Ryanair's hollow threat to cancel orders and shrink?

October 2009

Like other airlines, Ryanair has been hit hard by the global recession, although not as severely as many other carriers. Surprisingly, however, the LCC is now threatening to cancel orders and purposely manage its decline into a “cash cow”. Is this a serious option, or is the world’s largest LCC playing a dangerous game of brinkmanship with Boeing?

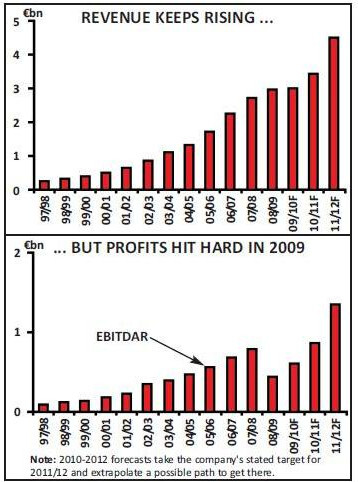

At the beginning of October Michael O'Leary, Ryanair’s CEO, started off proceedings at the airline’s annual investor day by saying that the bad news was that there was no new good news, but that the good news was that there was no new bad news. He reiterated the company earnings' guidance of doubling underlying profits to the lower end of a range of €200m-€300m for the year to the end of March 2010 – albeit from the very low level of the last financial year (and ignoring the €218m accelerated depreciation and mark–to market of the Aer Lingus stake, which pushed the company into a published net loss of €169m).

A public “bust-up”...

O’Leary also reinforced the company’s aim to double passenger numbers and profits over the five years to the end of March 2012 – targeting total annual passenger numbers in that year of more than 80m (against a current 12 month rolling figure of 67m) and profits of more than €800m. Having said all this, he then warned investors that the company was encountering some problems in its attempts to negotiate the next batch of 737 orders for delivery from 2013. O’Leary had been hoping to better the extraordinary deal he made in the last downturn, but he now implied that there was a very real possibility of a public “bust up” with the Seattle manufacturer. In light of this, he then suggested that if an agreement could not be reached he might cancel remaining orders and options and rein back growth significantly from 2011, instead running the airline “for cash”.

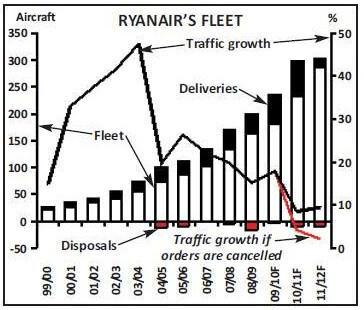

Ryanair currently has a fleet of 202 737- 800 aircraft, with an average age of just under three years. It has orders in place for a further 110 aircraft and 102 options for delivery up to 2012 (see chart, below); the next 59 aircraft due to be delivered by October 2010 have already been fully financed, all but four (to be taken on operating lease) financed through Exim Bank facilities. As plans stand at the moment, it has a further 51 aircraft for delivery between October 2010 and March 2012 still to be financed; and the plans are predicated on continuing to push an increase of capacity of around 10% a year into the market. Part of the rationale of the Ryanair fleet plan has been to dispose of some of the older equipment – acquired at higher initial costs and lower €/US$ exchange rates – to minimise ownership costs and therefore the unit costs of operation.

Ryanair currently operates from 36 bases throughout the EU, with more than 1,300 daily flights on 900 routes between 151 airports. This gives it the largest coverage of Europe of any European airline (albeit not with meaningful frequency on many routes). It can boast that it is the second largest passenger carrier within and into/out of the UK, Italy, Spain and Belgium, with market shares of between 12% and 19%, and the third–largest in France and Germany, with market shares of 7–8% (see table, right). It is of course the largest carrier in Eire, with a near 50% share of the market.

Ryanair is proud to claim the accolade of providing the lowest average fare in Europe, at €37 one–way, or some 13% below the average fare of easyJet, its nearest competitor. It also boasts the best customer service, in that it has the best punctuality, reliability, the fewest misplaced bags (it does help not to operate a hub sometimes, and apparently Ryanair fines its airports and handlers for mishandled bags) as well as the fewest cancellations (see table, page 18).

