Japan Airlines: At last, a radical restructuring

October 2009

Acombination of political change, recalcitrant banks and a steep recession is giving Japan Airlines (JAL), Asia’s largest carrier, a unique opportunity to get its house in order. Plans currently being drafted with the help of a government–appointed expert panel suggest a drastic restructuring in the coming months that will also fix balance sheet issues. But will the creditor banks co–operate, or will JAL have to restructure in bankruptcy?

In mid–October the Tokyo banking scene was in a flux as analysts and bankers were trying to figure out the implications of a massive Y600bn ($6.6bn) financial aid package that JAL was planning to seek from its creditor banks. According to the leaked reports, JAL is looking for Y300bn in debt–for–equity swaps and loan waivers, plus Y300bn in new loans from the banks. In addition, the airline reportedly wants a capital boost of Y150bn from private investors and the government.

A rescue package of that size would be costly for the banks, which will be deciding in the coming weeks whether or not to cooperate. If discussions with the banks fail, reorganisation under bankruptcy is a possible scenario for JAL.

A time for hope

This is clearly a very low point for the airline, which has seen its share price collapse in recent weeks, giving it a market value of just Y276bn. In mid–October both Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s lowered JAL’s credit ratings, amid growing alarm about the scale of the rescue effort needed and doubts about the airline’s ability to recover. However, the situation also offers new hope for the established carrier, which was fully privatised in 1987 but never really shook off the flag carrier mentality and other ills associated with government ownership. One way or another, JAL is now going to get an opportunity to restructure thoroughly.

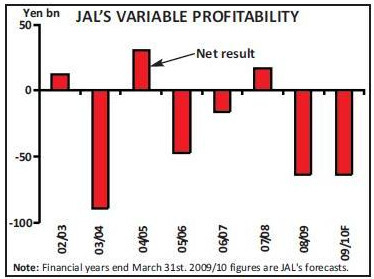

Before the recession, JAL had a decade of persistently weak annual results – either small losses or modest profits. A series of restructuring efforts failed to solve the basic problems: high labour costs, a less efficient fleet than its rivals, uncompetitive route structure, a bureaucratic corporate structure, militant unions and poor morale. In 2007/08 JAL staged a promising recovery, but that was short–lived because of the fuel price hike and subsequent economic downturn.

JAL has been devastated by the global recession because of its heavy exposure to international routes and business traffic. In the June quarter, its international passenger revenues plummeted by 46% and total revenues by 32%. It had a negative 26% operating margin and posted its largest–ever quarterly net loss, Y99bn ($1.1bn). JAL is now headed for its second consecutive annual net loss – currently forecast to be $63bn in fiscal 2009/10, following last year’s Y63.2bn loss.

In June JAL received a Y100bn ($1.1bn) “emergency” loan through the state–owned Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) – the third time it had sought government assistance since 2001. But it was clear all along that JAL would need significant further liquidity this year.

The key problem has been that the banks have balked at providing JAL with more funds unless the carrier comes up with a solid and achievable turnaround plan and the government makes a firm commitment to support JAL.

Conflicting signals

August saw a new development that fundamentally changed the funding climate for JAL and gave the banks new worries: the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) swept to power in a landslide election victory, ending five decades of nearly unbroken rule by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Somewhat confusingly, the more left–wing DPJ vowed to place greater scrutiny on the use of state funds, which the LDP had distributed quite freely to companies like JAL. The new administration has stressed that it will not allow JAL to fail and that Japan needs to maintain its two major airlines. However, the financial community has been a little spooked by the conflicting signals sent by the DPJ. The party wants to support ailing firms, while also reigning in wasteful government spending. Its policy stance is to provide for local needs and preserve jobs; yet it is now pushing for a restructuring at JAL that requires cutting unprofitable domestic service and drastically reducing staff numbers. In late September S&P noted the “need to closely monitor the future framework and direction of government support under the new Democratic Party of Japan administration”.

In late September, as part of its state aid application, JAL submitted a new turnaround plan that proposed cutting costs by 30% over three years, reducing the workforce by 14% (6,800 jobs) and eliminating 50 unprofitable routes.

