British Midland's search for a global alliance

October 1999

British Midland has suddenly shed its low profile, is actively seeking out a membership of a global alliance (and may be enquiring about future equity investments), and has instigated an advertising campaign attacking what it regards as excessive transatlantic business fares charged by, in particular, British Airways. Why the change?

Recent developments appear to be a little out of character for Sir Michael Bishop, the chairman and chief executive, who has a reputation for caution and pragmatism. British Midland has never bought widebodies (though it has options on two 767–300s and two A330–200s for Spring 2000 delivery), has only relatively recently put major emphasis on continental European expansion, and has been competitive rather than aggressive in terms of pricing.

Unlike Virgin, BMA did not oppose the BA/AA alliance. Rather Bishop has appeared sceptical about the benefits of global alliances, although he has been an arch–exponent of code–share agreements signed with multiple partners — 18 currently.

However, the company’s core strategy is clear: building up its slot position at Heathrow to the extent that it now controls around 1,100 weekly slots, 14% of the total. The value of the company is totally bound up with the value of these slots.

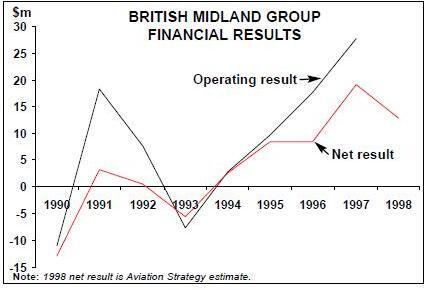

Although it is assumed that their value can only rise, it is worth pointing out that BMA has not extracted much profit from the Heathrow slots. Its 1998 results showed a pre–tax profit of £11m ($18m) on revenues of £561m ($926), the margin of 2% being the second highest achieved during the 1990s. BMA’s results, in fact, are quite similar to those produced by British Airways on its intra- European and domestic network.

Converting some of these slots from intra- European to transatlantic would greatly enhance their earning potential, and this consideration undoubtedly lay behind BMA’s recent attempts to re–instigate transatlantic service (it did fly 707 charters to the US in the 70s). In February 1998 it applied for 10 licences from London–Heathrow to US cities and was granted New York, Washington, Boston, Miami but failed to get Atlanta, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles and Seattle.

In retrospect though, Bishop misread US–UK open skies progress, and has been totally frustrated by the collapse of the talks in July. BMA is now concentrating on Manchester (which lies outside Bermuda 2 bilateral and which has no slot constraints), having applied in January 1999 for licences to Boston, New York, Los Angeles and Washington. These have now been followed by new applications for licences from Manchester to Atlanta, Chicago, Cincinnati, Houston, Miami and Seattle.

The transatlantic influence

Entering into a global alliance is inextricably linked with the transatlantic strategy for various reasons.

First, BMA was advised by US DoT that in order to get approval to fly to the US it would have to give up its code–share with American, as otherwise it would not be seen as increasing competition. In any case, the American relationship had been deteriorating since the formation of one world. That code–share will now end in March 2000, and the others will have eventually to be dismantled as strategic alliances demand exclusivity.

Second, to cover the investment cost of transatlantic operation BMA would probably need financial support from larger airlines, and it would certainly require US feed and block space agreements from a large US domestic carrier.

Third, BMA is not a low cost airline, and its route structure may well be vulnerable to the new entrants. Through the transatlantic/global alliance strategy, BMA would be reducing its exposure to the low cost airlines as well as gaining marketing benefits through, for instance, full access to a global FFP.

Fourth, at some point in the future Bishop and his two partners in BBW, which owns 60% of BMA, will probably want to cash in their shares, either through a flotation or a trade sale, and their shares would normally be more highly valued if BMA were an integral part of one of the global alliances.

Bishop has categorically denied that the airline is for sale at present but it is likely that potential alliance partners have been asked to submit wide–ranging proposals, which could include expressions of interest in future equity participation. Complicating the question of investment in BMA is, of course, SAS’s 40% share acquired in two tranches in 1988 and 1994.

Although the two airlines do not talk openly about their shareholders’ agreement, Aviation Strategy understands that certain key clauses include the following:

- SAS is considered to be the main provider of further equity capital for BMA;

- BMA’s current slot allocation at Heathrow cannot be voluntarily reduced;

- If Bishop ceases to be a director then SAS has an option to increase its stake to majority ownership;

- Confidential financial and strategic information about BMA may not be passed on from SAS’s representatives at BMA to SAS or other airlines;

- The sale of shares in BMA to another airline requires SAS’s consent;

- However, if BBW or one of the partners in BBW wants to sell shares to a third party, SAS has to be given the opportunity to place a competing bid to buy enough shares (roughly 10% of the total) in order to give it majority ownership of the company; and

- The price that SAS would have to pay to gain 50%-plus of the shares may be determined by an independent valuation of the whole airline by a merchant bank or auditor.

So it would appear that BMA’s management is significantly constrained as far as selling its stake to an airline in an alliance other than Star is concerned. But it could still enter into a rival alliance and operate within that alliance regardless of the SAS stake. Indeed, SAS would appear to have realised few synergies from its investment in BMA, and its two directors on BMA’s board are limited in their ability to influence the airline’s direction. And if BMA were to opt for another alliance, then SAS would probably sooner or later chose to cash in on its investment — in the same way as Swissair, Delta and Singapore Airlines are now all clearing out their residual holdings in each other.

Against this background what are the relative merits of the various alliances for BMA?

- Virgin Atlantic Richard Branson has offered to take over BMA and appoint Bishop as chairman of combined grouping. This would increase Virgin’s supply of Heathrow slots, and give BMA a long–haul partner. A combined BMA/Virgin Atlantic airline would be an attractive flotation, but this option looks unlikely because Bishop is focusing on the established global alliances.

- Oneworld No way; the EC and MMC would see to that.

- Qualiflyer SAirGroup would provide good ancillary savings through Nuance/Gate Gourmet etc. and particularly ground handling through Swissport. But this grouping is not global and there would be no US feed. Also, BMA has historically been at loggerheads with Swissair over access to the Swiss market.

- Wings Northwest and Continental could deliver US feed. But BMA would not accept being assimilated into the new KLM/Alitalia virtual airline, and there would be conflicts with Buzz, the new low cost subsidiary formed out of KLMuk.

- Air France/Delta Delta would be a good source of US domestic feed and the US airline would underwrite BMA’s transatlantic ambitions. There would be expansion possibilities at CDG. And, following their failure to capture Austrian, Air France and Delta would likely be the most generous in terms of future monetary transactions.

- Star United already serves Heathrow, so this alliance could fit in with BMA’s transatlantic plans. Frankfurt would be a good hub for BMA, located sufficiently far from London. The Lufthansa and BMA European networks could be melded together. Finally, SAS’s 40% stake makes Star the favourite alliance ahead of Delta/Air France.