Air Canada IPO: Unlocking the value in ACE Holdings

October 2006

In the coming weeks, if market conditions remain favourable, investors will get a rare opportunity to participate in the IPO of a major global airline. ACE Aviation Holdings has initiated the process of spinning off a minority stake in its wholly–owned subsidiary Air Canada. While certainly a less risky proposition than the LCCs floated in Europe and Asia earlier this year, is Air Canada — just two years out of bankruptcy — a sound long term investment?

According to the preliminary prospectus filed with the Canadian regulatory authorities on October 16, Air Canada will sell C$200m of Class A and B voting shares in the IPO. This will be followed by a secondary offering of Air Canada shares by ACE, the size of which is yet to be determined.

The shares will be sold only in Canada — like ACE, Air Canada hopes to trade on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX). However, non–Canadians will be able to participate by acquiring the so–called "variable" voting shares (Class A), which carry the same voting rights as Class B shares until foreign ownership exceeds 25%.

Why the spin-off?

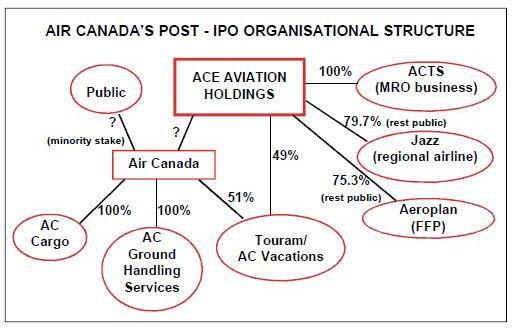

The spin–off comprises ACE’s "transportation services" business segment, which accounted for 76% of ACE’s revenues in the second quarter. In addition to Air Canada, the segment includes Air Canada Ground Handling Services, Air Canada Cargo and Air Canada Vacations. Under the post–IPO organisational structure, the ground handling, cargo and vacations businesses will report to Air Canada — the first two will be 100% owned by Air Canada, while Vacations will be a 51%/49% Air Canada/ACE joint venture. ACE will, of course, retain control of Air Canada through a majority interest. And Air Canada will continue to benefit from close business relationships — though there will be no ownership links — with the other three ACE business segments: Aeroplan (FFP), Jazz (regional carrier) and Air Canada Technical Services (ACTS, a full–service MRO organisation). Air Canada’s planned IPO is a key part of ACE’s strategy of maximising shareholder value by "unbundling" parts of its franchise to unlock the value of subsidiaries. The offering follows minority IPOs of Aeroplan (June 2005) and Jazz (February 2006), both of which were sold as income trusts and have delivered strong financial results. ACE currently holds 75.3% and 79.7% stakes in Aeroplan and Jazz, respectively.

The value–maximisation strategy was adopted following the reorganisation of Air Canada’s corporate structure immediately before the company emerged from an 18–month bankruptcy restructuring in October 2004. Air Canada and its business units became stand–alone entities or limited partnerships under a newly created holding company, ACE, which then set about to strengthen the units and further develop synergies between them. It is quite an innovative strategy — the Aeroplan IPO was the first–ever monetisation of an airline FFP.

The C$200m or so funds that Air Canada hopes to raise through the IPO will also come in handy, given the airline’s significant fleet renewal programme.

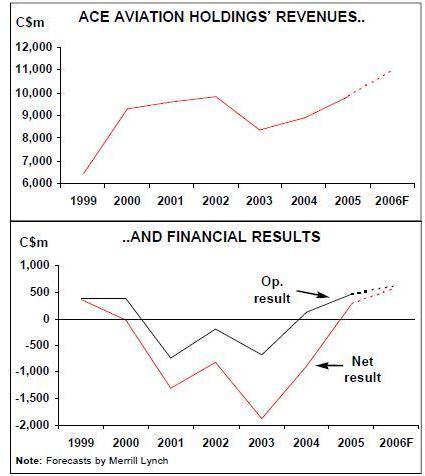

The IPO is possible because ACE has staged an impressive financial turnaround in the past two years. After three and a half years of operating losses totalling C$1.73bn, the company returned to profitability in the third quarter of 2004 and posted a modest C$117m operating profit for that year. This was followed by impressive C$452m and C$258m operating and net profits in 2005, achieved despite a C$592m higher fuel bill. In the current year ACE is heading for an operating profit approaching C$600m.

