China: Big Three dominate, expand and ally

October 2004

After a tough 2003, dominated by the effects of the SARS epidemic, Chinese airlines are looking forward to a profitable 2004 as the Chinese government finally begins to liberalise the aviation regime.

Virtually all China’s airlines saw passenger traffic plunge after SARS, with April–July 2003 being the worst affected months, but traffic recovered quickly from August onwards — particularly domestically — and international traffic returned to pre–SARS levels by the beginning of 2004.

But at the same time as the industry was battling the effects of SARS, the Chinese government came round to the view that China’s economy would benefit greatly from a faster liberalisation of the aviation regime.

This change in policy was probably motivated by increasing pressure from the US in the light of China’s WTO entry, though the need to prepare an adequate infrastructure for the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai also played a part.

In April 2004 the government introduced pricing reforms to domestic fares, allowing airlines greater leeway to set their own fares.

And in the same month — in a surprise move — the government followed up the "open skies" policy on the island province of Hainan (though only for international airlines) by announcing that from 2005 it was opening up Shanghai’s two airports to all domestic airlines, without restriction.

This was followed in July by the signing of an amended bilateral between China and the US. This allows an extra 160 frequencies a week on routes between the two countries and an extra 10 designated airlines, though the increases will be introduced gradually over the next six years. Under the previous amendment (agreed in 1999) China and the US were each allowed up to four designated airlines operating between the countries (currently United, Northwest, UPS, FedEx, Air China, China Eastern, China Southern and China Cargo Airlines), with no more than 54 frequencies per week.

Although talks between the two sides had been long and tortuous, political pressure combined with commercial lobbying from airlines such as Shanghai Airlines and American — which were blocked from operating between China and the US by the limits of the previous deal — was enough to achieve the breakthrough.

The two sides also agreed to talk again in 2006, which could lead to a further speeding up of the liberalisation timetable agreed in the latest amendment.

A new bilateral was also signed with New Zealand in May 2004, allowing routes between all cities in China and New Zealand, as opposed to the four–city limit allowed under the previous air services agreement.

Though there are no currently direct routes between the two countries, the amended bilateral will encourage services via stopovers in Australia, for example. And in July 2003 an expanded bilateral between China and Japan allows three more Chinese airlines — Hainan Airlines, Xiamen Airlines and Shanghai Airlines — the right to operate to Osaka, which had previously only been served by the Big Three — Air China, China Eastern and China Southern. But it’s not all good news for China’s airlines.

With fuel accounting for 25–30% of Chinese airlines' total costs, the rise in fuel prices over the past year is one worry that all airlines share. The government has imposed two fuel price increases in 2004 — a 13% rise in March and a 12% rise in August — and as a result all the Big Three airlines introduced fuel surcharges during the year. However, in the long–term the Big Three will benefit from China’s WTO membership, a condition of which is that the Chinese government’s monopoly on aviation fuel end by 2006, by which time the state fuel price has to fall back to world market prices.

And some vestiges of state interference appear to be as strong as ever. In August 2004 the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) replaced all three general managers at the Big Three — Li Jianxiang took over at Air China, Liu Shaoyong at China Southern and Li Fenghua at China Eastern.

The official reason for the change was that the outgoing general managers were in their early 60s and that the government was following a rule that senior managers at state–owned companies have to retire when they reached 60 (the replacements are aged 55, 46 and 54 respectively).

One of the first strategic decisions the new general managers will have to make is which global aviation alliance to join.

It’s likely that Air China will join Star, China Eastern link with oneworld and China Southern enter SkyTeam, as all three airlines have close ties with the respective members of these groupings. It would also suit the CAAC to have each of its main airlines in the three alliances.

The global alliances will boost the Big Three’s refocus on international expansion, which is becoming more of a strategic priority now that they dominate the Chinese domestic market; all three are adding international routes and capacity as fast as their resources allow.

