Spain's medium-sized airlines adjust to troubled times

November 2009

A weak domestic economy and fierce fare wars are prompting major restructuring among Spain’s medium–sized airlines. But are they doing enough to fend off the growing threat from foreign LCCs?

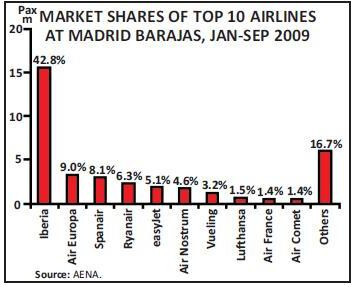

While Iberia continues to be distracted by its on/off merger with British Airways, Ryanair and the other foreign LCCs continue to carve out larger portions of the Spanish domestic and international markets. Ryanair, of course, is at the forefront and is now second only to Iberia in terms of passengers carried, according to statistics from AENA, the Spanish airport authority (see chart, below). Most worryingly for everyone else, Ryanair wants to become the largest airline in Spain within the next two or three years, according to CEO Michael O’Leary.

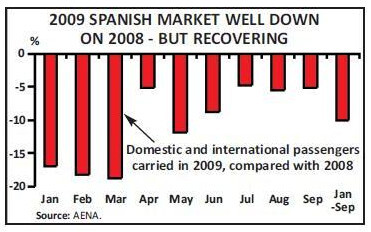

If this wasn’t bad enough for Spanish airlines, the domestic and international passenger boom of the 2000s has come crashing to a halt this year, thanks largely to the recession but also to other factors such as the popularity of the expanding high–speed train network in Spain. Alex Cruz, the former CEO of Clickair and now CEO of Vueling, says that “the drop in demand in passengers flown in Spain has been staggering” – passengers carried in the January–September 2009 period were 10% down on the same period in 2008, although the year–on–year gap is closing as 2009 progresses — see chart.

Spanair targets Barcelona

Unsurprisingly, these market developments have led to major changes at Spain’s medium–sized airlines. Spanair was established by SAS and tour operator Viajes Marsans back in 1988 as a charter operator, before expanding into long–haul services in 1991 and developing an extensive scheduled network in 1994. The long–haul services were stopped once SAS took full control of the airline, and Spanair currently operates to 18 scheduled destinations in Spain and seven in the rest of Europe, plus Algiers, Casablanca and Banjul in North Africa. 13% of its flights are charters and the rest scheduled, where it specifically targets business travellers.

SAS restructured Spanair in 2008, including a 1,000–strong reduction in the workforce, downsizing the fleet by 15 aircraft and cutting five operational bases, leaving services concentrated on Madrid and Barcelona. SAS claimed that this would reduce costs by €90m in 2009, leading to break–even for the airline in 2010.

But even with this restructuring, Spanair never fitted sensibly into the Scandinavian airline’s long–term strategy, and as far back as 2007 SAS announced it would sell the Spanish carrier as it was no longer considered a core business. However, this was not completed until March this year when 80.1% of the airline was sold to a Barcelonabased private/public consortium called Empresarials Aeronautiques (IEASA), which includes Catalana d'Inciatives — a VC fund — as well as Consorci de Turisme de Barcelona, Volcat 2009 (part of FemCat foundation, which promotes the Catalan economy and culture) and trade fair company Fira de Barcelona. One of the shareholders in Catalana was the Lara family, which also had a shareholding in Vueling through Inversiones Hemisferio, and so subsequently sold its 5% stake in the VC fund to the Barcelona city council and the Instituto Catalan de Finanzas in order to avoid a conflict of interest.

IEASA initially paid a nominal €1 for its stake in Spanair, but at the same time agreed to invest a further €70m into the airline, as well as raising another €30m from non–Catalan investors, who would subsequently join the consortium. The target date for completion of this €100m fundraising is end of the year, and if successful it’s likely that SAS may exit completely from its remaining 19.9% of Spanair, which it retained only through having to convert €20m of loans to Spanair into equity as part of the deal to attract new investors.

Catalana’s choice as its new CEO of Spanair was Mike Szucs, previously CEO at Mexican LCC VivaAeroBus and director of operations at easyJet, who took up the position in June. Catalana has been undergoing a strategic review of the airline since it acquired control and it’s an open secret in Catalonia that the airline will return to long–haul flights by 2012 at the latest. Spanair agreed code–sharing with Air Canada in May (the latter operates a Toronto–Madrid service) , but the tentative plan is to operate routes to South America from Barcelona using around five aircraft initially – most likely to be A330s in the shorter–term, but potentially A350s from 2013 onwards as it builds up a long–haul fleet of more than 10 aircraft.

Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires will be the first routes to be served, and the airline is currently arranging the relevant traffic rights. At the same time as building up long–haul services, Spanair will wind down its remaining charter business, which currently stands at around 10% of all its flights. Margins are falling fast in the Spanish charter market, and it’s a business that has little interest for the Catalana consortium.

