Aeroflot: ready for life without Siberian fees?

October 2009

Under a new CEO, Aeroflot is preparing for the loss of Siberian overflight fees through fleet modernisation, a large reduction in its workforce and the restructuring of loss–making subsidiaries. But can Russia’s flag carrier succeed in preparing itself for an era without substantial indirect state subsidies?

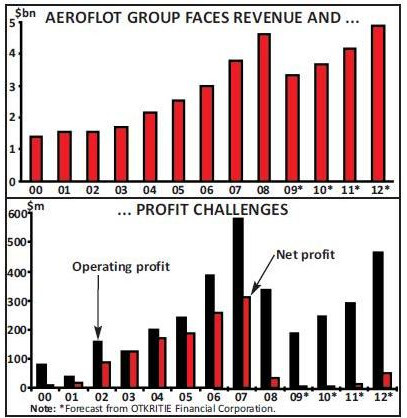

At first sight Aeroflot — which operates to almost 100 destinations around the world — appears to be one of Europe’s most profitable airlines, with rising revenue and profits through the 2000s until last year (see chart, right). And even in 2008 it still managed to achieve a substantial operating profit equivalent to $339m, though this was 41.3% down on 2007.

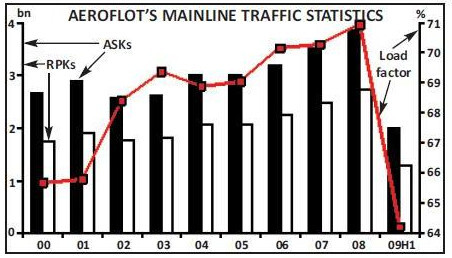

Indeed the Aeroflot group carried 11.6m passengers in 2008, 13.7% up year–on–year, with the mainline carrying 9.3m passengers, 13.5% up on 2007 (at a load factor of 70.9%, 0.6 percentage points up on 2007), of which 5.7m were international passengers.

However, the full–year results for 2008 (not released until July this year) also reveal deep underlying problems at the airline. While revenue reached $4.6bn — 21.2% up on 2007 — costs rose at a faster rate (with fuel costs rising 51% to $1.5bn), leading to the fall in operating profit, while net profits plunged to $37m, compared with $313m a year earlier.

And it’s this net figure that is particularly worrying, since it reflected: ongoing losses at Aeroflot’s three main subsidiaries — Aeroflot–Cargo (which recorded a $105.3m loss in 2008), Aeroflot–Nord ($25m) and Aeroflot–Don ($32.3m) — as well as at other subsidiaries ($62m), the rise in fuel prices, foreign exchange losses and losses associated with a revaluation in US$ of loans for the new terminal at Sheremetyevo ($45.5m) due to the depreciation of the Russian rouble.

End to the windfall

Crucially, 2008’s poor net result was achieved despite the huge boost given traditionally by fees paid by European airlines overflying Siberia on long–haul routes to the Asia–Pacific region (which are on top of standard air navigation charges). A legacy of the former Soviet Union, these fees are handed straight to Aeroflot (although the airline does then have to pay various taxes and charges to the Russian aviation authorities from this pot of money). This huge windfall has underpinned Aeroflot’s results for decades, but an agreement between the European Union and Russia means that these overflight fees will be completely abolished by the end of 2013. Other Russian airlines have also lobbied to share in these royalties, but it is understood that a deal has been done with the government that ensures that Aeroflot will continue to be the sole recipient of these overflight fees until the end of 2013.

Nevertheless, the imminent loss of this windfall is a huge blow to Aeroflot. The royalties are hidden within Aeroflot’s accounts, but analysts estimate that Aeroflot received around $400m in 2008 at a gross level, although one analyst calculates that a hefty proportion of this was passed on to state aviation bodies, leaving around 30% to go to the bottom line of Aeroflot. Even if this is accurate (and other analysts think that the percentage that remains with Aeroflot is much higher than 30%), that was still a hefty $120m boost in 2008, without which the airline would have recorded an $83m net loss.

