US new entrants are bouncing back

November 1999

The US low–cost new entrant airline sector has bounced back strongly this year, after two years of heavy losses and turmoil following the ValuJet crash in May 1996. Many of the surviving carriers are now reporting healthy profits, while several new entrants have begun operations or are gearing up for launch with strong financial backing. Is the recovery sustainable? Frontier and AirTran, which are the largest survivors of the 1993–1995 crop of new entrants, are both now performing extremely well.

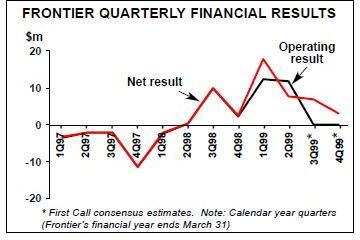

Frontier reported its first–ever annual net profit, $25.1m or 11.4% of revenues, for the year ended March 31, after losing $17.7m in the previous year. After paying a major loan back early, the carrier is virtually debt–free and had $70.5m cash reserves at the end of June, compared to just $3.6m in March 1998. Its rapid growth and new stability enabled it to move its listing from Nasdaq’s SmallCap to the National Market in the summer.

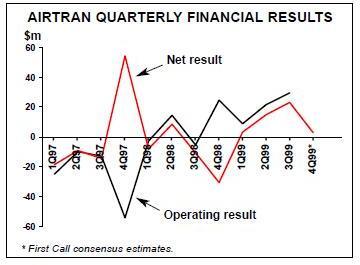

AirTran, in turn, has now had three consecutive profitable quarters — an indication that it has finally shaken off the negative ValuJet legacy and reinvented itself. It recently settled out of court its lawsuit against SabreTech regarding the ValuJet crash. Its cash reserves were a comfortable $55.2m at the end of September. After losing a total of $179m in 1996–1998, the carrier looks likely to post a net profit before special items of around $25m for 1999.

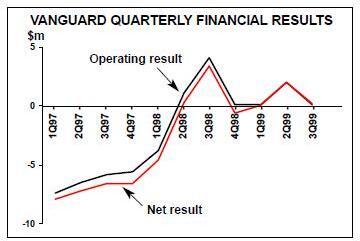

The brightened prospects are also reflected in the carriers' fleet plans. AirTran recently took delivery of the first of 50 717- 200s, for which it is the launch customer, and is now considering accelerating the retirement of its DC–9–30 fleet. In mid–October Frontier, in a notable departure from its previous strategy of leasing or buying used 737s, signed an LoI to purchase 11 new A318s and A319s. Even Vanguard, which was earlier viewed as an unlikely survivor, seems to have found a more viable niche after constantly switching markets.

After losing $25.8m in 1996 and $28.2m in 1997, the Kansas City–based carrier reported only a marginal $1.5m net loss for 1998. It has now posted small operating profits for six consecutive quarters. In the early summer the company successfully completed a reverse stock split and regained its Nasdaq SmallCap listing, though liquidity remains a concern. Vanguard must consider itself very lucky as the post–ValuJet era has seen the demise of many far more promising operators. The biggest disappointment was the failure of Western Pacific, which filed for Chapter 11 in October 1997 and ceased operations in early 1998. The carrier had developed a unique low fare niche at Colorado Springs but had expanded extremely rapidly, which meant that it had little cash left when it plunged into heavy losses in late 1996 due to the ValuJet effect. A year or so of continuous cash crisis culminated in a key investor backing out at a critical moment.

Of course, the failures included many struggling carriers that had little hope of long term survival in the first place, because they had chosen wrong markets or inappropriate business strategies. TriStar ceased operations in January 1997 and Air South in August of that year. The latter had little chance of ever making a profit, because it had no local traffic, and its majority–owner Hambrecht & Quist refused to inject more funds.

Pan Am went into Chapter 11 and ceased flying in February 1998 after losing $80m since beginning operations in September 1996. This was in part due to the ValuJet factor but also because of mistakes made in the choice of fleet (A300s) and markets. A late 1997 merger with equally cash–strapped and heavily loss–making Carnival did not help, and the combine ran out of cash while trying to restructure and consolidate their operations. However, Pan Am continued to operate charters, emerged from Chapter 11 in June last year with the help of a new owner and has just resumed scheduled operations.

