American: Creating returns

for stakeholders

November 2016

American Airlines Group (AAG), the world’s largest airline by traffic, has accomplished some impressive feats in the three years since the closing of the AMR-US Airways merger and AMR’s exit from Chapter 11 in December 2013.

First, it took the new American less than a year to close the profit gap with Delta and United; for a brief period, American even reported higher operating margins than its peers (albeit because of its lack of fuel hedges and profit sharing).

Second, American has passed the tough merger integration hurdles on schedule and largely without a hitch. After combining the two FFPs in early 2015, in July-October last year American moved to a single reservations system. It was a smooth and successful cutover, contrasting with the highly disruptive event that United Continental experienced in 2012 (apparently the trick was to do it over 90 days, rather than on a single day).

Last month (October 1), American completed flawlessly the key flight operating system (FOS) integration — an extremely complicated undertaking that has led to operational disruptions at other airlines. Being able to freely schedule pilots and aircraft across the combined network is crucial for unlocking the full potential of the merger.

Third, American has already reached new joint agreements with all of its work groups, bringing everyone on new pay scales — a process that has often dragged on in other mergers. Having the deals done will boost morale. It also means that large cost increases are now behind American while many of its peers will continue to face significant labour cost pressures in 2017.

The early labour deals were possible because American’s management recognised that, in light of the history of contentious labour relations at both AMR and US Airways, the only way to clinch joint contracts would be to build trust and restore pay rates.

In March 2016, in a major policy reversal, American’s leadership also unilaterally instituted a profit-sharing programme, retrospective to January 2016, which will pay employees 5% of the company’s pretax profit before special items, starting in early 2017. It brought the carrier in line with Delta, United and Southwest, though American’s unions had not asked for it.

The management has also made some extraordinary special gestures. In 2015 CEO Doug Parker gave up his salary, opting instead to be paid only in stock. And earlier this year he gave up his contract (and associated benefits and protections) and switched to working on the same “at will” basis as the airline’s employees. “Nothing about having a contract felt like a shared commitment to working together”, Parker wrote in a letter to employees.

All of those moves were aimed at mending labour relations and achieving a good employee culture, which is critical for a service-oriented company, especially a global carrier seeking to capture premium traffic (something many airlines still don’t realise).

As another accomplishment, American has dealt effectively with the LCC/ULCC threat in its key domestic markets. In 2015 American was disproportionately affected by incursions into its DFW hub by Spirit and other low-cost operators. It began to match the LCCs on fares. The strategy seems to have worked; American recently noted that LCC competition had eased off, while yields had also benefited from the ending of Southwest’s initial growth spurt at Dallas Love field.

In July American stunned the world with the announcement of new credit card agreements with its AAdvantage partners (Citi, Barclaycard US and Mastercard) that are expected to boost its pretax income by a staggering $1.55bn in the next 2.5 years ($200m in the second half of 2016, $550m in 2017 and $800m in 2018).

Until those deals American was disadvantaged in that many of its competitors (including United and Southwest) had secured lucrative new credit card agreements in recent years. But American made up for the delay by clinching deals not just with one but with two credit card providers (apparently an industry-first). CEO Doug Parker attributed that and the magnitude of the benefit to the combined network being a “powerful draw” for both business partners and customers.

The new American was unusually quick to start returning capital to shareholders after bankruptcy. The airline introduced a $1bn share buyback programme and brought back dividends in July 2014 — just seven months after exiting Chapter 11. As of September 30, American had returned more than $9bn to shareholders in the form of share repurchases and dividends.

American is, of course, noted for its aggressive fleet renewal and significant investment in new aircraft and the product, as it strives to restore itself as “the greatest airline in the world”. Its gross capex ($5.6bn in 2016 and $5bn in 2017, though declining to $4bn in 2018 as a result of A350 order deferrals last summer) is massive compared to Delta’s and United’s, but as a result American has a younger and more efficient fleet than its peers. On the product front, American has become the first US airline to offer premium economy seating internationally — a new class that the carrier will roll out over the next 18-24 months.

