Northwest: Out of Chapter 11 and into profitability

November 2007

Northwest is currently one of the most profitable US airlines, thanks to its hugely successful Chapter 11 restructuring.

Having attained a competitive cost structure, repaired its balance sheet and kept in place a $6bn re–fleeting programme, the Minneapolis–based carrier is well positioned to make the most of its unique assets, which include a large Pacific network and a hub at Tokyo Narita. But can an airline with chronic labour problems and poor morale really succeed in the long term?

Northwest accomplished essentially everything it set out to do in Chapter 11: cutting annual operating costs by $2.4bn, slashing debt and lease obligations by $4.2bn, solving the pension problem and right–sizing the fleet. The airline shrunk by 10% in terms of ASMs and optimised its network by eliminating less profitable routes, strengthening key hubs and adding new international service.

As a result, Northwest has the lowest unit costs among the US legacies and is achieving industry–leading profit margins. It has just reported a healthy $405m pretax profit before special items for the third quarter. The 12% pretax margin was the second- highest in the industry (after Alaska’s 14%).

Significantly, Northwest was able to keep in place its aggressive long–haul fleet renewal programme: all of its A330 and 787 orders were reaffirmed in bankruptcy.

Given that the 787 is now sold out until at least 2012, Northwest, the type’s North American launch customer, is fortunate to hold delivery positions for 18 firm orders and 50 options from early 2009. The A330 and 787 fleets will give Northwest an important competitive advantage.

But Northwest’s turnaround and promising prospects are not reflected in its share price, which has fallen by 32% since the new shares began trading following the Chapter 11 exit at the end of May — among the sharpest declines in the industry.

The stock has declined, first, because Northwest emerged from Chapter 11 at a difficult time. First there were fears of weakening domestic demand, oil prices then surged and now there is talk of a possible economic slowdown in 2008 (of which airlines have seen no sign so far).

Second, in June and July Northwest suffered a rise in flight delays and cancellations due to absenteeism among pilots. This caused negative publicity just as the airline needed to rebuild its image after bankruptcy. The problems were solved by August, but Northwest had to trim its domestic flight schedule, boost pilot hiring and renegotiate contract issues and work rules with its pilots.

Third, like Delta’s stock, Northwest’s shares have been volatile due to selling by creditors who received equity for their unsecured claims. That process is still under way, though at least Northwest does not have the uncertainty of the PBGC (the government) holding a sizeable equity stake (as is the case with Delta).

The magic combination of low share price and promising prospects has obviously presented a buying opportunity, prompting investors to take a look. At least ten analysts have reinstated coverage of Northwest in recent months; of those, seven currently recommend the stock as a "strong buy" or "buy".

In addition to the attractive valuation, analysts have mentioned Northwest’s lower cost structure, good RASM momentum, sector–leading profit margins, de–leveraged balance sheet, profitable re–fleeting, long term labour agreements and experienced management. The airline’s special attributes include a strong franchise, with dominant positions at Minneapolis and Detroit hubs, a large Pacific network, 376 weekly slots at Tokyo–Narita, fifth freedom rights from Japan to Asia, great alliances, a sizeable cargo business and less than typical exposure to LCCs.

But Northwest has an Achilles heel: an unhappy workforce — a potentially serious flaw in a service oriented industry like airlines. The key question regarding Northwest’s otherwise promising future is: To what extent will labour ruin it?

While financing the orderbook is not believed to be a problem, major fleet renewal in a downturn poses risk. Even in the best scenario, Northwest will have little free cashflow in the next few years. What impact will the fleet renewal have on its balance sheet?

A major point of interest is what Northwest could eventually do in Asia. Will it, as it has recently hinted, use its Tokyo slots and traffic rights to build service to secondary cities in China?

The Chapter 11 reorganisation

Northwest filed for Chapter 11 on September 14, 2005, the same day as Delta. Lack of liquidity was the trigger: the airline realised that it would end the year with only about $950m in cash. Its labour costs were out of control. Despite extensive cost cutting, Northwest had lost $4bn since 2000 and had $12bn in debt.