Air Canada returned to profitability earlier than the US network carriers, thanks to the steep cost cuts in bankruptcy, an improved domestic revenue environment after rival Jetsgo ceased operations in March 2005 and many innovative business strategies. That said, ACE’s profit margins now lag behind those being achieved south of the border — its 2Q06 operating margin was 6.7% and the full–year margin is likely to be lower.

Nevertheless, the IPO seems well timed. When it was announced, ACE’s share price had surged by 25% in the previous three months, from around C$29 to C$36, reflecting the recent decline in fuel prices and a further easing of competitive pressures when CanJet, a privately held Halifax–based airline, halted scheduled service in early September. Four days after the IPO filing, on October 20, the stock closed at C$38.24, nearing its 52–week high of C$40.

Air Canada's strengths

Many analysts who follow ACE have noted that the market is not giving full credit for Air Canada. Merrill Lynch’s Michael Linenberg said in an October 17 research note that his sum–of–the–parts analysis suggested that the market ascribes no equity value for the airline in ACE’s share price. Merrill Lynch "conservatively" arrived at a value for Air Canada of C$15 per ACE share by applying a 10% discount to US network carriers on a 2007 EV/EBITDAR basis. In the preliminary IPO prospectus, Air Canada lists as its strengths its position as the largest airline in various market areas, its innovative revenue model, strong RASM performance, strong financial position, premier FFP, strong brand recognition, and proven results oriented management team. The following are probably the most important factors:

- Dominant market position

Air Canada’s greatest strength is its dominant market position. It is not only the largest domestic operator, with a 60% ASM share (January–September 2006), but it also has 38% of the Canada–US transborder market and 45% of the long–haul international market. These figures represent more than twice the scheduled capacity of the second largest competitor in each segment.

Air Canada controls regional feed with its affiliate Jazz, which operates substantially all of its RJ and turboprop capacity on Air Canada’s behalf and is Canada’s second largest airline. In addition to serving thinner regional markets, Jazz also provides off–peak service in higher–density markets throughout Canada and to some US destinations.

Air Canada is the world’s 14th largest airline in terms of 2005 ASMs and has a strong global network. It has virtual monopoly of Canada’s international traffic rights and is likely to remain the country’s dominant long–haul international carrier for many years to come. In addition, Air Canada is a founding member of the Star Alliance, which extends its network coverage to over 840 destinations in 152 countries.

A balanced route structure also helps minimise risk. In the first half of 2006, Air Canada generated 41%, 20% and 39% of its revenue from domestic, transborder and long–haul international services, respectively.

- Innovative revenue model

One of the key earlier concerns was that Air Canada might not be able to retain a large enough unit revenue (RASM) premium over LCCs, given its higher cost levels. But so far at least revenue performance has exceeded expectations, which the company attributes to an innovative revenue model that enables it to compete effectively with LCCs (on pricing) and with leading international full service carriers (on products and services). The model "establishes a clear link between price and value" and enables Air Canada to provide for customers who value different aspects of its products and services.

The "branded fare strategy" was introduced domestically in May 2003 and expanded to certain US destinations in February 2004. In October 2005 Air Canada introduced a similar, simplified fare structure on some transatlantic routes, and the plan now is to take it to other international routes over the next two years.

