Vueling: A new focus

on “Quality”

May 2018

Vueling has undergone a significant turnaround over the last 18 months — but is this due primarily to the LCC’s management or the imposition of new practices and discipline by IAG?

Based in Barcelona, Vueling was founded in 2004 before merging with Clickair in 2009 (see Aviation Strategy, May 2009). After being bought by IAG in April 2013, today the LCC operates to more than 100 destinations in Spain, Europe, North Africa and the Middle East out of 14 domestic bases (Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao, Oviedo, Valencia, Alicante, La Coruña, Palma de Mallorca, Ibiza, Seville, Malaga, Tenerife, Santiago and Las Palmas) and five international ones — Rome, Florence, Paris, Amsterdam and Zürich.

Vueling follows the standard LCC business model though with a focus on both leisure and business passengers, with an FFP called Vueling Club and three fare types, one of which — Excellence — is a basic business product that includes access to lounges, ticket flexibility and in-flight catering.

Vueling currently operates a fleet of 109 aircraft, with an average age of just over seven years. It comprises five A319s, 89 A320s and 15 A321s — all of which are Classic models rather than neos, though 47 A320neos are on firm order.

In calendar 2017 Vueling reported revenue of €2,085m — just 2.9% up on 2016, despite a 6.4% increase in passengers carried, to 29.6m. Average revenue per passenger dropped 3.3% in 2017, to €70.50, but unit revenue per ASK increased 1.5% year-on-year, to 6.07€¢.

However, operating profit rose from €48.4m in 2016 to €181.1m last year, and net profit increased from €48.9m in 2016 to €117.3m in 2017. This was largely due to a 3.4% reduction in costs in 2017, with fuel down 14.4% year-on-year thanks to “significantly better performance on hedging than in 2016”. Non-fuel costs rose by 0.3% in 2017, which was notably less than the increase in revenue. Unit cost per ASK (excluding fuel) for 2017 was 4.35€¢, some 1.1% up compared with 2016, but total unit cost last year was 5.61€¢ — 4.8% less than in 2016.

The results were part of a turnaround at the airline that Enrique Dupuy de Lôme Chávarri, CFO of IAG, calls “very efficient”. The CFO says Vueling “spread itself too thin during 2015 and 2016 as it went through growth then”, and Willie Walsh, CEO of IAG, also said “the quality of expansion in 2016 was not good”.

Strategy tweaks

The key to the turnaround has been an adjustment in Vueling’s strategy, with an emphasis — according to Dupuy — on improving the “quality of the network” — ie focussing on more frequencies to existing routes rather than adding new destinations.

Vueling launched only five new routes through the whole of 2017, and last year the airline’s capacity rose by just 1.5% year-on-year — though with traffic up 3.8%, the passenger load factor increased 1.9 percentage points to 84.7%.

Frequency growth has focused primarily on the Barcelona base, and it’s clear that Vueling’s prime objective is to consolidate and strengthen its position there. Last year Vueling had a 36% share of all passengers carried through Barcelona’s El Prat airport — well ahead of its closest challenger, Ryanair (with 14.7% — see chart). That’s a significant increase in the lead over second place it had back in 2011, when Vueling had a 22% share, ahead of the now departed Spanair with 13% (see Aviation Strategy, December 2011).

The grip of the low-cost model on Barcelona is clear — the top four airlines in 2017 in terms of passengers carried were LCCs, accounting for more than 61% of the total market.

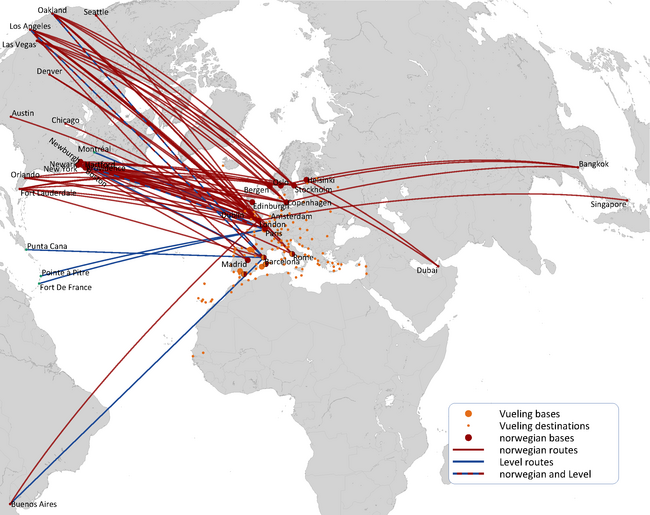

A new addition is LEVEL, a low-cost, long-haul airline that was announced by IAG in March 2017 and launched in Barcelona with two A330s (in a two-class configuration) just three months later. It currently operates from Barcelona to Oakland, Buenos Aires, Los Angeles (the summer only) and Boston (the latter launching in March this year). A third A330 will join the Barcelona-based fleet this summer, while a second base, at Paris Orly, will launch in July this year, with two A330s stationed there.

