Lufthansa: will it achieve star quality?

November 1997

On October 15 Lufthansa joined the elite club of fully privatised European flag carriers. Can it now challenge British Airways for the number one position?

Lufthansa’s share offer for the remaining 37.5% government share of the airline was twice oversubscribed, which was hardly surprising as the stock price of Dm33.3 was priced slightly down on the existing shares and individual investors were given a discount of Dm1 per share. More remarkable is that 37% of Lufthansa’s shares are held by non–Germans.

At the end of October Lufthansa was capitalised at Dm14.8bn ($8.3bn) compared with £6.2bn ($10bn) for British Airways. On 1997 price/earnings ratios Lufthansa is being rated by the stock–markets more highly than BA — at 21 against 14 — but this is largely reflective of more conservative accounting policies in Germany. On price/cashflow, Lufthansa is being rated at just under five while BA is achieving just above six.

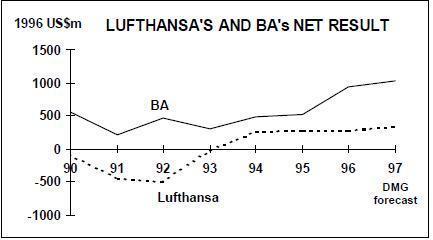

Lufthansa’s 1996 and first half 1997 results are shown in table below. Although Lufthansa’s revenue is now greater than BA’s, on key indicators it is still lagging: a cashflow margin of 9.5% against BA’s 12.6%, a net margin of 2.3% against 6.6%.

Still, Jürgen Weber, the CEO, describes Lufthansa as having undergone "a stunning metamorphosis". He is right: back in 1990/91 Lufthansa was the most unprofitable of the European flag carriers, worse than Air France, Alitalia and Iberia, and among the most traditional. Its slogan — "Growth through our own resources" — signalled its aversion to alliances.

When Weber was appointed CEO in September 1991, coming from maintenance arm Lufthansa Technik, the company faced disaster — a message he had to communicate to the management and workforce. In July 1992 Weber addressed 20 senior managers — known as the "Samurai of change" — at a crisis meeting which turned out to be the critical point in his presidency. Key issues were discussed for the first time, like conflicts between network management and the area profit centres, and the need to cut costs through, among other things, reducing the workforce by 6,000.

As all this was taking place in Germany the unions were closely involved. Accepting that no subsidies could be extracted from Bonn the unions, ÖTV and DAG, made concessions on redundancies and work flexibility, but insisted on monitoring the reforms. The Deputy Chairman of Lufthansa’s Supervisory Board is currently the ÖTV representative, Herbert Mai, but that does not necessarily ensure harmonious labour relations — the airline suffered short strikes last year.

The key elements of the turn–around were:

- The creation of separate business units, each with its own cost control and transparent profitability, which would have to "trade" with each other and with the core company. These are listed in the table left. The process is being carried to its logical conclusion as Lufthansa is considering the sale of its new integrated tourism operation, the result of a merger between Condor and NUR, Germany’s second largest tour operator; LSG Catering; and its 29% holding in the Amadeus CRS;

- The resolution of Lufthansa’s expensive inflexible pension scheme, the VBL, through a federal government subsidy of Dm500m plus Dm1.1bn of guarantees;

- The conversion of the existing Germany–US bilateral, which actually was very liberal in terms of capacity, frequencies and fifth freedoms, into a full "open skies" agreement, enabling the antitrust–immunised alliance with United to be signed in 1993.

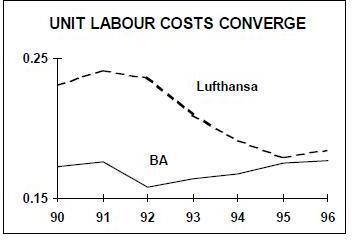

- Most fundamentally, implementation of the cost reduction and efficiency improvement scheme, known as "Programme 93". The results are clear from the graph below. Lufthansa’s unit labour costs in 1996 were more or less the same as BA’s, having been 30% higher in 1990; they have converged because Lufthansa’s physical productivity has increased enormously and because the inflation in average employment costs (each employee’s salary, social costs and pension) has been more moderate at Lufthansa

The private challenge

The question now is whether Lufthansa can continue this trend and adapt completely to the demands of being a 100% stock–market–quoted company. Before the announcement of the final privatisation, there were worries that the airline’s turnaround had been too rapid and too successful, and that managers were not yet mentally attuned to shareholder culture. The equity market has traditionally played a much smaller role in the German economy than in the US or the UK, but Lufthansa’s top 200 managers have been given a major incentive through a bonus scheme which is based on a comparison of Lufthansa’s stock relative to BA’s, KLM’s and Swissair’s.

The ongoing cost cutting regime is now referred to as "Programme 15" with the 15 curiously being an allusion to Dm1.5bn ($850m) of savings the airline plans to make by 2001. Although over half of these savings have already been identified, Lufthansa faces some difficult tasks as it continues to squeeze its cost base.

