

- Single aircraft type

- Low fares including exceptionally low promotional fares

- Single class configuration

- Point-to-point services

- No (free) frills

- Short-/medium-haul services

- Frequent use of secondary/tertiary airports

- Quick turnaround

Ryanair took the model to a new level:

- Fly to airports which want your services and charge less (or pay you)

- Minimise all controllable costs and make as many costs variable as possible

- Charge fares to maximise load factor

- Internet-only booking

- All “optional” services unbundled from the fare and charged separately.

All this on the basis that air transport is a commodity and that in a commodity market the lowest cost provider will win. In one sense the extreme low cost model works on the basis of providing the capacity to fit in with operational considerations, assuming that the traffic will come at a price that makes commercial sense, or the route will be closed.

In contrast some of the problems of the legacy network model relate to its very complexity. Few long-haul routes make sense on pure real O&D traffic terms and the network model requires a combination of short- and long-haul flights to provide feed in order to maximise potential demand. This requires a coordination between the disparate long- and short-haul route networks, fleet types, and significant additional handling costs to cope with transfer passengers and bags. Implicitly, for historical reasons, transfer could also use the deepest discounts against tariffs limiting the availability for marginal pricing on point to point demand, while also for historical reasons all services were deemed to be included in the ticket price. In one sense the legacy model may also be said to provide its services on the basis of an estimation of what the customer actually wants.

The hybrid model

Increasingly the new entrant LCCs have been trying to find a sense of differentiation — leading to the “hybrid” model (see table, page 1). One of the first elements of this is to eye the potential of yield uplift by providing a service targeted at “business” passengers. This leads to a traditional view of having to offer a minimum morning and evening rotation to each destination (with a mid-day infill) to be attractive — while the origin and destination airports need to be relatively mainstream for business needs. In addition, there is a requirement to have a presence in the global distribution systems (to gain access to corporate bookings and travel agent distribution), and create a marketing team to develop relationships with corporate accounts. All this of course adds to complexity and cost.

Another brilliant idea is to add the concept of providing network connectivity. Each of the large LCCs operate services at their bases which potentially could provide intra-line connections; but the last thing they want is to allocate cost to their operations by guaranteeing that a passenger and her luggage will achieve that connection (or indeed providing compensation if that connection is missed). Where connecting services are offered it is either left to the individual passenger to organise herself or a charge is generated; but unlike the legacy model there is generally no attempt to guarantee minimum connecting times. Inter-line connections on the other hand start to get much more complicated. These require GDS involvement, formal relationships with other carriers, FFP and loyalty programme coordination.

Once you commit to the idea that you need to attract corporate business accounts you start to get the idea that you need to retain them through some form of loyalty programme — if only because the legacy competitors do. Most of the European LCCs have created an opt-in charged-for programme with defined benefits. Some have even been offering uncharged-for frills for those willing to pay higher “flexible” fares, effectively providing an on-board class differentiation in a single class cabin (see table, above).

Some of these aspects of the departure from the KISS principle have limited or no impact on costs. These we might describe as “soft” complexities and may include items such as paid for special seat assignment, full-plane seat allocation, priority boarding, branded credit cards — all of which can be either cost neutral or self financing.

Others — which we might call “hard” complexities — are those items that impose a cost penalty against best in class if not absolutely; and here the operator’s hope is that there will be a sufficient improvement in yield to offset the effective increase in costs required to provide or use the service. These will include the use of primary airports, different aircraft types/sizes, access to global distribution services, provision of intra-line (or transfer) services, frequent flyer or loyalty plans, inter-line or code share agreements, membership of global branded alliances, class differentiation, and operation of long-haul services.

Quantifying the real net benefit of this hybrid model is not easy. Various inconclusive studies have been conducted in the US market just taking increased distribution and sales costs as one element of the change from a pure low cost model, and trying to find a resulting improvement in margins in later reporting periods (although these are possibly tainted as having been authored for the distribution systems themselves). The long term net benefit if any should be seen in the airline’s operating margins; but there are many elements outside the control of the carrier that can affect any one year’s returns.

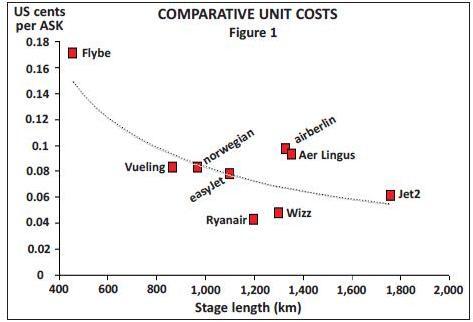

In Figure 1 (page 3) we show a chart of the unit costs of the main European LCCs against average seat stage length. As usual there is an inverse logarithmic relationship between average stage length and achieved unit cost. Ryanair and Wizz — the only two in this sample that remain true to the “pure” KISS principle — lie well below the curve; Flybe (with its regional aircraft types and very short sector lengths) not surprisingly is well off to the top left; the hybrid carriers easyJet, norwegian and Vueling sit bunched fairly close together (with both Vueling and norwegian seemingly showing an effective unit cost advantage against easyJet); while airberlin and Aer Lingus — both with long-haul services and more remnants of their legacy histories — appear significantly out on a limb.

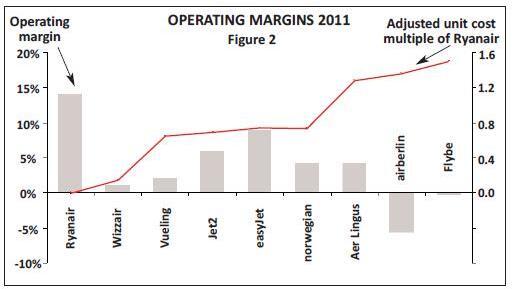

In Figure 2 (above) we show a chart of the 2011 operating margins for the same carriers. We have adjusted unit costs to account for differences in stage length in order to compare with the sector paragon Ryanair; the line represents the stage length adjusted unit costs as a multiple of Ryanair’s. The main conclusion from this chart is that the two largest LCCs (Ryanair and easyJet) have the largest margins; and that perhaps easyJet’s departures from the KISS principle have reduced its ability to generate margins a little.

| Ryanair | Wizzair | easyJet | norwegian | airBerlin | Vueling | flybe | Aer Lingus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Complexities | Pure KISS | X | X | ||||||

| Secondary/tertiary airports | X | X | X | ||||||

| Single aircraft type | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Primary / congested airports | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Corporate accounts | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| GDS/Travel Agent distribution | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Transfer traffic | X | X | X | X | |||||

| FFP | X | X | X | ||||||

| Code share | X | X | X | X | |||||

| GBA (Global Branded Alliance) | X | ||||||||

| Class/Seat differentiation | X | X | X | ||||||

| Long haul | X | X | X | ||||||

| Soft Complexities | Loyalty card (paid for) | X | X | X | |||||

| Special seat allocation (paid for) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Full plane seat allocation | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Priority boarding | X | ||||||||

| Credit card | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Family discount | X | ||||||||

| In house bank | X |