America West: "an LCC in Network clothing"

November 2003

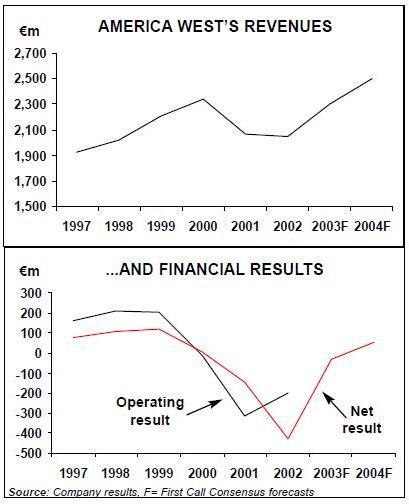

After being rescued from the brink of bankruptcy by the US Air Transportation Stabilization Board (ATSB) in January 2002, America West Airlines has staged a surprise turnaround this year. The Phoenix–based carrier — now the eighth largest major — has been outperforming its peers by a wide margin on both the cost and revenue fronts. It is now expected to return to decent profitability in 2004 — well ahead of the "top six" carriers, the best of which (Continental) is only likely to break even next year.

Most significantly, America West has succeeded in something that the large network carriers have failed in so far — revamping its fare structure in such a way that the impact is not just to pull in business traffic but to boost total revenues.

In other words, AWA is the first of the old school network carriers to transition to an LCCstyle simple, low fare structure.

It has retained its full service and its low cost structure. JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker recently very aptly described it as "an LCC in Network clothing".

How has America West accomplished such a transition? Its smaller size and more niche–type network obviously makes it easier to implement radical fare structure changes, but could the other network carriers still learn from it?

AWA has been NYSE’s top performing stock this year, rising steadily from around $2–2.50 in April to almost $15 at the end of October.

Most analysts feel that the stock has considerable further appreciation potential, given that it is still trading more like a network carrier (with a valuation less than 10 times expected 2005 earnings) than an LCC (up to high–20s, with JetBlue’s recent 30–plus regarded as excessive).

It is worth noting that in late October Standard & Poor’s equity research group added AWA to its top ten portfolio — that is, the ten US company stocks (not just airlines) considered to be the best candidates for capital gains over the next 6–12 months.

There is buzz about AWA also because it is now starting to grow again. It has just introduced its first point–to–point transcontinental flights, to supplement service from its Phoenix and Las Vegas hubs, and plans to grow ASMs by 10% in 2004. Inevitably, given the business model transition, there is speculation of a "Southwest–style" sustained growth strategy. However, there are potential problems in at least two areas. First of all, unlike Southwest and JetBlue, AWA has an over–leveraged balance sheet, with a lot of extremely expensive debt and a heavy operating lease burden. This poses risk particularly if the economy weakens and may make it hard to fund expansion.

Second, given Southwest’s already significant presence in AWA’s two hubs and on the West Coast, and given the multitude of strong LCC upstarts that (in addition to Southwest) are now expanding rapidly on the East Coast and in some coast–to–coast markets, where exactly will AWA grow?

Great turnaround story

America West has always been a bit of an oddball, not fitting neatly into any industry category.

Founded in 1983 (celebrating its 20th anniversary this year), it is the only post–deregulation new entrant that has achieved "major carrier" status of $1bn–plus annual revenues (JetBlue is just about to become the second).

AWA emerged from a three–year Chapter 11 reorganisation in August 1994 in great shape, with low unit costs and a strong balance sheet.

In the late 1990s it grew rapidly and began to suffer operational problems and lagging staff morale. When those problems worsened and also fuel costs surged in 2000, AWA’s profits almost disappeared. Consequently, after two years of weakening financial profile, it had only $80m in cash at hand and no available credit facilities when the current crisis hit the industry. A $200m private financing that AWA had lined up collapsed in the wake of September 11. When major debt and lease payments came due in January 2002, in the absence of a rescue package the company would have had to seek Chapter 11 protection from creditors.

Subsequently, AWA became the first airline to be assisted by the $10bn federal loan guarantee programme (see Aviation Strategy, December 2001 and January 2002). It secured a $419m term loan ($380m covered by guarantees), which enabled it to avert Chapter 11 and obtain $600m of financial support and concessions from its key business partners.

The airline sold itself to the ATSB as a success story of deregulation, arguing that with its low cost structure and substantial hub and spoke operations, it keeps price discipline in place across the rest of the industry. However, the ATSB was not unanimous in its decision to grant the loan guarantees, and it imposed rather onerous loan terms.

The board considered that the AWA proposal presented a "significant risk of default", while many analysts cautioned that the airline still faced considerable hurdles in restoring financial viability.