The Chinese fleet

As the Chinese government’s consolidation plan takes effect, the Big Three airlines are becoming ever more dominant, with half a dozen carriers disappearing into the Big Three over the last 12 months.

In 2002 the three airlines (excluding non–integrated partners) accounted for 36% of the total mainland Chinese commercial fleet, but this rose to 38% in 2003 and jumped to 52% in 2004.

The battle between Boeing and Airbus for orders from the Chinese government is continuing — Boeing’s latest forecast is that Chinese airlines will need 2,391 new aircraft over the next 20 year, worth an estimated $197bn, while Airbus forecasts 1,530 new aircraft over the same period, worth $176bn.

Today the order book stands at 156 aircraft — almost double the outstanding orders as of a year ago (79) — and the total is likely to rise further over the next 12 months. The China Aviation Supplies Import & Export Group is close to placing a $2bn+ order for more than 50 7E7s. An MoU was signed with Boeing earlier this year, and detailed negotiations are now taking place. It is believed that each of the Big Three, as well as Hainan Airlines, want at least 8–10 7E7s, and further aircraft may be ordered for smaller carriers such as Shanghai Airlines and Xiamen Airlines (which China Southern owns 60% of).

Many of the aircraft are likely to be the long range 7E7–8 version, which Boeing aims to deliver from 2008 onwards.

A 7E7 order will build on the major contract of November 2003, in which the Chinese government ordered 30 737s for delivery in 2005 and 2006 — five 737–700s for Air China, eight 737–800s for Hainan Airlines; three 737- 700s and four 737–800s for Shandong Airlines, five 737–900s for Shenzhen Airlines and five 737–700s for Xiamen Airlines.

This came just a couple of months after a Chinese government order for five 757–200s, for Shanghai Airlines.

Altogether, of the outstanding order book, Boeing accounts for 37% (58 aircraft) and Airbus 49% (76 aircraft), compared with 30% for Boeing and 62% for Airbus in 2003. Of the current Chinese fleet of 869 aircraft (785 in 2003), Boeing models account for 520, or 60%, and Airbus 243, or 28%. 737s continue to be the most popular model, accounting for 34% of the fleet, followed by A320 family aircraft, with 17%.

Boeing is determined to close the gap with Airbus, and may be starting to benefit from the greater political pressure that the US now appears to leverage compared with the EU.

The US administration has long been pressing China to reduce its $100bn a year trade deficit, and is urging the Chinese to revalue the Yuan, which it believes is artificially kept low in order to boost exports and restrict imports. But currency revaluation appears to be out of the question at the moment, and the Chinese government may prefer the less painful step of placing large manufacturing orders with US companies in order to relieve the political pressure from the Bush administration. Yet Airbus is confident it can keep its order book ticking over in China. It is in talks with the Big Three and Hainan Airlines over potential A380 orders, which should be placed before the end of the year — though speculation is mounting that an initial order for 10 aircraft, worth $2.5bn, will be announced during President Chirac’s visit to China on October 8. The A380s would be used for international routes, and domestic services between major cities.

Over the next 12 months there may also be an upsurge in regional jet orders.

The Chinese government is encouraging domestic airlines to buy locally–produced regional aircraft — ACAC’s 85–seat ARJ21 and the Embraer ERJ–145. The purchase of foreign regional aircraft has been blocked by the Chinese government since 2001, but with domestic routes expanding fast airlines face little choice but order the newly–available local aircraft. China Southern wanted to buy 20 Brazilian–built Emb–145s in 2001, but was not allowed to carry out the purchase, and instead ordered six locally produced ERJ- 145s. Just 8% of the Chinese fleet are regional aircraft, but Embraer forecasts demand for more than 200 30–50 seat aircraft over the next two decades, while Boeing forecasts deliveries of 260+ regional jets in the same time period.

Air China

Beijing–based Air China recovered well in the second–half of 2003 after responding to the SARS crisis by targeted cost–cutting.