But Kiwi, which has less of a name to sell, is now in the process of having its few remaining assets liquidated after a turbulent seven year history that included three FAA- imposed groundings, two Chapter 11 filings and frequent top management changes. The Newarkbased carrier, which was always highly rated for its service quality, last resumed scheduled operations in January 1998 and began venturing back to its old East coast markets, but debt remained high, cash reserves poor and losses continued.

Its third grounding by the FAA in March was the last straw. Although it was constantly on the verge of securing new strategic investors, none were in sight when needed in August and Kiwi filed for Chapter 7.

Greensboro, North Carolina–based Eastwind, which operated two leased 737- 700s to Trenton (New Jersey) and Orlando, suspended indefinitely its scheduled flights in September. This followed layoffs, route cutbacks and management changes implemented in the summer. The carrier has been looking for a merger partner or a buyer prepared to pay at least $10m.

But perhaps the most poignant admission of defeat came from Reno, which late last year agreed to be acquired by AMR because its leadership was concerned about long–term survival prospects for independent low–fare carriers. Reno was one of the most successful of the early 1990s start–ups and remained profitable through much of the ValuJet–induced crisis, even though it had to continuously restructure. It has now been more or less fully integrated into American — a process that turned out to be rather painful because of problems with American’s pilots union.

Post-ValuJet new entrants

Weaker demand conditions, a tougher regulatory environment, difficulty in raising capital and a tighter supply of second–hand aircraft in late 1996 meant that new applications and start–up airline activity in the US virtually dried up for more than two years. There was only one new low–cost entrant (Pro Air) in 1997 and none in 1998.

Although Pro Air managed to raise start–up capital without too much difficulty, it had to wait 15–16 months for certification. However, all the indications are that it has performed extremely well in competition with Northwest in some business–oriented markets out of Detroit. The company recently completed a $30m private offering, is in the process of launching a regional feeder operation and has initiated the IPO process.

The next new low–cost entrant, AccessAir, did not begin operations until February this year. The Des Moines–based airline links Los Angeles and New York LaGuardia with direct 737 services via points in Iowa and the Midwest. It has ambitious plans to expand to key cities on both coasts.

This year’s second new entrant, National Airlines, began low–fare 757 services from its Las Vegas hub in May. Its nonstop network now includes Chicago, Los Angeles, New York JFK, San Francisco and Dallas Fort Worth, with Philadelphia due to follow in November.

Northwest’s recent labour and service quality problems led to a rather interesting strategy shift for Sun Country Airlines. The old–established privately held charter operator introduced low–fare scheduled service from Minneapolis/St. Paul in head–on competition with Northwest in June. The initial experience must have been encouraging as the scheduled operations are now being expanded to business and leisure destinations all around the nation. Sun Country is also establishing a more permanent presence at key airports by signing gate leases and operational agreements.

In early October Pan Am finally resumed scheduled passenger operations with reconfigured 727–200s, linking Portsmouth (New Hampshire) with Orlando. This followed its Chapter 11 reorganisation and acquisition for $28.5m by New England railroad operator Guildford Transport Industries in June 1998. Late last year the company’s headquarters were relocated from Fort Lauderdale to Portsmouth, where it benefits from a state–of the- art maintenance hangar, a reservations centre and its own passenger terminal.

The new owners spent some time evaluating whether or not to re–enter scheduled service. According to the airline’s new president Dave Fink, the new strategy is to "slowly add destinations based on market demand and the ability to locate underutilised airport facilities". Service to Chicago is due to begin in mid- November. The company must demonstrate fitness to operate more than eight aircraft and submit a progress report to the DoT after the first year of scheduled service.

The most exciting of the new carriers gearing up for start–up is JetBlue (Aviation Strategy, August 1999), which plans to bring low fares to New York JFK in January, with initial services to Buffalo and Fort Lauderdale. JetBlue hopes to serve 11 cities with 10 aircraft by the end of 2000 and 30 cities in the eastern half of the country within three years. Earlier this year it signed an agreement with Airbus to acquire up to 82 A319/A320s, including 25 firm orders, 50 options or purchase rights and eight leases.