On the negative side, the early labour deals have caused American’s costs to soar and profit margins to dip below those of Delta and United. In the third quarter, American’s adjusted operating margin, while an extremely healthy 16.3%, lagged Delta’s by 2.5 points and United’s by half a point. Its adjusted pretax margin of 14% lagged Delta’s by 4.2 points and United’s by 1.7 points.

And the downside of the aggressive use of cash to repurchase stock is that American has had to take on significant additional debt to fund aircraft purchases. The strategy contrasts with Delta’s and United’s focus on debt reduction; those two airlines also have more modest new aircraft order books and acquire used aircraft more frequently.

American’s management feels that increasing leverage is justified, among other things, because of the current availability of extremely low interest rates (3% or less) for long-term aircraft financings. Also, American protects itself by maintaining a strong liquidity position.

But in recent months analysts have begun to comment more on American’s debt levels. Many have suggested that while gearing may not matter in the current environment where revenue trends are improving, were the environment to deteriorate, or RASM trends turn positive (expected by mid-2017), investors would pay more attention to leverage and American’s shares could suffer.

The question many are asking is: Will American start deleveraging its balance sheet in 2017 or 2018, when its fleet renewal programme nears completion? Will it at least start providing financial and balance sheet targets (like Delta does) for profit margins, earnings growth, leverage ratios and suchlike?

That said, there are many reasons to be excited about American’s prospects. While most US airlines’ (including American’s) earnings are likely to decline modestly in 2016 and 2017, American would seem to have especially promising cost cutting and revenue-boosting opportunities, which could boost its profit growth from 2018.

Outperforming in RASM

The easing of LCC competition in the Dallas markets, the ending of Southwest’s initial growth spurt at Dallas Love Field, the recovery in Latin America, and the incremental revenue from the new credit card deal have already led to American outperforming the industry in unit revenues.

In the third quarter, American’s RASM fell by only 2.2% — a much lesser decline than at competitors. American could now be the first US carrier to return to positive RASM growth next year. In an October 31 report, JP Morgan analysts predicted that American will see the highest RASM growth among the US carriers in 2017 (around 2.1%).

Domestically, American will soon benefit from its version of Basic Economy — a product technically trademarked by Delta but now also being introduced by United and American during the first half of 2017. It is basically an unbundled, ULCC-type product. United announced details of its Basic Economy in mid-November. American will follow suit in January, when it plans to start rolling out its new product. American has described it as a "game changer" that will allow it to “meet competitors’ prices without the same amount of dilution”.

JP Morgan analysts see Basic Economy essentially as a “corporate fare increase”, because most corporate contracts prevent employees from booking those fares given the onerous restrictions. The analysts wrote: “Apart from bag fees, we consider Basic Economy to be one of the industry’s most creative revenue concepts of the past decade”.

Internationally, American will see a gradual revenue benefit from the rollout of its Premium Economy cabin, which came out in October on the 787-9s and will be added to the existing 777/A330 long-haul fleet by June 2018. It is American’s version of the type of cabin already offered by a number of Asian and European airlines, and Delta will be joining the fray in 2017. American expects to initially monetise it through its existing “main cabin extra” product until it gets to critical mass. The main impact will be in 2018.

American is benefiting from a robust RASM/yield recovery on US-Latin America routes, to which it has the highest exposure among the US carriers. Latin America was the first region to turn positive with 1.8% PRASM growth in Q3, driven by a 25% improvement in Brazil unit revenues as capacity in that market was rationalised and the Brazilian currency strengthened.

While American sees continued strength in Mexico, it could reap benefits from Latin American recovery for at least a couple of years, as economic growth resumes and accelerates in key markets such as Brazil.