It was a swift reorganisation, lasting only 20 months — a month longer than Delta’s. Northwest converted its $1.2bn DIP credit facility into a Chapter 11 exit financing, which is secured on its Pacific route rights, and also raised $750m in a new equity rights offering. The new stock was listed on the NYSE under the symbol "NWA".

Based on the total of 277m new common shares (when all the distributions are completed) and the initial trading price of just over $25 a share, Northwest was valued at about $7bn when it emerged from Chapter 11. Most of the shares went to unsecured creditors, who recouped 66- 83% of their claims in stock — an extremely generous payout by recent airline bankruptcy standards. Unsecured creditors were also invited to subscribe to the rights offering; only about 10% did so. Of course, secured creditors were paid in full. As is typical in airline Chapter 11 cases, former shareholders were left with nothing as the old stock was cancelled.

Another group that was treated well was Northwest’s management. The top 400 executives and managers will receive 4.9% of the new equity over four years, worth $340m at the initial valuation. CEO Doug Steenland’s share is around $30m, with four SVPs receiving more than $10m each. The awards are in the form of restricted stock and stock options and will only have value if the business plan targets are achieved and the stock price appreciates. The stated aim was to reverse a high attrition rate and retain high–quality management.

Northwest granted its workers $1.25bn in unsecured claims in exchange for concessions. This would have given labour a 14% ownership stake based on the initial valuation, but the unions chose to sell their stakes and distribute the cash proceeds, totalling $960m, to members. In addition, Northwest put in place a profit–sharing plan that is projected to pay out $500m over five years.

Thanks to the provisions of the Pension Protection Act of August 2006, Northwest (like Delta) avoided the trauma of pension plan terminations. Keeping the defined benefit pension plans avoided the loss of some $2.1bn of retirement benefits at Northwest. However, the old plans were frozen in respect of future benefit accruals and new cheaper defined contribution plans were put in place for most labour groups.

Despite those positives, overall it was a rough deal for the workers. The unsecured claim and profit sharing payouts will nowhere near make up for the workers' sacrifices. Northwest’s employees had granted $1.4bn worth of annual concessions. Pilots had taken 40% pay cuts. The airline had used court permission to void a contract with its flight attendants and impose new conditions. Flight attendant pay at Northwest now tops at just $35,400 a year, down from $44,200 before Chapter 11.

Consequently, Northwest’s Chapter 11 process was characterised by labour strife, particularly in the final months when the workers knew of the healthy 2006 profit and the executive stock award plans. In the final weeks there was even a strike threat hanging over the airline. The flight attendants ratified their concessionary contract with the narrowest of margins (50.9%) and only two days before the Chapter 11 exit.

It will also be remembered as the airline Chapter 11 case where holders of the old equity fought back. In late 2006 several hedge funds had built up large positions in Northwest’s old equity on speculation that US Airways' hostile bid for Delta would lead to a merger wave in the industry. When that fizzled out and airline stocks plummeted, the hedge funds fought unsuccessfully to recover their investments, among other things, by opposing the Chapter 11 plan and pressing Northwest to consider a merger.

The hedge funds succeeded in getting an examiner appointed to look into whether Northwest had made reasonable efforts to explore value–boosting merger possibilities. The conclusion was that Northwest had acted appropriately, except that it had not assigned proper value to its "golden share" in Continental, which gives it veto powers over any Continental merger. The examiner noted that Northwest was under no obligation to market itself to another airline. The hedge funds eventually settled with Northwest, agreeing to drop their objections to the Chapter 11 plan in return for Northwest paying up to $5m of their legal bills.

As of late October, Northwest had about $1.1bn in remaining disputed unsecured claims to be resolved, to bring the total allowed unsecured claims to $8–8.4bn.

Northwest’s new 12–member board of directors looks exceptionally strong. Roy Bostock, a principal of private investment firm Sealedge Investments and a Northwest board member since 2005, took over as chairman from 67–year–old Gary Wilson (who led the leveraged buyout of Northwest in 1989). The board gained five new members, including former US transportation secretary Rodney Slater, former Northwest CFO Mickey Foret and former AMR CFO Mike Durham.

