London's airport capacity conundrum

November 2012

The debate on the need for and location transport of additional capacity for London’s air demand has been running for a long time. Those with long memories will recall the Maplin airport debate from the early 1970s, which was killed off by the oil crisis of the period. Fortunately, that oil crisis led to reduced growth in demand. Reduced demand coupled with more intense use of London’s other airports meant that London (still the world’s largest origin and destination market) has continued to cope with its existing airport infrastructure of six major airports. But most accept that the existing system is approaching saturation so the debate on where to provide additional capacity has come alive again with the Davies report due to make its initial findings public at the end of 2013.

Interested parties such as Heathrow Airport are making their views known with a report by Frontier Economics claiming that a lack of capacity is ‘costing’ the UK £14 billion a year in lost trade, a figure that will rise to £26 billion by 2030.

To all intents and purposes, Heathrow is completely full in terms of aircraft movements and Gatwick is close to capacity. However, with the expected growth in passengers per ATM and some infilling of offpeak periods current capacity for London’s airports is estimated to be as illustrated in the table on the right.

| Annual Passenger | 2011 Annual Traffic | |

|---|---|---|

| Airport | Capacity | vs historic peak |

| Heathrow | 86m | 69 m / 69 m |

| Gatwick | 42m | 34 m / 35 m |

| Stansted | 35m | 18 m / 24 m |

| Luton | 18m | 10 m / 10 m |

| City | 8m | 3 m / 3 m |

| Southend | 3m | 0 m / 0 m |

| Total | 192m | 134 m / 139 m |

To meet increased demand, five possible airport development scenarios exist:

A new airport in the Thames Estuary

This is the option preferred by the Mayor of London as it keeps additional capacity away from built up areas with lots of voters. This scheme is also supported by the construction sector due to the scale of the construction projects that would result. The airport would open in the 2030s probably with at least four parallel runways and capacity for at least 120 million passengers.

Demand comes from flights transferred from Heathrow and other London airports. Heathrow is either shut or reduced in operations to a small ‘city’ airport handling no more than 20 million passengers a year. Access to Central London and to the West would be provided by high-speed rail.

A third runway at Heathrow

A third runway built at Heathrow is the option preferred by the airlines, it preserves and enhances the role of Heathrow as a global hub, it minimises costs to airlines and passengers. In economic terms, this option produces the highest returns. There has also been talk of a four-runway airport being the ideal requirement. Whilst this is true, this requirement is a long way in the future at a point at which there is much uncertainty about the nature of this demand and how it should be met.

A second runway at Gatwick

A second runway is built at Gatwick opening in 2025. This option satisfies the demand for additional capacity in the region but is less popular with airlines as the number of connecting flights is limited and most Heathrow airlines do not use Gatwick.

An expansion of Stansted or Luton

An expansion of Stansted is seen by some as an alternate to building a new airport in the Thames Estuary. It is not seen as a viable answer by network airlines due to the airport’s recent experience of falling demand. The other issue for most airlines the lack of feed from a short-haul market due to the entrenched presence of Ryanair and easyJet, which means that the shorthaul market out of Stansted cannot be served profitably by conventional network carriers. The same situation also exists a Luton.

No new runways in the South East

This is preferred option of those concerned about the environmental effects of adding airport capacity. Supporters of thi option suggest that regional airports and high-speed rail can pick up some of the demand. ‘Excess’ demand in the London region can be controlled by increased Air Passenger Duty (taxes paid by the passenger) offset by lower APD rates in the regions.

Questions demanding answers

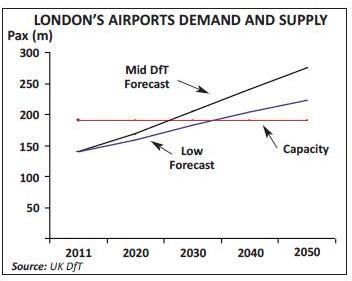

The UK Department for Transport (DfT) does not publish unconstrained forecasts for London, but if one takes the long-term drivers of demand defined by the DfT for the UK as a whole and apply to London traffic (assuming a gradual shift of regional demand from London’s airports to the regions), then a trend demand forecast could be shown as the graph below. The graph assumes fuel and taxation levels increase with an impact equivalent to 1.0% per annum, long-term trend GDP growth of 2.25% and the DfT’s suggested multiplier of 1.3 (declining 0.05 each decade). We also assume that the transfer traffic grows at an equivalent rate to UK origin and destination demand.

