US Airways: Will Chapter 11 help its long-term survival prospects?

November 2002

In August US Airways became the first — and so far the only — major airline to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the post–September 11 environment. Not much of a surprise because, even in the best of times, the airline never looked like a long term survivor because of its punitively high cost levels.

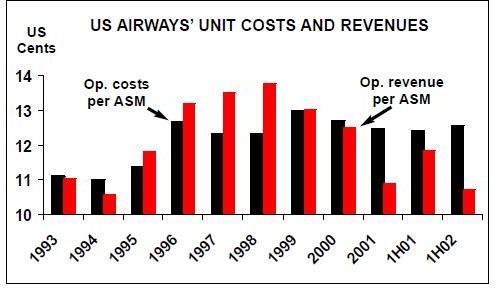

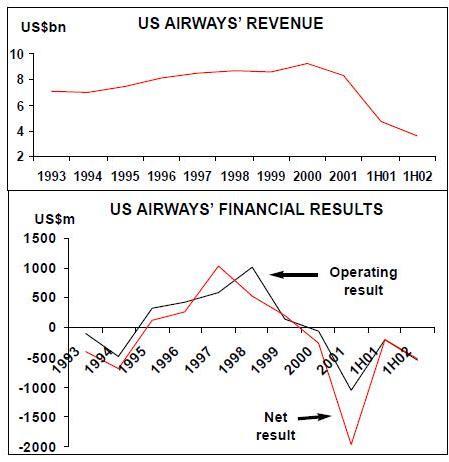

US Airways entered the current industry crisis in a weaker position than its competitors, because its financial profile began deteriorating long before September 11. Since the late 1990s, its yields have plummeted due to escalated low–cost competition on the East Coast, while its costs per ASM have remained in the 12–13 cent range. The company posted a $269m net loss already for 2000 and another $195m loss for the first half of last year.

The past 12 months have been disproportionately tough for US Airways because of its heavy exposure to the high–yield East Coast markets and focus on short haul operations.

The airline suffered also because of the closure and gradual opening of its main hub at Washington National (service was not fully restored there until May 2002) and continued loss of passengers to competitors' regional jets.

In recent presentations to creditors, the company has estimated that, over the past four years, low–cost carriers have almost doubled their share of East Coast capacity from 10.7% to 19.4%, while US Airways' share has fallen from 21.9% to 18%. Lowcost carriers now overlap with 40% of US Airways' revenues, compared with 24% in 1998.

The airline also estimates that regional jet (RJ) operations on the East Coast (defined as the area east of the Mississippi) have surged from 80m ASMs in 1998 to 469m ASMs this year, while the number of cities served with RJs has risen from 76 to 113. Competitors account for virtually all of that expansion, because until very recently US Airways had severe scope clause restrictions on RJ numbers.

US Airways also blames the failed merger with UAL, which might have addressed some of the issues by adding it to a global network. The DoJ failed to approve the merger in late July 2001 after reviewing it for almost 15 months, during which time US Airways was precluded from restructuring its operations as a stand–alone carrier.

After the merger fell through, US Airways quickly announced a staged, stand–alone restructuring under the leadership of the Gangwal–Wolf team. The plan, presented in August 2001, included measures such as elimination of MetroJet and the shedding of three fleet types.

That plan was, of course, pre–empted by the terrorist attacks. However, its existence did give US Airways a head start in dealing with the crisis, enabling it to achieve some post September 11 restructuring. Withinmonths, the carrier had, among other things, cut capacity by 23%, furloughed 20%-plus of its workers, discontinued MetroJet, parked 111 aircraft and deferred Airbus deliveries.

As things turned out, US Airways reported a staggering $1.97bn net loss (or $1.17bn before special items) for 2001 and a $269m loss for the first quarter of 2002. The pre–tax loss margins before special items were the industry’s worst.

Cash reserves had fallen from $1.08bn at year–end to $561m at the end of March. US Airways predicted that, without additional funds, a liquidity crisis was likely by this winter.

US Airways embarked on yet another major restructuring in May — this time under the guidance of its new CEO David Siegel, who had begun his tenure in March by strengthening the company’s management team.

The aims of the latest restructuring are the same as those identified by the Gangwal–Wolf team last year — to reduce the cost structure, operate more RJs and maximise the revenue potential of the East Coast franchise through domestic and international alliances. As a new twist, the plan called for the participation of all key stakeholders and applying for a government- guaranteed loan. The schedule was tight because the deadline for submitting loan guarantee applications was June 28.