The venture, which has obtained fitness clearance from the DoT but still needs FAAcertification, has received overwhelming local and national political support as it will be New York City’s first–ever homegrown low–fare airline, with fares up to 80% lower than what is currently available. The DoT recently granted it an exemption to the "high density rule" at JFK for all the 75 slots it had sought JetBlue’s intention is to offer Southwest- style one–class, high–frequency service in markets that are under–served or have high average per–mile fares. It hopes to generate new traffic and eventually achieve unit costs comparable to those of Southwest.

The venture is the brainchild of its CEO David Neeleman, who co–founded Morris Air (which was bought by Southwest in 1993) and founded successful Canadian start–up WestJet, which went public in July. But the most remarkable thing about JetBlue is that it has secured about $130m in initial funding from a group that includes George Soros and Chase Manhattan Bank, making it one of the bestfunded start–up carriers in history. Unlike many of its counterparts, it will have the resources to weather competitive responses from established carriers.

But few other hopefuls can match JetBlue’s credentials in the eyes of investors. Among them, Northern Airlines, which has been in the making since at least early 1996, withdrew its certificate application earlier this year as it could not raise the funds. Probably for the same reason, little has been heard about AirPortland’s plans this year.

But there are cases where sheer determination helps. After persistently fighting American and airport and city authorities in the courts for many years, campaigning in Washington DC and even building its own terminal, Legend Airlines now hopes to begin low cost nonstop scheduled service out of Dallas Love Field to major business destinations early next year. It recently signed an agreement with Sabre to provide reservations, inventory control systems and consulting services.

Demand recovery

The 1996 events, which were followed by an extended debate about maintenance practices and safety, dealt a severe blow to the former image of a "penny–pinching" small low cost operator. The US consumer still demanded low fares, but established carriers were preferred. And the choice was there because the major carriers took full advantage of the situation by pricing more aggressively at the back end of the aircraft or launching low–fare subsidiaries like Delta Express (October 1996).

However, a combination of the public having a short–term memory about safety matters and extensive change implemented by low–cost operators to transform themselves into more conventional–type carriers appears to brought back the passengers. As long as product quality and pricing are right, demand for low–cost service has been strong over the past year. This has enabled the airlines to finally benefit from the economic boom enjoyed by the majors.

Smarter strategies

While carriers like AirTran have taken this as an opportunity to improve load factors, Frontier and Vanguard have been able to grow rapidly without adverse impact on the bottom line. Frontier’s capacity surged by 50% in the June quarter (the latest period reported), but that was fully matched by traffic growth. The company is confidently predicting 20% annual growth over the next two years and has signed an agreement to almost double its gates at Denver early next year. Vanguard’s 21% ASM growth in January–September was more than matched by RPM growth, which enabled it to boost its load factor to 69.2%. The low–cost new entrant airline sector has been able to bounce back because it has been able to adapt to changed circumstances. The smarter strategies include adequate capitalisation, more disciplined route selection and expansion, reinvesting profits in new aircraft, emphasis on service quality, better cost controls and yield management and embracing new technology and the Internet.

Several of the new carriers have opted to use cheaper and less congested secondary or third–tier airports — a strategy used very effectively by Southwest to ensure quick turnarounds, keep costs down and avoid undue attention from the major carriers. For example, the new Pan Am has chosen to operate to Gary/Chicago Airport, which probably few even knew existed and which the authorities are renovating in the hope of diverting traffic from congested O'Hare.

Another common theme is the utilisation of brand new aircraft. While AirTran and Frontier are only now moving to new fleets, new entrants like Pro Air, AccessAir and JetBlue regarded it imperative right from the start. New aircraft will help the public’s perception of an unknown company’s quality and safety, and they are more reliable and cheaper to operate — another good reason to ensure adequate start–up funds.

No-frills business classes

The new–generation low–fare entrants value new technology and regard the Internet as a useful distribution tool. Most have Internet booking capabilities. A recent research report by Salomon Smith Barney considered that the material benefits anticipated from the Internet will help Southwest and other low–cost carriers at the expense of the cyclical majors. The trend of low–cost carriers focusing on the higher–yield passenger segment has intensified over the past three years. No- frills business classes offering bigger seats and more legroom, assigned seating and FFPs have almost become the norm for the latest new entrants.