The Mid forecast is derived from DfT demand forecasts for the UK as a whole whilst the illustrative Low forecast uses lower GDP and lower multiplier plus a price t effect equivalent to a 1% per annum to produce a substantially lower forecast.

In the Mid case, demand forecasts suggest that the current London system will run out of capacity during the 2020s. Even the illustrative Low case leads to a need for a single new runway during the 2030s. In reality, a perfect allocation of demand to capacity is unlikely due to airline and passenger preferences for particular airports so the above timescales understate the lack of demand at the airports of first preference.

Can growth be controlled using taxation?

One potential solution is to increase taxation on aviation (a lightly taxed industry according to many) such that demand is contained within the existing infrastructure. But the question has to be what type of demand to tax? Short-haul demand and transfer traffic are the two obvious candidates as these sectors can use alternate airports or modes.

Short-haul routes

Apart from Eurostar and a handful of ferry routes there is little alternative to flying to most international destinations. Even Amsterdam (230 miles from London) is a trip made mainly by air as travel by rail takes five hours. In reality, short-haul air travel only exists to feed the long-haul network or due to Britain’s status as an island. Short-haul domestic routes have reduced considerably, partly because of investment in the rail system but 40% of the domestic traffic into London’s two main airports are actually transferring on to other longer-haul flights and make up a comparatively small proportion of slots at both the main airports so there is not much to be gained.

Transfer traffic

34% or 23 million passengers flying through Heathrow are transfer passengers of whom an estimated 28% (18 million) are international to international transfers.

Surely an obvious target for diminishing by taxation? An airport the size of Heathrow will always have connecting passengers, their presence enables airlines to fly routes that would not otherwise be sustainable. The airlines will argue that reducing connecting traffic over Heathrow will merely lead to fewer direct routes and smaller aircraft. On average 47% of British Airways passengers are connecting, as are 44% of Air Canada, 33% of South African Airways and even 19% of Lufthansa and 12% of Air France passengers. On particular routes more than half the passengers can be connecting onto other flights, the economics of a daily service might not be viable without connecting passengers on routes such as Seattle, Phoenix, Chennai and Bangalore to name a few. A tax on transfers could lead to a significant reduction in London’s long-haul air network and potentially damage London’s role as a business city. For UK regions, the impact of losing access to the global aviation network is also a concern. However the counter to that particular argument is the existence of air services from the regions to other hubs (Amsterdam, Paris, Frankfurt and Dubai all have extensive connections to UK regional airports).

Increased Use of Surface Modes

High-speed rail has done a good job of and replacing short-haul air travel in markets such as Germany and France but so far not in the UK where the planned route of the proposed North-South High Speed 2 rail line does not serve Heathrow (a proposed station at Acton is 15 minutes by train from Heathrow).

Where rail does form an effective replacement to air travel, rail will take significant traffic from competing air services. The success of the high-speed Eurostar services serving Paris and Brussels from London and the success of improved conventional rail services between London and Manchester both illustrates this. However, neither rail services have eliminated air services between London and these three cities. There are three main reasons why short distance air services have not been eliminated:

- The remaining passengers are often transfer passengers using London as a transfer point to transfer to a more distant ultimate destination;

- The train services only serve London’s central area and are not as convenient as the airports for many passengers; and

- Airlines can compete on price.