The international expansion goes hand in hand with a core goal of turning Barcelona airport into an international hub. While Spanair is not publicly stating it will reduce its Madrid operations, sources suggest this is the intention in the long term, as the key target of Catalana is to develop Barcelona airport into not just a rival to Madrid, but into the premier airport for the whole of the Iberian peninsula, and with a catchment area that extends into southern parts of France.

As part of this strategy the airline has moved its headquarters from Palma de Mallorca, to Barcelona’s new Terminal 1, into which it switched its Barcelona operations in June. Not all the 380 staff in Palma chose to relocate to Barcelona; the ones that didn’t received redundancy packages of 20 days pay plus €750 per year of employment, although this was agreed only after the Palma staff held a series of one–day strikes through August.

Long–haul expansion is likely to be accompanied by a trimming of domestic services (Spanair started domestic code–sharing with Air Europa in March this year),although routes into the rest of Europe are likely to be unaltered in the short–term.

Spanair’s fleet today stands at 47 aircraft, although in September the airline announced it would cut capacity by 10 aircraft by 2010. The four 717s will be kept, it is believed, but the current 19 MD–80s (two MD–82s, six MD–83s and 11 MD–87s) will be gradually trimmed back. Many of the MD–80s are on leases (and most of those from SAS), of which 13 will expire between now and the end of 2010. They will be replaced partly by A20 family aircraft, with either a new order placed in 2010 or through leases, depending on how the airline’s finances develop over the next year or so.

Whereas Spanair made a net loss of €218m in 2008, the airline is expecting to break–even this year before posting a net profit in 2011. An EBITDA loss of around €5m is expected in 2009, prior to an EBITDA profit of €84m in 2010. But the figures depend on a lot of factors, including the successful development of international routes out of Barcelona and continued cost cutting. Ferran Soriano, the president of the airline, told Catalan media that a reduction in the overall workforce could not be ruled out in order to return the carrier to profitability in 2010; the airline currently has a workforce of approximately 3,300.

On the other hand Spanair may also take its handling operation in–house as there have been operational issues with handlers at Spanish airports, and particularly with slow turnaround times. In September Spanair became involved in a public argument with ground handler Marsans Newco, and refused to pay a 17.5% increase in its fees that Marsans imposed from January of this year. The two companies have a contract that expires in 2012 and Marsans claims it is owed at least €10m in fees. Unsurprisingly, the dispute may well end up in court.

Vueling: still in ownership limbo?

While Spanair’s routes were previously co–ordinated with the hubs of SAS and Lufthansa around Europe, in competition against Iberia, that is no longer the case, although Spanair remains a member of the Star alliance (which it joined in April 2003). Ferran Soriano says that Spanair now sees its main competition as being the other LCCs. The long awaited merger between LCCs Vueling Airlines and Clickair was completed in July this year, and the Clickair name was immediately dumped in favour of Vueling’s perceived stronger brand. Alex Cruz, the CEO of Clickair since its launch in May 2006, became CEO of the merged company, with Josep Pique, chairman of the pre–merged Vueling, continuing in that position in the new company.

The enlarged carrier now operates to 45 destinations in Europe and North Africa with a fleet of 35 A320s, of which 17 were previously at Vueling and 18 at Clickair. The two airlines overlapped on 17 routes, and that saved capacity has been placed elsewhere within the network.

Vueling has been working on a three–year strategic plan, which is due to be unveiled before the end of the year, but at present the new airline has a 70:30 split between leisure and business passengers. It follows a typical LCC business model, charging for extras such as baggage, priority boarding and extra wide seats, although one of its aims is to better develop stronger ancillary revenue streams.

Iberia, which previously owned 20% of Clickair, had acquisition rights for the other 80% of that airline, which brought its stake in the “new” to 45.85%. The other shareholders were Inversiones Hemisferio (owned by the Lara family) with 14.3%, Nefinsa (the owners of Air Nostrum) with 4.2% and the remainder on free float. In late October Inversiones sold its stake for €43m to a variety of institutional investors.

However, Iberia’s current shareholding — just short of 50% — appears untenable in the long–term. Although Vueling “competes” against the flag carrier on a handful of routes and Iberia says Vueling is free to make its own commercial decisions, that’s highly unlikely in practice. Indeed in September Vueling tried to counter growing criticism of its relationship with Iberia by launching a grand–sounding “independence commission” to ensure it is free from influence from Iberia and to make decisions on any conflicts of interest between Iberia and Vueling.

That commission has met with scepticism from many observers in Catalonia, citing the fact that Iberia’s’ 46% shareholding in Vueling gives it enormous influence, whether explicitly or implicitly, and that it would be illogical for Vueling’s management to put any strategy in place that would be detrimental to Iberia. In August, for example, Vueling joined Iberia Plus — Iberia’s FFP.