If Ryanair does slam on the brakes to its growth path it could start to become even more indecently profitable. One of the prime tenets of the Ryanair business plan is to operate “load factor active, yield passive”. Indeed it is one of the basic principles in air transport economics that the more capacity you put into the market the more you have to encourage traffic, and with high rates of growth the introduction of marginal new routes and marginal capacity on existing routes can act as a dilution to pricing power and achieving high yields.

By stopping growth – or at least minimising it towards the “natural” growth characteristics of the market – Ryanair would be able to achieve strong yield improvements. As the lowest cost provider in what is essentially a commodity market it would still remain exceedingly competitive, while its very low cost base ensures that it will still be able to operate routes totally uneconomic to other airlines.

Even more cash ...

It will, however, probably find it more difficult to achieve unit operating cost savings (its operating costs per passenger excluding fuel are expected to have fallen by 5% year–on–year in the current financial year ending March 2010, and have fallen by 42% since 2000); particularly since as the fleet ages it will start to encounter operational delays as well as increasing maintenance costs. To achieve those cost savings it is likely to intensify its negotiations with suppliers even more and concentrate on the low cost options. Financially, if it stops growth plans completely it is therefore likely to find cash pouring out of its ears: with some €250m annual depreciation and in the absence of its €1bn annual aircraft capex, cash balances even at break–even profitability could continue to grow at well over €1bn a year (or some 30% of revenues). At the end of June it had €2.5bn in cash on its balance sheet (an enviable 85% of annual revenues) while net debt stood at €105m, without taking account of the €400m cash tied up in its 29% stake in Aer Lingus (written down to €80m on the balance sheet and currently worth €113m).

In addition there is a substantial amount of cash included in the fixed asset schedule as deposits for future aircraft deliveries –more than €400m at the end of March 2009. Not entirely jokingly perhaps, and no doubt in light of the current political arguments against bankers' pay scales and bonuses, O'Leary suggested that management would first put in place a really good management bonus scheme before paying surplus cash to shareholders as “special” dividends (although of course he is also a major shareholder).

On the other hand, this threat has potential downsides. The company has so far successfully avoided attempts at forced union recognition, and particularly pilot union recognition. In part, it claims, this is because it offers pilots a highly attractive package: no “overnights”; no “through the nights”; no time zone problems; fixed and predictable roster patterns; guaranteed one month’s annual leave plus two lots of 13 day breaks – with pilots therefore sleeping in their own beds each night.

In addition, some 50% of all its pilots (and also the cabin crew) are on a contract basis – paid by the hour – providing a substantial flexibility in seasonal rostering. Indeed BALPA tried to force recognition for Ryanair’s UK pilots this year, but backed down apparently through lack of necessary support. In the past year the company has been at pains to negotiate long–term four–year pay contracts with pilots at each of its bases, and at the investor day was able to boast that it had achieved this throughout the network.

It is important that Ryanair’s pilots are employed on the more flexible (for the employer) UK or Eire employment contracts – although there are no doubt dangers that the French in particular (and other EU countries perhaps too) will try to enforce local country contract requirements, and perhaps require union recognition. It appears fairly clear that faced with such an imposition Ryanair would close down operations in such bases affected.

A chance for Airbus?

However, should Ryanair be seen to be making significant profits and distributing the returns to shareholders, it appears entirely possible that it may encounter increasing belligerence from the pilot workforce for a share of the pot. It is, however, very unlikely that the Ryanair management have not considered the implications. Having said all this, a break–down in negotiations with Boeing could well open up the possibility of real negotiations with Airbus – which up to now may have felt its negotiating position was hopeless (and which apparently earlier this year declined to participate in talks with Ryanair on the basis that the discount to list prices being requested was far too high) – and pave the way for Ryanair to start building an Airbus fleet and possibly put it in an even better position for future negotiations with the aircraft manufacturing duopoly.

This could suggest that public statements of an abandonment of growth plans will be short–lived (and if it had been able to acquire Aer Lingus, with its Airbus fleet, it would already perhaps be in that position). There is therefore the possibility that a potential public break up with Seattle realistically allows Ryanair to acquire the low cost lift to generate the growth it feels it needs from Toulouse. Given Ryanair’s increasing market presence it seems unlikely that either manufacturer would regard this as ideal, although in the end both will want to secure orders even in the downturn, and will have to put a price on an order for up to 400 new aircraft from one of the few airlines that has the ability to pay – but only a price acceptable to Ryanair.