Under an interim agreement signed between Aeroflot and the Russian air transport ministry earlier this year, the fees at a gross level will be reduced this year by as much as 50% (though the impact at a net level is as yet unclear), though they will remain substantial all the way to the end of 2013.

That presents a huge challenge for Aeroflot, and that may be why Valery Okulov, the long–serving CEO of the airline (and son–in–law of Russian ex–president Boris Yeltsin), was in effect fired after not being “nominated” to the company’s board earlier this year for the first time since 1997 (although he then became a Russian government deputy minister, in charge of civil aviation).

His replacement in April was Vitaly Savelyev, who was previously a vice president of AFK Sistema, a Moscow–based conglomerate, where he was in charge of a telecoms business unit. He was also a Russian deputy minister for economic development between 2004 and 2007 and has wide experience in banking and finance.

Freezing fleet renewal

He has been charged with preparing Aeroflot for the loss of these overflight fees, and unsurprisingly Savelyev’s first move in his five–year tenure was to signal that everything that Aeroflot did was up for review. A full strategic review of every part of the group will be completed before the end of 2009 (and will, for example, examine whether to outsource major parts of the group, such as ground handling and maintenance), but in June Savelyev announced a number of actions that are being implemented immediately — a halt to fleet renewal, plus cuts in staff. The group has a fleet of 155 aircraft, of which 102 are at the mainline (see table, left). However, the Aeroflot mainline has 107 aircraft on order, which Savelyev says is “more than enough”. Through the summer Aeroflot re–examined its capacity requirements, and this led to the postponement of deliveries for five A320 family aircraft, including two A320s from the first quarter of 2010 to early 2011 and early 2012, and three A321s from the third quarter of 2010 to 2012. However, all the deliveries planned for this year (18 A320s and six A330s) will be delivered as scheduled, since Aeroflot is committed to disposing of all its Tupolev aircraft by the end of 2009 as part of a drive to attract more business passengers and to become more fuel–efficient.

Once the Tu–134s and Tu–154s go, the average age of the fleet will come down from 10 to five years, although six IL–96s will stay until 2016, when they (and Aeroflot’s A330s and 767s) will be replaced by the first deliveries of 22 A350s and 22 787s on order. Until then the IL–96s will be used domestically and on a handful of international routes (such as to Havana and Hanoi), and some of these aircraft may be transferred to a new charter subsidiary, as the charter market is still an important part of the Russian aviation sector.

From 2016 Aeroflot will have just four models — 787/A350s for long–haul, A320 family aircraft for medium–haul and Sukhoi Superjet 100s for short–haul. Aeroflot has orders for 30 Superjets (plus 15 options), although the first of these regional aircraft will now not be delivered to Aeroflot until 2010; the first aircraft was previously due this year, and Aeroflot is already selling tickets for the first routes that will use the Superjet (from Moscow Sheremetyevo to Chelyabinsk and Astrakhan).

Despite the delay a cancellation of this order is unthinkable politically, as the 75- 90 seat aircraft is seen as being crucial to the future of aircraft manufacturing in Russia. The first 10 aircraft will be leased to Aeroflot from VEB Leasing and financed by a $250m credit line provided by the Vnesheconombank (known as VEB), the Russian state–controlled development bank, on 12–year contracts. This same bank is also financing the Superjet manufacturing programme after Vladimir Putin, the controversial Russian prime minister, promised $200m in further state funding earlier this year, without which Sukhoi said it would not be able to complete the programme given the current economic environment. However, whether the Superjet will receive significant (or indeed any) orders against its Embraer and Bombardier rivals outside of the former Soviet Union countries remains to be seen.