Profits and CASM: from laggard to leader

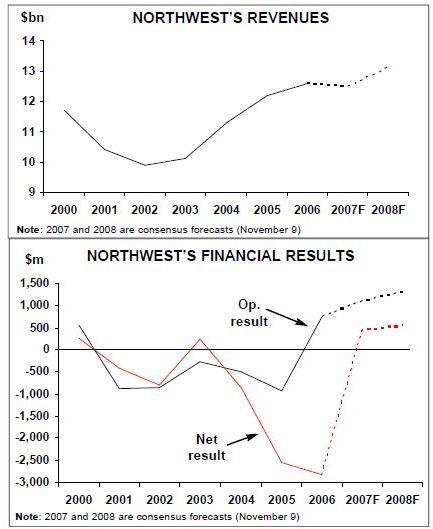

The highly respected top management that oversaw the restructuring stayed on. The team is led by CEO Doug Steenland, 55, a lawyer who joined Northwest in 1991, became president and a board member in 2001 and was named CEO in 2004. Like its legacy peers, Northwest returned to profitability in 2006 after five years of heavy losses. Last year the airline earned a modest $301m pretax profit before reorganisation items, accounting for 2.3% of revenues and broadly in line with industry results. But this year Northwest’s profit performance has been truly impressive, far exceeding that of its peers.

Northwest earned a $778m pretax profit in the first nine months of 2007; the 8.2% pretax margin was the best among the network carriers. The September quarter’s 12% pretax margin (typically Northwest’s strongest quarter) was well above the 4–9% margins achieved by the other legacy carriers and higher than Southwest’s 10%.

The third–quarter $405m pretax profit was Northwest’s highest quarterly profit in ten years and the third highest in its history. Operating margin was 13.6% — an amazing achievement in the current fuel cost environment.

The results are obviously testament to the success of the Chapter 11 restructuring. However, S&P’s Philip Baggaley made the point recently that Northwest did not have as many problems to fix as Delta. Its non labour costs were in relatively good shape and its revenue generation was not below par.

Since filing for bankruptcy, Northwest has reduced its annual costs by $2.2bn and is on track to achieve a further $200m in savings. The $2.4bn total includes $1.4bn in labour cost savings and $400m in fleet ownership cost savings. The remainder came from savings in interest expenses ($150m), pension costs ($100m) and non labour costs ($350m).

The $2.2bn savings to be achieved by year–end 2007 represent about a 15% reduction in ex–fuel unit costs over two years, from 8.48 cents per ASM in 2005 to around 7.22 cents in 2007 (the latter is a late–October forecast by Merrill Lynch).

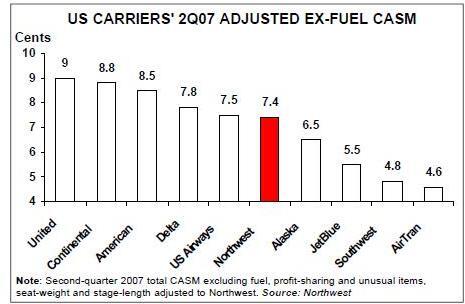

The result is the most competitive cost structure among the network carriers. Northwest calculated that its second–quarter ex–fuel seat–weight/stage–length adjusted CASM of 7.4 cents was right at the bottom of the legacy carrier range, below United’s 9, Continental’s 8.8, American’s 8.5 and Delta’s 7.8 cents. It was even below US Airways' 7.5–cent CASM — a carrier that is essentially a "hybrid" legacy/LCC. The differential between Northwest and the top three LCCs was 2–3 cents.

The reason Northwest’s ex–fuel CASM has dipped below US Airways' is its impressive labour cost reduction; in terms of non labour CASM, US Airways was 12% below Northwest — a differential that Northwest attributes to its larger international network and premium revenue–related costs.

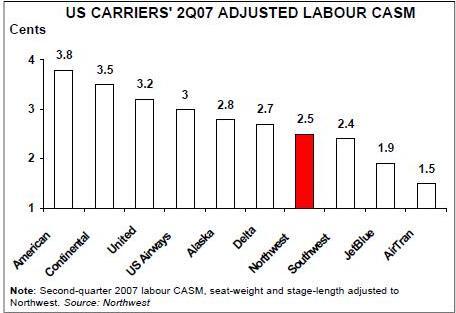

Northwest has transformed its labour cost structure from the highest to the lowest among the network carriers. Its second quarter seat–weight/stage–length adjusted labour CASM of 2.5 cents was a whopping 34% below American’s 3.8 cents, 17% below US Airways' 3 cents and 7% below Delta’s 2.7 cents (see chart, below).