This approach to negotiations seems to permeate the ethos at the company.Earlier this year, Ryanair closed down most of its routes (except for the lucrative one to Dublin — the fourth most important route in its network) from Manchester, seemingly because it did not like the airport imposing increases in charges. It was happy to secede to easyJet the higher yielding (but high cost) routes out of that airport (e.g. to Spain) in favour of routes from airports that would offer lower costs and hopefully longer term deals.

Airport anger

Similarly, it had tried to negotiate with Milan’s Malpensa airport last year to gain a long–term charging formula, but walked away – to retain its base at Orio al Serio – allowing easyJet (and to a lesser extent Lufthansa) to move into the Milanese airport as a replacement for the retrenching Alitalia. O'Leary commented in one of the sessions at the investor day that he was quite happy to wait until easyJet’s growth out of Milan slowed and SEA decided that it needed another source of growth, and then would return to the negotiating table – but only on his terms. Apparently in these difficult economic times, other “major” airports have initiated talks with Ryanair to attempt to persuade it to set up a base (other airline failures are helping this trend) and Ryanair stated that it had enough airport opportunities to build towards carrying more than 100m passengers a year. Meanwhile, the company has been very vociferous publicly over the operations and charges at its two largest bases, at London Stansted and Dublin, and very publicly critical of the expansion plans at both (and the regulators' acquiescence in allowing landing charges to rise to pay for them). In London, (BAA’s appeal notwithstanding), Ryanair appears to have won a prime negotiating position after the competition authorities in the UK declared a requirement for BAA to sell London’s third airport. However, whoever looks to acquire the airport from the Ferrovial consortium will have to negotiate with Ryanair; and the airline would be able to promise growth of services and guarantees of income — but only on its own terms and with exceedingly low landing charges.

In Dublin meanwhile, it appears that other airlines (also at the moment incidentally suffering badly from the recession) are starting to raise real concerns about the need to operate the new terminal – or more specifically to pay for it – while Aer Lingus, itself in a desperate financial state, can hardly be looking forward to substantial increases in costs at its home base. Meanwhile, partly as a result of the deep recession in both countries, and partly because of the UK APD and the Irish tourist tax, Ryanair has announced deep cuts in winter capacity at both airports (although not as deep a set of cuts as the public releases may suggest).

At the same time, Ryanair has imposed internet–only check–in – and, in a manner of what many may see as hubris, is imposing a €5/£5 charge for doing so (and a penalty of €40 for failure to do so). This may take the idea of unbundling fares to an unwarranted extreme (and indeed may backfire, although O’Leary talks of “educating and disciplining the passenger”), but removes the need for the use of check–in desks (for which the airline gets charged at the airport) and incidentally frees up some elements of terminal capacity for the airports concerned, making — from Ryanair’s point of view — their arguments for terminal expansion specious.

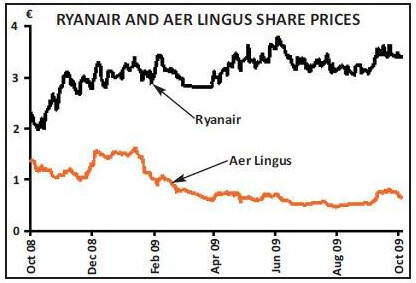

Ryanair is also sitting on an unproductive 29% stake in Aer Lingus: full takeover uniquely blocked (no doubt at the Irish government’s request) by Brussels. It appears very unlikely now that Ryanair will initiate a third public bid for its local rival; but it may very well be willing to sit and wait. The Irish “flag” carrier is suffering more than most in this downturn – mainly because it is having to compete head–on with Ryanair. It has recently announced another major restructuring plan to cut costs by nearly €100m by 2011 (around 12% of non–fuel costs) – with a major redundancy plan, deferral of aircraft deliveries, and reassessment of pension provisions – which may just produce returns before its cash balances (€1bn gross cash at the end of June, net cash €440m down from €800m a year earlier) become uncomfortable.

