JetBlue: justifying the hype

November 2000

JetBlue Airways, which began low–fare operations from New York JFK in February 2000, generated a great deal of hype because of its success in raising $130m in start–up funds. It had a strong management team and a promising growth niche. But sceptics argued that the carrier would not be able to attain Southwest’s cost and efficiency levels in the high–cost Northeast environment and with a much smaller fleet. And what about this year’s sharp hike in fuel prices? How could JetBlue possibly make viable a strategy that combines low fares with exceptional service quality?

Now in its ninth month of operation, JetBlue is rapidly proving the sceptics wrong. It has either met or exceeded all of its original financial targets. The company announced a "significant operating profit" for August — only its sixth full month of operation — and expects to post a profit for the second half of 2000.

The initial pro forma statements filed with the DoT in May 1999 envisaged profits for the last five months of 2000. But those forecasts were based on fuel prices of 60 cents per gallon, when East Coast carriers typically paid at least 100 cents.

As a privately owned carrier, JetBlue is not required to report financial data. But its leadership has indicated that while revenue generation has been stronger than anticipated, costs have also been below budget. CEO David Neeleman predicted in June that unit costs would be "something starting with a six" by the end of this year. This would be an amazing achievement with a (year–end) fleet of just ten A320s and at this year’s fuel prices. The April 1999 plan predicted unit costs of 7.39 cents per ASM — roughly Southwest’s level — when 11 aircraft are in operation.

Even though JetBlue has grown to a 10- city, nine–aircraft operation in eight months, it has avoided the hiccups and growing pains usually suffered by new carriers in their initial year of operation. This is in large part because the A320s have been extremely reliable. Also, and more surprisingly, the carrier seems to have suffered few ill–effects from ATC delays or the difficult weather conditions experienced along the East Coast this summer.

All of that was reflected in impressive operational performance statistics for the first six months of operation. Only ten flights were cancelled through August 31. JetBlue’s completion factor (99.8%) and on–time performance (80.3%) were three and seven percentage points higher than the averages for the major carriers in the first half of this year. The rates for mishandled baggage and involuntary denied boardings were only a small fraction of those of competitors.

JetBlue’s ability to achieve industry–leading operational reliability, low unit costs and profitability so early suggests that its management has found better ways of doing things. What factors or strategies explain this new entrant’s success? Could other carriers learn from it?

Promising growth niche

Many US new entrant carriers fail because they do not find markets that are large enough and have sufficient growth potential. There is no doubt that JetBlue has found a promising niche. JFK has an immediate catchment area of 5m people and can draw traffic from the tri–state area that has a population of 18m. Domestic traffic there has stagnated since the mid–1980s, as the entrenched major carriers have virtually eliminated price competition. Consequently, the over–priced and under–served markets have much pent–up demand.

JFK does pose many challenges — among them New York City area’s ATC and ground congestion, high cost of living, the airport’s relative distance from the city and lack of a rapid public transport connection. But JFK has been underutilised during a large part of the day, is undergoing a $9m redevelopment programme and will get a rapid rail link at some point in the future.

JetBlue should be able to generate substantial volumes of new traffic with its Southwest–style one–class, high–frequency service and fares of up to 80% below what was previously available. It may even be able to duplicate the famous "Southwest effect", which sees markets tripling or quadrupling within one or two years.

Strong political support

JetBlue would not be where it is today without the overwhelming local and national political support it has received since its inception. The carrier obtained its DoT fitness certificate in a record four months (though having the financial and other credentials obviously helped). It also received an exemption to the "high density rule" at JFK for an unprecedented 75 slots — all that it had sought.

The quest to become New York City’s first–ever homegrown low–fare airline obviously captured the imagination of local politicians. But JetBlue also smartly made a commitment to bring lower fares to upstate cities like Buffalo and Rochester (both are already served) and Syracuse (next year), which are among the 20 cities in the US with the highest average fares. This won it strong support from Washington politicians and legislators like Senator Charles Schumer and Congresswoman Louise Slaughter (among about 30 high–ranking officials specifically mentioned by the airline).

When the JFK slot award was announced in September 1999, Senator Schumer made this memorable statement: "JetBlue is the perfect airline to break the monopoly power which other airlines used as ransom to hold Upstate’s economy hostage. They are modern, well financed and committed to Upstate. It is a perfect fit for New York."

As an indication of continued political support, just a week after JetBlue’s launch, when competitors had (predictably) matched its fares, Congresswoman Slaughter urged Washington regulators to monitor the major airlines closely for any signs of predatory behaviour toward this new entrant.

While other US start–ups will find it hard to come up with plans that could inspire politicians to a similar extent, they can probably learn from JetBlue’s efforts on that front. David Neeleman said in a recent CNN interview that he learned to appreciate the importance of politics in the airline business at Southwest and that he continues to spend a lot of time with politicians. JetBlue also employs a full–time "VP Government Affairs" based in Washington DC.

Adequate capitalisation

Inadequate capitalisation is one of the main reasons why start–up carriers fail. JetBlue is uniquely well–funded by new entrant standards, having secured $130m in initial equity capital — at least four times as much as the best–funded of the previous new entrants had raised. Its prestigious backers include Chase Capital Partners (a venture capital arm of Chase Manhattan Bank) and venture funds controlled by New York–based financier George Soros.