The most exciting thing about Northwest is that it is likely to increase its cost advantage in the coming years. This is because of its aggressive fleet renewal, long–term labour contracts, growing use of low–cost regional subsidiaries, potential cost savings in combining wholly–owned regional units and the restructuring of the cargo business.

Northwest does not have any labour contracts become amendable until the end of 2011, in theory giving it the longest labour respite among the major carriers. However, if American’s pilots succeed in getting hefty pay increases next year, the other legacy pilot unions may demand to reopen their contracts before amendable dates, especially if the industry remains profitable. ALPA has officially adopted the position that the concessions negotiated by several carriers in bankruptcy must be rolled back.

Furthermore, the recent adjustment to the Northwest pilot contract and possible new actions by an unhappy workforce may significantly dilute the cost savings. In the summer, to restore operational reliability, Northwest had to grant its pilots new performance bonuses, reinstate premium pay of 50% for pilots flying more than 50 hours a month and boost new pilot hiring. The pilot sickouts happening so soon after the Chapter 11 exit does not bode well for the future.

On the revenue side, Northwest has been a solid RASM performer because of its strong network and hubs, dominant position in key markets and lesser LCC exposure. The network, fleet and product improvements instigated as part of the restructuring led to a healthy 12% unit revenue improvement last year. Northwest had the industry’s fourth highest seat weight/ stage–length adjusted RASM in 2006 (10.8 cents), similar to American’s but some 6% below United’s and Continental’s.

Because of the recent restructuring, Northwest (like Delta) is expected to continue to enjoy slightly stronger RASM trends than competitors in 2008. The process will be helped by customer service enhancements, a $50m investment in product improvements this year and a major new front–line employee training initiative launched this autumn.

The five–year business plan that Northwest prepared in Chapter 11, which predicted continued strong profitability through 2010, was always considered more realistic than Delta’s plan, because Northwest’s plan relied mainly on cost cuts that were already in place rather than forecast revenue gains. However, with oil prices exceeding $90 a barrel, the plan forecasts (which assumed $65 oil) are no longer realistic.

That said, because of its cost advantage and better CASM and RASM outlook, Northwest is likely to outperform its peers profitability–wise in the next couple of years. It will earn excellent profits if economic fundamentals remain strong; it is also among the best positioned carriers to face a downturn or continued high fuel prices.

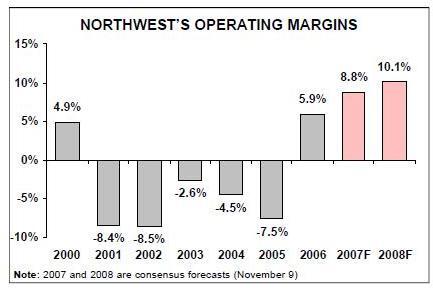

Currently, in the absence of any evidence of slowing demand, and assuming that oil prices moderate somewhat in 2008, Northwest is heading for strong profits in 2007 and 2008. The consensus forecast (as of November 9) is a net profit of $2.01 per share, or about $440m, this year, followed by $2.06, or about $540m (on a higher share count), in 2008. Operating profits are projected to rise from last year’s $740m to around $1.1bn this year and $1.3bn in 2008 (5.9%, 8.8% and 10.1% margins, respectively, see chart above).

After reducing this year’s planned capacity growth twice in recent months, Northwest expects its total ASMs to inch up by just 0–1% in 2007 (domestic down 2–3%, international up 4–5%). Despite that, ex–fuel CASM is still expected to decline by 2–3% this year, in line with the business plan fore–cast.

Northwest has not yet released its capacity plan for 2008. Like its peers, it does not have meaningful fuel hedges in place for 2008. However, Northwest does have significant fleet flexibility to respond to changing industry conditions.