Since then, in only a few months, US Airways has accomplished much in terms of restructuring and strategic initiatives. First, it has secured $840m of annual labour concessions from its unions. Second, it has persuaded its pilots to allow a significant expansion of RJ operations. Third, it has signed and begun to implement a code–share and global marketing alliance with United.

Fourth, with the bulk of the labour concessions already negotiated by the end of June, in early July US Airways obtained conditional approval from the Air Transportation Stabilization Board (ATSB) for federal loan guarantees to cover 90% of a $1bn 6.5–year private sector loan. This will provide liquidity and fund the restructuring plan. The ATSB confirmed after the Chapter 11 filing that the offer was still effective; however, the loan would now be used as Chapter 11 exit financing.

In contrast to the rough treatment extended to other applicants, the ATSB was uncharacteristically complimentary about US Airways' business plan. The board noted the "disciplined and comprehensive approach that US Airways brought to its restructuring" and that the proposal "is based on reasonable assumptions and includes substantial cost savings".

The loan guarantee offer was conditioned on the successful conclusion of all concessions talks (labour, as well as lessors, financiers and vendors) and on US Airways providing the government more compensation (such as warrants).

When filing for Chapter 11 on August 11, US Airways still had in excess of $500m in unrestricted cash. It had defaulted on some lease and debt payments, but all of those were what the company described as "strategic deferrals". US Airways made it clear that the main purpose of the bankruptcy filing was to restructure aircraft–related liabilities, as it had failed to secure voluntary concessions from its lessors and lenders.

DIP and equity funding

The positive attributes — the restructuring plan, early success in securing labour concessions and promise of a government–guaranteed loan — set the stage for a successful and potentially "fast–track" Chapter 11 reorganisation. US Airways has had two serious offers of DIP and equity funding. The initial one came from David Bonderman’s Texas Pacific Group (TPG), which helped Continental and America West out of Chapter 11 in the early 1990s, as well as Credit Suisse First Boston and Bank of America. The second one, which US Airways accepted as a better offer on September 26, came from the Retirement Systems of Alabama (RSA), a state–employee pension fund that is one of US Airways' largest creditors.

Since the RSA bid is subject to continuing due diligence and better or higher bids through mid–November, there are potentially more offers to come.

RSA topped TPG’s bid by $40m or 20%, offering to invest $240m for a 37.5% stake in US Airways when it emerges from Chapter 11. This would give it five of the 13 board seats. The pension fund is also foregoing transaction fees, saving another $10m over the TPG offer. Third, as part of the deal, RSA agreed to restructure $340m of aircraft debt obligations.

RSA has $25bn in assets, and it already held more in US Airways debt than it is now taking in equity. Under its longtime CEO David Bronner, RSA has ventured into many non–traditional areas, including TV stations and newspapers, as well as tourism related investments such as golf courses.

RSA is also providing a fully underwritten $500m DIP financing, made up of a $250m term loan and a $250m revolving credit facility. The bankruptcy court initially authorised the release of $300m of that funding (of which $75m was used to pay off the original facility), with final court approval expected on November 7.

The DIP lending appears less risky when considering that it is due to be fully repaid from the $1bn government–guaranteed loan upon emergence from Chapter 11. Moreover, the remaining $200m of the DIP funding will not be released until US Airways has secured unconditional approval for the loan guarantees from the ATSB.

In late October, US Airways disclosed that it had received a commitment for the $100m at–risk portion of the $1bn loan. The airline also said that the ATSB had conditionally approved the issuance of a guarantee to support the loan once the court had approved a plan of reorganisation. US Airways expects to file that plan in December and to emerge from Chapter 11 in March.

The interest of the top–tier banks, a respected leveraged–buyout firm and a state pension fund could be regarded as a vote of confidence in US Airways' restructuring plan and its longer–term survival prospects. The investors have to take a long–term view because the US major airlines are not expected to return to decent profitability until 2005 at the earliest.

After being ousted by RSA, TPG released a statement saying that it would continue to watch US Airways' progress "with interest". One analyst suggested recently that it may have turned its attention to "other similar interests" (a Chapter 11 filing from UAL is possible this month).

The new funding will provide US Airways with adequate liquidity for the near term, considering that it had more than $500m in unrestricted cash in August and that it will have reduced debt and lease payments in the future. However, Standard & Poor’s cautions that the cash reserves could prove insufficient in the event that the industry environment worsens materially (if there is a war with Iraq).