Staff reduction

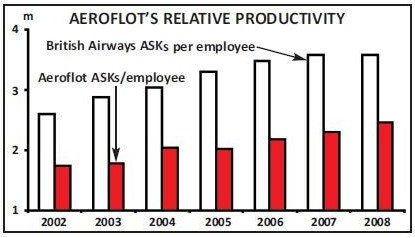

In terms of finance, capex for the new aircraft appears affordable, thanks to the final few years of the Siberian fees, more than generous financing from state–owned Russian banks and reasonably good cash flow at the airline. But Savelyev is now making an important statement that all further fleet development is now frozen, at least for the foreseeable future. Aeroflot is to reduce its workforce from 15,000 to 9,000 (a cut of 40%) within the next two or three years, in order to bring its productivity more into line with European competitors. As a productivity measure Savelyev uses the informal 1,000 employees per 1m passengers per year aimed for by European airlines, and under this measure Aeroflot is substantially overmanned. Under a more conventional productivity measure, ASKs per employee, the airline has a long way to catch up with British Airways, for example (see chart, below).

This process has already started, with 2,000 positions due to go by early 2010. In the summer Aeroflot also reduced its senior management by cutting deputy CEO positions from 13 to nine, and in addition introduced a pay freeze for all staff.

Altogether Aeroflot expects to cut its costs by a massive 25% in 2009, ahead of an anticipated fall in revenue this year of around 20% thanks to falling passenger traffic to/from and within Russia.

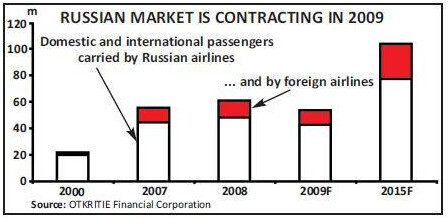

That drop in demand is the second major challenge that Aeroflot faces (on top of the loss of overflight fees). A long period of passenger growth through the 2000s in the Russian domestic and international markets (Russian airlines were barely affected by September 11) peaked in 2008, when Russian airlines carried 49.8m passengers, but that has come crashing to a halt this year thanks to the global economic crisis. RPKs at Russia’s airlines are expected to fall by between 10- 15% this year, and according to Russia’s Federal Air Transport Agency (FATA), domestic and international passenger traffic fell 17.5% in the first–half of 2009, although the fall at Aeroflot was less than this. In the January–June period mainline Aeroflot carried 3.9m passengers, 12.1% down on the first–half of 2008, at a load factor of 63.5%, with the total group carrying 4.8m passengers, an 11.5% fall year–on- year.

However this passenger downturn is expected to be a temporary blip, as Russia is still one of the least developed aviation markets in continental Europe. The fall in traffic is expected to stop in the third quarter of this year, with analysts predicting growth again in the fourth quarter. That is the best possible scenario for Aeroflot as the fall in traffic through the first–half of 2009 gave the newly–appointed Savelyev the ammunition to radically cut back costs at an airline that has never really had to tighten its belt before.

But the underlying long–term passenger trends for Russia look positive. According to the latest Airbus Global Market Forecast, the annual average growth rate for passenger traffic over 2009–2028 is forecast at 4.9% in the Russian domestic market, the same rate as in the Russia–Western Europe sector. And there are much higher rates for Russia–Asia (6.2%) and Russia–US (7.3%).

Aeroflot currently has a 39% share of traffic to/from the country and 11% of domestic Russian traffic, but a worrying statistic for Savelyev is that Aeroflot makes losses on approximately 40% of the routes it currently operates.

That percentage will fall once the staff cuts and fleet renewal kick in, but another key factor in bringing this percentage down is outside of Aeroflot’s control – the number of competitors that Aeroflot has to face within Russia. There are at least 250 commercial airlines operating in the ex–USSR, of which 170 are in Russia, although a large proportion of these carriers are small and/or in dire financial straits.

Indeed Gazprombank says that Aeroflot will be the “the key beneficiary of the ongoing consolidation” in Russian airlines, and that “small regional airlines overburdened with debt and limited access to financing won’t survive in the current market environment, with substantial decreases in passenger and cargo volumes”.

That will be a welcome development for Aeroflot, but probably will not diminish the need for it to severely restructure its route network at some time in the not too- distant future.