Deleveraged balance sheet

Northwest was able to reduce its debt and lease obligations by $4.2bn in Chapter 11, from $13.5bn to $9.3bn (net debt and leases were more than halved from $12bn to $5.8bn). This involved eliminating $1.7bn of unsecured debt, cutting lease obligations by $2bn and reducing aircraft debt by some $500m. In addition, Northwest refinanced $2.25bn in secured bank and aircraft debt (achieving significant interest cost savings) and raised $750m in equity through a rights offering.

As a result, Northwest has one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry. At the end of June, its lease–adjusted–net debt/ EBITDAR ratio of 3 times ("net" meaning after the deduction of cash reserves) and its lease–adjusted–net–debt/capitalisation ratio of 49% were very similar to Delta’s ratios (2.9 times and 48%), which were the lowest in the industry excluding Southwest. Using the more common measure, Northwest’s lease–adjusted–total–debt/capitalisation ratio of 61.6% was also among the lowest in the industry.

The balance sheet improvements have earned Northwest the highest credit ratings among the network carriers. Back in May, S&P issued Northwest a B+ corporate rating and Moody’s a B1 rating, both with "stable" outlooks.

While in Chapter 11, Northwest successfully restructured its pension liabilities, which totalled $3.1bn pre–bankruptcy. By freezing its defined–benefit plans, replacing them with defined–contribution plans and taking advantage of the new rules that permit an 8.85% discount rate and amortisation of the pension liability over 17 years, Northwest has reduced its annual cash contributions to a very manageable $80- 100m.

Northwest had an ample $3.1bn in unrestricted cash, or about 25% of last year’s revenues, at the end of September. The airline also had $739m in restricted cash, including $213m related to a pending investment in Midwest Airlines. Year–end unrestricted cash reserves are expected to amount to $2.8–2.9bn.

However, Northwest will not be able to sustain its leading financial ratios because of its aircraft spending commitments. In comparison, American and United have very modest capex requirements and are also currently focused on paying down debt. From next year onwards, Northwest will probably find itself in the middle or bottom half of the Legacies' net–debt/EBITDAR league.

Northwest anticipates $4.1bn in aircraft capital expenditures in 2007–2010, or about $1bn per year, plus $200–250m in non–aircraft capex annually. Debt maturities are running at $400–600m annually in the next four years. The airline believes that all of that is manageable; management noted that the aircraft spending will actually be below the $1.5bn annual average aircraft capex seen in 2001–2005.

Previously aircraft capex was expected to peak sharply in 2008 ($1.9bn), but the 787 delivery delays have reduced next year’s aircraft spending by $700m to $1.2bn. The $700m spending will presumably now be incurred in 2009, which previously had only $467m of planned aircraft capex. Incidentally, according to the management, Northwest is not entitled to penalty payments from Boeing for the delivery delays.

All of the new aircraft on order carry manufacturer backstop financing, but obtaining more attractive permanent funding should not be a problem, given Northwest’s improved balance sheet. Last month the airline demonstrated its ability to tap the public capital markets by raising $454m through EETCs to fund 27 Embraer 175LRs for its regional subsidiaries, despite the more difficult credit market since the summer.

In the event of continued $90–per–barrel of oil, a severe demand downturn or a worsened revenue environment, Northwest could always ground or accelerate the retirement of its unencumbered DC9s. Although Northwest will reap great economic benefits from new aircraft, if absolutely necessary, it should also be able to easily defer new aircraft deliveries or sell those slots to third parties.

Profitable re-fleeting

Northwest made many beneficial fleet moves in Chapter 11: restructuring 330 leases to market rates, rejecting 71 aircraft (including nine DC9s), accelerating the retirement of uneconomical aircraft (DC- 10s, 747–200s and Avro RJ–85s), reaffirming A330 and 787 purchase agreements and placing new orders for 72 76–seat regional jets.

Although Northwest still operates 103 DC9s, it has made great progress in shedding its other older types. In 2001 the fleet still included 40 DC–10s and 21 747–200 passenger aircraft; the last 15 DC–10s were retired during Chapter 11 and the last two 747–200s went last summer.

