Why should banks want to own operating lease companies?

November 1998

The purchase by Deutsche Bank of the medium–size US leasing company, Boullioun Services, from Sumitomo Trust, could signal an important trend in aviation finance.

Deutsche Bank will pay about $120m for Boullioun, which has a fleet of 38 737s, an orderbook of a further 60 (30 firm plus 30 options) plus a 36% stake in SALE, a joint venture with SIA. Other European banks with significant aircraft portfolios are looking to complete similar deals, either by buying up other small and medium–sized lessors or the leasing arms of other financial institutions. Some Japanese banks are being forced to unload their leasing operations as part of their overall restructuring efforts — for example, Sanwa is seeking approximately $900m for Business Credit Corporation, its US leasing subsidiary.

It is interesting to note that the residual GPA has been partly bought out from GECAS, with the US venture capitalist Texas Pacific paying about $115m for a 48% stake. GPA will be renamed AerFi Group and have a portfolio of about 80 A320s and 737s (at its peak in the early 1990s GPA’s fleet comprised 220 units with a further 400 on order). Texas Pacific’s main partner is David Bonderman, whose shrewd investments in Continental and Ryanair have proved so profitable in the recent past; he evidently now perceives latent value in operating lessors.

How profitable is aircraft financing?

Straight aircraft financing has not been a very profitable business for banks. Risks are minimised through government guarantees and ECA financing, and consequently banks have been achieving very low margins — for instance, 20 to 40 basis points (bips) above Libor on transactions with first–rank or flag carrier airlines. Even with higher risk airlines the margins seldom exceed 80 bips, such is the competition among banks for airline business. Although many banks have greatly downsized their aircraft financing arms, there is a reluctance to pull out completely, partly because bankers like to display model aircraft on their desks, more seriously because they want to maintain relationships with high–profile clients in the hope of participating in more lucrative financing business (mergers, acquisitions, rights issues, etc).

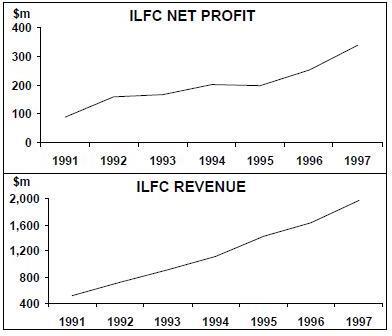

By contrast, the most successful of the operating lessors appears to be a paragon of profit. ILFC’s net profit margin was 17.3% in 1997 but it has also been able to maintain consistent profits throughout the economic cycle — its lowest net profit margin during the 1990s was 13.8% in 1995.

ILFC’s continuing success is closely associated with its ownership. In 1991 ILFC’s manager–owners astutely sold their company to the giant financial entity American International Group (AIG), which has a AAA credit rating. As a result ILFC has been able to achieve the lowest possible cost of capital, and so maximise the difference between its interest charges on its owned aircraft and the rentals paid by its lessee airlines. The financial clout of the group also enables ILFC to place bulk aircraft orders and so obtain the lowest possible unit prices from the manufacturers.

Through buying into Boullioun, Deutsche Bank is evidently hoping to replicate part of the ILFC success formula by giving the lessor access to its AA+ credit rating (as well as German tax–based lease structures). The leasing company will bring its expertise in managing assets throughout the cycle — at the most basic level, buying equipment in the downturn, selling close to the peak.

But there is another key reason for entering the operating lease business, which is related to the changing nature of fleet planning. Traditionally, the main customers of the operating lessors have been second–tier airlines, start–up carriers, charter airlines and Developing World airlines, whose balance sheet weakness preclude them from buying outright or entering into finance leases. Now, however, operating leases are being used by the world’s leading airlines as an integral part of their fleet strategies.

In deregulated markets predicting traffic volumes becomes more and more problematic, increasing the risk of exposing airlines to overcapacity in a downturn. A key concept for fleet planners is a core fleet supplemented by a flexible fleet than can be expanded or contracted rapidly in response to market conditions; the role of lessors is to supply the flexible fleet.

As the table below shows, the leading lessors now have placed a substantial proportion of their portfolios with major airlines in North America and the US. To penetrate further into this segment an operating lessor has to be able to compete with the leading airlines’ own financial clout and their ability to negotiate discounts from the manufacturers.

A promising growth prospect for the lessors is — perhaps surprisingly — Asia, where the leading airlines have generally eschewed operating leases. Sale and leaseback of aircraft has already become the main method for raising desperately needed dollar funds.

Networks are being radically revised, and airlines are frantically downsizing or “rightsizing” their fleets to match capacity to the new level of demand. Lessors are seizing the opportunity of switching surplus aircraft from the East to the West where there are still shortages of some narrowbody types.

Questions of timing

While there is a strong commercial logic behind Deutsche Bank’s investment, there are doubts about how widely this strategy can be followed by others. It is evident that the aircraft market is now moving into surplus as economies slow, Asian capacity is shifted to the Atlantic and deliveries of aircraft ordered in 1996 and 1997 are starting to accelerate. Widebody values are down 30% from the beginning of 1998 and narrowbodies are starting to come under pressure.

The timing of further purchases would not appear to be optimal, but as always the deals will be done if the price is perceived to be right. In assessing the premium a bank might be willing to pay over the lessor’s net asset value, it should be asking these types of questions:

- What is the quality of the leasing company’s management? How wide and deep are their airline contacts? How quickly and effectively do they react to a lessee slipping into financial difficulties?

- Does the composition of the fleet match up with future demand requirements? Are maintenance conditions rigorously monitored? How much flexibility is there in the delivery pattern of new aircraft?

- What is the nature of the lessee airlines? What is the likely default rate? Or even, are there too many first–rate airlines with strong lease negotiating powers in the portfolio?

| Jets leased to | As % of | |

| North American | lessors’ | |

| or European Majors | total jet fleet | |

| ILFC | 112 | 30% |

| Boullioun | 9 | 29% |

| Ansett | 25 | 23% |

| GECAS/GPA | 103 | 20% |