Unfortunately, it looks like the Atlantic has taken over from Latin America as the entity to experience a prolonged slump. Continued capacity growth — especially from LCCs and the MENA carriers, collapse of the British pound and lingering effects from recent terrorist attacks contributed to an 11.2% decline in American’s Atlantic PRASM in Q3. Many see tough conditions continuing through 2017 and 2018, and American is reducing its Atlantic capacity by 6% this winter, with the cuts focusing on markets where it has partners. With about 15% of its consolidated capacity on the Atlantic, American is less exposed to that region than United and Delta (both 21%), though when immunised partners are included the three have broadly similar exposure.

The other problematic entity is the Pacific, where much of American’s growth has focused this year. In the third quarter, American’s PRASM in that region fell by 10.5% as its capacity surged by 28.7%.

Like its peers, American continues to take a disciplined approach to overall capacity growth, which will help in the quest to restore positive unit revenue trends. It currently expects system capacity to increase by only 1% in 2017, compared to this year’s 1.5% growth. Next year domestic capacity is likely to be flat and international up by 3.5%, driven by the annualised impact of this year’s Pacific expansion.

Cost saving opportunities

American was fortunate to secure two key labour deals early in the integration process. New five-year joint collective bargaining agreements with pilots and flight attendants became effective in January 2015. Other groups followed, and American now has agreements in place with all of its contract employees.

Costs have soared as a result of the wage increases. American projects that its mainline ex-fuel CASM will increase by 8-10% in the current quarter, of which six points will be driven by labour agreements. The new deals signed this year will add about two points to next year’s core ex-fuel CASM growth, which would otherwise have been just 2%.

But the good news is that because the key deals were signed early and because the rest of the industry has seen, or is about to see, much labour cost escalation, American now has a relative labour cost advantage over Delta, United and Southwest.

Two years ago, American’s pilot deal provided industry-leading base pay but left total compensation below Delta’s. Now, under the latest agreement being finalised, Delta’s pilot pay will soar even higher. Thanks to a snap-back provision, United’s pilots will see pay automatically increase to that of the highest-paid pilots in the industry. And Southwest is awaiting ratification of tentative agreements with all three major labour groups that grant hefty pay increases.

In addition to the favourable impact of the normalisation of labour expenses, American can achieve more cost savings in 2018 and beyond as a result of eliminating duplicate tasks, processes and excess headcount in certain areas, made possible by the recent FOS integration. Much of the work in 2017 will focus on achieving such cost efficiencies. The workforce reduction will be achieved through voluntary means such as attrition and early retirements.

Network and fleet plans

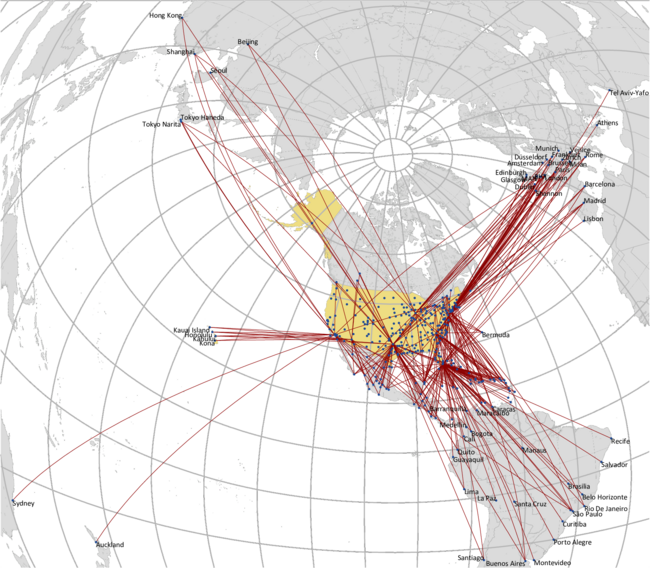

American’s network expansion this year has focused essentially on growing its Los Angeles hub, continuing to add new service to Asia-Pacific and introducing scheduled service to Cuba.

Since the merger, American has more than doubled its Asia-Pacific destinations. This year’s new services have connected Los Angeles with Hong Kong, Tokyo Haneda and Auckland. Following a hot contest with Delta (because US airlines are coming up against the limits of the US-China bilateral), in early November American secured tentative approval to operate Los Angeles-Beijing.

