Qantas: inheriting markets, not buying problems

November 2001

Qantas is the only international network carrier whose prospects have improved since September 11. It has seized the opportunity presented by Ansett’s bankruptcy to hugely increase its market share, sell a successful rights issue and re–equip its 737 operation. But will it be able to build on this new foundation?

Qantas has emerged as the survivor of the chaos of the Australasian market. To resume the situation: in 1999 Singapore Airlines attempted to buy Ansett mainly to secure domestic feed from the Australian market. It was repulsed by Air New Zealand which was able to increase its stake in Ansett from 50% to 100% and, it thought, gain essential extra mass to enhance its chances of success internationally.

Then two new low cost carriers — Impulse and Virgin Blue — entered the market, completely undermining Ansett’s and Qantas’s domestic profitability. Impulse itself also lost a great deal, and in May was taken over by Qantas.

Ansett’s losses were, however, on a different scale and exacerbated by public concern about the carrier’s safety performance. On September 13 Ansett went into administrative bankruptcy and its fleet was grounded. Its parent, Air New Zealand, would have been forced into bankruptcy as well had not the New Zealand government in effect re–nationalised the airline with a NZ$885m (US$370m) recapitalisation. In the process, SIA’s 25% investment in ANZ was wiped out.

In recent months just about every consolidation permutation involving the major Australasian players had been explored — SIA buying all of Ansett, divesting its stake in ANZ in which Qantas would then buy 49%; SIA increasing its 25% stake in ANZ to gain effective ownership; Qantas buying out Ansett; Qantas investing in ANZ; SIA investing in Virgin Blue and amalgamating with Ansett. In the end none of these restructurings took place (though Ansett 2 is evolving — see below). Qantas, perhaps more by luck than judgement, avoided buying the deep problems of existing carriers and instead inherited a lucrative market.

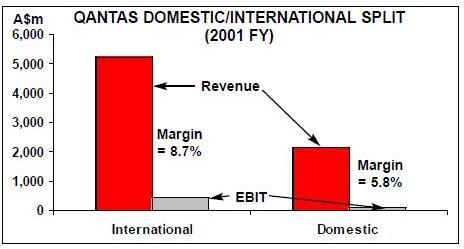

Qantas’s domestic market share shot up to 85% after Ansett’s demise, and its load factor got as close to 100% as is possible. Such was the lack of capacity in the Australian market that transcontinental services — Sydney–Perth — were being offered by SIA via Changi.

Fortunately, Qantas was able to shift capacity from its long–hauls which were obviously suffering in the post–September 11 market, redeploying 747–400s on domestic services. Qantas’s immediate reaction to September 11 was a reduction in services to the US from 31 to 28 a week, and temporary suspension of one service a week to India, Taipei and Jakarta.

Its public relations response to Ansett’s demise was also effective. Stranded Ansett passengers were given free seats up to September 27, and discounts were offered to Ansett passengers starting new journeys.

Rights issue

Qantas moved quickly to emphasise its determination to maintain a dominant domestic market share — not 85% evidently but a “sustainable” share of 65-70% by announcing a further fleet expansion (Qantas finalised its 10-year investment programme last November). The carrier stated that it expected aircraft to be available at “greatly reduced prices”, and targeted 737NGs and A320s for delivery during January-July 2002

Funds for the new equipment investment were partly provided by a rights issue towards the end of October, underwritten by UBS Warburg, Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank, which raised A$450m. Remarkably, this was 50% more than originally planned.

Qantas opted for the737-800, placing an initial firm order for 15 aircraft, with options on another 60.The first aircraft will be in service in January and the other 14 will be progressively introduced between February and July 2002.

In fact, the aircraft will come from the mega-order placed by its one world partner American, which clearly isn’t interested in deliveries in the near future. As expected, no price details were revealed but presumably Qantas will have benefited from a double discount — the first achieved by American as part of its “lowest guaranteed price agreement&rfquo; with Boeing, the second because Qantas is one of the very few airlines worldwide willing to take over deliveries at this time. In addition, American will assist Qantas with technical advice, simulator training, spare parts and engines.