But the lenders and the government dismissed JAL’s proposals as inadequate. Transport minister Seiji Maehara then appointed a new five–member “task force” to draw up a more radical restructuring plan. The draft of the plan is due by the end of October.

At that point a decision was also taken to shelve the alliance talks that JAL had hoped to conclude with either American or Delta by mid–October. JAL needed to focus all its attention on restructuring, and the possible Y30–50bn ($330–550m) investment by the winning bidder would not have made much difference. (The main immediate benefit would have been to improve the fund–raising climate for JAL.)

The task force is mostly made up of restructuring experts from the former Industrial Revitalisation Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a government agency that assisted banks and struggling companies in 2003–2007. The team sent experts to JAL to study its accounts and internal situation.

There have been reports of some truly outlandish options being considered, such as breaking JAL into “good” and “bad” parts for a General Motors–type restructuring, or merging its international operations with ANA’s and dedicating it to domestic/short haul operations.

But as details of the draft turnaround plan began to trickle out in mid–October, it was evident that the task force is just going for deeper restructuring measures to try to get the banks to co–operate. The job cuts have been increased to more than 9,000, or nearly 20% of the workforce, and JAL’s president Haruka Nishimatsu is to step down and be replaced by someone from outside the company.

But the reports indicate that the route cuts may not be as sharp as what JAL proposed in September. The airline apparently wants to keep five of the 21 international routes it proposed cutting because it now believes that they could be made profitable. (Could this be a sign of tentative demand recovery? IATA reported in mid–October that Asian airlines are starting to sell more premium seats.)

Balance sheet restructuring

It is also believed that the draft plan proposes reducing JAL’s pension obligations from the current Y330bn ($3.6bn) to Y100bn ($1.1bn) by substantially slashing pension benefits – something that JAL has already been working on since earlier this year. It will not be easy because the plan will be fiercely opposed by JAL’s retirees.But the most promising aspect of the plan is the likely balance sheet restructuring. JAL is nowhere near insolvent, but it has a weak balance sheet, extremely weak cash reserves and heavy upcoming debt maturities. At the end of June, JAL had total assets of Y1,696.7bn, total liabilities of Y1,517.9bn, long–term debt of Y881m and stockholders’ equity of Y279m. Its lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio is in the low–90s – higher than the leverage ratios of other major Asian and European carriers but lower than the US legacy carriers’. Its June cash position was a pitiful Y109.8bn, or around 6% of annual revenues – the norm for global airlines these days is 15–20%, and in the US less than 10% is considered bankruptcy–level.

JAL’s cash reserves have historically been poor, which has meant that the airline has repeatedly had to go begging for funds. The only exception was in March 2008 when, following a strong year, the cash position temporarily improved to 15.9% of annual revenues.

A substantial balance sheet restructuring now will hopefully improve JAL’s financial flexibility significantly. The airline should have the reserves to ride out tough periods that inevitably occur in the aviation business, be able to borrow through normal commercial channels and be able to tap the capital markets for funds.

It is possible that the impact of the restructuring on the banks could be softened, for example, by raising funds through asset sales. Even after a significant shedding of assets in recent years, JAL still has numerous wholly or partly owned subsidiaries that could be monetised.

But the government has also acknowledged that public funds may be necessary to accomplish the restructuring. One possibility would be to inject funds through the DBJ under an emergency aid programme set by the LDP administration for non–financial companies hit by the global recession.

Another possibility would be to apply for assistance by the Enterprise Turnaround Initiative Corporation of Japan (ETIC), a new government–backed institution that opened for business on October 16th with the ability to procure up to Y1,600bn ($18bn) in funding in the current fiscal year. The ETIC is similar to the former IRCJ (where the JAL task force members came from). It will operate like an investment fund, investing in and buying debt of companies with weak balance sheets and assisting them in restructuring. ETIC could also help companies that have filed for court protection from creditors.

As a last resort, JAL could file for bankruptcy. Japanese bankruptcy law is similar to US laws and has a fast–track process called “civil rehabilitation”. The government would be loathe to see that happen, but many argue that is not necessarily a bad option for an airline in JAL’s complicated situation, with legacy costs, labour and pension cost problems and eight militant in–house unions.