Brand line thinking inside the tubes

November 1997

Brand line design and implementation is one of the few tools available to prevent the airline industry becoming another commodity- based business. Some radical thinking is needed is this area, insists Louis Gialloreto.

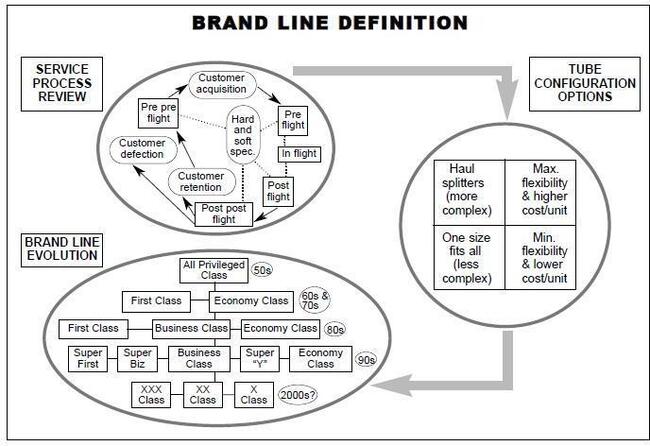

Airline services traditionally consists of three segments — pre–flight, in–flight and post–flight. But today there are two more segments — pre–pre, what drives a customer to one particular carrier rather than another; and post–post, what happens to a customer after leaving the airport and prior to returning for another flight.

For many airlines the pre–pre and post–post processes are divorced from the main sales and marketing effort. The acquisition and retention of passengers are seen as two different processes. In fact, airline managers simply fall into the trap of failing to look at service through the critical eyes of the customer, who sees these processes as a single continuum.

Bearing in mind this five–stage process we are focusing in this article on the evolution of the in–flight product, starting with some observations about the flying tube.

Stretching and shrinking are the watchwords of the 1990s and probably the 2000s; no major technological breakthroughs seem likely. Various iterations of the old 707 have now become a whole new family of 737s and 757s. No one is sure if the DC–9 tube will be around long enough to be an MD–90 variant of any significance. The A320 is being finely divided into 319 and 321 variants. The newly popular regional jet is succeeding in fitting 50 seats into a tube originally designed for 12.

As for widebodies, the 747 dominates with a double–decker version still an Airbus paper dream. We are losing the MD–11 (except for containers) and A330/340 tubes have replaced the comfortable L1011 tubes. The big new tube is the 777, which seems a modest replacement for the wider DC–10.

So what we have is various standard tubes with little new physical benefit for the passenger (although interior architecture attempts to widen the passenger’s perception of the aircraft’s dimensions). In fact, as tubes have been stretched to accommodate more passengers than the original design envisaged, we could well be regressing to the old DC–8–60/70 syndrome which minimised passenger appeal.

Tube stuffers

So what new things have we been putting in the tubes? How have we improved existing brands? What’s really attractive about the classes of service we offer?

Up to the early 1980s cabins consisted of first class and "not–ready–for first" class, at which point long haul fliers demanded a hybrid, called, appropriately enough, Business class. This was designed to placate those airway warriors who felt that the full fare Economy experience was ruined by having to sit beside a backpacker travelling on a bucket shop ticket.

In the 1980s — the years of conspicuous consumption — the offer of more for the same price was the right package for the Business Traveller. Thus we moved to a three–class configuration in most medium and long haul markets. Some carriers — like Swissair and Lufthansa — had a serious disregard for economics, proudly advertising three–class everywhere, anytime.

In the 1990s airlines have evolved two main approaches to designing airline service:

- Complex brand lines. On short and some medium hauls, airlines operate a two–class line consisting of combinations of Business, Super Business, Economy and Super Economy, while selling a traditional three–class product or new two–class variations on long hauls.

- Simplified brand lines. For airlines to whom standardisation means everything, either a one-, two- or three–class is made to fit throughout the carrier’s domestic and international network.

The complex approach is typified by British Airways, which has created a range of seven distinct products — Concorde, First, Club World, Club Europe, World Traveller, Euro Traveller and Super Shuttle. JAL and Swissair are also among the airline proponents of complex branding, with five lines each.