Success on the funding front gave JetBlue two important advantages not usually enjoyed by new entrants. First, it was able to sign a contract Airbus to purchase up to 75 new A320s (the quoted price for the deal was $3.6bn, based on list prices, but JetBlue will have paid nowhere near that amount). Second, it has ample resources to weather competitive responses from the major carriers.

In September JetBlue secured a commitment for an additional $30m in equity capital from its existing investors, all of whom participated in their full pro–rata shares. This brings the total raised to $160m. The company was in no immediate need of new funding; rather, it just wanted to boost reserves at a time when shareholder sentiment was particularly high following news that a profit was earned in August.

Highly experienced management team

The company succeeded in raising so much initial capital, in the first place, because of the unique credentials of its creator, David Neeleman. Most of JetBlue’s current investors were involved in Morris Air, which Neeleman co–founded in 1984 and sold to Southwest in 1993. After a brief spell at Southwest, he helped start Canadian carrier WestJet, which went public in July 1999.

Neeleman began putting together a plan for New Air, as JetBlue was initially known, while waiting for his five–year non–compete deal with Southwest to expire. This, he said recently, gave him time to "really think it out". Some of the concepts were evidently tested at WestJet, the Canadian Southwest clone (see Aviation Strategy, March 2000). The end result was a solid plan which, in combination with Neeleman’s track record of starting low–fare carriers and making them successful, enabled him to raise the JetBlue funding "in a very short period".

If JetBlue becomes a huge success, Neeleman will inevitably be compared to the most admired US airline industry icon, Herb Kelleher. The two men’s leadership styles are very different. While Kelleher, a boisterous and fun–loving man, has built a personality cult to maintain the special "Southwest spirit", Neeleman, a devout Mormon, has gathered a strong management team to help him implement similar strategies.

The team includes industry veterans from Southwest and Continental. President/COO Dave Barger previously ran Continental’s Newark hub. CFO John Owen spent 14 years at Southwest as treasurer and in operations and planning. VP Human Resources Ann Rhoades headed the famous "People Department" at Southwest and is therefore uniquely qualified to implement a similar corporate culture at JetBlue.

New Airbus fleet

This year’s hike in fuel prices has really driven home the benefits of operating brand new aircraft right from the start. JetBlue never even considered doing it any other way. The A320 fleet also enables it to keep maintenance costs down, maximise efficiency, maintain good operational performance, offer high service quality and create the right image.

The aircraft is ideally suited to JetBlue’s requirements because it has more seats than the 737 models and offers the flexibility to serve markets that range from 280–mile intra–state to 2,400–mile coast–to–coast sectors.

Passenger comfort was a key consideration — the A320 has a wider cabin and can accommodate special perks like "roomy all–leather seating", and latest technology features like 24–channel satellite TV in every seat.

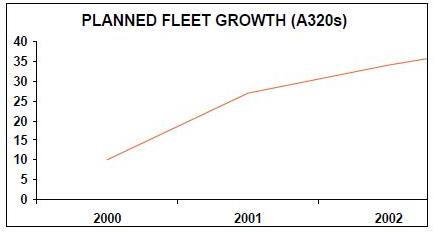

The initial April 1999 Airbus deal included 25 firm orders, 25 options and 25 purchase rights for the A320–232. In May this year seven of the options were exercised. Separate arrangements are in place to lease eight A320s from ILFC and SALE (five of which are already in the fleet). This adds up to 40 firm commitments, of which 10 will have been delivered by year–end. The remaining 30 are due in 2001–2003 (ten aircraft per year), and the options have delivery slots in 2003–2007. The contract includes some flexibility to convert to the smaller A319 and the larger A321 models.

Low fares, high service quality

JetBlue’s pricing is in the classic mode adopted by many low–fare new entrants. There are 21–day and 7–day advance purchase and walk–up fares, which represent typically 60–75% savings over what was previously available. There are no round trip purchase or Saturday night stay requirements. Fares from JFK to upstate cities range from $49 to $99, Florida is $79-$179 and California $99-$299.

However, JetBlue is more up–market than Southwest, as indicated by its assigned seating, leather seats and free latest–technology in–flight entertainment systems. In that respect it appears to have been more influenced by Virgin Atlantic.

Service philosophy, though, is very Southwest–style, with talk of "the JetBlue experience" and emphasis on open interaction with passengers and friendly but respectful service. Like Southwest, JetBlue goes to great lengths to select high quality employees, trains them well, does not cut corners as far as pay and benefits are concerned, and motivates workers with profit–sharing and stock options.

The airline has found an interesting solution to the problem faced by many new entrants, namely what to do when an aircraft breaks down. Since beginning two coast–to coast "red–eye" services in the summer, JetBlue has kept one of those aircraft at JFK during the day to serve as a back–up and to give flexibility for maintenance. It can apparently afford to do it because overall aircraft utilisation is already high.