Sheremetyevo boost

Of course Aeroflot will hold on to as many of its profitable internal routes as possible, although here it is coming under pressure from the Russian competition regulator, which ruled recently that Aeroflot abused its dominant position on a domestic route between Krasnoyarsk and Norilsk by charging fares of $1,100 (when the maximum authorised fare was $250). The regulator fined Aeroflot the amount of all the excess revenue over $250 per flight on this route, although it’s unclear just what the total amount comes to. A priority for Aeroflot is to ensure better feed into its long–haul flights at its main base, Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, which has been a continuing problem for Aeroflot.

The situation should be improved greatly when the new terminal 3 (S3) at Sheremetyevo opens in the fourth quarter of this year. This will double capacity at the airport, with the new terminal initially adding capacity of 8m passengers a year, extendable to 12m. All Aeroflot’s and SkyTeam’s international flights (other than to the US and a handful of Asia/Pacific destinations) will move to S3, and the airport (and Aeroflot) hopes that these new links will help Sheremetyevo regain leadership of the domestic market, which it lost to Domodedovo in 2005.

Aeroflot owns 53% of S3, although this is costing the group many hundreds of millions of dollars in capex. Indeed Aeroflot’s long term–debt rose by 5.3% in 2008, to $1.3bn, with more than a third of that debt being finance lease obligations and $575m being long–term loans for the construction of S3. However, the airline says the development of S3 will generate $200m of additional revenue in 2010, rising to $300m a year afterwards.

Expanding flights at Sheremetyevo also gives the airline another benefit — reduced fuel costs. Aeroflot has not carried out fuel hedging in recent years, and although it buys 25% of its fuel abroad (at prices that are cheaper than available in Russia), within Russia it purchases as much fuel as possible at Sheremetyevo. Bulk agreements with Russian fuel companies at the airport mean that, on average, fuel purchased there is 16% cheaper than the cost of fuel bought anywhere else in Russia, according to statistics provided by FATA.

But while S3 will be a major boost to Aeroflot, there are many other problems that have to be tackled. Among the priorities is sorting out the mess at the group’s subsidiaries. Both Aeroflot Aeroflot–Don (set up in 2000) and Aeroflot–Nord (launched in 2004) racked up large losses in 2008, and to make matters worse the Russian authorities imposed operating restrictions on Aeroflot–Nord this summer following an investigation into the crash of a 737–500 last year, which a report said had partly been caused by inadequate training and a series of maintenance problems at the airline. Both airlines have an eclectic mix of models, and like the mainline these subsidiaries will reduce this variety over the next few years.

Short-term pain, long-term gain?

While Aeroflot is hopeful that both Aeroflot–Don and Aeroflot–Nord can return to profit in 2009 another subsidiary – Aeroflot–Cargo – has even greater problems. Aeroflot spun off its cargo operation as an independent subsidiary in 2006, and it now specialises in routes between Europe and the Asia/Pacific region using MD–11Fs and 737s. But its performance has been dire, and it has come close to being declared bankrupt. Aeroflot now wants to reabsorb Aeroflot–Cargo back into its mainline operation, where it’s hoped that direct control will help turn around the freight operation. In August Aeroflot released figures for the first–half of 2009, saying that operating profit rose 28.2% to $74.3m and net profit rose 48.1% to $103.5m, even though revenue fell 5% to $1.3bn. However, these are prepared under Russian accounting standards and so must be treated with caution until IAS results are released in September. Aeroflot still expects to post a profit for 2009 (helped by the depreciation of the rouble, since most costs are rouble based while revenues are largely received as Euros), although analysts are predicting that it may be very close to reporting a net loss (see chart, page 9).

Regardless of the 2009 result, it’s clear that Savelyev‘s focus is on sorting out Aeroflot’s immediate problems, given the drop in traffic this year and the imminent loss of the Siberian overflight fees. The new CEO is also looking to make significant service changes — as well as new in–flight catering, in July the airline announced a major re–branding effort, which includes retraining of its flight attendants (some of which have been sent to Singapore to receive training from SIA) and a new colour scheme to replace the current blue and orange, which Savelyev says (perhaps a bit too honestly) “evokes revulsion in passengers”.