Unfortunately, having slimmed down its operations so far in its restructuring in the early 2000s, it may have little real further opportunity to dream of approaching Ryanair’s cost base – even by moving operations to London Gatwick. Aer Lingus does not necessarily have the leeway to raise the much–needed cash that was enjoyed by BA, Lufthansa or Air France earlier this year, or the major US carriers recently – unless it were able to persuade the Irish Government to allow it to sell its valuable slots at London Heathrow. Any attempt to raise cash from shareholders would probably require Ryanair’s agreement, while the government and the employee pension funds may find a request to put up funds uncomfortable.

O'Leary appears quite happy to wait for the humiliating call to rescue Aer Lingus – and his recent comments suggesting using it as a vehicle to bid for bmi may not be too far off the wall, and could allow Ryanair legitimate access into the more mainstream airports.

The airline industry is quite good at generating high profile maverick players, and working out quite where a maverick will next jump is almost impossible. Ryanair’s mantra to double passengers, revenues and profits between 2007 and 2012 may not quite yet be believed by the financial markets, but under current plans could be achieved (after the declines of last year and this) by a 5% annual growth in revenues per passenger over the next two years – to bring it back to the €52/pax generated in 2007.

If it does have a breakdown in negotiations with Boeing and cuts back its growth plans significantly, it may have to generate an annual growth in revenues per passenger of more than 10%. However, by following a low or static growth path from 2012 onwards this may ironically give it an additional cost advantage over other LCCs – among other things in not having to buy quite so many emissions allowances as the aviation industry enters the European Emissions Trading Scheme as would otherwise be the case – but would create more problems in the longer term over how to deal with an ageing fleet.

Meanwhile, in deciding where Ryanair goes from here, O’Leary may just be faced with an embarrassing number of strategic options for Ryanair.

| International | |||||||

| & domestic | Market | Market | |||||

| capacity | |||||||

| UK | (m seats) | share | rank | ||||

| 1.9 | 17% | 2 | |||||

| Italy | 1.3 | 16% | 2 | ||||

| Ireland | 0.7 | 49% | 1 | ||||

| Spain | 1.3 | 12% | 2 | ||||

| Belgium | 0.2 | 19% | 2 | ||||

| France | 0.5 | 8% | 3 | ||||

| Germany | 0.7 | 7% | 3 | ||||

| Source: Ryanair. | |||||||

| Missed bags | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| per 1,000 | |||

| Punctuality | pax | Reliability | |

| Ryanair | 93.0% | 0.4 | 99.6% |

| Luxair | 90.3% | 7.6 | 85.4% |

| KLM | 89.9% | 14.4 | 98.6% |

| Austrian | 89.3% | 10.1 | 99.4% |

| LOT | 87.9% | 9.8 | 97.7% |

| bmi | 86.5% | 17.2 | 98.5% |

| SAS | 86.4% | 9.1 | 99.0% |

| Tarom | 85.7% | 9.8 | 99.2% |

| Finnair | 85.2% | 11.4 | 99.5% |

| TAP | 85.0% | 17.3 | 99.2% |

| Lufthansa | 84.7% | 10.9 | 98.4% |

| Brussels | 84.9% | 9.1 | 98.6% |

| Icelandair | 84.3% | 7.6 | 100.0% |

| AeroSvit | 84.1% | 5.2 | 99.2% |

| Adria Airways | 83.7% | 7.0 | 99.7% |

| swiss | 83.4% | 9.0 | 98.5% |

| Air France | 83.3% | 18.9 | 97.0% |

| Malev | 82.9% | 8.6 | 97.7% |

| BA | 82.6% | 15.6 | 98.0% |

| CSA Czech Airlines | 81.1% | 9.1 | 99.0% |

| Croatia Airlines | 81.1% | 7.7 | 97.5% |

| Air Malta | 80.3% | 4.6 | 99.8% |

| Olympic Airlines | 80.0% | n.a. | 96.7% |

| JAT Airways | 76.3% | n.a. | 98.0% |

| Alitalia | 73.8% | 19.6 | 98.8% |

| THY | 70.4% | 4.5 | n.a. |

| Iberia | 70.2% | 19.2 | 97.0% |

| Cyprus Airways | 69.3% | 8.0 | 99.4% |