This combination of offering low fares without sacrificing any aspect of service and with extremely high reliability thrown in has obviously made JetBlue a real hit in the marketplace. It achieved a 71.6% average load factor in the initial six–plus months through August 31, despite building operations from scratch, and has attracted substantial volumes of return customers.

Unprecedented efficiency

But how can it pull it off financially? Extremely low unit costs are the key, and the carrier aims to achieve those through "unprecedented efficiency". The ultimate cost target is six cents per ASM, which would make JetBlue the lowest–cost operator in the US.

In a presentation at a Merrill Lynch conference in June, David Neeleman released some interesting detail about the two specific things on the cost front that set JetBlue apart from the crowd — labour efficiency and aircraft efficiency. Incidentally, those are the factors that essentially account for Southwest’s success.

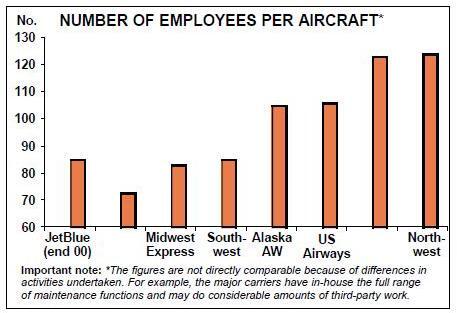

Neeleman predicted that by the end of this year JetBlue will have fewer employees per aircraft than any other airline. The year end target is 85, which is roughly what Southwest is currently achieving, and JetBlue is hoping for 70–75 by the end of its second year of operation.

Like Southwest, JetBlue benefits from a uniform fleet and high aircraft and gate utilisation. Initially its maintenance costs are lower than Southwest’s thanks to a newer fleet. Like Southwest, it offers competitive wages and employee profit–sharing. Its pilots are fully utilised and fly based on an incentive programme. Uniquely, all of its reservations agents are home–based workers, who are paid a relatively low hourly rate but can boost their earnings through an incentive programme.

Labour efficiency is also boosted by extensive use of new technology. JetBlue is, naturally, ticket–less and puts a heavy emphasis on the Web. In June Internet bookings already represented 40% of total bookings. The carrier said that it had booked so much business on the Web that it had 65 fewer people on its payroll than had been expected at that point.

To make absolutely sure that everyone understands that "low costs and efficiency are key to our survival", Neeleman said that he gives every single new employee an "airline economics 101 lecture".

Neeleman claimed that JetBlue generates more ASMs per aircraft on a year–round basis than any other narrowbody operator in the world, achieving levels similar to those of European charters in the summer. This is the result of operating larger aircraft (the A320s have 162 seats — 26 more than the 737–700 for the same fuel burn) and achieving high aircraft utilisation. In the early summer JetBlue’s A320s were already averaging 12 hours a day, and that was before night flights began to the West Coast. Aircraft are turned around in just 30 minutes.

The airline decided to serve two secondary coast–to–coast markets, JFK to Los Angeles (Ontario) and San Francisco (Oakland), mainly because they offered an opportunity to utilise aircraft at night. The incremental cost of operating those services was estimated at just 2 cents per seat–mile or about $50 per seat each way, so the services must be profitable with $99- $249 fares.

Growth plans and prospects

After the initial services linking JFK with Fort Lauderdale, Buffalo and Tampa with leased aircraft in February and March, there was a three–month gap until the A320 deliveries from Airbus commenced in June. But since late June JetBlue has added one or two new routes each month to include more Florida and upstate New York cities and the two in California. There has also been a Southwest–style rapid build–up of frequencies in the key Florida and upstate markets, many of which now have four or five daily flights.

The latest new additions have been Burlington (Vermont) and West Palm Beach (Florida), in September and October respectively. Fort Myers (Florida) and Salt Lake City (Utah) — where Neeleman grew up and launched his aviation career with Morris Air — are due to follow in mid–November.

In the short term, JetBlue will mainly focus on building up its Florida and upstate services — it has made a commitment to serve Syracuse next year and Portland (Maine) also looks likely. After that there are "tons of options" in the Mid–Atlantic region (the Carolinas), the Midwest and elsewhere.

In contrast to Southwest, which keeps its expansion plans secret as long as possible for competitive reasons, JetBlue has been publicising a list of over 40 cities it is considering serving from JFK within three years almost since its certificate application — evidently to ensure political support. The list includes both major and secondary cities in the eastern two–thirds of the country.

As for facilities, there are no foreseeable growth constraints at JFK. The 75 slots secured initially will be phased in over three years, taking JetBlue to the 32–aircraft mark. In 2004 it will be able to move to new and larger facilities at the airport. However, finding enough high–quality employees in the JFK area may turn out to be a challenge in the future.

JetBlue has drawn a predictably robust competitive response from the major carriers in terms of fare–matching. Pressures will continue as MetroJet is now substantially expanding its service to Florida and Southwest has just entered the Buffalo market. However, none of that is direct competition, and Southwest’s service from Islip on Long Island is not much of a threat to a JFKbased carrier.

As regards the larger majors, operating extensive domestic service from LaGuardia, JetBlue has a competitive product and can generate new traffic. If it can consolidate profitability, it is likely to go public within the next few years.