Exceptions, of course, are the likes of JetBlue that hope to emulate Southwest, though JetBlue’s brand new aircraft, leather seats and 24–channel live satellite television broadcasts at every seat may also appeal to business travellers.

Pan Am Mark III has enhanced its Clipper Class premium–service with more spacious business–class type interiors, achieved by reducing the number of seats on the 727s from 173 to 149, and more individualised service via extra flight attendants.

Much of the new expansion has focused on business–oriented routes. For example, this year Frontier has boosted its service from Denver to New York, San Francisco and Seattle, while AirTran recently introduced Atlanta- Newark flights. Pro Air has expanded in key business markets like LaGuardia and Chicago from Detroit.

The carriers typically offer advance purchase fares that are competitive with those of the major carriers, while significantly reducing unrestricted, walk–up and first class fares (which they can afford to do since their overall unit costs are lower). Not surprisingly, the fares appeal to the increasingly cost–conscious business travel segment.

One particularly popular strategy has been to go all out to secure corporate travel contracts, which provide a guaranteed revenue stream. Pro Air led the way with its multi- million dollar 10–year contracts with Chrysler and General Motors in the summer of 1998. The deals allow unlimited travel for a fixed monthly fee, saving those two companies $3m and $6m per year respectively. Pro Air said at that time that it hoped to build that base up to totally cover its costs, and it has since then secured many more similar contracts with smaller companies. The strategy has also been extensively used by Frontier, which signed its 2,200th corporate contract in the summer.

All of that has had an extremely beneficial impact on unit revenues and yields. AirTran’s revenue per ASM surged by 16% in January- September, which suggests that it has captured some higher–yield traffic from Delta. The introduction of the 717 will offer new opportunities to enhance service quality.

Frontier’s unit revenues surged by 21–28% in each of the past four quarters, though some of the improvement was due to more rational pricing in the Denver markets following WestPac’s disappearance.

Vanguard’s unit revenues rose by a remarkable 59% in 1998, from 6.28 cents to 10 cents per ASM, and another 12% in the first half of this year — a reflection of its presence in more high–yield markets. But a 38% capacity surge led to declines in yield and unit revenues in the latest quarter.

Will costs remain under control?

One of the biggest concerns are rising cost levels, which have been an inevitable consequence of the focus on business traffic and service quality generally. Vanguard’s and AirTran’s unit costs, at 9.80 and 8.40 cents respectively in the first nine months of this year, look much higher than what many feel low- fare carriers should achieve.

Frontier cut its unit costs substantially last year, thanks to improved aircraft utilisation, lower insurance costs, in–sourcing of ground handling and increased efficiencies through the growth of Denver hub operations. But its unit costs again rose in the June quarter, and another hike was likely in the latest period due to higher maintenance and flight operations costs and a late delivery of a replacement aircraft. However, AirTran managed to marginally reduce its unit costs despite service interruptions due to engine problems.

Competition rules

All the carriers faced a more challenging operating environment in the September quarter because of higher fuel prices and the impact of Hurricane Floyd. Both Frontier and AirTran warned in September that their earnings would be below expectations. There are some concerns about how the airlines will cope with growth, their fleet replacement strategies and labour cost pressures. Carriers like Frontier and Pro Air face newly–unionised worker groups. Frontier began paying bonuses to its employees earlier this year — a practice that it will probably have to maintain. While the DoT has yet to produce its long–awaited rules to prevent predatory behaviour, the mere threat of new rules and serious investigations, plus the DoJ’s antitrust lawsuit against American, appear to have made major carriers generally less aggressive in their pricing over the past 18 months. This has helped facilitate the recovery of the low–fare new entrant airline sector.

However, the continued specific allegations about predatory behaviour (most recently by Sun Country about Northwest) and complaints about being denied gates and other facilities at major airports suggest that the situation could quickly worsen, particularly now that the major carriers suffer from overcapacity in the domestic market. The DoT rules are still needed to give small low–fare carriers a chance to consolidate recovery.