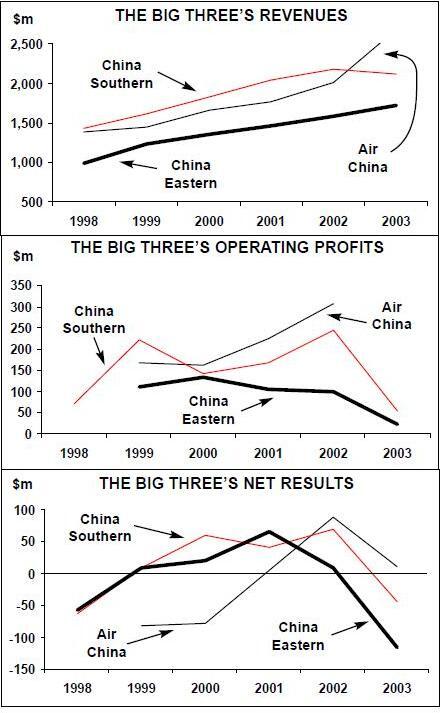

For 2003 the airline reported a 34% increase in revenue, to $2.7bn, but net profit fell to $11m, compared with a $89m net profit in 2002 (no operating figure was released). In 2003 Air China carried 18.05m passengers, down0.5% on 2002.

Half–year results are not available, but Air China is aiming for a net profit of Yuan 1bn in 2004 ($118m).

Air China has been busy strategically over the last 12 months. In February 2004 Air China agreed to pay a reported $60m for a 22.8% stake in Jinan–based Shandong Airlines (as well as 42% of Shandong’s parent company) with which Air China already code–shares.

Shandong is based in the north–east of China and operates 22 aircraft on domestic routes, so its acquisition will boost Air China’s national network, which is poor compared with China Southern and China Eastern.

Air China is also making disposals. In 2003 it separated out its cargo operations into Air China Cargo, selling 25% to Hong Kong conglomerate CITIC Pacific and 24% to Beijing Capital International Airport (which owns the cargo terminal at Beijing airport) for $423m earlier this year. Air China Cargo currently operates five 747s and in August ordered two 747–400 freighters for delivery in 2005 and 2006. Air China is also selling its majority stakes in two in–flight catering companies to CNAC for $44m.

Apart from the Shandong acquisition, Air China’s other major domestic move in the last 12 months is its plan to set up a hub at Guangzhou’s new Baiyun airport, which follows closely behind the launch of Air China operations in Shanghai. The Guangzhou hub will attract feed from southern China and is a direct challenge to Big Three rival China Southern.

More controversially, Air China will launch a subsidiary in Tibet by the end of 2004.

With five A319s and two 757s, the Lhasa–based airline will target business and tourist travellers to the country, though this will attract criticism as Tibet has been occupied by China since an invasion in 1950.

Internationally, in June 2003 Air China ended its code–share with Northwest, replacing it in October 2003 with a wide–ranging alliance with United, to include code–sharing on international and national flights, and an FFP link–up. Initially the airlines code–shared on a limited number of routes, but at the end of the year the US DoT later gave blanket approval for code–sharing to all beyond–gateway destinations in the US and China.

New international routes included Beijing- Milan, Beijing–Dubai, Beijing–Kuala Lumpur, Dalian–Beijing–Munich and Chengdu–Beijing- Paris (the latter is the first route between western China and Europe).

In February 2004 Air China started code–sharing with Dragonair on routes between Hong–Kong and four mainland destinations, while in May Air China signed a code–share deal with Air Macau. From March 2004 Air China began code–sharing on more than 105 flights a week with Star’s All Nippon Airways (ANA), to go alongside existing code–shares with Star members SAS and Asiana Airlines.