This is not the first rebranding that Aeroflot has gone through in recent times, but this time around Savelyev appears determined to change the airline’s image for good.

European failure

More importantly perhaps, Aeroflot’s dabbling in western Europe has come to an end for the moment, with Savelyev saying that he “didn’t see prospects in Europe” for mergers and acquisitions, given that it faces substantial problems in being a non- EU airline (which restricts it to a 49% stake in any EU airline). And while Aeroflot has other priorities closer to home, it just cannot afford to invest in a European airline (from both a financial and managerial resource point of view) anyway, even at the bottom of the aviation cycle. Aeroflot has had an abysmal track record in Europe. After a failed bid for Alitalia in 2007, Aeroflot was part of the Darofan consortium that bid unsuccessfully to buy CSA Czech Airlines earlier this year (after the Czech government put its 91% stake up for privatisation) – Aeroflot then stated that “following a thorough examination of CSA’s financial and operational situation, Aeroflot detected considerable risks in the bid, which would have entailed serious financial obligations at a time of a global financial crisis”.

Although the right decision, that was a complete about turn from what Okulov, the previous CEO, said only a few months previously (when he stated that extending the long–term co–operation between the two airlines into a merger would enable both airlines to become more profitable).

Another near miss was with Malev, which Aeroflot came close to managing on a contract basis at the start of 2009 under a restructuring plan put together by its new owner, AirBridge, following the Hungarian carrier’s privatisation. In April, Aeroflot was also put forward to buy part of Blue Wings, after the Dusseldorf–based airline (which operated primarily to Turkey) was grounded temporarily by the German authorities due to concerns about its finances. But this deal was largely political, due to 48% of the airline being owned by Russia’s National Reserve Corporation, which also holds 30% of Aeroflot (the Russian government owns another 51.2%). Aeroflot’s management apparently objected to the acquisition, saying it would give little benefit to the Russian airline, and the deal eventually came to nothing.

While in the longer run a merger or acquisition of a major European airline might make strategic sense for Aeroflot, the short- and medium–term imperative is to sort out Aeroflot’s cost base. The only justifiable merger or acquisition might be within Russia, as part of an attempt to strengthen Aeroflot’s position domestically as smaller players go under or consolidate.

Last December Aeroflot said it would bid for the 25.5% stake in S7 that the Russian government was selling, although this led to anti–competitive concerns by the state anti–monopoly regulator, and appears even more of a non–starter now that S7 is joining the oneworld alliance (incidentally Star does not yet have a member in Russia).

There are plenty of other potential targets in Russia, although Savelyev will need to pick his acquisitions carefully, because as one analyst puts it, there will be “a second wave of bankruptcies among local air carriers on the back of their limited access to cheap fuel and a substantial decrease in passenger and cargo turnover”.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | ||||||

| Aeroflot Russian Airlines | 1 | |||||||

| A319 | 14 | |||||||

| A320 | 31 | 9 | ||||||

| A321 | 10 | 16 | ||||||

| A330 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| A350 | 1 | 22 | ||||||

| 737-300 | ||||||||

| 767-300ER | 11 | 22 | ||||||

| 787-8 | 3 | |||||||

| MD-11F | ||||||||

| IL-96-300 | 6 | |||||||

| Tu-154M | 23 | 30 | 15 | |||||

| Superjet 100-95 | 102 | |||||||

| Total | 107 | 15 | ||||||

| Aeroflot-Nord | 1 | |||||||

| 737-300 | ||||||||

| 737-500 | 16 | |||||||

| An-24/26 | 7 | |||||||

| Tu-134 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 34 | |||||||

| Aeroflot-Don | 3 | |||||||

| 737-400 | ||||||||

| 737-500 | 7 | |||||||

| IL-86 | 4 | |||||||

| Tu-134 | 1 | |||||||

| Tu-154 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 19 | |||||||

| Group total | 155 | 113 | 15 | |||||