This enables the airline to segment in a way that fits in with corporate travel policies — different levels of executives are generally permitted to fly different classes depending on the length of haul.

The simplified approach, as adopted by airlines like Virgin Atlantic, Southwest and Canadian, aims to satisfy most of the passengers most of the time. By maintaining fleet configuration commonality, it should be a more cost–effective process.

Whichever basic approach is taken some key competitive questions have to addressed.

Super-First and Super- Business strategies

Virgin Atlantic’s innovative Upper Class concept has now been copied by other carriers (Continental, Canadian, etc). BA has responded by raising First class standards through the introduction of beds, a move followed by Air France and JAL.

In short, old First is being squeezed out by Super Business and Super First, leaving some carriers — which traditionally have promoted themselves as quality airlines — floundering. Swissair has proudly announced a 47" pitch in its long–haul Business class whereas the benchmark is now 52–55". It is trying to manage a three–class product with both the First and the Business class spec now being off benchmark. Similarly, KLM has undershot the standard in its own operations and in the KLM/Northwest version. And BA’s message about Superior seat ergonomics (the cradled Business baby) may not suppress passengers' suspicions about the actual seat pitch.

Given that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to be a player in both Super First and Super Business and have room left over for Economy, which strategy looks like the better bet?

Even in today’s buoyant market corporations are less willing to provide First class travel than they were in the 1980s boom, and in any case seasoned premium flyers are finding most of what they need in Super Business. It also seems that significantly more traditional First class travellers are retiring than those who are moving up to First for the first time.

A new development affecting the First class is the growing popularity of leasing corporate jets or buying into timeshare programmes. Suddenly many more First class passengers are able to make the economics of corporate jet operation work. American Airlines has seized on this trend through its affiliation with Jet Solutions, although at the risk of eroding its own premium travel base.

Nevertheless, BA, by being the innovator in the Super First class, has put itself in a strong position at present. BA launched its product at the beginning of the strong upturn in intercontinental travel, but airlines wanting to develop such a product now are likely to have much less time before the next downturn in which to make a return on their investment.

BA appears to be aiming to increase its share of First passengers in a market that is at best stable or more probably declining. BA may also have calculated that Super First would have the effect of pushing competitors out of this market altogether.

While this is an effective strategy in an upturn, it could cause problems in the next downturn, especially if those carriers which are being pushed out of the First Class market segment — the US Majors, Lufthansa, Qantas, KLM for example — succeed in redefining their Business product to Super spec and are able to compete much more effectively for that segment.

Other carriers which try to project a premium image — SIA, Cathay Pacific, Thai International, Emirates — are also going to have to revise their class strategy: they fly three classes but none them is now in the Super category. The choice is whether to upgrade First or Business, but, given the recent economic uncertainty afflicting the Asian markets, the Super Business option would seem more promising.

The need for Super-Y

While airlines agonise over their premium class strategies, they seem to be largely ignoring Economy class, which is very foolish. Most hard specs have remained unchanged over the past cycle or they have actually declined; US domestic passengers are now well advised to bring their own food, such is the quality or airline and airport fare. TWA’s experiment with "Comfort Class" was positive but failed to stimulate extra traffic, probably because of poor overall brand.

Again Virgin Atlantic emerges as a market leader with its Premium Economy class catering for the valuable and growing group of passengers in the hunt for a better class of value for money travel. In the next slump airlines that are able to offer this combination will be able to capture a disproportionate share of the "not ready for Business class" segment plus those passengers whose companies are no longer willing to pay Business class fares (with the development of Super Business the fare differential between Business and Economy is certain to widen).

Airlines are resisting developing a Super Economy product because it would require 33–34" pitches which would in turn knock out a couple of Economy class rows. This is a genuine concern for carriers that are trying to keep capacity tight, but in reality many airlines are now over–providing capacity which should allow some manipulation of seating. The next downturn will certainly give airlines the opportunity to experiment with new segments in emptier Economy classes.

One final point: airlines persist in defining their competitive advantage by describing hard specs — meals, seat pitches, IFE and so on. Customers, on the other hand, expect the best hard spec but tend to focus on the soft spec (human behaviour) as the key differentiator. Few carriers base their service line on soft spec but those that do — Southwest and Virgin again — are among the most successful.