Air China is not a quoted company (unlike its Big Three rivals, which went public in 1997), but has plans for a long–delayed simultaneous IPO in Hong Kong and New York before the end of 2004 — though this is now likely to slip into 2005. China International Capital Corp and Merrill Lynch will underwrite the IPO, but are keeping quiet about details and timing. Up to 30% of the airline will be floated, raising between $500m-$800m (valuing the company at up to $2.7bn).

There is also a strong possibility that instead of a direct IPO, a holding company will be listed, which would contain equity in both Air China and Hong Kong–listed China National Aviation (CNAC).

CNAC owns 51% of Air Macau and 43% of Hong Kong’s Dragonair, and is owned by China National Aviation Holdings (CNAH), which is also the parent of Air China.

This structure would avoid fears that an Air China IPO on its own may not be particularly attractive. While Air China has the kudos of being China’s main international airline, many of the non–domestic routes are not profitable, and it brand lags far behind its international competitors in attracting lucrative business passengers. Prospective investors also know that China Southern’s shares have yet to recover to their IPO price, while China Eastern’s are only slightly higher than the IPO price.

Reports from China in September 2004 also suggested that code–share partner Lufthansa may buy 10% of Air China prior to the listing, though this was denied by the German airline. More likely is the sale of a strategic stake to Hong Kong–based investors with relationships to the Beijing government, such as CITIC Pacific, although an investment by a US or Asian airline can’t be ruled out — the most likely candidates being Cathay, Singapore, United and Northwest.

Part of the IPO proceeds will be used to pay for new aircraft. Air China operates a fleet of 132 aircraft and has 18 737NGs and A320 family aircraft on order, with the likelihood of A380 and 7E7 orders to come.

The latest order came in September 2004, for another seven 737–700s, with delivery by mid–2006.

Incidentally, as its fleet increases Air China is following the lead of Hainan Airlines and recruiting foreign pilots, initially A320 rated aircrew from New Zealand.

Air China remains the Chinese airline most likely to become a member of the Star global alliance. Air China code–shares with Star’s United and Lufthansa, and since 1989 Air China has also been a joint venture partner with Lufthansa in Aircraft Maintenance and Engineering (Air China owns 60% and Lufthansa 40%). The maintenance company is profitable, and in August the two airlines agreed to extend the joint venture until 2029 as well as injecting $100m in capex investment into the Beijing airport–based company.

China Southern

China Southern was particularly hard hit by SARS as it is based in Guangzhou in the south of China, the centre of the epidemic. In April, May and June 2003 RPKs fell by 40%, 84% and 62% respectively, but domestic traffic returned very quickly and by August RPKs had risen by 23% year–on–year.

Nevertheless, in 2003 revenue dropped 3% to $2.1bn and operating profit fell to $55m compared with a $245m operating profit in 2002, while at the net level China Southern racked up a loss of $43m (compared with a $70m net profit in 2002).

Total passengers carried in 2003 fell 4.8% to 20.5m. While international RPKs fell by 25.2% in 2003 compared with 2002, domestic RPKs were down just 3.6% in 2003.

Overall, RPKs rose by 8.8% and ASKs fell by 7.6%, with load factors declining by 0.8 percentage points to 64.6% in 2003.

But recovery has been marked in 2004.

For the first half of the year China Southern reported a 65% rise in revenue, to $1.3bn, and an operating profit of $91m, compared with an operating loss of $166m in the first half of 2003. The net profit totalled $40m, compared with a $140m net loss in 1H 2003.

China Southern operates 114 Boeing and Airbus aircraft, and has 29 more on order.

In April 2004 China Southern ordered 15 A320- 200s and six A319s for $1.2bn, for delivery by the end of 2006. In November 2003 the airline confirmed an order for four A330–200s for new long–haul routes, for delivery from 2005 — the first A330s that Airbus has sold in China. These were part of the 30–strong Airbus order announced by the Chinese government in April of that year.