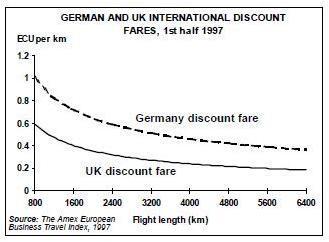

Moreover, Lufthansa is vulnerable because its profit equation depends on maintaining its yields. Its unit costs are now about 5% higher than BA’s and its average pax load factor is 4.6 points lower, but its average pax yield is 33% higher. The graph on the right illustrates the present difference in discount international fares, the choice of the value conscious business or leisure traveller, to/from the UK and to/from Germany: around 60% according to the latest American Express survey (although full business fares were much closer). German fares will remain higher for the foreseeable future simply because of the inescapable costs (airport charges, etc) of operating in the country, but it has to be assumed that the gap between the curves will narrow as deregulated competition increases.

Two vaguely related developments, mostly outside of Lufthansa’s control, will determine whether it can adjust to new fare pressure.

First, Germans are going through a painful reappraisal of their working habits — the so–called 9 months work for 13 months pay syndrome. Efficiency at work is no longer enough — much more flexibility in, for example, overtime worked to holidays taken is required especially in a service based industry. Lufthansa appears to be a leader among German industry in this regard, but it is still very difficult to envisage the unions agreeing to, for example, a new low cost European subsidiary, a plan they blocked in 1994.

Second, there is the prospect of EMU. In the first half of this year Lufthansa gained an estimated Dm125m ($90m) as a result of a 5% depreciation in the Deutschmark. Normally, however, it is used to losing money because of the strength of the currency. Weber is strongly in favour of the implementation of EMU by 1999, not just because of the stabilising effect on revenues and costs but also because EMU implies a harmonisation of national government’s social expenditure. Weber seems to suggest that Germany should be regarded as the norm — a compromise between France on the one side and the UK on the other. The UK government, however, has decided not to join EMU for four to five years. This could consolidate BA’s, and the UK–based low cost carriers', cost advantage.

Star alliance - the vision

On May 14th the Star alliance was unveiled — an exercise in branding existing agreements between Lufthansa, United, SAS, Thai, Air Canada and Varig (which joined on October 1st). Lufthansa’s strategic direction is dominated by this alliance.

Jürgen Weber describes airline alliances as the correct and natural response to changing demand patterns such as business and leisure passengers becoming more global in their thinking and choice. For example, Lufthansa’s key accounts may still be German–headquartered companies but they have shifted production to lower cost countries and concentrated their sales efforts in overseas growth markets, and the executives of these global corporations demand efficient connections to all these points as well as being assured of consistent quality service on their global travels. On the cargo side, a producer of micro–chips in Dresden is only one stage in a production process that encompasses Kuala Lumpur and Glasgow.

To meet this market demand, cross–border alliances were born, promising seamless travel and smooth connections with a trustworthy partner which is "the choice of the carrier of the passenger’s carrier choice". Weber waxes almost lyrical on the subject of alliances, which is unusual for such an effective and pragmatic executive; his vision of the future has echoes of Jan Carlzon’s 1980s tenet that the aviation world would reduce to five mega–carriers.

Weber proclaims: "Airline competition of the 21st century will be competition amongst airline alliances … Strong competition between strong alliances is a prerequisite to secure Europe’s position and to satisfy passengers and shippers".

The statement obviously alludes to the EC’s investigation of the competitive implications of the BA/American alliance as well as the existing antitrust–immunised alliances of Swissair/ Sabena/Delta and Lufthansa/United/SAS (that KLM/Northwest, the most comprehensive pool–sharing alliance, is not included in the investigation is illogical). The EC has committed to coming up with a report by the end of the year.

Lufthansa differentiates its alliance with United from BA’s with American on the grounds that it does not involve the consolidation of routes; it claims that of the 5,000 LH/UA code–shared weekly flights only two, Frankfurt–Chicago and Frankfurt–Washington, are duplicatory. Also, Lufthansa set the precedent for slot give–ups when it was asked to do so by the EC as a condition for the SAS agreement. Lufthansa probably needs the BA/AA alliance to go through in order to secure its ongoing relationship with United, but it is also needs to reduce the competitive threat of the alliance through slot and schedule concessions, exactly the same aim as the EC’s.