Walsh says feed from Vueling (and other IAG airlines) into LEVEL “hasn’t been as important with the start-up as we thought”, and that feed hasn’t been needed as LEVEL’s point-to-point demand on underserved city pairs has been strong — though “ultimately, we do believe that feed from short-haul makes the long-haul model work in the long-term”.

El Prat strength

Vueling is based at Terminal 1 at El Prat, a facility that was opened in 2009 and which brought Barcelona’s capacity up to 55m passengers a year (the previous Terminal 1 then became Terminal 2). But El Prat probably only has a few more years of passenger growth before it hits this maximum capacity, and so a new satellite terminal — called T1S — that will increase annual capacity by another 15m passengers, will be built by 2026.

This February the Spanish Ministry of Development announced total expenditure of over €2bn on a “Master Plan” to 2026 that includes the new terminal and investment in a new high speed (AVE) train connection between El Prat and Girona airport, effectively linking the two as a single airport system.

Girona airport is 92km north of Barcelona and carried just 1.9m passengers last year — though Ryanair accounted for 1.4m of them, which emphasises the Irish LCC’s position as the main rival to Vueling. Ryanair also operates out of another Catalan airport — Reus, to the south of Barcelona, which handled a total of 1m passengers in 2017 (of which Ryanair accounted for 370,000).

Both Vueling and Ryanair are benefiting from (and clearly contributing to) the increasing prominence of Barcelona airport compared with its main rival within Spain — Madrid Barajas.

As can be seen in the chart, in terms of passengers carried the gap between the two airports has shrunk slowly but steadily. Back in 2000, expressed as a percentage of passengers flown through Madrid, Barcelona carried 60% of the passengers that its great rival did, but this had risen to 89% by 2017. That’s due to a variety of reasons, not least because Barcelona’s economic and tourism importance has grown much faster relative to the capital in the last two decades, and (clearly related to that) because of a significant increase in point-to-point routes to/from Barcelona — pioneered by LCCs such as Vueling.

Domestic focus

As part of its turnaround strategy, at the same time as higher frequencies on existing routes Vueling has also been redistributing capacity from international to the domestic market, where it says “the company is more profitable, to the detriment of other markets with a lower return”.

Looking at the Spanish market as a whole, Vueling is in second place compared with Ryanair (see chart), with a 14% share (Ryanair has 17.7%). In relative terms, however, Vueling’s share has improved significantly since its takeover by IAG. In 2011 its share of the total Spanish market was 11.7% — much further behind Ryanair’s then 17.1% share. The Spanish market has grown substantially over that period (from 177.9m passengers carried in 2011 to 248.6m in 2017), but what’s clear is that Vueling’s share nationally depends largely on its grip on the Barcelona market, which accounted for 49.4% of all passengers carried to/from and within Spain by Vueling last year.

Vueling’s main Spanish competitor is Mallorca-based Air Europa, which dates to 1986 and is owned by Spanish travel company Globalia. Today it operates a mixed fleet of 45 aircraft on both short- and long-haul routes to Europe and the Americas. Out of Barcelona, Air Europa operates 15 competing routes, with 12 of them being to domestic destinations, and will increasingly become a rival as Vueling attempts to win further domestic market share.

Outside of Spain, Vueling’s operating bases at Paris and Rome (France and Italy are its secondary markets within Europe), are also seeing some frequency improvement, though Vueling has closed bases at Brussels, Palermo and Catania, each of which had a single A320 stationed there.

This tweak in strategy is a part of a major restructuring programme called NEXT, which Vueling has been implementing since late 2016.

NEXT has four objectives (or to use Vueling’s language, “pillars”) — to deliver an “LCC customer proposition”; to reduce costs; to develop a “high-performing organisation”; and to return to sustainable and profitable growth.