The table below illustrates how little Heathrow traffic could be diverted to a high-speed network. Even assuming destinations as far distant as Frankfurt and Dusseldorf could be diverted (needing a direct rail link to Heathrow taking no more than three hours) only some 10 million passengers or 15% of traffic could be diverted to rail.

| Core | Rail replaceable | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | 1.37 | 4.70 | 6.07 |

| EU | 17.36 | 5.88 | 23.23 |

| Other Europe | 5.38 | 0.00 | 5.38 |

| Long-Haul | 36.07 | 0.00 | 36.07 |

| Total | 60.18 | 10.58 | 70.76 |

Diverting Demand to Regional Airports

A common cry of regional politicians and UK regional airports is that the UK regions have the capacity to soak up much of the excess demand from the London airports. Their case is supported to a certain extent by CAA ultimate origin and destination statistics that show many millions of passengers travelling to and from London to catch flights from London’s airports. Only 74 million (72%) passengers out of 103 million origin destination passengers at London’s four largest airports had their ultimate O&D in the South East. The other 28% (or 29 million) had ultimate O&Ds in the Regions. Simplistically, these 29 million passengers would have possibly preferred to use their local airports.

The reason why this is not possible is down to the airlines, they have not found a profitable way to serve those 29 million passengers. There are very few barriers to airlines to fly from say Manchester to Los Angeles and Manchester airport would be delighted to offer incentives to do so. The harsh reality is British Airways did fly the route briefly but withdrew despite high load factors presumably because they could not make viable financial returns. However, airlines such as Emirates have found a way to serve regional airports profitably so in the future it is likely that more routes will become viable in the longer term, especially with the advent of lower cost long-haul capacity such as the 787. Like high-speed rail, attracting (not diverting) air services to the regions helps capacity in the South East but is very unlikely to provide more than a marginal contribution to meeting the London capacity demand. Regional air services should be encouraged where financially feasible.

What is the Business Case?

An additional runway at Heathrow is what the aviation industry wants. Most airlines wanting access to Heathrow are willing to pay for it and the economic benefits are stated to be in the billions.

A three runway Heathrow would probably have capacity in the order of 120 million passengers a year. Using a similar approach to the previous illustrative forecasts, 120 million capacity could last up to 2050 depending on economic growth and the selective use of the APD to control demand.

Why is expansion at Heathrow so unpopular?

However, the whole idea of expanding Heathrow is deeply unpopular in the area around Heathrow on noise, congestion and pollution grounds even though the proposal is that the third runway be restricted to narrow body flights only. Partly environmental problems can be addressed by compensation, noise insulation and a switch to rail rather than road access. However the issue remains; Heathrow and its flight paths are situated in densely populated and a wealthy areas. Many of the local inhabitants place a very high price on living where they do, probably a much higher price than any compensation scheme on offer, this does suggest that higher levels of compensation may be part of the answer. As was the case with the Olympics, removing car parks alleviated much of the traffic congestion issues and drove Olympics spectators onto the public transport network. Harder to achieve with passengers carrying baggage but compared to other airports such as Amsterdam and Frankfurt, Heathrow access to anywhere but Central and West London remains poor hence public transport only achieves 41% market share, there is much more that could be done to improve rail access to London, starting with changes to the proposed HS2 route and access to the Great Western and Southwest rail lines.

Is Gatwick an alternative solution?

Gatwick’s new owners are examining the idea of a second parallel runway. No actual physical construction work can start prior to 2019 (due to an agreement with local authorities), but given the planning issues any such scheme will raise, that date should not be a hindrance.

The key question is will demand be sufficient to finance a second runway? A third runway at Heathrow would likely lead to a mass exodus of some Gatwick flights to Heathrow in the short term (up to 5 million passengers depending on what scenario one uses) but in the long-term Gatwick is the favoured point of departure for about 20% of the London market given its excellent rail access and wealthy hinterland. It is likely that much of the increased demand unleashed by a second runway would in fact come from Stansted and Luton due to the higher yields historically earned at Gatwick.

In the long-term a second runway at Gatwick is probably justifiable economically but investors will require considerably certainty before financing it. That means that everyone will need to have confidence in the outcome at Heathrow before committing to financing a new runway at Gatwick.

If no third runway was built at Heathrow and a second runway built at Gatwick it is likely that network carriers would incrementally build up services connecting Gatwick to other hubs. Apart from a minor role as a hub already (13% of passengers are connecting) Gatwick’s main role is likely to be as a feed ‘spoke’ to other hubs for network carriers such as Emirates and Korean. But the experience post the liberalisation of the USA bilateral where virtually all the USA bound flights (except to Florida) transferred to Heathrow illustrates the problems Gatwick has attracting airlines if not passengers.