The features of Qantas’s fleet operation will then be:

- The 737-800s forming the core of the narrowbody fleet, with an all-economy class configuration of at least 165 seats, operating on services where there is small or no demand for business class travel;

- Reconfiguration of a number of existing Qantas 737s to create a total fleet of about 40 all-economy class aircraft;

- Flights between Perth, Adelaide Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane operated by two-class 767s or A330s;

- Regular two-class 747 services between Perth and the east coast of Australia and on long haul leisure routes;

- A significant increase in direct flights between capital cities with fewer stops at ports in between; and

- An extension of the Cityflyer service, which currently operates between Sydney and Melbourne, to Brisbane. Qantas and American have also formalised a 10-year strategic alliance. This will involve:

- Qantas using American Airlines’ specifications as standard for the replacement of the Qantas 737 fleet, creating opportunities for short-term leasing between the airlines;

- Qantas progressively relocating to American’s terminal at Los Angeles airport;

- Qantas commencing Auckland-Dallas-Auckland non-stop services when the new, long-range 747-400 is delivered in late 2002;

- Expansion of the code-share agreement and FFP agreements between the two carriers. So it seems that Qantas has moved decisively to consolidate the transpacific route in a manner that complements its agreement with BA on the kangaroo route. Although American is in a weakened state at present, the oneworld combination with Qantas looks very well positioned to compete with United. The demise of Ansett removes competition from the Hong Kong and Osaka route and the threat of new competition on London, Los Angeles and Tokyo. SIA is weakened by Ansett’s collapse in that it has lost actual and potential feed from the key eastern seaboard market. It also seems to be at loggerheads with Virgin Atlantic over the role of Virgin Blue in the Australian market and other matters. Virgin Atlantic, itself, the other main competitor on Australia-UK services, is facing serious financial problems because of its exposure to the transatlantic market.

At the airline’s AGM in late October, Margaret Jackson, the Qantas chairman, made clear her view of the market she hopes Qantas will now be able to operate in: “In our view, it is critical that all participants draw the right conclusions from the Ansett situation. As an industry, we cannot afford to try and recreate the recent past of cut-throat competition. Nor can we afford to retreat to some distant past of heavy regulation, limited discount fares and costly government intervention.

“We need to accept that the Australian aviation industry of the future may look very different to that of the past. For example, Canada only has one national carrier. So does France. So do Germany, Italy and many other countries. Instead of two national carriers, competition can very effectively be sustained by a range of independent competitors focusing on particular market segments.

“We should prepare for a closer alignment between the Australian and New Zealand aviation markets. It was with this in mind several months ago that we sought to become a cornerstone shareholder in ANZ. Such a partnership made sense to us then, and it still does, but it could now be some time before a real market-driven solution is achievable”.

So, a future with Qantas as the sole international carrier of Australia and a potential take-over of ANZ, now greatly weakened and currently without top management.and pre-Ansett collapse.

The share price has also moved up from about A$2.9 just after September 11 to A$3.6 in late October. This capitalises the airline at A$4.8bn, which is roughly the same as BA, and BA of course owns 25% of Qantas.

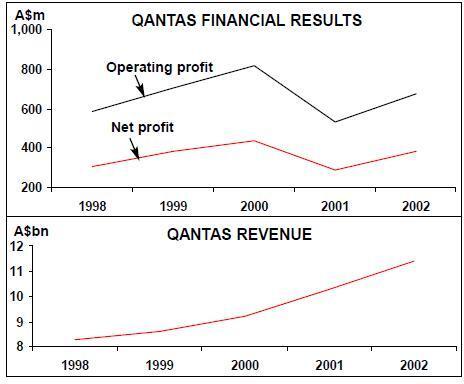

Looking further ahead the year to June 2003 holds the promise of not only a dominant domestic position but also a recovery in the international market. This, again according to Deutsche Bank, will produce a net profit of around A$509m (US$255m).

This sounds almost too good to be true given the recent turmoil in the Australasian market. The opposite, ultra-pessimistic viewpoint is that Qantas could end up like Air Canada, with a dominant market share but ever-deteriorating finances to the extent that massive government subsidies are being pumped in.

The most important difference between the two situation is that Qantas has managed to avoid the trap of buying out Ansett whereas Air Canada took over Canadian, and in the process bought union and cost problems plus totally uncommercial government restrictions on its freedom to manoeuvre — to drop unprofitable services and to lay off surplus employees.

Moreover, Virgin Blue is not quite WestJet, although it exudes confidence, has reported a marginal operating profit and has announce plans to expand its 737 fleet by three units to 15 by year-end (it had previously aimed for this total by end-2002).