Some of that sounds like generic, meaningless MBA-speak; in plainer terms, what the company did was review all aspects of its operations. This ranges from technical changes (such as a new hand luggage policy and better turnaround times) to more automated processes to “better balancing depth and breadth” across its route network. A Phase 2 of NEXT is now under way, which is focussing on better management of seasonality in its resources, increasing its market share at destinations where it is already the market leader, and driving more digitisation within its entire business.

Whose idea?

Many of these NEXT efforts are being driven by what IAG is doing at a corporate level anyway. For example, through 2017 IAG has been taking measures to take a “digital approach to transforming” its business, with themes such as automation, data processing and digital innovation (which are all core parts of Vueling’s NEXT programme).

This leads to the bigger question of just how much of Vueling’s turnaround is due to its own management and how much is due to IAG mandates?

IAG beefed up Vueling’s management team through 2016, expanding its management committee from four to seven. Former Iberia CFO Javier Sánchez-Prieto became chairman and chief executive of Vueling in April 2016, replacing Alex Cruz (who became chairman and chief executive of BA), and in — in September of that year — the LCC hired Michael Delehant (formerly VP of corporate strategy at Southwest) as chief strategy officer (he is formally in charge of NEXT at Vueling).

Did the crucial about-turn in strategy to reduce expansion and focus on frequency on existing routes, plus a on emphasis on domestic rather than international markets, come from Vueling management, or was it driven by IAG? Unconfirmed sources suggest it’s more the latter than the former, and there certainly have been managerial “wobbles” at Vueling. For example, Sanchez-Prieto made bizarre (and erroneous) comments earlier this year that expansion of El Prat airport was being stopped by a no-fly zone over Leo Messi’s nearby house, which led to a boycott from some of the many fans of FC Barcelona in the city.

Ultimately, however, it’s not who initiated the strategic refocussing that counts, but that it is occurring and — for the moment — succeeding. There are signs, though, that capacity restraint is starting to ease off. In the first quarter of 2018, Vueling’s capacity rose 5.9% compared with January to March of 2017 (traffic rose 9.2% in the period, leading to a 2.3 point rise in load factor, to 74.8%). And capacity increases will accelerate during 2018 — in the second quarter of 2018 and FY18 capacity is planned to be +12.1% and +13.3% respectively.

Perhaps Vueling’s management is worried by some of the more adverse effects of the effective capacity freeze in 2017. Since 2012 Vueling’s employees have almost doubled but ASKs have always grown faster — until 2017 that is, where for the first time in recent years the airline’s capacity growth fell behind the increase in employees, leading to Vueling’s first drop in productivity (as measured by ASKs per employees) in its history.

There are other challenges, not least of which is Vueling’s image in the market. For example, Vueling is notorious among its regular customers for late departure times. Even using the usual 15-minute fudge that allows up to a quarter of an hour delay before departing flights are declared “unpunctual”, in 2016 the proportion of punctual flights was well under 70%. After a huge effort to improve this, the 2017 figure at Vueling improved by 11.3%, to 79.9% — but there is still a lot of improvement to be made before Vueling catches up with Iberia’s 2017 punctuality figure of 90%. (It must be added that this is a problem affecting all airlines operating to El Prat Barcelona airport.)

The map presents an image of a formidable low cost IAG network, merging Vueling’s southern European power base with Norwegian’s dominance in Scandinavia markets, and linking into Norwegian’s, and Level’s long-haul bases and Atlantic and Far East operations.

In practice, integrating the three airlines is likely to be problematic — different cultures, different fleets, the risk of undermining loyalty to regional brands, and so on. Then there might be broader strategic issues for IAG: can the markets, especially the Atlantic, be segmented into full service and low cost in the long term? To what extent will the new IAG integrated low cost airline compete with the network carriers in the IAG Group?

Part of the reason that Vueling has worked as an LCC within IAG is that it is in effect the flag-carrier of Catalonia. A Europe-wide and intercontinental LCC within IAG would be a different proposition. Indeed, there may still be a corporate memory at BA of what happened with Go; that low cost associate started to compete too effectively with BA on some key intra-Europe routes, with the UK competition authorities insisting on Chinese walls between BA and Go as it considered that Go could be used unfairly to block other low cost new entrants. In the end BA divested Go and it eventually ended up in easyJet.

Source: AENA