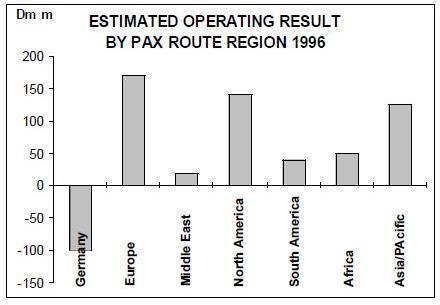

Lufthansa claims an operating benefit of Dm 240m ($135m) from its Star alliance in 1996, presumably mostly from United. As with all the alliances it is very difficult to assess the significance of this claim especially as Lufthansa does not officially reveal results by region. However, we would guess that it means that Lufthansa went from break–even to a profit of about $80m on the Atlantic last year at the same time as United improved its Atlantic operating profit by $76m to $86m. BA and American, as yet unallied, increased their Atlantic profitability by $79m to $587m and $53m to $180m respectively.

These numbers indicate the different scales of the LH/UA and the potential BA/AA groupings. To close the gap Lufthansa needs to take advantage of the time lead it enjoys over BA/AA and exploit to the full the benefits it is currently reaping: Atlantic passengers were up 21% in the first half of this year and, equally significantly, Lufthansa has been picking up high yielding frequent fliers who previously flew on BA when its FFP was linked with United’s.

Because regulatory approval for their alliance will not be given until January or February next year at the earliest, BA and American will not be able to provide a fully coordinated code–share service until the summer season of 1999 (as the IATA scheduling committee which coordinates slots and schedules for 1998 meets this November). This means that LH/UA will be five years old, and all of the operational problems should have been ironed out by the time that BA/AA finally takes off. BA may be considering the kamikaze option: refuse point blank to compromise on the number of Heathrow slots to be given up, accepting that this intransigence will scupper its own plans for American, but hoping that it will also force the EC to insist on the dismantling or downgrading of the other alliances.

Assuming the regulators leave it alone, can the Star alliance fulfil the potential Weber claims for it?

Alliances are inherently unstable entities. They break up because a member comes to believe that it is being exploited by the others; because a member decides that a rival partnership is more attractive; or because a member cannot accept a newcomer. Star attempts to minimise these risks through agreements which prevent code–sharing with competitors to the alliance and through promoting the full integration of FFPs (members earn miles on all of the partners' flights, not just the code–shared ones, plus Lufthansa uniquely pays German taxes on FFP benefits accruing to its high–earning "Miles & More" members). The six airlines have also established 20 working groups on cost saving, service standards, etc., which sounds like a potential bureaucratic nightmare.

Nevertheless, as Lufthansa’s sales prospectus points out, "the Star alliance has not yet been established on the basis of a firm and binding agreement … the parties have signed a non–binding Memorandum of Intent encompassing the guidelines of a contemplated agreement to be entered into in due time". The first test of the alliance’s internal bonding will come if or when an offer is made to Singapore Airlines plus Ansett, a move which has been widely speculated about but denied by Lufthansa. It would be very difficult to see Thai remaining in Star.

Then there is the question of the size of the alliance. Lufthansa wants to increase the global scope of Star by bringing in new members — SAA, British Midland, ANA perhaps. In the process Star risks turning into a Red Giant.

Lufthansa regularly monitors the service standards of its competitors — if they are found lacking there is a problem, if they are found to be superior, there is a bigger problem. This quality control must inevitably break down as the alliance expands and as other alliances, using their own global connections, offer services to the same points. The danger is that the lowest common service denominator will rule or that the alliance will become indistinguishable from the old IATA interline system.

This represents the downside but overall the globalisation strategy must be the correct choice for Lufthansa. It should minimise Lufthansa’s German cost disadvantage; broaden the geographical sources of profit (Lufthansa cannot hope to reach BA level of income on the Atlantic because the US–German market is so much more fragmented); and it fits in Lufthansa’s restrained fleet growth plans.

|

|

1996 |

1997 1H | 1997/96 1H chg |

| Turn Over | 20863 | 11524 | 10.6% |

| Opretaing Profit | 647 | 328 | 201.9% |

| Pre-tax Profit | 686 | 364 | 313.6% |

| Net Profit | 494 | 156 | 92.6% |

| Operating Cash Flow | 2070 | na | |

| Fixed Assets | 12509 | 12611 | -1.2% |

| Current Assets | 6182 | 7946 | 31.3% |

| Total Assets | 18691 | 20557 | 9.2% |

| Liabilities | 5671 | 6726 | 0.3% |

| Provisions | 7667 | 8500 | 17.1% |

| Shareholder's Funds | 5353 | 5331 | 10.0% |

| Liabilities & equity | 18,691 | 20,557 | 9.2% |

|

|

Revenue |

Operating Profit | Margin |

| Pax business | 13,623 | 436 | 3.2% |

| CityLine | 1,098 | 8 | 0.7% |

| Condor | 1,945 | 112 | 5.8% |

| Cargo | 3,431 | -53 | -1.5% |

| LH Technik | 2,866 | 68 | 2.4% |

| LSG (Catering) | 1,490 | 64 | 4.3% |

| LH Systems | 527 | 31 | 5.9% |

| TOTAL | 24,980 | 666 | 2.7% |