FedEx: official airline of the Internet?

October 1999

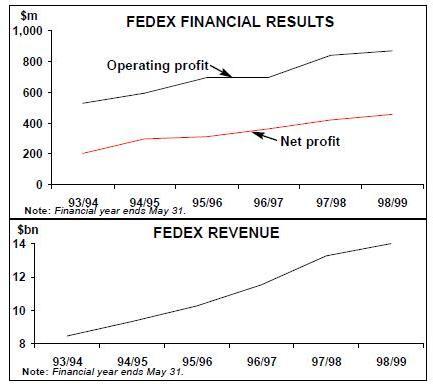

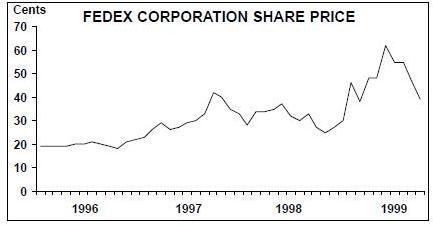

Over the past 12 months FedEx’s stock price movement has resembled that of a volatile Internet stock rather that of an established cargo airline. Indeed, until recently, certain US equity analysts have promoted FedEx as the safe way to play the stock market’s obsessional affair with new technology stocks.

Shares in FedEx tripled in value from May 1998 to May 1999, but have since fallen by 40%. A profits warning was issued in September quoting two factors — rising fuel costs and a disappointing volume growth (3%) in US traffic for the three months to August 1999 as a result of customers running down their inventories. At the same time there are clear indications that faith in Internet stocks, with their inflated stock–market valuation based entirely on future cashflow expectations, is beginning to evaporate.

But why was FedEx considered as a quasi- Internet stock in the first place? Although the analysts highlighted FedEx’s internet connections last year, the concept dates back to 1996 at least when Wired, the magazine for new technology entrepreneurs and their venture capitalists, labelled FedEx as “the official airline of the Internet”.

It seemed that FedEx was set to repeat the phenomenal growth it achieved in the late 1970s and 1980s when its management under Fred Smith recognised a key change in the demand for express freight. Consequently the airline was positioned not only to fulfil that demand, but also to help fuel it. Companies increasingly needed to replace large, expensive, physical inventories with virtual inventories; in other words, they needed to be sure that packages of spares, documents etc would be delivered overnight with total reliability.

FedEx’s marketing therefore emphasised the importance of the data attached to each shipment. Its proprietary online network, Cosmos, was able to track the status of every packet in the FedEx system and communicate this information to customers, or rather the 60% of customers who were able and/or willing to use FedEx’s hardware and software. Then came the Internet and, in 1994, FedEx’s website — www.fedex.com — not particularly remarkable now but, a mere five years ago, almost revolutionary in that it allowed potentially 100% of FedEx’s customers to book and pay for its services electronically.

In April this year FedEx announced a joint venture with Netscape, a subsidiary of America Online Inc., to create an Internet package portal. The aim is to simplify e–commerce transactions and to offer online purchasers personalised package status tracking. FedEx is the pre–selected carrier for all e–commerce transactions on Netscape Store, apparently a confirmation of FedEx’s position as the Internet’s official airline.

To those attuned to the e–commerce revolution it seemed that FedEx was uniquely positioned to take advantage of all the changes taking place in consumer behaviour and business- to–business activity. To quote from the seminal Wired article: “FedEx’s vision of the future is a digital marketplace of cyberspace superstores, operated by managers who need only worry about marketing, customer service and counting the cash as it comes in. FedEx promises to make all the pieces fit together and do all the heavy lifting in terms of invoicing, inventory management, order fulfilment and product shipping. The payoff will come by pumping more packages through FedEx’s network and by skimming a few percentage points off the value of its transaction in exchange for providing the software and systems integration that makes it all happen.”

Internet hype?

However, reality hasn’t quite conformed to this cyber–vision.

First, the e–commerce market has two different market segments — business–to–business trade (b–to–b) and business–to–customer trade (b–to–c). In the b–to–c segment there is not necessarily a connection between e–commerce and express delivery. For example, a person ordering a book or compact disk through the Internet from, say, Amazon.com, will normally have the purchase delivered by snail mail, otherwise the delivery cost would probably be more than the cost of the book itself.

