Frontier: another LCC model, another success

October 2003

In recent months several US low–cost carriers have successfully raised funds through secondary public share offerings. Most recently, Frontier and AirTran raised about $81m and $132m respectively by that method in late September, following JetBlue’s $122.

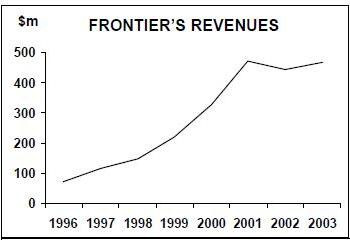

4m secondary offering in July. While JetBlue and AirTran certainly seem poised for exciting and profitable growth (see Aviation Strategy briefings, July/August 2003 and April 2003), will Frontier live up to the investors' expectations? Denver–based Frontier is the smallest of the three, with annual revenues of $470m in its latest fiscal year ended March 31, 2003, compared to AirTran’s $733m and JetBlue’s $635m in 2002. It shares many characteristics with AirTran — both are early 1990s entrants, operate essentially hub–and–spoke networks and share their main hubs with a major carrier. The latter has had important implications for strategy; for example, pricing in the Southwest model is out of the question — Frontier calls itself an "affordable–fare" airline.

Like AirTran, Frontier has beaten heavy odds in surviving and building a profitable hub operation at Denver (DIA) in head–to–head competition with United. It had a shaky start in 1994 because it was very thinly capitalised and initially chose the wrong markets. 1996 and 1997 were equally challenging years because of United’s "strong arm" pricing tactics and new competition from the former Shuttle in some of the Denver markets, as well as Western Pacific’s move to DIA and subsequent Chapter 11 bankruptcy. All of that meant that the Denver market became saturated with excess capacity at deep–discount prices.

Frontier’s prospects improved dramatically in 1998, following WestPac’s shutdown and a clear signal from Washington to the major carriers that predatory behaviour would not be tolerated. Frontier was able to secure a $14.2m equity infusion in April 1998, which gave it adequate cash reserves for growth. It grabbed the opportunity to re–establish itself with a sound business plan and gradual growth strategy. In the first place, that meant becoming transcontinental, with services to Boston, Baltimore and New York LaGuardia, and focusing more on higher–yield traffic.

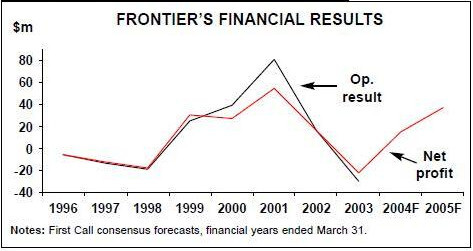

The result was an impressive financial turnaround in 1998/99, and in the subsequent two years Frontier’s profits surged as revenues more than doubled. When its profits peaked in FY 2000/01, the airline had a stunning 17% operating margin — not far off from Southwest’s industry leading 18%.

Under an ambitious programme introduced in May 2001, the airline is replacing its entire fleet of used 737s with brand new A320–family aircraft. As a result of the latest follow–on order in August, Frontier is due to add about 40 more Airbus aircraft in the next 4.5 years. This would mean growing ASMs at a heady 25–30% annual rate, which would be faster than AirTran.

However, unlike JetBlue and AirTran, Frontier has not remained profitable all the way through the post–September 11, 2001 industry crisis. It had a promising start, earning small quarterly profits through the end of March 2002 and a respectable $16.6m net profit for FY 2001/02. But after that there were four consecutive and steadily worsening quarterly losses, culminating in a disastrous $18m operating loss (15% of revenues) in this year’s March quarter. For FY 2002/03, the airline reported a $30.6m operating loss and a $22.8m net loss.

The March quarter losses reflected the worsened industry environment due to the Iraq war, higher fuel prices and aggressive competition from United in the initial months after its Chapter 11 filing in December 2002 — and Frontier has since then returned to marginal profitability. However, the contrast with JetBlue’s and AirTran’s strong operating margins and uncertainty associated with UAL’s bankruptcy has made Frontier look like a riskier investment proposition.

None of that was reflected in the secondary share offering, which was a huge success despite the added complication of further negative news from United. On September 17, two–days after the Frontier offering was first announced, UAL made the official announcement that it had decided to proceed with a low–cost unit (from February 2004) and that DIA would be the launch hub.

The result? Frontier’s offering was increased in size from 3.7m to 4.7m shares.

The underwriters (led by Morgan Stanley as sole book–running manager, with Merrill Lynch and Raymond James as co–managers) elected to purchase 350,000 extra shares, representing half of their increased over–allotment option. The offering was priced at $17, at a mere 4% discount to the previous day’s closing price. Frontier collected $81.1m in net proceeds.