Under Spanish stock exchange rules, once Iberia’s shareholding in Vueling passed 30% it should have had to launch a takeover bid for Vueling, but it has been granted an exemption to this by the financial regulator. However, should BA acquire or merge with Iberia this exemption would lapse, and Iberia would either have to seek another exemption (which would be unlikely to be granted), launch a bid for all of Vueling or reduce its shareholding significantly.

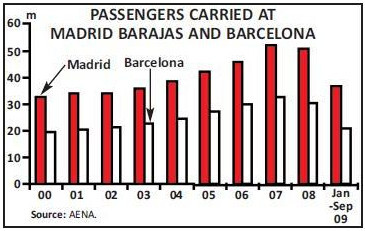

As BA’s track record with LCC subsidiaries is not great (i.e. Go, which BA sold pretty quickly), if BA and Iberia do merge it would not be a surprise if Iberia reduced its shareholding in Vueling. But there is also a (stronger?) argument for acquiring all of Vueling. In September Josep Pique, the chairman of Vueling, said that a merger between Iberia and BA would benefit Vueling, as Vueling would be able to “take advantage” of Iberia’s improved competitive and strategic position post–merger. More importantly perhaps, from an Iberia/BA point of view a 100%-owned Vueling would give it a real means of fighting the LCC challenge as well as preserving valuable “blocking” position at Barcelona airport (see chart).

Iberia withdrew a bid for Spanair in May 2008, due to “concerns” over the state of the Spanish market, and Iberia’s latest strategy (as of July) is to reposition itself as a “luxury” full–service airline in competition against other flag carriers. With Vueling competing head on with Ryanair, easyJet, Air Berlin and others, one analyst describes Vueling as becoming the sacrificial lamb in Iberia’s overall strategy. And yet another “paradigm shift” announced by Iberia in late October (called Plan 2012) now also puts the emphasis on building up (yet again) a long–haul network out of Madrid, with a new airline based in Madrid being set up to feed traffic via a short–haul network. This would not exactly dovetail with Vueling’s emphasis on Barcelona, although — frankly — Iberia’s strategy cannot be considered to be settled until the BA merger is sorted out one way or another.

As for Barcelona, in September Vueling moved its operations there to the new Terminal 1, at which Iberia and its regional feeder, Air Nostrum, as well as all other oneworld partners are located. Terminal 1 now handles 70% of all traffic at the airport (including Spanair, Star and SkyTeam airlines) and it will enable the airport to redevelop Terminal 2 (the existing A, B and C terminals) in 2010. Terminal 1 can handle up to 30m passengers a year, which doubles the overall capacity at the airport.

Altogether Vueling has six operational bases (Barcelona plus Madrid, Seville, Bilbao, Valencia and Malaga), and will carry around 11m passengers in 2009 on 90 routes. However, it is Barcelona where Spain’s key aviation battle will be fought over the next few years, given the ambitions of Spanair and others. But competition, at least domestically, also comes from AVE, the Spanish high–speed train. For example, on the key Madrid–Barcelona route the enlarged Vueling has a 25% market share, although it faces fierce competition from AVE and — at least until now — from Iberia. Vueling is increasing flights on the route to 12 a day from the winter 2009/2010 season, and what Iberia does with its capacity on the route will be a key test of how much Vueling and Iberia will compete in the future.

Unsurprisingly, the new Vueling now dominates traffic at Barcelona airport (see chart, right). The European Commission was concerned about the impact of the merger on routes between Spain and Italy and France, and allowed the deal on condition that the two airlines gave up slots at Barcelona and other airports. However, the slots given up are believed to be sufficient for just over 100 weekly flights across all these sectors, which Vueling considers acceptable.

Both Clickair and Vueling made operating losses in 2008, although Vueling just crept into a net profit of €8.5m for the first time since its launch in 2004 (though this was thanks largely to an accumulated €47m tax credit). In the first nine months of 2009 Vueling reported a €71.9m operating profit, compared with a €18.7m loss in January- September 2008, based on a 25.1% rise in revenue to €441m. In the nine month period EBITDAR rose by four times its 2008 level, to €122.8m in 2009.

The priority for the new airline is to break into profit, and it is targeting cost savings of up to €25m this year and in each of the next two years, plus an annual increase in revenue through synergies of €45m – i.e. the merger should boost the bottom line by up to €70m this year.

On merger the combined workforce of the two airlines was 1,600, but this is being trimmed to 1,300, with around 50 positions going through the merger of the airlines' headquarters and others going through the outsourcing of ground handling.

The fleets at the pre–merger airline had already come down significantly recently – from 24 at Vueling and 26 at Clickair in 2008, and Vueling had restructured significantly through 2008, cutting a number of routes as its fleet was reduced by one–third.