Having missed the US legacy sector’s last fleet replacement phase, Northwest is now in the middle of a $6bn renewal effort. The programme has added 32 A330s and will involve the acquisition of 72 Bombardier and Embraer regional jets and 18 787s. Northwest calculates that these aircraft purchases have a collective forecast return on investment in excess of 15%.

Northwest has now taken all of the firm A330 deliveries, following the arrival of the 32nd aircraft in October. The type has replaced DC–10s on European routes (with the help of ten 757s on the thinner routes) and DC–10s and 747–200s on the Pacific (with the help of some 747–400s). Northwest now boasts the world’s largest A330 fleet and the youngest transatlantic fleet in the industry.

The 787 Dreamliner will be Northwest’s pride and joy, the backbone of its international fleet. CEO Doug Steenland said recently that when placing the original launch order in June 2005, the airline worked with Boeing to forge a purchase agreement that could anticipate and survive a Chapter 11 filing. The deal — 18 firm orders and 50 options, at favourable launch customer prices — was reaffirmed in October 2006.

The 787 will be used to further optimise Northwest’s Pacific network and develop new markets, including nonstop service to China. The 787–8 (the standard 200 seat version) would make it from Detroit to cities such as Mumbai, Delhi and Shanghai; the 787–4 (403 seats) would make it to all of Europe, Beijing, Seoul and Tokyo; the 787- 9 (241 seats) would also make it to Johannesburg, Taipei and Hong Kong. The 787 will also provide opportunities to rationalise 747–400 service, improving pretax margins by as much as 15 points in some markets.

Production problems at Boeing have delayed Northwest’s first 787 deliveries from August 2008 to the first quarter of 2009. The airline said that it was disappointed but that it could adapt; for example, it might launch its planned Detroit- Shanghai route with 747–400s. Northwest noted that it would have the 787 well–ahead of the Pacific’s 2009 peak summer season and that later 787 deliveries might not be delayed as much.

Northwest is the only US major that operates dedicated 747 freighters. Although the 13–strong fleet is old, the airline does not anticipate any fleet changes or additions in the coming years.

The A330 and 787 orders illustrate that, like many of its peers, Northwest currently focuses on growing internationally. Its international fleet will expand from 43 aircraft in 2005 to 73 by 2010.

The Bombardier and Embraer RJs ordered in October 2006 — 36 CRJ900s and 36 E175s, delivering between June 2007 and December 2008 — are the key component of Northwest’s domestic rightsizing effort. The 76–seat aircraft, to be operated by subsidiaries Compass and Mesaba, will complement and replace 50–seat CRJ200 and 100–seat DC9 flying at Northwest’s hubs. The aircraft are optimally sized, have first class cabins and offer range flexibility to serve a variety of markets. Northwest expects the RJs to offer a significant 16- point pretax profit margin advantage in markets where they replace DC9s.

Northwest split the order seemingly because it wanted to both build on its long term relationship with Bombardier and benefit from the E175’s superior 1,700–mile range (compared to the CRJ900’s 1,400 miles and the DC9’s 1,000 miles).

The RJ strategy is possible because Northwest’s mainline pilots agreed to relax their scope clause to allow up to 90 76- seat RJs at regional partners. The deal did not go as far as had been hoped (and does not compare favourably with other legacy carrier scope clauses), but it was a good start.

Northwest’s next major fleet decision will be the DC9 replacement. Around two thirds of the 103 DC9s are 35 years old. The DC9 fleet will still be sizeable at the conclusion of the 76–seat RJ deliveries at the end of 2008. In any case, Northwest will need a 100–seater, which it will fly at the mainline. But while there have been discussions with Bombardier and Embraer on 100–seaters, the decision may not come anytime soon — among other reasons, because it may be beneficial to wait for new–technology aircraft. JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker suggested in a recent research note that the future order could be for the Bombardier C–series aircraft and worth close to $3bn.

Network strategy and plans

Northwest’s basic aim is to make the most of its unique network assets, which have enabled it to develop a powerful market position domestically and on US–Asia routes. The airline has a strong domestic franchise, with the number one position and 24% revenue share in Heartland (the Upper Midwest region), thanks to its strong hubs in Detroit, Minneapolis/St. Paul and Memphis. Northwest is also the largest US carrier on the Pacific, with a hub at Tokyo- Narita and valuable beyond–Tokyo fifth freedom rights.

