New economy, new aviation, new danger

November 1997

The "new economy" promises inflation–free sustained growth and an end to the business cycle. Airlines, with their predilection for forecasts of perpetual 6%-plus annual growth and inevitable market shares increases, risk being enticed by this new theory.

The idea of the new economy originated, inevitably, in the US as analysts struggled to explain how the economy was able to sustain such high growth rates and such low unemployment rates without inflationary pressures reappearing. The explanation was that a fundamental change had taken place in the way the economy worked because of the processes of globalisation and IT development.

Globalisation meant that costs were being contained through sourcing production from cheaper areas of the world while the market for goods and services had expanded enormously. The IT revolution meant that productivity had been boosted onto a new level. Both processes have helped erode trade union power and labour market rigidities.

The new economy idea (more pretentiously known as the new paradigm) has been accepted, at least in part, by economists at leading investment banks in the US, and has drifted across the Atlantic to the UK which is also currently experiencing strong growth without inflation (although interest rates have been increased on concerns over overheating).

Leaving aside the fanatics who claim that all limits to economic growth have now vanished, proponents of new economy do raise some intriguing points. In the new economy it is less likely that production bottlenecks will be encountered so sudden inventory changes, which are thought to cause turning points in the economic cycle, can be avoided. It may now be possible to have sustainable demand growth and diminishing unit costs at the same time.

How could the airline industry fit into the new economy?

Happy airlines

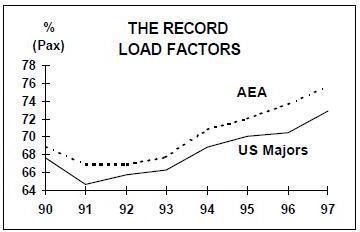

We are now in the sixth consecutive year of the upturn in the traffic cycle, significantly longer than the traditional four–five year phase, and there is little sign that the growth rate is slowing. The US Majors recorded 5.2% growth in the first eight months of the year; AEA international traffic shows a 10% increase for the same period. Load factors are at record levels — 75% for US carriers, 73% for European.

It would appear that, far from the demand for air travel becoming saturated, new markets are opening up as new strata of society move into the flying class and existing flyers fly more often. Nor is the traffic growth based on yield dilution; airlines have been able to push fares back up over the past 18 months.

On the capacity side of the equation it is possible to point out changes which, maybe, now allow airlines to take full advantage of buoyant demand conditions. The leading airlines could claim that they have learnt to control supply, or minimise the risk of overcapacity.

First, there is the mega–flexi–order as placed by American, Delta and Continental. In return for dedication to one manufacturer the airline gets the benefit of bulk buying plus control over when and in what numbers the aircraft are delivered, so avoiding the sad coincidence of peak deliveries and deep recession. The EC’s decision prohibiting Boeing from including sole–supplier conditions in its contracts is more or less irrelevant to the commercial reality as Delta’s recent statement on its $6bn Boeing order indicates — Delta recognised Boeing as the sole supplier but noted that Boeing would not enforce the exclusivity “unless permitted to do so by the EC”.

Second, there are alliances, which represent a way of expanding into new international markets without gearing up with new equipment. It is not necessary to take on the risk of additional capital investment in order to expand because the airlines that are able to form powerful alliances can, in effect, use the equipment of their partners. And if the alliance allows joint seat inventory control then load factors can be pushed up.

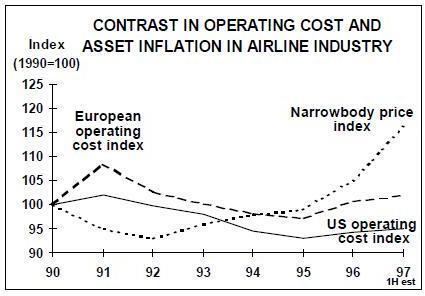

There is also the issue of cost restraint during the upturn. Leading airlines have not just been able to prevent operating costs escalating, they have managed to reduce them. According to our index of airline labour costs (see page 21), labour costs per ATK were 6% lower in 1996 than they were in 1990 for the leading US Majors and 12% lower for the leading European carriers. Overall unit operating costs dropped in the US but remained stable in Europe, the result of increasing efficiency outweighing increase in individual employee costs.

The IT revolution has impacted airlines as well. New CRS and E–ticketing programs hold out the promise of continuing falls in administration and distribution costs. Ever more sophisticated YMSs are also contributing to the record load factors and stable yields.

The warning signs

But does this really indicate a new aviation economy?

The evidence shows that the leading airlines have made important advances in developing successful strategies for a deregulated and increasingly globalised market, but the fundamentals have not changed. Specifically, an objective review of supply/ demand trends reveals market balance could be somewhat precarious (see following story). Even with continuing strong demand the aircraft surplus starts to bulge next year.

The worrying aspect is that speculation has returned to the aviation finance markets.

In the last recession asset inflation led to excessive borrowing and the precarious leveraging of airlines just before demand collapsed, partly as a side–effect of the Gulf war.

The warning signs of a new wave of asset inflation in the aviation industry are:

- Second–hand values are zooming skyward: for example, the value of a five–year old A320 is estimated to have increased 15- 20% over the past year.

- Lessors have re–entered the market in a big way: ILFC in September placed a $7bn order for A330s, A320s, 737s, 757s, 767s, 777s and 747s — not quite a return to the mega–orders of 1990 when GPA attempted to take over the world, but pretty significant nevertheless (some mini–GPAs have now appeared, like Pembroke Capital which placed a $500m order for 737s in March).

- Some banks are now offering 100%-plus financing on aircraft deals in anticipation of further increases in values; production slots are being viewed as scarce, tradeable commodities; low margins are available even for second- rate clients and new banks have entered the aviation finance business for the first time.

At the same time as debt again threatens to balloon, old fashioned cost pressures have re–emerged. Labour disputes at nearly all the major US and European airlines are being settled with substantial concessions from management. There is a grim determination on the analysis part of unions to recover some of the ground that has been lost over the past five or so years, even from union members who are also shareholders at United. Management’s strength in demanding trade–offs for pay increases or job security — for example, changes in working practices from BASSA at BA or the establishment of a low cost subsidiary at USAirways — is not as evident as it was even 12 months ago.

The new economy concept is being used, or rather misused, as an explanation and justification for very high stock–market valuations, which is dangerous. In the aviation sector the danger is that airlines and their financiers will again ignore the perils of the business cycle, allow debt to accumulate, operating costs to rise and capacity to explode. Operating cost inflation has been brought under control but asset inflation is threatening to get out of hand again.