Now the airline is obviously becoming a real ATSB success story — not just because it is surviving but because it is also having more impact than ever before, thanks to the low fare transition. CEO Douglas Parker made the intriguing point recently that the US government could collect a serious windfall profit at any time if it chose to exercise and sell the 18.75m/$3 warrants it obtained in AWA as part of the January 2002 restructuring. For example, at the late October share price of $14, US taxpayers would have benefited to the tune of $200m — and that would be on top of the hefty fees that the government is collecting on the loan guarantees.

(The government has another eight years to exercise the warrants. It cannot hold the shares; if it exercises the warrants, it must sell.)

Similarly, the other parties in the restructuring that received stock–based compensation for their sacrifices also stand to gain handsomely.

AWA issued some 3.8m warrants to other loan participants and about $100m of seven–year debentures convertible into shares at a price of $12 to its aircraft lessors (the latter can not be converted until early 2005). AWA has now reported two consecutive quarterly profits. In the first nine months of 2003, it earned a small operating profit of $20.3m (1.2% of revenues) and a net profit of $50.6m, compared to operating and net losses of $122m and $336m respectively in the same period in 2002. However, there will be losses in the current (seasonally weakest) fourth quarter.

AWA’s leadership is predicting a loss for full–year 2003, but the figures really do not add up and some analysts have suggested that the result is more likely to be a small profit or break–even. That would be a significant achievement, as only a handful of LCCs in the US will report profits for 2003.

In late October analysts expected AWA to earn between 75 cents and $1.40 per share (roughly $45–80m) before special items in 2004, but the past six months have seen a continual upward revision.

Douglas Parker attributes the financial turnaround to three elements. First, as the cornerstone, the earlier operational reliability problems have been rectified. Second, the pricing structure that was put in place in early 2002 has been an "enormous success".

Third, AWA’s cost controls have been "much better than industry average".

Retaining a low cost structure

Despite the problems that it had in the 1990s, AWA managed to keep its costs low in those years. Although unit costs rose sharply between 1999 and 2001, from 7.52 to 8.82 cents per ASM, aggressive cost cuts and controls (with considerable help from the January 2002 restructuring) have brought them down to the 8–cent level in 2003. This is the second lowest among the majors (after Southwest). The stated aim is to "maintain position as low–cost leader among the major airlines".

The airline recorded an impressive 5.1% decline in ex–fuel unit costs in the third quarter, thanks to additional cost cuts announced and implemented in the spring. The biggest (and toughest) of those was the decision to close the unprofitable Columbus hub. Other recent measures have included a large reduction in the size of the management team, maintenance cost initiatives and further cuts in distribution costs.

The Columbus hub had originally been established to enhance presence in the East, but direct flights to the East Coast from Phoenix and Las Vegas had made it redundant and it was losing $25m annually. The downsizing, completed by mid–June, involved phasing out 12 RJs and ending a feeder relationship with Chautauqua.

The Columbus operation was reduced from 49 daily flights to just four daily mainline flights to the two hubs. AWA did not need to negotiate labour concessions as part of the ATSB deal, because its labour costs were already well below industry average. However, it had to make a seven–year commitment to holding down labour costs.

If for any year actual unit labour costs exceed the business plan estimates submitted to the ATSB, AWA will have to partially prepay the loan.

Contrary to initial fears of labour strife, AWA has not had any real problems (aside from difficult contract negotiations with ALPA). The situation brightened considerably in late October when the pilots, who rejected a tentative deal in late 2002, agreed to a new tentative three–year contract (subject to a ratification vote this month).

Terms were not disclosed, but AWA’s leadership estimated last month that a new pilot contract would add to costs by about $30m annually.

The airline also has to negotiate new contracts with its dispatchers and mechanics, whose contracts are already amendable, and with the flight attendants, whose contract becomes amendable in April 2004. It will all be tougher when profitability is restored, but the aim is still to keep overall unit costs flat.

New fare structure impact

AWA’s unit revenues (RASM) have traditionally been among the industry’s lowest, because it has focused on leisure traffic and competed against Southwest at its hubs. But over the past 2–3 years the airline has been outperforming the industry in RASM and therefore closing the revenue gap.

Progress on that front has been rather spectacular in the past six months. In the third quarter, despite a 5% higher average stage length, AWA’s passenger unit revenues (PRASM) rose by 14.3%, compared to the majors' average of 9.4%, and AWA’s yield was up by 7.3%. Furthermore, according to its leadership, the rate of AWA’s industry out–performance has been increasing month by month, with October PRASM again showing a greater differential.