However, in the short–to–medium term at least, Northwest is not the same spectacular international growth story that Delta is; its international growth is likely to be in single digits. The aggressive fleet plans are essentially for replacement and long term growth.

Northwest differs from its legacy peers in two significant respects. First, it has embraced international alliances to a much greater degree, as evidenced by its old–established partnership with KLM, membership of SkyTeam and plans to develop a four–way transatlantic JV with KLM, Delta and Air France. This has helped compensate for shortcomings in its route network; for example, the Northwest/KLM combination generates $3.5bn in annual revenues, making it the fourth largest (and highly profitable) transatlantic carrier.

Second, Northwest operates 747 freighters and earns 8% of its revenues from cargo — unusual in the US context but, of course, totally in line with what global carriers elsewhere are doing.

Northwest’s network restructuring in the past two years has featured a domestic to international shift, though nowhere near as sharp as Delta’s. Between 3Q05 and 3Q07, mainline domestic passenger revenues remained unchanged, while Pacific and Atlantic revenues rose by 8.7% and 13.5%, respectively (to account for 24% and 16% of total mainline passenger revenues; the remaining 60% is domestic).

Domestic plans: The focus will be on a mainline–to–regional shift with the help of the 76–seat RJs. Regional growth is expected to be in the mid–teens. Having restructured its regional partnerships, Northwest is looking to develop synergies between its wholly owned subsidiaries. In the past year, Northwest has acquired its partner Mesaba and launched a new wholly- owned unit Compass. Mesaba will operate the new CRJ900s and Compass the E175s. The third regional partner, 12%- owned Pinnacle, will continue to operate 50–seat CRJ200s for Northwest.

Northwest is in the process of purchasing a $213.3m, 47% passive stake in Midwest Air Group as part of TPG Capital’s $451m acquisition of the Milwaukee–based carrier; the transaction is expected to close by year–end. The two airlines have code–shared for some time and are now expanding that and exploring other forms of cooperation. Midwest will help solidify Northwest’s Heartland position; however, the main benefit is to prevent low–cost carrier AirTran, which was previously aggressively bidding for Midwest, from gaining a foothold in the region. Since TPG will want to exit in due course, Northwest may end up as the majority owner of Midwest.

Atlantic: Northwest has continued to grow on the Atlantic as part of its alliance with KLM, which has been in place since 1991. This past summer saw the addition of new daily nonstop 757 Detroit- Düsseldorf and Hartford–Amsterdam flights. In spring 2008 Northwest will introduce Minneapolis–Paris and Portland- Amsterdam routes, while KLM will add an Amsterdam–Dallas service.

In a solid response to the US–Europe open skies treaty, in June Northwest and fellow SkyTeam members Air France, Alitalia, CSA Czech Airlines, Delta and KLM applied to the DOT for antitrust immunity for transatlantic routes. Currently, Delta has antitrust immunity with Air France, Alitalia and CSA, while Northwest has it with KLM. Included in the application is a four–way joint venture agreement between Northwest, KLM, Delta and Air France that would facilitate deeper KLM/NWA–style commercial integration. In mid–October the DOT made its first move: setting a timeline for consideration of the application. One Wall Street analyst suggested recently that the airlines have a "fair shot" at receiving the immunity.

Pacific: Northwest has one of the world’s largest Pacific route networks. The operations focus on Tokyo Narita, as Northwest has unlimited fifth freedom rights from Japan to the rest of Asia. While United also has fifth freedom rights out of Japan, Northwest has 50% more slots at Narita — a total of 376 permanent weekly slots, the most for any non–Japanese carrier. Northwest uses those slots and rights to link nine US gateways and 12 Asian destinations via Tokyo. In addition, Northwest flies nonstop from Detroit to Osaka and Nagoya and uses its fifth freedom rights to serve points such as Guam and Honolulu from those cities.

But competition is growing on the Pacific, particularly in the lucrative USChina market. Those routes have become a focus for most of the large US carriers as the ASA is being progressively expanded. Under the latest US–China deal signed in July, flights between the two countries will be increased from the current ten per day to 23 by 2012. The US side will get two additional daily flights in 2008, four more in 2009, three more in 2010 and two more in 2011.