The strategy offers five simple fare types (ranging from Tango, the lowest, to Executive Class, the highest), priced according to the built–in benefits in terms of flexibility, refundability, level of FFP mileage accumulation, lounge access, etc. But Air Canada goes a step further by also offering à la carte options to enhance each of the branded fares. Currently a Tango customer is able to buy seat assignment for a fee and obtain discounts by electing not to check luggage or waiving the right to make changes to the ticket. This autumn, Air Canada is adding à la carte options on all its branded fares, including the ability to pay for a meal and to access airport lounges.

It is the à $1 options that make Air Canada’s model substantially different from the approach pursued by other network carriers, which traditionally limit customer choice in an effort to optimise revenue. But the customisation concept has been very successful in other industries, such as cars and computers. It is evidently paying dividends at Air Canada, helping attract and retain customers and boosting revenues. For example, nearly 20% of Tango customers elect to purchase seat assignment, which has improved the base yield of the product.

Air Canada’s management believes that the new revenue model has contributed to higher load factors, yields, RASM and cost efficiency. The airline has achieved record or near–record monthly load factors for more than two years. The passenger load factor rose from 73.1% in 2003 to 79.5% in 2005. Quarterly domestic RASM has risen steadily, from about 15 cents in 1Q04 to over 18 cents in 2Q06.

- Premier FFP and strong brand

Because Air Canada does not have to share the domestic market with other large carriers, it has been able to build Aeroplan into a uniquely strong FFP. According to a recent business travel study, 91% of frequent Canadian business travellers (six or more trips per year) are Aeroplan members. The strategic relationship with Aeroplan provides a long–term stable revenue source for Air Canada.

Because of the breadth of the network, old–established and dominant market position, reputation for reliable operations and the creative new product strategies, Air Canada’s brand is one of the most recognised in Canada and widely recognised in North America and internationally. The brand will be further enhanced through fleet renewal and refurbishment of aircraft interiors.

- Strong financial position

The 2003–2004 bankruptcy restructuring process reduced Air Canada’s debt and capital lease obligations from C$12bn to C$5bn and gave the company a relatively healthy cash position of C$1.9bn. In April 2005 ACE raised over C$1bn in new liquidity through concurrent equity and convertible note offerings and by obtaining a new C$300m credit facility. This reduced the debt and lease obligations to C$4bn and improved cash reserves to C$2.1bn. Since then ACE has raised further funds from the partial sales of Aeroplan and Jazz, as well as from the sale of stock held in the merged US Airways–AWA — the latter raised more than US$200m, producing a nice profit on the original US$75m investment.

According to the preliminary prospectus, Air Canada expects to have more than C$2bn in cash after the IPO — an ample 22%-plus of last year’s revenues — plus access to a restated and expanded $400m senior secured revolving credit facility. Pro–forma accounts for the Air Canada Group (including Jazz, which will not be part of the post–IPO Air Canada), for June 30 and adjusted for the IPO, show cash of C$2.7bn and debt and capital lease obligations of C$3.9bn.

However, future funding needs are substantial, now that Air Canada is entering a period of accelerated fleet renewal, expansion and refurbishing. Projected capital expenditures over the next two years alone (through the end of 2008) amount to C$4.4bn, plus minimum lease payments in that period add up to C$1.1bn. Pension funding obligations are running at around C$470–500m annually in the next five years.

Cost and labour issues

Air Canada’s stated aim is to try to lower the cost of capital. It is not surprising that the underwriter line–up for the IPO includes at least ten financial institutions — five of them are being rewarded for providing credit facilities; the rest is pure relationship building as clearly they are not all needed to sell the offering. Air Canada evidently exceeded the targets of its 2003 cost–cutting programme, which aimed to reduce annual operating expenses by C$2bn or 20% between 2002 and the end of 2006. Labour cost savings have amounted to C$1bn (mainly through productivity improvements), aircraft rents were reduced by C$600m while in bankruptcy, and other sources have contributed at least C$500m in savings. Air Canada’s ex–fuel CASM declined from 14.5 cents in 2002 to 12.2 cents in 2005.