Nevertheless, the b–to–b segment (electronics, computer software and hardware, automotive parts, etc) is expected to grow significantly more rapidly than the b–to–c trade. In Europe, for example, TNT estimates that the b–to–b trade is expected to grow in Europe eight times faster than b–to–c, and is expected by 2001 to total nearly US$60bn, while the b–to–c market will reach just US$8bn. For the integrators it is the faster growing b–to–b market which is likely to provide the major growth opportunities

Second, in the short–term at least the growth of electronic communication must be having a negative effect on the volume of documents carried by express operators (although they point out that e–mail affects fax transmissions more than urgent letters). This decline will probably accelerate as legally binding electronic signatures become more widely accepted.

Third, FedEx has been facing intense competition not only from its big, conservative and highly efficient rival, UPS, (which has about 30% of the domestic US market compared with FedEx’s 43%) but also from improved services being offered by scheduled airlines and freight forwarders, often in collaboration.

Fourth, FedEx has been impacted by Stage 3/Chapter 3 noise legislation which has required 727 fleets to be hush–kitted and caused accelerated investment in new or converted A300 types.

Fifth, competition between the integrators has moved to a global stage, but outside their domestic market the US giants often appear to be unclear about their strategies.

FedEx entered the Asian market back in 1985 and set up a hub in Taiwan. The acquisition in 1989 of Flying Tigers, which served 21 Asian markets, should have served to consolidate FedEx’s position. However, wrangles between FedEx, the Taiwanese government and local freight forwarders forced it to downsize its Taipei operations. In 1995, FedEx chose Subic Bay near Manila in the Philippines as its Asian super–hub.

UPS did not arrive in Asia until 1988 when it acquired the Hong Kong carrier, Asian Courier Systems. It has apparently been able to overcome Taiwanese political issues more successfully than rival FedEx, and in 1997 opened its regional hub at Chiang Kai–Shek International Airport. Taiwan’s geographic position is much closer to that of the main Asian commercial centres than Subic Bay, and this should provide UPS with an advantage.

FedEx’s first foray into Europe was an unmitigated failure. In 1992 it was forced to pull out of Europe’s domestic and cross–border parcel market to concentrate solely on intercontinental traffic. The company cited an immature market with too many low–cost, low–tech operators for its decision. Now it has returned to the market with a hub at CDG, Paris, and has recently won extensive fifth freedom rights at Prestwick Airport in Scotland that will enable it to further develop this transatlantic hub.

Strong European competition

But in Europe, DHL, TNT and UPS are in stronger positions. DHL enjoys pre–eminence in the European express market with a market share in excess of 40%. TNT is the second largest player with a market share of some 15%. UPS first entered the European arena in 1976, setting up its regional hub in Cologne, Germany, 10 years later. Ranked a close third behind TNT in Europe, UPS has set itself the goal of catching and surpassing DHL. FedEx probably has less than 5% of the market.

A key characteristic of the European market is the links between TNT and KPN (the Dutch Post Office) and between DHL and Deutsche Post in Germany. These allow the post offices to combine their national parcel networks with the international delivery systems developed by the integrators. The post offices have strong cash flow but a relatively mature business; the integrators require cash to upgrade their systems and aircraft fleets and offer growth rates that historically have averaged some 20% a year. Both the mail and express businesses are largely driven by scale. Given that both mail and express require high fixed–cost networks, success depends on the ability to attract high volumes to ensure that network capacity is used as efficiently as possible.

This structure provides a formidable barrier to entry for the US integrators, one that UPS is challenging in the courts. UPS is arguing that profits from Deutsche Post’s domestic monopoly are illegally subsidising the express services to/from Germany.

For UPS and FedEx, breaking down these institutional barriers is a prerequisite to industry consolidation (UPS is rumoured to be planning to use part of its upcoming $3bn IPO to launch a bid for TNT). Then they can begin to exploit the e–commerce potential of Europe, which is probably 3–4 years behind the US.