Virgin Blue is estimated to have labour unit costs some 20% below those of Qantas, but some elements of a successful low-cost strategy may be missing. The airline seems

Financial outlook

The turn-around in Qantas’s fortunes is reflected in earnings forecasts. For example, Kevin O’Connor of Deutsche Bank is predicting a net profit of A$382m (US$190m) for the year ending June 30, 2002, compared to A$291m for 2001. This forecast, based on a domestic market share of 70-75%, is upgraded from A$300m pre-September 11

to be lacking a core market of routes from which it can expand — as WestJet has at Calgary or Ryanair has at Dublin and Stansted. It is taking on Qantas on trunk routes like Sydney-Brisbane and Brisbane- Melbourne, which means that it is faced with the same level of infrastructure costs as the flag-carrier. Virgin will undoubtedly expand on its pre-September market shares of around 12% but the Australian market does not seem to provide the opportunity of major cost savings through the use of secondary airports. Also, Virgin Blue has not gone for a strict one-type fleet — it will be operating 737-400s, -700s and -800s.

On the other hand, the airline is receiving strong government support in the form of start-up subsidies to enter new routes like Brisbane-Cairns and Brisbane-Darwin.

The other competitive uncertainty for Qantas is whether Ansett will re-emerge in some form. There are at least two proposals. The first comes from Ansett’s employees, and includes buying 35 planes and employing 7,000 workers from Ansett — the cost of a re-start-up is put at A$500m.

The second comes from two wealthy and locally well-known Australian investors — Lindsay Fox and Solomon Lew. Their venture includes buying and leasing 29 new Airbuses and employing some 4,000 staff, which more like European flag-carrier staffing levels that that of a low-cost lean competitor. The aim is to capture about 20% of the domestic market.

The Ansett 2 plan is costed at A$2.5bn of which about half would be equity. Given the record of Australian start-up attracting private capital will be difficult and institutional capital will also be reluctant if only because Qantas.

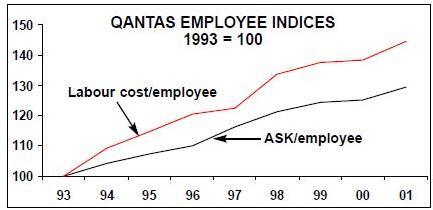

Qantas’s biggest threat may be internal rather than external. As the graph below indicates, Qantas’s unit labour costs continued to outpace productivity increase even during the period of intense domestic competition. Now Qantas appears to be willing to confront its traditionally very powerful unions. Its aim, it states, is to achieve a compatible cost base to its low-cost rivals. This will entail accept a wage freeze, flexible work hours and a ban on overtime. Exploiting the newly available pool of labour from Ansett may help Qantas achieve this aim.

It is also proposing launching a low cost subsidiary — named or re-named Australian Airlines — next April. This is a strategy that has been tried many times in the US and Europe but never with any great success.

The unions’ response has been traditional and ominous. The Australian Services Union, which represents more than a quarter of the airline’s staff, commented “The Australian civil aviation market is the one market that has the demand for seats and Qantas is ideally placed to meet that .... Virgin Blue’s costs didn’t take into account the discounter’s very different product aimed at the lower leisure market.”

The Australian Manufacturing Workers Union, the main union representing the mechanics, is possibly more militant, threatening strike action and complaining, “Qantas on their own admission are going to make hundred of millions of profit ... on that basis we cannot accept the wage cut they are proposing. A wage freeze is a wage cut.&rdquot;.

Qantas also has to be very wary of its government, which is determined to promote what it sees as a reasonable level of competition in the Australasian market. Qantas recent offer of a million discount seats elicited an immediate response from the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, which evidently suspected this of being a tactic to stall the growth of competitors. In the longer term it may well try to promote cabotage to encourage competition.

| In fleet | On order | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 737-300 | 16 | ||

| 737-400 | 22 | ||

| 737-700 | 15 | From American. Plus up to 60 options | |

| 747-200 | 4 | ||

| 747-300 | 6 | ||

| 747-400 | 25 | 6 | Long range version Del. 2002-06 |

| 747SP | 2 | ||

| 767-2/300 | 24 | ||

| A330 | 13 | Delivery 2005-05 | |

| A380 | 12 | Delivery 2006-10 | |

| Total | 99 | 46 |