The Asia routes are a natural fit for the 787, which American began taking delivery of in 2015. By year-end American will have received half of the 42 787s it has ordered — seventeen 787-8s and four 787-9s. Its first 787-9 entered international service on the DFW-Madrid and DFW-São Paulo routes in early November.

American began its first scheduled flights to Cuba in September, with service initially to two secondary cities from Miami, and Havana flights are due to follow at the end of November. Having long served Havana with charters, American is determined to be the leading US carrier to Cuba. However, there are still many restrictions in place that make it hard to sell in Cuba; most of the US carriers’ sales are in the US. Making those routes profitable will clearly be a struggle. “We’re in it for the long haul”, CEO Doug Parker stated recently.

American will essentially complete its narrowbody fleet renewal in 2017 with the last A320, 737-800 and ERJ175 deliveries. There will then be a brief pause (of sorts) before the start of the deliveries of the latest-generation aircraft mostly in 2018 or 2019 (the 737 MAX, the A320neo and the A350XWB). At the end of this year, the MD-80 fleet is projected to stand at 57, down from 96 a year ago and 132 in early 2015.

Shift of focus to deleveraging?

At the end of September, American’s total debt and capital leases stood at a $23.6bn, which included current maturities of $1.8bn. However, the top executives continue to insist that they are comfortable with that level for several reasons.

First, American maintains a strong liquidity position, which amounted to $9.2bn in September or about 23% of this year’s revenues. That figure is well in excess of the $6.5bn minimum the company seeks to maintain.

Second, as American’s fleet renewal will be substantially complete in 2017, and assuming that healthy cash flow generation continues, debt ratios will probably start improving from 2018. Some analysts have noted that even as debt increased in recent years, American’s EBITDAR generation was so strong that the leverage metrics remained unchanged.

Third, with liquidity protections in place and the debt levels passing appropriate stress tests against recession, American’s executives feel that it would not be right or in shareholders’ best interest to pass up opportunities to lock in long-term aircraft finance at today’s rock-bottom rates. New aircraft are long-lived assets and good investments. “The right thing is to take debt rather than use cash to pay for aircraft”, the executives noted recently.

Fourth, American feels that the new fleet will give it a significant competitive advantage, both in terms of lower costs and a better product. The new fleet offers “an absolute customer advantage”, and American is well ahead of other US airlines in terms of modernising its fleet.

However, under pressure from analysts, American’s executives have indicated in recent months that they are considering providing long-term guidance and financial targets, which would help the investment community monitor trends and performance.

| Total | 922 | 930 |

| No. of aircraft at end: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sep-16 | Dec 2016E | |

| A319 | 125 | 125 |

| A320 | 51 | 51 |

| A321 | 193 | 199 |

| A330-200 | 15 | 15 |

| A330-300 | 9 | 9 |

| 737-800 | 279 | 284 |

| 757 | 52 | 51 |

| 767-300 | 35 | 31 |

| 777-200 | 47 | 47 |

| 777-300 | 20 | 20 |

| 787-8 | 17 | 17 |

| 787-9 | 1 | 4 |

| E190 | 20 | 20 |

| MD-80 | 58 | 57 |

| Total | 315 | |

| At end of Sep 2016 | Delivery schedule | |

|---|---|---|

| A320 family | 26 | 2016-2017 |

| A320neo | 100 | From 2019† |

| A350 XWB | 22 | From 2018 |

| 737-800 | 25 | 2016-2017 |

| 737 MAX | 100 | From 2017 |

| 787 family | 24 | 2016-2018 |

| ERJ175 | 18 | 2016-2017 |

Note: † Originally from 2017 (deferred in June 2015).

Notes: 2013 revenues are AMR and US Airways combined revenues. 2013 financial results are AMR full-year results plus US Airways results for 22 days in December 2013. 2016E and 2017E are analysts' consensus estimates as of November 21.

Source: Data from JP Morgan's October 31 report on US airlines.