The long-term survival plan

The May 2002 restructuring plan called for $1.3bn of annual cost savings and $600m additional revenues, to convert a $1.3bn pretax loss into a "required" $600m pre–tax profit (representing a 6–7% margin). As a result of rising fuel costs and continued revenue weakness, the cost–cutting target was recently raised to $1.4–1.6bn. All of this adds up to a very impressive package, and the signs are that much of it will materialise.

Of the $1.3bn original annual concessions, almost $1bn was due to come from labour and the remaining $300m from lenders, lessors and suppliers. The airline hopes that most of the additional $100–300m cost savings would come from aircraft lessors. The extra revenues would come from code–share alliances and increased utilisation of regional jets.

The labour concessions are all in place. US Airways reached agreement with its five–unions for a total of $840m in annual savings over 6.5 years through modification of contracts.

This will mean a 20%-plus reduction in annual labour expenses. Remarkably, the airline got about 85% of the cost reductions it asked for — all on a voluntary basis, without having to use Chapter 11 provisions. In return, employees will participate in the airline’s financial recovery through equity and profit sharing plans. The unions will also get three board seats.

Because of the concessions agreed to by the workers, US Airways promised not to seek further contract changes during Chapter 11. However, it has continued to furlough staff. The workforce has been cut from 46,000 before the terrorist attacks to about 35,400 at present, and recently announced furloughs will reduce it to about 32,000 by next spring. US Airways is still in negotiations with its lenders and lessors about reductions in aircraft ownership costs. The talks focus on four Boeing models — the 737–300, 737–400, 757- 200 and 767–200 — where the objective is to reduce lease obligations to "competitive capital costs" and debt obligations to current appraised values. Recent presentations to creditors have emphasised the continued decline in aircraft market values and the high cost of re–marketing those aircraft.

In early October, as the 60–day protection from repossession afforded by Section 1110 expired, US Airways announced its decisions on various financing obligations. As expected, it affirmed all financings related to Airbus aircraft — which it intends to keep — and paid past due amounts. It rejected financings related to its grounded fleet of older aircraft plus 10 Boeing aircraft.

Early in the Chapter 11 proceedings, US Airways had gained court approval to walk away from leases on 57 aircraft that it no longer operated (including 737–200s, MD- 80s, DC–9s, Fokker 100s and Dash 8–100s) and 10 other Boeing aircraft (eight 737- 300/400s and two 757–200s). The airline is believed to be seeking to dispose of another 22 Boeing aircraft to right–size operations. The fleet size has declined rather dramatically: from 417 at the end of 2000 to about 300 at present. However, US Airways will not shrink very much further because, as part of the labour concessions agreements, it promised to operate at least 245 mainline jets.

US Airways is, of course, hoping to keep its longer–term Airbus order obligations. It has 37 A320–family aircraft on firm order for delivery in 2005–2009, plus 173 purchase rights and 72 options. There is also one A330–300 on firm order for 2007 delivery, plus 20 options.

The revenue benefits in US Airways' business plan will take longer to materialise, but the key components are in place. First, the airline signed a marketing agreement with United in July and, following the DoT’s recent approval, plans to begin code–sharing in early 2003. Annual revenue benefits are estimated at $200m when fully implemented, assuming no competitive response.

Second, US Airways has obtained permission from its pilots to operate up to 465 RJs, subject to certain restrictions. This represents a massive increase from the current ceiling of 70 RJs.

It is expected to keep its three hubs (Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Charlotte) and maintain high levels of service to New York LaGuardia and Washington National. It will also maintain high levels of service to Europe and continue expansion to the Caribbean and Central America.

US Airways' greatest strength is its solid route franchise. It is the largest airline east of the Mississippi, where 60%-plus of the US population resides. It accounts for 35% of industry revenues in that area followed by Delta (28%), Continental (8%), Southwest (7%) and American (4%). It dominates its hubs and is the largest or second–largest carrier in 77% of the cities that it serves.

Sceptics argue that, even after Chapter 11 reorganisation has narrowed the cost gap, US Airways will still have a hard time competing with the low–cost carriers that are expanding aggressively on the East Coast. However, Blaylock & Partners analyst Ray Neidl pointed out in a recent research note that if US Airways has competitive hubs, it does not have to be directly competitive in terms of costs with the point–to–point low–cost airlines.