Air Comet’s uncertain future

Overall, the cost cuts from the merged airlines have now largely been implemented, and although there will be significant merger and restructuring costs, the enlarged airline believes that will it post a pre–tax profit for 2009, based on revenue of around €800m. With just 13 aircraft (10 of which are owned outright), Air Comet is much smaller than its main rivals in Spain, although it had once wanted to become the second largest airline in Spain.

However, the prospects for Air Comet continuing as an standalone airline brand are close to zero. The Madrid–based airline is part of Grupo Marsans transport and tourism giant (see Aviation Strategy, December 2007), but Marsan’s aviation ambitions are now in tatters, and as a result the fate of Air Comet is uncertain.

Marsans had wanted to build up a huge air bridge between Europe and South America, connecting hubs at Madrid, Barcelona and Buenos Aires, but one of its airlines, Aerolineas Argentinas, was re–nationalised in July 2008, while another of its airlines, Air Comet Chile (not related to Spain’s Air Comet) went bankrupt last December. This leaves Marsans holding onto a massive aircraft order backlog, based largely on a November 2007 order for 61 Airbuses at a list price of €5bn, comprising five A330–200s, 10 A350, four A380s, 12 A319s, 25 A320s and five A321s.

While Marsans is still trying to persuade the Argentine government to take 30 Airbus aircraft earmarked for Aerolineas (and has also taken the government to the World Bank over the re–nationalisation), even if this action is successful it will still have nowhere else to place the remainder of its huge backlog other than its sole Spanish airline, Air Comet. As part of Marsan’s grand strategy that airline was supposed to turn itself into a long–haul airline competing against Iberia, but with the loss of the South American side of this plan Air Comet is an airline with no strategic purpose and no prospects of utilising the massive capacity that Marsans has on order.

A330s, for example, are arriving at the rate of one new aircraft a month through 2009, and for the moment Air Comet is using them to increase frequencies on its existing routes between Madrid and seven destinations in Latin America (having suspended routes to Santiago de Chile and San José, Costa Rica in September).

Clearly though, new destinations would have to be found for all the new long–haul capacity supposedly coming on–stream, and then there are large numbers of A320 family aircraft to place as well.

Once upon a time another ambition of Marsans was to buy Spanair, and it’s likely that the ambitious orders by the group were earmarked partly for a potential acquisition. The reality now is that the aircraft have to be shoe–horned into Air Comet, disposed of in the open market, or – much more likely – cancelled. Marsans also wanted to launch a hub in Barcelona, connecting transatlantic routes with European routes, but again that idea looks dead given the Marsans’ group situation and the grip that Vueling has at Barcelona.

Marsans has already been in negotiations with both Orizonia and Globalia, two rival travel industry conglomerates, about a potential merger with Marsan’s remaining aviation asset, but both these companies have their own airlines (Iberworld and Air Europe respectively), so whether they would want Air Comet as part of a merger is open to doubt.

Marsans is now explicitly stating that it wants to sell Air Comet independently of other Marsans businesses, though it’s difficult to see where prospective buyers may come from. Marsans held talks with Spanair in September, but the rival airline decide to back away from buying it, saying that it was instead prioritising cost–cutting at its own operations.

Although the actual figures are buried deep within Marsans’ accounts, Air Comet is reported to have considerable debt and problems with bank funding, and in August further unconfirmed reports out of Spain suggested that the owners of Marsans, Gonzalo Pascual and Gerardo Diaz Ferran, had to inject personal funds into the airline. Indeed pilots at Air Comet came close to strike action in September after a dispute on conditions and unpaid salaries, although this was resolved at the last minute when management promised to pay salaries owed for July and August.

In October Air Comet’s chief executive, Jose Maria Llodra, resigned, to be replaced by Eduardo Aranda, but his scope for action is limited given that the airline is up for sale.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| Spanair | |||

| A320 | 19 | ||

| A321 | 5 | ||

| 717 | 4 | ||

| MD-80 | 19 | ||

| Total | 47 | 0 | 0 |

| Vueling Airlines | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A320 | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Air Comet | |||

| A320 | 2 | ||

| A330 | 4 | ||

| A340 | 2 | ||

| Total | 8 | 0 | 0 |

2008 passengers (000s)

by flight country of origin/destination

| Madrid Barajas | Barcelona | Barca as % of Mad | |

| Domestic | 20,858 | 12,581 | 60.3% |

| Europe | 17,370 | 13,454 | 77.5% |

| North America | 1,730 | 639 | 36.9% |

| Latin America | 6,334 | 1,019 | 16.1% |

| Other long-haul | 4,554 | 2,579 | 56.6% |

| Total | 50,846 | 30,272 | 59.5% |