SIA's global ambition and the Virgin relationship

November 2000

SIA is surging ahead, producing another very good set of results, placing a mega–order for A3XXs and achieving an early return on its investment in Virgin Atlantic. SIA’s ambitions extend beyond being Asia leading carrier to becoming a genuinely global airline, and it looks as if it will achieve this status (although the tragedy of SIA’s first crash, of a 747 at Taipei, puts commercial success into perspective).

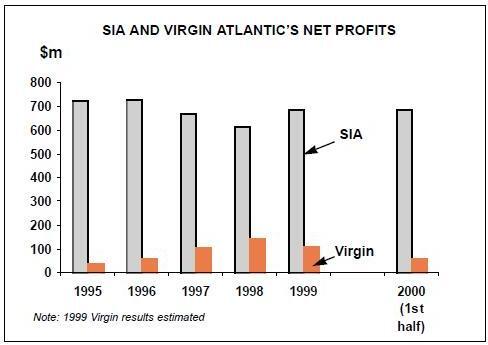

Pre–tax profits for the six months to the end of September totalled S$1.2bn (US$686m), an increase of 88% over the same period last year. Interestingly, this figure including a pre–tax contribution from its ownership of 49% of Virgin Atlantic of S$100m (US$57m). According to Kevin O'Connor of Deutsche Bank in Hong Kong, it was uncertain whether any contribution from Virgin would appear in these results. Assuming that Virgin Atlantic contributes a further S$25m in the second half of the year, SIA’s return on the reported S$1.6bn purchase price (including S$132m that was used as a capital injection), would be about 8.3%, slightly below SIA’s own estimate of its WACC of 8.5%.

Such is the strength of SIA’s balance sheet that the Virgin purchase and that of 35% of Air New Zealand still left it with net cash of S$1.8bn at the end of September. analysts are concerned that the company should be "working the balance sheet harder", which presumably means making more investments.

However, SIA’s criteria for making airline investments are fairly rigorous: it looks for a reasonable degree of management control and for genuine, as opposed to imagined, synergies. In this regard, the Virgin investment gives it access to the Atlantic market, although the two airlines do not code–share as yet and SIA is still pushing for fifth freedom rights from the UK.

One of the lessons of the Asian crisis for SIA was the desirability of having a presence in all the major long haul markets — Europe–Asia, Intra- Asia, Pacific and North Atlantic — in order to mitigate the effects of a severe regional downturn. The aim is to be able to move capacity smoothly between regions, so as to match differing supply and demand trends.

SIA’s A3XX order was 25 units, 10 firm plus15 options, to be deployed on routes to London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Sydney, Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, with an intermediate point on the US routes. They will complement the non–stop service SIA plans to operate to the US using A340–500s.

In order to realise the potential of its A3XX and A340–500 commitments, SIA will presumably want to place some of this equipment on key North Atlantic routes, like London–New York. This could simply be done through a cross–leasing agreement with Virgin Atlantic as part of a close cooperation strategy between the two airlines.

The problems are: first, although the two airlines have both have high quality in–flight products, they are different; second, despite its theoretical attraction, equipment sharing has never been effectively developed within an alliance; third, Sir Richard Branson’s relationships with business partners in the past have not been all that harmonious.

A speculative view

The alternative, and at present speculative, view of how the SIA/Virgin Atlantic relationship could develop is that SIA at some point will gain control of the other 51% of Virgin Atlantic. This would have to be done in cooperation with UKbased investors in order to protect traffic rights. These investors would have to be independent but in harmony with SIA’s strategy. Possibly British Midland could be brought in if Sir Michael Bishop decides to sell off the 60% of the airline still owned by him and his partners. (Virgin has approached British Midland several times with take–over proposals but was always repulsed.)

The outcome would be for SIA to have a genuine hub at London Heathrow in the same way as BA, for example, operates hubs at Changi and Bangkok. This evolution would also have the effect of underlining SIA’s equal importance in the Star alliance alongside Lufthansa and United. It could also remove some of the friction within Star arising from Virgin’s efforts in blocking British Midland’s transatlantic plans.

Virginal mystery

But what would induce Branson to sell his majority stake in his airline, the jewel in the crown of the Virgin empire?

The answer may lie outside the airline industry. The Virgin Group is a mysterious body consisting of 140 or so offshore companies and family trusts, which reveal very little financial information. What does seem to be clear, however, is that most of the Virgin brands — V2 (records), Virgin Cola, Virgin Direct (financial services), Victory Corp (clothes), etc. are loss–making. Those parts of Virgin that are open to stock–market scrutiny — like Virgin Express, the European low cost carrier — have revealed substantial losses and indebtedness. New ventures like Virgin Trains and Virgin Blue (the Australian low–cost carrier) have heavy capital investment programmes.

According to an analysis by The Economist published early last year, Virgin Atlantic had been acting as a cash cow for the other Virgin operations. But this role must have diminished because of harsher market conditions on the Atlantic in 1999. And now, with SIA owning 49% of the carrier, half of Virgin Atlantic’s pre–tax profits accrue automatically to Singapore, and the SIA directors on Virgin Atlantic’s board have an important say on major strategic issues such as capital expenditure.

Despite press reports of hidden cash mountains of £1 billion plus, Virgin has suffered a number of cashflow crises in the past. In fact, at least half the proceeds from the SIA sale went immediately to creditors and bankers of OurPrice, a chain of record shops owned by Virgin. Virgin Music, the original core company, and half of Virgin Atlantic have been sold in the past in solve such problems; the other half of Virgin Atlantic is the most marketable part of the Virgin empire should another cash crisis emerge.