But that was not enough to take Air Canada anywhere near LCCs' cost levels; the CASM gap with WestJet, the main low cost competitor, is at least 3 US cents — more than the differential between most US legacy carriers and LCCs.

However, success on the revenue side has lessened the imperative to get costs closer to LCC levels. Air Canada now describes itself as simply "lower–cost" or "loyalty" carrier. Because of its dominant market position, strong FFP, virtual monopoly of Canada’s international traffic rights and innovative revenue model, Air Canada should — more than legacy carriers generally — be able to retain a large enough high–yield traffic component to justify a higher cost structure.

Like the US carriers, Air Canada now sees cost cutting as a continuous process to remain competitive. The fleet modernisation programme will help further reduce unit costs. In addition, Air Canada is trying to reduce internal costs by streamlining business processes. The airline also aims to lower distribution and processing costs through improved web–enabled technology — a new system for passenger reservation and airport customer service will be deployed from late 2007 or early 2008. Another goal is to reduce transaction and marketing costs with single–purchase and multiple–use products such as flight passes; recent weeks have seen two new offerings: "London Pass" (six prepaid one–way trips between anywhere in Canada and Heathrow) and "Unlimited Pass" (unlimited travel anywhere within North America, offered in several versions).

This year’s mid–term wage revisions, permitted by the concessionary collective bargaining agreements which were negotiated in 2003–2004 and which expire in 2009, have created new labour cost pressures. On the positive side, however, productivity is not a re–opener, and the parties originally agreed on two issues important at a unionised carrier: use of binding arbitration, if necessary, and no industrial action through 2009. Except in the case of pilots, who may also revisit certain pension issues, only wage revisions are permitted.

As of early October, Air Canada had settled the mid–term wage revisions with three of its five main unions (IAM, IBT and CAW) and several smaller groups. This year’s wage rates were raised by 1–1.6%, to be followed by typically 1.6–1.75% annual increases in 2007 and 2008. These are not insignificant increases, and the raises for the two most critical unions — pilots and flight attendants — are yet to be settled (the pilots are in arbitration and the flight attendants in mediation).

Separately, Air Canada expects to complete an earlier programme of reducing its non–unionised workforce by 20% by the end of this year. That programme was introduced in part to help offset the 2005/2006 hike in fuel prices.

Growth plans

In light of the history of labour problems, special efforts are being made to improve communication with employees. New initiatives include senior executive roadshows, an online dialogue with Air Canada president/CEO Montie Brewer, an employee suggestion programme, employee surveys, new knowledge sharing and team building opportunities and new grievance procedures. Air Canada’s post–bankruptcy North American strategy is to offer a high–frequency schedule on key routes, while maintaining competitive frequencies in other markets and adding new non–stop routes. Since October 2004 the airline has increased frequencies on 80 routes and added 17 new domestic and nine new transborder point–to–point routes.

The strategy has meant increased reliance on small aircraft. Two years ago ACE placed firm orders for 15 ERJ–175s and 45 ERJ–190s, plus 60 options for the ERJ- 190, all to be operated by Air Canada at pilot costs that are believed to be only slightly higher than JetBlue’s. The ERJ–175s were delivered by January 2006, and by the end of September Air Canada had also received 15 ERJ–190s, with the remaining 30 due to arrive by March 2008. The Embraer aircraft are both for growth and replacement of some older A319s and A320s. By the end of 2008, 70–90 seaters will account for 39% of Air Canada’s planned narrowbody fleet of 155 aircraft.

The new North America strategy has also meant a greater role for Jazz. The post–bankruptcy RJ orders also included 15 CRJ–705s and 15 CRJ–200s for the regional airline, all of which were delivered by the end of 2005. At the end of September Jazz operated 73 CRJs and 60 turboprop aircraft on behalf of Air Canada.