The offering was a success; in the first place, because analysts considered the 2002/03 financial losses as temporary, predicting strong profit growth in the immediate future and continuing to recommend Frontier shares as a "buy".

Also, Frontier intended to use 60% of the proceeds to prepay most of its recent government- guaranteed loan several years early, rather than just for working capital. Investors must also have noted that, by granting Frontier the government–guaranteed loan in the first place, the ATSB was obviously convinced that the airline had a sustainable business model.

Frontier returned to profitability in the June quarter — one quarter ahead of expectations.

The net profit amounted to only a marginal $2.1m or 7 cents per share before special items, but recent revenue and cost trends have been encouraging. In late September the First Call consensus forecast was a net profit before special items of 50 cents per share in the current year and $1.25 in FY 2004/05 — about $15m and $37.5m respectively, compared to last year’s loss of $22.8m.

Revenue improvements

The revenue situation has improved dramatically since the March quarter, when United’s aggressive pricing resulted in a collapse of unit revenues in the Denver markets.

Frontier’s average fare had plummeted by 15.6% and RASM by 17.1%, compared to an industry RASM decline of 3.5%. Although average fares and unit revenues have remained at low levels, in recent months Frontier has seen a surge in total revenues resulting from dramatic load factor improvements.

In June, July and August its average load factor rose by 11, 15.4 and 17.2 percentage points respectively, from low–mid 60s to high–70s.

The improvements were attributed, first, to United having retrenched from its earlier aggressive price–matching policies. Second, like other US airlines, Frontier was able to raise its fares by $5 in the early summer as a result of the temporary suspension of the government- imposed security fees (which, unfortunately, were reinstated on October 1).

Third, and most significantly, Frontier is benefiting from a new simplified fare structure that it boldly introduced in the spring. The move essentially involved reducing its highest- level business fares by up to 44%, cutting its lowest available walk–up fares by up to 68% and capping one–way fares at $499.

For example, on the San Francisco–Baltimore route, the new fare range is $139-$499, compared to $199-$788 previously.

It is worth noting that every effort by the US major carriers to change their fare structures in recent years has failed miserably. So it is impressive that Frontier can accomplish something like this — attracting more business travellers through fare changes evidently without provoking competitors.

The airline also attributed the revenue improvements to increased frequencies in key markets and a new branding campaign called "A Whole Different Animal" launched in May. The campaign includes TV, radio and print ads featuring the attractive animal artwork on Frontier’s aircraft tails. It emphasises a commitment to being "affordable, flexible, accommodating and comfortable" and spotlights the key attributes of a nationwide network, new Airbus fleet and LiveTV.

Frontier is the first and so far the only US airline that JetBlue has allowed to buy its LiveTV product, which features 24–channel satellite TV at every seat. The Denver–centred network means that it is not regarded as a direct competitor. Since signing the deal in October 2002, Frontier has now completed its installation on all A319s and A318s. The product is expensive, but the airline collects a $5usage charge per flight segment. LiveTV may prove extremely helpful to Frontier in terms of differentiating its product.

Benefits of fleet renewal

Last year Frontier succeeded in reducing its unit costs by 10.8%, from 9.33 to 8.32 cents per ASM. Ex–fuel CASM fell by 13.8%. This was among the industry’s best unit cost performances.

The management attributed it primarily to savings from the new Airbus fleet, as well as higher aircraft utilisation and an increased percentage of owned (as opposed to leased) aircraft.

However, the savings from the Airbus fleet have been mitigated by significant return expenses associated with the 737s — mainly increased maintenance, such as C–checks, to meet specific return standards for the leased aircraft. The fleet transition benefits will not be fully realised until all of the 737s are out, which is scheduled to be by September 30, 2005. In Raymond James analyst James Parker’s estimates, Frontier may by then have reduced its CASM to 7.5 cents.

At the beginning of October Frontier’s fleet consisted of 39 aircraft — 15 737s and 24 A319/A318s. Six months from now, at the end of March 2004, the fleet size will still be 39, though the composition will have changed to 11 737–300s and 28 Airbus aircraft, including 24 132–seat A319s and four 114–seat A318s.

The current year is seeing a temporary reduction in ASM growth, to about 17.5% from last year’s 31%, as there will only be two net aircraft additions (much of the growth will evidently be achieved through increased aircraft utilisation).Next year will see ASM growth accelerated to about 27%, facilitated by a new Airbus order in August.