In September China Southern also announced that it was amending an existing order for 23 leased A319s from ILFC made in 2003 into an order for at least 15 leased A320s instead. The aircraft will arrive by 2007 and replace a fleet of MD–82s and MD–90s at subsidiary China Northern. The first two ERJ- 145s from an order for six of the type arrived at China Southern in June 2004.

The others will be delivered by January 2005, with the 50–seat 145s replacing 737s on domestic routes run by a subsidiary out of Guangzhou.

Though China Southern took out new loans for $255m in 2003 — in order to pay loans due on aircraft financing — by the end of 2003 China Southern had built up a healthy cash pile of $250m.

China Southern appears to have so much cash that in July this year it engaged Centergate Securities, a Beijingbased investment house, to invest $60m on its behalf. It was a decision that many analysts found bizarre (China Southern’s share price fell by 6% in a few hours after the announcement) given that the airline may soon be committing itself to large orders for long–haul aircraft and is investing heavily in relocating its hub to the new Guangzhou Baiyun International airport.

China Southern’s key northern subsidiary, China Xinjiang, has plans to add to its fleet of 24 aircraft by leasing four 757–200s and four 737–700s over the next 12 months.

The aircraft will be used for an expansion of both domestic operations and international routes into central Asia.

Other international moves include code–sharing with Dragonair on Guangzhou–Hong Kong from December 2003, and code–sharing is also planned with Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) — China Southern currently operates between Kashi and Urumqi (in northwest China) and Islamabad. China Southern is also the only one of the Big Three to operate to the Middle East — it operates Beijing–Dubai and Beijing–Sharjah services, both via Urumqi in northwest China, and in June 2004 added a Guangzhou–Beijing- Dubai route.

China Southern is expected to join SkyTeam in 2005 or 2006, after signing a preliminary agreement to join in August — the first of the Big Three to make an alliance commitment.

China Southern has close ties with SkyTeam members already, code–sharing with Korean Air and Air France.

China Eastern

Like its rivals, Shanghai–based China Eastern was hit hard by SARS but by August 2003 domestic RPKs were up 64% year–on–year, though recovery of international RPKs took several more months.

For overall 2003 China Eastern saw a 6% increase in passengers carried to 12.2m. Overall RPKs rose 0.3% compared with 2002, but with ASKs rising by 7.8%, load factor fell by 4.5 percentage points to 60.6%. However, while domestic RPKs rose 24% year–on–year, international RPKS fell by 23%. This contributed to a net loss of $115m in 2003, compared with a $10m net profit in 2002. Revenue grew 9.2% to $1.7bn in 2003, while operating profit fell from $101m in 2002 to $24m in 2003.

In January–June 2004 China Eastern recorded its highest ever net profit since listing in 1997, with $57.9m in net profit compared with a $150m net loss in the SARS–hit first half of 2003. Revenue rose 69% to $1.1bn. Return on net assets was 9.9% in the half year, compared with a -27.1% return in 1H 2003. Passengers carried rose 57% in the period, to 13.3m, and the growth is continuing through the second half, with August traffic up 21.4% year on year. However, for the full year China Eastern is warning that its costs will rise considerably due to higher fuel prices and aircraft leasing fees.

The turnaround in finances will help China Eastern reduce long–term debt of $1.4bn as at the end of 2003 (compared with $0.7bn a year earlier). In May 2004 the airline raised $90m to "alleviate its capital deficiency" by selling and leasing back 24 engines to an undisclosed party.

Perhaps of more pressing concern to China Eastern is the Chinese government’s announcement that from 2005 it is opening up Shanghai’s two airports to all domestic air–lines, without restriction.

This decision reversed a 2002 decree that prohibited airlines not based at Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou from operating to those destinations (a move designed to overcome "disorderly competition"), and which also placed restrictions on flights from those cities to secondary destinations. The latest move is believed to be an experiment to see how liberalisation affects traffic to and from a major city, and if successful the government may open up some or all of China’s other major cities. But while good for the industry as a whole, it’s not such good news for China Eastern and the other local carrier, Shanghai Airlines.

