United: responding well to tough times - or cutting too deep?

October 2008

United’s parent UAL Corporation has in recent months been at the forefront of industry efforts to adjust to the tough fuel environment. The Chicago–based airline is contracting dramatically this autumn, as indicated by a 100–aircraft, 22% reduction in its mainline fleet and a 16% cut in domestic mainline ASMs in the fourth quarter. UAL is trimming non–fuel costs by $500m this year, is targeting $700m of incremental ancillary revenues in 2009, has raised $1.7bn of liquidity this year and recently forged a promising marketing alliance with Continental. Is all of this enough to weather the current storm and ensure longer–term survival? Or could UAL even be cutting too deep and risking its market position?

UAL emerged from a three–year Chapter 11 reorganisation in February 2006 with an improved cost structure and balance sheet but still much work left to be done on both fronts. Unlike Delta and Northwest in their respective Chapter 11 visits, United did not get its unit costs below the typical legacy carrier range. Also, despite the extensive Chapter 11–facilitated debt and lease restructuring and the shedding of pension obligations, UAL remained heavily leveraged, with an adjusted debt–to–capitalisation ratio in the high–80s and similar to AMR’s.

UAL’s post–Chapter 11 financial performance has been somewhat inconsistent (as one Wall Street analyst described it). In 2006 and early 2007 the company’s profit margins lagged behind those of its peers. Then UAL succeeded in closing the gap, reporting operating and pre–tax profits of $1bn and $600m–plus for 2007, thanks to a solid cost performance and one of the best RASM improvements in the industry. But this year UAL has again been trailing its peers; its negative 7% pre–tax margin in the second quarter was the worst among the seven large network carriers.

Some of the inconsistency is due to fresh–start accounting associated with emergence from Chapter 11. Also, in recent quarters UAL’s margins have been negatively affected by weak fuel hedging positions and the relatively large number of older, less fuel–efficient aircraft in the fleet. UAL claims that it continues to lead its peers in free cash flow (defined as cash flows from operations less capital expenditure, fuel hedge collateral received and purchase deposits paid). In the 12 months ended June 30, UAL was the only one of the top six network carriers to achieve positive free cash flow (some 0.5% of total revenue).

Labour strain

United’s greatest strengths are its unrivalled global route network and being one of the world’s best known brands. Because of those attributes, there has never really been serious doubt about its survival prospects and UAL has enjoyed much support from the financial community. But United’s labour relations continue to be strained. The airline has a history of labour strife — something that has raised questions about its corporate culture, though much of the current anger stems from the Chapter 11 sacrifices and the deep cuts implemented this autumn. It has been painful to watch the management and pilots at total loggerheads, fighting one another in court, in the middle of an industry crisis. The pilots staged work slowdowns in July, in opposition to UAL’s downsizing plans and to pressure the management to reopen a contract that becomes amendable in early 2010, which must have contributed to UAL’s losses.

UAL’s financial prospects, like those of its peers, have improved materially in the past couple of months, in the first place because of the significant decline in fuel prices. After peaking at around $147 per barrel in early July, crude oil has returned to the $100-$110 level last seen in April, even briefly dipping to the low–90s in the wake of the Wall Street crisis in mid–September. Second, the profit out–look is better because US airlines are moving ahead with a massive 11%-plus aggregate domestic capacity reduction in the fourth quarter, which should give them pricing power. Third, demand has held up well so far.

Focus on liquidity

But many concerns remain. Oil prices continue to be high and extremely volatile. Demand is likely to weaken as the economic picture worsens and fares continue to rise. One of the biggest concerns is that business travel demand will weaken, both domestically and globally, as a result of the credit crisis and a potential full–blown recession. Therefore the significant capacity cuts, which began in earnest in September, and other survival measures will have to be maintained. What exactly has UAL done to ensure its survival? In recent months the main focus at UAL, as at other US carriers, been on maintaining and boosting liquidity. "With changing market conditions and volatile fuel prices, as we all know, cash is king", noted UAL’s CFOelect Kathryn Mikells at a late–September conference, adding that the Wall Street crisis has made an appropriate level of liquidity even more critical.

UAL is well positioned on this front. First, its current liquidity position is adequate. The company expected to end the September quarter with total cash of $3.5bn, about 17% of this year’s revenues.