This was attributed to two factors. First, AWA is detecting a continuing shift of business travellers to its simplified fare structure and full service amenities. As evidence, business traffic’s contribution to its total revenues has surged to 44% from 34% a year ago — a trend that contrasts sharply with what the top six carriers have reported.

Second, AWA’s PRASM has risen significantly because of its aggressive "peak day yield management strategy".

America West reformed its fare structure in March 2002, in what it said was a response to business travellers' demands. The airline introduced a simple, flexible pricing structure nationwide, with no Saturday night stay requirement and one–way fares 40–70% lower than competitors' walk–up or 7–day advance purchase fares.

The new structure was similar to what AirTran, ATA and other LCCs have adopted. It was much broader and entirely different from the limited pricing experiments that the larger majors had conducted up to that date (or since then).

The fare structure received an unenthusiastic response from analysts, who worried about competitive response — and had perhaps already seen too many fare experiments that had had negative or only neutral impact on the bottom line.

However, AWA says that competitors have matched its prices in inventory control buckets (calling it a "limited match").

There have been no further hostile responses, probably because the airlines already discount so heavily in the current extremely weak revenue environment.

AWA seems to have found a fare structure that is paying off in terms of improved revenue generation. The formula works for AWA probably because, as a leisure–oriented carrier, it did not have significant business segment revenues to lose in the first place.

Growth plans

AWA has not shrunk in size during the current industry crisis — another characteristic that sets it apart from the top six carriers.

There was a modest 2.1% ASM decline in 2001, but that was recovered last year and this year capacity is growing by 2–4%.

Plans now call for ASM growth to be stepped up to 8–10% in 2004. About half will come from increased aircraft utilisation and the other half from fleet additions. There are currently only two firm deliveries scheduled for 2004 — one A320 and one A319 — but AWA expects to lease another 3–5 aircraft by mid–year. AWA has just added a new element to its route network strategy, to supplement the traditional hub and spoke model.

In October, it introduced its first point–to–point transcontinental services, linking Los Angeles with Boston and New York JFK.

This will be followed by service from San Francisco to those cities over the next few months. The airline is evaluating other similar markets for next year’s growth plans, while continuing to grow the Phoenix and Las Vegas hubs. In January it is substantially boosting service between Las Vegas and nine West Coast cities.

The sudden ramp–up of growth and the new high–profile routes seem risky strategies so soon after the company’s financial restructuring and the fare structure revamp. But AWA considered the opportunities too good to be missed, describing the market as "one of the last bastions of extremely high point–to–point fares".

It had the advantage among the LCCs of actually having aircraft that could fly those routes — AirTran, by contrast, will have to wait till next summer for its 737–700 deliveries to commence. "We got in while we could", the AWA executives said recently.

Also, none of those markets are totally new to America West. It has operated coast–to–coast services via Phoenix and Las Vegas since the late 1990s and already serves every one of the cities that feature in the point–to–point plans.

The new Los Angeles–East Coast flights have attracted strong forward bookings — perhaps not surprising in light of the fact that AWA is the first and only LCC on those routes (JetBlue operates Long Beach–JFK) and it entered the markets with 75% lower $299 walk–up fares. However, success will depend on winning business travellers from the top six carriers.

At this point AWA is not making any kind of growth commitment beyond 2004. However, if it wants to continue growing at a 10% rate, it will need to get more aircraft. JP Morgan’s Baker suggested in a recent research note that a new (A320–family) aircraft order is possible before the end of this year. Aside from point–to–point expansion, AWA has not indicated where it believes its best future growth opportunities might lie. Baker made the point that it lacks an "unpolished hub like Newark" (which has kept Continental busy) and that Phoenix and Las Vegas clearly have limits. He suggested possible future growth in the popular Western corridor (as Southwest continues to focus on the East) — AWA recent response to that was "not immediately". No doubt the airline is also waiting to see what happens at United and American.

AWA is finding it hard to forge new marketing relationships with the larger carriers these days because of the new fare structure (Continental cancelled its alliance the day that the new pricing was announced). But AWA is not too concerned as it believes that it has the best FFP among the LCCs because of its long–time relationships with BA and Northwest.

AWA built its cash position to a relatively healthy $584.5m at the end of September, up by $120.1m since the end of June in part thanks to $86.8m proceeds from a private convertible note offering. The aim is to maintain cash at that level, because there are debt maturities of $104m and $179m coming up in 2004 and 2005 respectively (mainly ATSB loan repayments).

The existing reserves and future cash generation from operations, supplemented by aircraft financings, are generally considered to be adequate to meet the financial obligations. However, given the high leverage and lack of credit line or unencumbered assets, there is no cushion against any economic or industry downturn.