Expansion of Stansted or Luton Airports

The only votes in favour of these proposals are probably from those opposed to expansion at Heathrow and Gatwick. The main obstacle to these proposals is a lack of demand from airlines, who like it or not control the market. In particular, the main problem for most airlines are the existing incumbents: easyJet and Ryanair. These two low-cost Goliaths would make it very difficult for any new short-haul airline to enter these two markets.

At present, it is very hard to see how expansion at either Stansted or Luton could be financed given the opposition of the existing airlines using these airports to increased fees. The likes of Ryanair will point to the decline in traffic at Stansted in recent years as evidence that the existing fees are too high never mind the fees for a new runway. In reality, the existing airlines would probably prefer to keep both airports as they are, content to collect increasing fare revenues as capacity gets tighter in the London market rather than pay more to let competition in.

A New London Airport in the Thames Estuary

One proposal is to build a new hub airport for London with at least four runways on a site in or adjacent to the Thames Estuary, possibly in association with a new Thames barrier with high-speed rail links to Central London. What are the issues:

- No demand (which airlines would serve the airport?);

- Heathrow and Gatwick compensation;

- High cost (who is going to pay?); and

- Poor access to rest of UK (how would passengers coming from the West of London or the regions access the airport?)

Dealing with these issues, how would one go about financing an Estuary airport?

Demand

The first issue to address is that of demand. To be a successful hub requires a successful hub airline. Schemes to launch a new hub airport occur ever so often but as the five examples below suggest, success is not guaranteed, especially if the existing hub airport remains open.

Enforced transfer of air services to a new airport

To succeed, the Estuary Airport would require the transfer of many air services to the new airport. This approach has been used in the USA, where Dallas Fort Worth was made a success by forcing all but Intra-State and bordering States air services to transfer to the new a airport. A similar approach was adopted in the Washington and New York areas. In Europe, the rules have to comply with European competition rules covering competition between airlines. The proposal to make Linate an airport only serving flights to Rome failed. Instead flights had to be allowed to all the major hub airports in Europe. This competition crippled Malpensa’s network and contributed to the near collapse of Alitalia.

Since almost all agree that the stated point of a new estuary airport is to provide London with a new hub, it has to gain a hub airline, the most obvious candidate being British Airways. What would make BA transfer to the new airport, located as it is on the wrong side of London? There are a number of prerequisites that ideally need to be met:

- Adequate airport infrastructure, runways, terminal and baggage systems capable of handling waves of probably at least 100 flights per hour, a four parallel runway system is therefore the minimum requirement;

- Adequate access infrastructure, not just to central London but beyond to the West of London and beyond to the West and North, HS2 and the proposed revamped Great Western Network will need to be linked directly to the airport as well as HS1 to Paris and Brussels;

- Adequate housing for the 75,000-100,000 employees within reach of the airport;

- Protection from competition from other London airports. The other airports will probably need to be closed or limited in what air services they can operate. Who compensates who and for what? Private companies such as the owners of Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted etc will require compensation for loss of business if their access to air services is suddenly restricted.

The shaded box illustrates just how complex it will be to transfer traffic to the new airport and the requirement not just to manage demand at Heathrow but also at the other London airports. The key conclusion is that overall traffic will fall as routes become unprofitable either due to higher fees or lower levels of transfer traffic. Main losers are passengers (higher fares and access costs) and airlines, especially British Airways and Virgin Atlantic due to loss of transfer traffic.

Conclusions

In the absence of a new runway at Heathrow or a new airport, London’s role as a global hub will be diminished and possibly with it, the role of London as global city.

As the discussion above illustrates, there are numerous issues to be resolved before there can be a coherent and workable strategy for London’s airports. The matter is pressing. Will the politicians have the courage to come out with a workable solution? A strategy that meets the demands for air travel but also recognises and tackles the environmental costs that any such an expansion might cause? What has been recognised by the current generation of politicians is the need for a policy supported by all sides in Westminster and no sudden changes down the road for political expediency. With the Davies Commission due to report at the end of 2013, the need for some convincing answers is pressing.