Second, UAL enjoys positive free cash flow and has modest calls on its cash, including no plans for new aircraft, a modest $450m non–aircraft spending budget in 2008 (recently reduced from $650m) and limited debt maturities.

Third, even after significant capital–raising in recent months (some of which was used to reduce debt), UAL has better flexibility than many of its peers to further improve liquidity. While any plans to sell assets such as the FFP and the aircraft maintenance business have obviously been shelved, the airline has $3bn in high–quality unencumbered hard assets that can be sold or used as collateral in financing transactions. About $2bn of those assets are aircraft, with spare parts and engines accounting for another $840m.

The recent moves included raising $550m in cash through a combination of asset sales, secured aircraft financings and the release of restricted cash. Subsequently, UAL also renegotiated agreements with its affinity card provider and credit card processor that in aggregate will boost liquidity by $1.2bn. Those deals included a $600m forward- sale of frequent–flyer miles to Chase (which is expected to generate an additional $200m in cash over the next few of years) and a reduction in the credit card hold–back from $385m to $25m (the reduction was dramatic because the $385m hold–back dated from the Chapter 11 exit agreement). Significantly, these transactions enabled UAL to raise a lot of cash without touching its hard unencumbered assets.

The 116–strong, $2bn pool of unencumbered aircraft is diverse; it includes all of United’s mainline types. As of September 18, the company had already sold three of the 737s that are retired as part of the capacity reduction plan and felt good about the prospect of monetising the other unencumbered aircraft despite a tighter market.

Aggressive capacity cuts

A late–July JPMorgan report noted that UAL’s airport slots are also quite valuable and that Heathrow alone could be worth $500m. The MRO business has $280m in annual revenues, but divesting it could only take place with labour’s approval. UAL has been leading the US airline industry in necessary downsizing this autumn. The airline is slashing mainline domestic capacity by as much as 15.5–16.5% in the fourth quarter, while regional affiliate capacity will fall by 2.5–2.5%. Unlike its peers, United is also pulling back significantly in international markets, where ASMs are slated to decline by 7–8% in the current quarter.

Next year will see a further capacity reduction. The current plan envisages a two–year contraction rate (2009 over 2007) of 19.5–20.5% in mainline domestic ASMs, 6- 7% in international ASMs and 12–13% in consolidated system ASMs.

The cuts are being facilitated by the retirement of 100 mainline aircraft (22% of the total), including all of United’s 737s and six of its 30 747s. About three quarters of the 100 aircraft will be retired this year, with the remainder going in 2009. In conjunction, the airline is reducing its workforce by 7,000 by the end of 2009.

UAL is also eliminating Ted — the last remaining airline–within–an–airline in the US, though it was only created in February 2004 while UAL was in Chapter 11. The Denverbased unit was nothing more than a separate leisure–oriented brand; it never got its unit costs much below United’s. Its fleet of 56 A320s will be reconfigured to include United’s first class seats between next spring and year–end 2009.

The capacity cuts will be mainly through frequency reductions or aircraft down–gauging in under–performing markets, rather than eliminating service to many cities, so as not to degrade the overall ("world’s best") route system. While closing some seven stations this year, UAL retains a commitment to all five of its US hubs and feels that the planned cuts will not unduly damage any of them. Los Angeles is seeing a massive 20% capacity reduction in the fourth quarter, with Denver being cut by 16%, Chicago 12%, San Francisco 11% and Washington/Dulles 3%.

Like its peers, United is finding it easier to cut domestic capacity now that LCCs generally are in the same boat. The airline has only seen competitive inroads from Southwest (in Denver), with the other LCCs essentially being in a contraction mode.

Internationally, UAL is eliminating routes that are not performing well, including all service to Nagoya, Los Angeles–Hong Kong, Los Angeles–Frankfurt and Denver- Heathrow, and reducing service to Mexico City. The airline also postponed its planned San Francisco–Guangzhou service by a year to June 2009 and is delaying the launch of Dulles–Moscow by six months to March 2009. Those routes are either too expensive or risky to develop at present (China and Russia), their economics do not make sense at $100–plus oil prices, or their yields and profitability have suffered as a result of significant capacity addition. United’s management expects the capacity cuts to lead to significantly better revenue performance and reduced losses in international operations.