Partly as reaction to this, China Eastern is pressing ahead with the full integration of profitable domestic airlines China Northwest and Yunnan Airlines into its operations, which is part of the Chinese government’s industry consolidation plan. The two carrier’s are helping boost China Eastern’s fleet, which currently stands at 144 aircraft, with 16 737NGs and A320 family aircraft on firm order.

The airline plans to increase the fleet to 209 by the end of 2005 and at least 250 by 2010.

In June China Eastern signed an MoU for 20 A330- 300s (via the government’s China Aviation Supplies Import & Export Group), for delivery from the first quarter of 2006 onwards.

If confirmed, the aircraft will be used to replace A300–600Rs on domestic and international routes, and to provide new capacity — originally China Eastern was going to order 10 aircraft, but doubled its order at the last moment.

On cargo, the last of China Eastern’s MD- 11s were converted into freighters earlier in 2004 and passed on to subsidiary China Cargo Airlines. China Eastern owns 70% of China Cargo (with China Ocean Shipping owning the other 30%) but it has been planning to sell 10% of its stake to Taiwan’s China Airlines ever since 2001. Not surprisingly, this has been delayed as it is a politically sensitive deal, though China Eastern is still pushing hard for completion as it plans to use the proceeds to pay down some of its debt. China Eastern also launched an FFP tie–up with China Airlines, the Taiwanese flag carrier on October 1st, and this could lead to code–sharing in the future.

China Eastern’s aggressive fleet expansion will underpin a large increase in both its domestic and international network in the next couple of years. In April China Eastern started services from Shanghai to London Heathrow, becoming the second Chinese airline to serve the UK (after Air China). The route was to have been started a year previously, but was delayed because of SARS.

China Eastern is also planning major expansion on routes to Japan. A Beijing–Yantai- Osaka route was launched in November 2003, followed by a Kunming–Osaka service the following month. Further routes to Osaka and Tokyo are under consideration.

A Shanghai–Kuala Lumpur service started in January 2004. China Eastern also started a service between Shanghai and Melbourne in December 2003, the last of the Big Three to serve the destination.

China Eastern is likely to join oneworld sooner rather than later. It already has close ties with oneworld’s Cathay: they became FFP partners in 2001 and under a joint training deal 40 China Eastern flight attendants are carrying out 18–month secondments at Cathay in order to improve their service skills.

Cathay restarted flights to China at the end of 2003 after being granted an operating licence by CAAC. However, despite a revised bilateral between Hong Kong and mainland China in September 2004 that allows a 30% increase in flights between the regions, Cathay is blocked from operating on the lucrative route to Shanghai until October 2006, which is likely to lead to a code–share deal between Cathay and China Eastern.

The independents

The implicit pressure from the Chinese government on the independents to "align" themselves with one of the Big Three remains, with only large surviving independents being Shanghai Airlines and Hainan Airlines.

Shanghai Airlines has a 35–strong, all but four of which are Boeing aircraft. After net profits fell 35% in 2003 to $11.1m, it reported a half–year 2004 net profit of $17.5m (compared with a $24m net loss in 1H 2003).

In September 2004 the carrier announced it was acquiring Beijing–based China United Airlines for $8.5m. China United is run by the Chinese air force and operates domestic and international routes with a fleet of 15 737s and Russian aircraft. The acquisition implies Shanghai has realised that it needs to copy the acquisitive strategy of the other remaining large independent, Hainan Airlines, if it wants to avoid being swallowed up by the Big Three and survive the challenge of the opening up of Shanghai’s two airports to domestic competitors.

Hainan Airlines operates 65 aircraft, the majority of which are again Boeing models. However, it has 31 aircraft on order as it expands its way to survival against the Big Three. In 2003 it racked up a massive net loss, of $153m, though in 1H 2004 net profit of $10.4m was recorded, compared with a net loss of $118m in January–June 2003.