Frontier confirmed an earlier LoI to purchase 15 more A319s and lease 14 more A319s, for delivery over the next five years. This will bring its Airbus fleet to 62 aircraft by March 2008, including 55 A319s and seven A318s. The deal also granted purchase rights for 23 additional A319s or A320s from FY 2005/06.

So far at least, the strategy seems to be to purchase about half of the new aircraft and take the other half on operating leases. The current outstanding commitment to buy 17 Airbus aircraft represents a $561.7m funding requirement (including spare parts, LiveTV, etc) over the next 4.5 years.

Stronger balance sheet

Frontier applied for government guarantees on a $70m credit line just two days before the late–June 2002 deadline, saying that it felt compelled to take that step after UAL applied for loan guarantees of nearly $2bn (the latter application is still pending, likely to be used as Chapter 11 exit funding).

However, Frontier actually needed the money, because losses in the second half of 2002 had depleted its usual $100m–plus cash reserves to $31.5m at year end and the first quarter of 2003 was shaping out to be a financial disaster.

Thanks to the ATSB loan, Frontier’s cash reserves recovered to $104.9m at the end of March 2003. Improved operating results and a security fee reimbursement from the government subsequently raised the cash balance to $128.3m at the end of June.The company received a $26.6m tax refund in July but, as required by its loan agreement with the ATSB,used $10m of that to reduce the $70m outstanding under the loan. After using 60% of the share offering proceeds to further pay down the loan, Frontier expected to have just $11- 12m outstanding on the ATSB loan.

Under the original schedule, quarterly principal payments were due to begin in September 2004 and there would have been a final $33m balloon payment due in June 2007.

Now the balloon payment has been eliminated and Frontier will have six relatively small principal payments between September 2004 and March 2006.

All of this has helped restore Frontier’s balance sheet, which has seen a substantial build–up of debt over the past two years as a result of the Airbus purchases. Long–term debt rose to $261.7m at the end of March 2003 from just $204,000 two years earlier, while stockholders' equity improved only marginally, from $144.8m to $159m, in that period.Pro–forma figures for June 30 show that, as a result of the share offering, long–term debt declined from $258.8m to $213.5m and stockholders' equity rose from $170.8m to $246.2m. In one analyst’s estimate, the lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio improved from 83% to 75%.

Route network strategy

Because of Denver’s great geographical location and large local market, Frontier was able to develop a nationwide route network earlier than other low–cost carriers. It serves a large number of key cities on both coasts, as well as some now in Mexico. It also considers RJ operations an important part of its business model, using affiliates to serve many smaller cities as Frontier JetExpress.

Frontier is continuing a "disciplined growth strategy", introducing new service as demand dictates and opportunities arise. The latest city additions are Orange County (California) and Milwaukee (Wisconsin). St. Louis will be added in November, followed by three new destinations in Mexico. As a significant development on the regional service front, last month Frontier signed up Alaska Air Group’s Horizon Air as a new RJ partner. This will replace an expiring smaller–scale code–share arrangement with Mesa, which recently joined the United camp. Horizon will operate up to nine 70–seat CRJ–700s for Frontier from January 1. The 12- year agreement appears to be structured like a standard fixed–fee agreement between a major carrier and its feeder partner, with Frontier controlling the schedule and destinations and paying Horizon a base margin and performance–based incentives.

UAL uncertainty

The biggest risk for Frontier is that United could become a more aggressive competitor at DIA, where it is the dominant carrier with a 61% passenger share. The risk is magnified at present because of all the uncertainty surrounding the major carrier’s bankruptcy.

If things go badly for UAL, will it start cutting fares and dumping capacity, pushing also Frontier back to losses? If things go well, will United simply become a more formidable competitor? On the other hand, United could continue cutting capacity, which might lead to some recovery in average fares and further market share gains for Frontier at DIA. In the first seven months of this year, Frontier improved its DIA market share by 28% to 13.6% as it continued to add capacity while United was cutting back. United’s shrinkage could also give Frontier the extra gates that it is seeking.

But even United’s shrinkage at DIA is not necessarily good news for Frontier. If United rejects a significant portion of its payment obligations to DIA or substantially reduces operations there, the resulting decline in revenues to the airport would proportionally raise costs for other airlines. As things stand, DIA is already one of the nation’s most expensive hubs to operate from.

United’s decision to launch its low–fare, low cost operation (currently only referred to as "LCO") from Denver in February, initially with four A320s but expanding to 40 by the end of next year, is obviously not good news for Frontier. However, it is hard to see the low–cost carrier being severely impacted.

First, there is considerable scepticism that the proposed venture would work, given other majors' failed attempts to launch low–cost units. Second, it is not expected to add to DIA capacity; rather, it would replace existing United service in markets where the major already largely matches Frontier’s fares.