The new RJs have created many new transborder route opportunities, such as linking Toronto, Montreal, Halifax and Ottawa with new points in Florida and Texas, and East Canada hubs with points in California and Arizona. For its 2006–2007 winter schedule, Air Canada is significantly increasing its flights from Canada to leisure destinations in Florida, California and Las Vegas, meaning a 13% increase in seats.

But the main focus of Air Canada’s post post bankruptcy strategy has been on international markets outside North America. The past 2–3 years have seen significant Latin American and Caribbean expansion, partly because of the opportunity offered by the US "no transit without a visa" policy, which has made transiting via Canada an increasingly attractive option. Recent route additions have included Montreal–Havana, Toronto- Santo Domingo and Montreal–Mexico City. This winter Air Canada is planning to add 25 more weekly flights to Mexico and also additional service to the Caribbean.

The other post–bankruptcy strategy has been to look for niche markets not served by other international carriers. New route additions in that category included Toronto–Delhi (via Zurich) and Vancouver–Sydney last year.

Air Canada continues to strengthen its transatlantic network, often by introducing service to existing European destinations from new Canadian points. This autumn it is adding Edmonton–Heathrow flights with 767- 300ERs, and Montreal–Rome 767–200ER service will follow in June 2007.

Otherwise, the focus is on building nonstop service to Asia particularly from Toronto, even though Vancouver remains the main Asian gateway. In recent years Air Canada has added Toronto–Hong Kong, Toronto- Beijing and Toronto–Seoul services. The biggest near–term growth opportunity is China, following a more liberal new ASA signed last year.

Air Canada will begin renewing its widebody fleet in March 2007 when it starts receiving the 777s. This is not significantly behind the original schedule (first three aircraft in 2006) that the airline had before it temporarily cancelled the order in June 2005 after its pilots rejected a tentative agreement on costs and other issues (the order was reinstated in November 2005). The airline has 19 777s on firm order, plus 18 options. The firm orders include six 777–200LRs and 11 777–300ERs — all scheduled for delivery by the end of 2008 — and two 777–200 freighters due in 2009. The 14 787s on firm order are scheduled for delivery in 2010–2011, plus there are 46 options.

Those two types will eventually replace all of Air Canada’s 12 A340s, as well as most of its 12 767–200/200ERs. The overall size of the widebody fleet (65 at year–end) will remain largely unchanged until the 787s arrive, after which the plan is to increase the operating fleet to 74.

Further spin-offs?

In addition to acquiring new aircraft, Air Canada commenced a major refurbishment of its existing aircraft in April 2006, which is expected to be completed by mid–2008. All existing aircraft except the A340–300s will get new seats, personal in–flight entertainment systems and in–seat power outlets. International executive class cabins will also get flat–bed seats. In August, when disclosing its second quarter results and intention to spin off Air Canada, ACE also announced that it expected to commence the process of "monetising" ACTS in late 2006 and that it was pursuing opportunities that realise the value of its remaining investment in Aeroplan and Jazz.

After Air Canada’s IPO, ACTS would be ACE’s only remaining wholly owned business unit. It was originally expected to be the next in the IPO line after Aeroplan, but its spin–off was delayed as it struggled with some unprofitable contracts. But a new management team and restructuring have helped — ACTS reported a modest operating profit for the second quarter. In September it also amended a problematic US$300m maintenance contract with Delta, further enhancing its prospects. However, ACTS’s monetisation is currently expected to be an outright sale rather than an IPO. ACE CEO Robert Milton indicated in August that several private equity firms had expressed interest.

It was previously believed that ACE’s likely goal was to be an aviation holding company with majority stakes in a number of thriving businesses. But the August announcements raised the prospect that the holding company structure could eventually disappear. Milton said that the board had actually come to the conclusion that it does not need to own any of the component companies — which can have just as beneficial relationships with each other through operating contracts as through cross–ownership — though it was not at all certain that ACE would follow that strategy.