UAL first outlined its steeper capacity and fleet reductions on June 4, a week after terminating its merger talks with US Airways and a couple of weeks before announcing a marketing alliance with Continental, and has since then slightly added to the cuts. The overall aim is to "resize the business appropriately for the environment" in order to restore profitability. Specifically, the current cuts resize UAL to a fuel environment where oil averages $125 per barrel. This is probably still a reasonable assumption in light of all the uncertainty — or, if it turns out to be an overestimate, an earlier return to profitability would not be such a bad outcome.

As UAL downsizes, the management is determined to remove all the corresponding costs out of the system. One key component is the elimination of 1,500 or 20% of the total salaried and management positions this year. UAL is also reducing front–line positions by at least 5,500 or 12% by the end of 2009, hopefully mostly through voluntary programmes.

Otherwise, removing costs is made somewhat easier by the older fleet and the fact that variable costs (such as fuel) now form a larger proportion of total operating costs. The A320, which will be deployed in many markets previously covered by 737s, has a 16% lower fuel burn per seat than the 737–300/500s. The retirement of the 93 737s is expected to lead to a 2.5% improvement in the mainline fleet’s fuel efficiency. Including also the 747s, the 100 aircraft retirements will lower the average age of United’s fleet from 13 to 11.8 years.

United expects to sell the owned 737s (46 out of the 93 total) to operators outside the US, where demand apparently continues to be strong and where the returns are likely to be higher. Also, as UAL executives expressed it on September 18, "the capital markets will also logically support that the aircraft will be deployed outside the US". In other words, that capacity is likely to be permanently removed from the US market. United has retained AAR to help re–market the 737s, which, according to a September 16 press release, were available immediately. Many of the 47 leased 737s will come off lease this year or in 2009, so the retirement schedule looks feasible.

Despite the significant ASM reduction, United expects its mainline ex–fuel CASM to increase by only 1.5–2.5% in 2008, which is essentially the same as the guidance given in January when the airline expected its mainline capacity to be merely flat this year. This is a result of the expanded cost–reduction programme, which now anticipates $500m cost savings in 2008. Future targets will include maintenance costs, catering costs, salaries and wages (particularly in overhead functions), feeder service, efficiency improvements with partners and distribution and sales costs.

Reports from different US airlines indicate that product unbundling and ancillary activities are turning out to be a surprisingly lucrative revenue source. UAL has been at the forefront of pursuing the so–called "other" revenues. The management calls such activities a "very large opportunity", capable of producing over $1bn in annual revenue.

United’s efforts have focused on three areas. First, like its peers, it has been increasing existing ticketing, change and excess baggage fees. Second, United is creating new revenue streams by charging for a la carte service, such as checked bags, within North America. United led the industry with a $25 second–bag charge in the spring; all the legacy carriers followed. In June United followed American in adding a $15 charge for the first checked bag. In mid- September United doubled the second–bag fee to $50. The bag fees alone represent $300m of additional revenue in 2009.

Third, United has introduced what it calls "travel enhancement products". These include the "Economy Plus" and premium cabin up–sell programmes, which are expected to generate $275m of revenue in 2009, and new products like "Award Accelerator", which are expected to generate $100m of revenue next year. Award Accelerator, the most recent addition, enables customers to spend a little extra to double or triple their frequent–flyer miles; the first month brought in 20,000 sales or $1.5m of revenue.

Alliance plans

All in all, United is expecting more than $1bn in merchandising, up–sell and fee revenue in 2009, which would represent a $700m increase over the 2007 total. UAL’s post–Chapter 11 strategy has focused on finding a merger partner. But all of those efforts have failed, most recently the promising–sounding talks with US Airways that UAL abruptly terminated at the end of May. Instead, in late June UAL settled on a close marketing alliance with Continental, with whom it had explored a merger in April before Continental opted not to merge with anyone.

But UAL may yet have the last laugh, particularly if it manages to take the UA/CO alliance beyond a traditional partnership or, of course, if Delta and Northwest run into serious integration problems. Mergers are full of potential pitfalls and the bulk of the benefits can probably be achieved through an alliance.