Hainan’s latest move is the planned launch of Shilin Airlines in Yunnan, in the southwest of China, with a fleet of at least five regional aircraft. Hainan launched a route to Osaka in September and has also applied for permission to launch a service to New York.

Yet despite the consolidation of the last few years, there are tentative signs that Chinese government may be prepared to allow new private airlines to emerge.

In May, a licence was awarded to Yinglian Eagle United Airlines, which is owned by a Guangdong telecoms company and which plans to start regional routes from Chengdu sometime in 2005. Additionally, in June preliminary CAAC licences were given to two further start–ups — Shanghai–based Spring Autumn Airlines and Tianjin–based Aokai (now renamed Okay Airways).

Yinglian claims it will be a LCC, as does Okay, but whether the Chinese government will allow budget carriers to emerge and compete against the domestic networks of the Big Three will be the true test of liberalisation.

Malaysian LCC AirAsia is planning to launch a route between Bangkok and Kunming (in the south west of China) in December 2004, and the CAAC will be keeping a close watch on how successful the LCC is. There are certainly enough secondary airports around to make LCC routes viable in theory, but after consolidating a mess of Chinese airlines into three large groups, there may be reluctance by some in the government to let entrepreneurial airlines attack the Big Three — particularly before Air China has completed what may be a tricky IPO.

| 737- | 737- | 737NG | 747- | 747- | 757 | 767 | 777 | A300/3 | A320 | A330 | A340 | MD1 | MD8 | MD9 | Rus | Chi | Other | Total | ||

| 2/300 | 4/500 | 2/300 | 400 | 10 | fam | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Air China | 34 | 25 (12) | 12 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 14 (6) | 6 | 4 | 132 | (18) | |||||||||

| Air China Cargo | 4 | 1 (2) | 5 (2) | |||||||||||||||||

| Air Hong Kong | 1 | (6) | 1 (6) | |||||||||||||||||

| Air Macau | 2 | 11 | 2 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cathay Pacific | 6 | 24 (1) | 15 (2) | 23 (3) | 18 | 86 | (6) | |||||||||||||

| Changan AL | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| China Cargo AL | 6 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| China Eastern AL | 12 | 13 (7) | 16 | 63 (9) | 10 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 144 | (16) | |||||||||

| Flying Dragon AV | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| China Northern AL | 6 | 11 (15) | 15 | 10 | 4 | 46 (15) | ||||||||||||||

| Northern Swan AL | 4 | 3 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| China Postal AL | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| China Southern AL | 28 | 12 | 16 (4) | 2 | 20 | 10 | 24 (21) | (4) | 2 | 114 | (29) | |||||||||

| China United AL | 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| China Xinhua AL | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| China Xinjiang AL | 2 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 24 | ||||||||||||||

| CR Airways | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dragonair | 4 | 16 (1) | 10 (6) | 30 | (7) | |||||||||||||||

| Guizhou AL | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hainan AL | 6 | 7 | 20 (11) | 5 | 27 (20) | 65 (31) | ||||||||||||||

| Shandong AL | 11 | (7) | 11 | 22 | (7) | |||||||||||||||

| Shanghai AL | 1 | 14 | 11 (3) | 5 | 4 | 35 | (3) | |||||||||||||

| Shenzhen AL | 7 | 18 (5) | 25 | (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Sichuan AL | /P> | 13 (5) | 5 | 18 | (5) | |||||||||||||||

| Xiamen AL | 4 | 6 | 10 (5) | 8 (1) | 28 | (6) | ||||||||||||||

| Yangtze Express | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yunnan AL | 13 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 26 | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 137 | 28 | 128 (51) | 15 | 39 (3) | 61 (4) | 27 | 35 (2) | 24 (6) | 152 (57) | 33 (13) | 34 | 6 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 2 | 82 (20) | 869 (156) | |