Competition for those rights has been fierce. So far, the DOT has awarded the two new 2008 flights to Delta and United, while American, Continental, Northwest and US Airways have been tentatively selected for the 2009 additions. Northwest plans to launch Detroit–Shanghai in March 2009 — its first nonstop service to China. Northwest has also sought Detroit–Beijing authority, which it may get in later years.

Northwest remains well positioned to maintain its leadership position on the Pacific for two reasons. First, it will have the perfect long–range aircraft for Pacific nonstop operations. In addition to Japan, the airline expects to utilise the 787 on new routes to China, Korea, etc.

Second, Northwest may in the future take advantage of its Tokyo slots, fifth freedom rights and special provisions in the US–China ASA to launch service from Tokyo to secondary cities in China, using smaller aircraft such as the 757s. A large number of cities in China have no slot or frequency limitations under the US–China bilateral, because the Chinese government wants to encourage flights to under–served airports. Cities such as Chengdu, Changchun and Dalian are not large enough to justify nonstop service from the US, but they still have sizeable populations (3–6m, plus many times more in their potential catchment areas), and Northwest could aggregate traffic in Japan coming from all of its US gateways. In the third–quarter conference call, Northwest’s management described the secondary Chinese points as a "very interesting economic opportunity for us".

Cargo: Northwest’s cargo business, which generates $900m in annual revenue, with 80% coming from US–Asia services operated through hubs at Anchorage and Tokyo, has under–performed the rest of the network in recent years. There have been reliability, product quality and profitability issues. Northwest is now trying to fix those problems; the measures including relocating maintenance facilities, changing the top management, improving revenue management and eliminating some marginal flying.

Opportunities for value creation?

The management indicated in the third–quarter call on October 29 that Northwest sees industry consolidation as inevitable and offering significant opportunities for value creation. Noting that the company is committed to maximising shareholder value, CEO Doug Steenland stated: "This commitment, together with Northwest’s non–replicable strategic and network assets, our competitive cost structure, our strong earnings and our very strong balance sheet will make Northwest a key participant in any future industry developments".

But Steenland also stressed the need to take into account the many "execution risks" in mergers, including the "requirement to negotiate labour agreements, which would likely lead to cost increases", when deciding whether a deal was in the best interests of Northwest’s constituents. It would be a shame if Northwest lost its hard–won cost advantage through M&A.

The key point is that Northwest is well positioned for any industry scenario — independent survival or consolidation.

Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl suggested in mid–September that Northwest had positioned itself for possible consolidation as either a buyer or seller, though its strong balance sheet and unique network assets made it an attractive acquisition target.

While Northwest would be a good fit with a number of airlines, Delta remains a favourite, based on potential network synergies, an existing commercial alliance (established in 2002 and also including Continental) and links at the leadership level (since Northwest’s former CEO Richard Anderson took over at Delta in September). Another favourite is longtime partner Continental. Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg suggested in an early- October research note that the "golden share" Northwest holds in Continental represents "tremendous strategic value" in the event of industry consolidation.

Separately, like many of its peers, Northwest is currently analysing the potential of spinning off various assets, including its WorldPerks FFP. In 2003 Northwest sold most of its regional unit Pinnacle in a $272m IPO; it now retains only a 12% stake in the carrier. The two wholly–owned regional units, Mesaba and Compass, are obvious future spin–off candidates.

| No. of | Firm | |

| aircraft | orders | |

| A319 | 57 | 5 |

| A320 | 73 | 2 |

| A330-200 | 11 | |

| A330-300 | 20 | 1 |

| 787-8 | 18 | |

| 757-200 | 55 | |

| 757-300 | 16 | |

| 747-400 | 16 | |

| 747F | 13 | |

| DC9 | 103 | |

| Total mainline | 364 | 26 |

| CRJ200 | 141 | |

| Saab 340 | 49 | |

| CRJ900 | 7 | 29 |

| E175 | 3 | 32 |

| Total regional* | 200 | 61 |

| TOTAL FLEET | 564 | >87 |