The UA/CO alliance will include broad domestic and international bilateral code–sharing, linkage of FFPs, Continental joining the Star alliance, establishing a four–carrier immunised transatlantic joint venture that would also include Lufthansa and Air Canada (along the lines of the SkyTeam JV) and "developing plans for cost and other synergies that are not dependent on antitrust immunity".

On the negative side, this alliance will be a long time coming. It will not kick in until late 2009, at the earliest, because of complex contractual issues. First the Delta/Northwest merger has to close, so that Northwest loses its veto powers over transactions involving Continental. Continental then has to extract itself from its current alliance contracts with Delta, Northwest and SkyTeam — the principal contractual restriction will apparently not terminate until nine months after the closure of DL/NW. UAL and Continental will need to get antitrust immunity and government approvals for their alliance. And Continental has (wisely) indicated that it intends to transition out of SkyTeam and into Star "in a customer friendly manner".

On the positive side, the prospects for DL/NW closing and UA/CO gaining antitrust immunity and regulatory approvals appear good, given recent precedents. Continental’s and United’s networks are highly complementary, with little overlap, so they add value to each other and to customers. And the potential is there to create an absolutely powerful global alliance. Continental’s inclusion will make Star bigger than SkyTeam on transatlantic, accounting for almost one third of the US–EU market.

Prospects

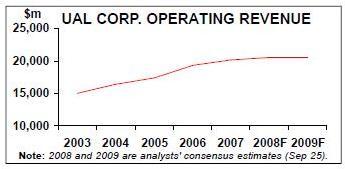

The airlines have said that their earlier merger discussions enabled them to identify efficiency opportunities that go well beyond those typical in a traditional alliance. In particular, there is enthusiasm about potential opportunities in IT, procurement, airport facilities and joint purchasing. Also, JVs similar to the one outlined for the transatlantic are planned for the Latin America and Asia/Pacific regions. Like the other US legacies, UAL is headed for a significant financial loss in 2008. The current consensus estimate (September 25) is a net loss before special items of $10.92 per share or around $1.37bn. However, a substantial improvement is anticipated next year, thanks to lower fuel prices and the impact of the capacity cuts and other measures implemented this autumn. The current consensus estimate for 2009 is a loss of $2.06 per share or $260m, though the range of individual analysts' forecasts is rather wide: from a profit of $4.48 per share to a loss of $9.58 per share. It all depends on fuel and economic trends, both of which are shrouded in uncertainty.

In addition to restoring profitability, United has another near–term imperative: turning around its operational performance, which has lagged seriously and is critical for retaining business passengers. In the 12 months to May 31 United ranked fifth among the six major network carriers in the DOT’s on–time rankings. The airline is now tackling the problem through measures such as adding ground and gate rest time at hubs and increasing spare aircraft from 2.5% to 5% of the scheduled fleet.

UAL’s current strategy is to target capital investments and resources on "projects that drive margins and improve customer experience". This means spending on the product rather than ordering aircraft. Much of the focus is on the new premium product being introduced on the 777s and 747s over the next two years; so far, 11 aircraft have been reconfigured to include the new "United First Suite" and full lie–flat seats in business class, and the product was brought to the Pacific market in August.

Orders for new long–range aircraft such as the 787 or the A350 are obviously long overdue, but UAL will not place them until it is making money — remarkable discipline that it shares with AMR and some other US carriers. But nor has UAL taken up its right (under a deal dating back from Chapter 11) to cancel any of its $2.2bn of A319 and A320 orders, despite stating in a July SEC filing that it was "highly unlikely" to take future delivery of those aircraft. Perhaps those orders could be converted for the A350?

Longer–term challenges include potential for labour disputes. Labour–management relations at UAL appear acrimonious enough to potentially inflict serious financial damage and, among other things, reduce flexibility to seek mergers in the future.

| Fleet | Average | |

| age (years) | ||

| A319-100 | 55 | 8 |

| A320-200 | 97 | 10 |

| 737-300 | 64 | 19 |

| 737-500 | 27 | 16 |

| 757-200 | 97 | 16 |

| 747-400 | 30 | 12 |

| 767-300 | 35 | 13 |

| 777-200 | 52 | 9 |

| Total | 457 | 13 |