WestJet: Pioneering a new model in transatlantic flying

May 2016

WestJet, Canada’s JetBlue-style LCC, has embarked on a significant new phase of its international expansion: nonstop flights to London from six Canadian cities with its own 767-300ERs. How exactly does WestJet plan to make money in the competitive transatlantic market where it does not have much of a cost advantage?

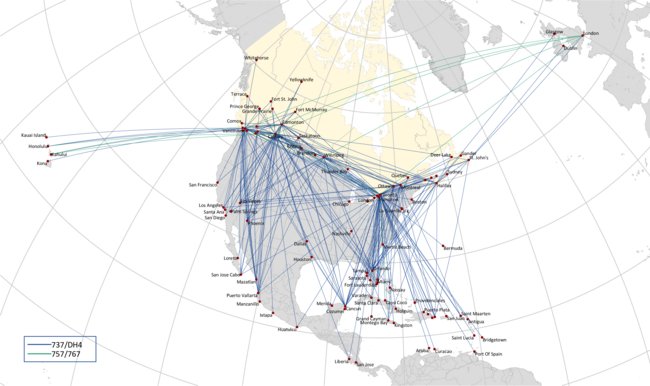

The Calgary-based carrier launched its first widebody transatlantic flights at the beginning of May and plans to operate as many as 56 weekly flights to and from London Gatwick this summer. Toronto and St. John’s have daily service, while Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary and Winnipeg have 1-6 flights a week. Calgary and Toronto will be operated year-round, the others seasonally. The St. John’s-London route uses 737NGs; the others are flown with 767-600ERs.

With introductory one-way fares as low as £177 (C$238) and C$20 add-on fares available to/from other points in Canada, there must be many happy people in Canada and the UK who will now be visiting their friends and relatives across the Atlantic this summer.

At Gatwick, WestJet’s passengers can connect to flights operated by codeshare partners BA and Emirates, as well as various LCCs’ services, so perhaps the new transatlantic services will also be a viable option for travel between Canada and continental Europe and further afield.

Transatlantic expansion is just the latest of many new strategies WestJet has adopted in the past three years. Most notably, the carrier has moved aggressively to capture business traffic in Canada, launched regional subsidiary WestJet Encore and entered the Canada-Hawaii market (initially with wetleased 757-200s).

The London move may seem aggressive, but in reality it is more like an evolutionary development for a carrier that is financially very successful and tends to grow its network cautiously and at a measured pace.

WestJet has been testing the transatlantic market since June 2014, when it launched its own daily scheduled seasonal Toronto-Dublin services with 737s, operated via St. John’s (Newfoundland), a stop mandated by ETOPS rules. Those flights were successful, so they were resumed in May 2015, when WestJet also launched its second transatlantic route, Toronto-Halifax-Glasgow.

Likewise, WestJet minimised risk by entering its first long-haul overwater market, Alberta-Hawaii, with wetleased 757-200s. The 767-300ERs now on the transatlantic were first tested on the Hawaii routes, beginning in January 2016.

The four 767-300ERs in the fleet are ex-Qantas aircraft acquired from Boeing in a July 2014 agreement (delivered between August 2015 and April 2016). WestJet is moving very slowly with further fleet plans, taking its time to acquire more used aircraft and pick the 767's longer-term replacement.

Despite its low-key approach, WestJet is probably a good candidate for network growth and diversification. It has an impeccable profit record, a strong balance sheet and ample cash reserves. It has consistently met its ROIC target. It enjoys a relatively low cost of capital, having in early 2014 become only the second airline in North America to be rated investment grade (after Southwest; Alaska became the third in June 2014 and Delta the fourth in February 2016).

WestJet has a unique people-focused culture, an award-winning product and a strong brand. It benefits from a non-union workforce (a rarity for North American airlines). It has high productivity and efficiency levels and great cost controls.

And WestJet needs new growth areas. It does not have the opportunities that US LCCs enjoy in being able to tap the huge US market for domestic and near-international expansion. It has already captured 40% of the Canadian domestic market and entered the key transborder business markets. It is already a major player in the Canadian winter sun market to Florida/Mexico/the Caribbean and has staked out a position in the Canada-Hawaii market.

Many of WestJet’s traditional markets have seen adverse macroeconomic trends over the past year or so. Canada’s GDP grew by only 1.2% in 2015 amid a slowdown in the energy sector. WestJet is heavily exposed to the economic weakness in Alberta and the Prairie provinces.

The Canadian dollar’s plunge against the US dollar has led to a sharp decline in southbound Canadian travel. While Canada is now a bargain for travellers from other countries, those coming from the US tend to fly on US airlines. In the Canada-Europe market, WestJet arguably has a better chance as a price discounter to capture Europe-originating leisure traffic.

While WestJet seems well positioned to make the transatlantic operations a success, the venture also poses many risks. First, it is a new area of overlap with Air Canada. Competitive clashes between the two have escalated significantly in the past three years. As WestJet set up a regional subsidiary, Air Canada added regional turboprop operations. As Air Canada launched its low-cost unit Rouge for international leisure markets (2013), WestJet began its seasonal transatlantic forays. As WestJet began tapping the business segment, Air Canada implemented successful cost cutting; the result of that has been a narrowing of the cost gap between the two airlines.

Second, on the transatlantic WestJet is exposed to competition from a multitude of airlines. It is the sole operator only on the Winnipeg-Gatwick route. In many of the other markets, it competes head-on with Air Transat, another Canadian low-cost operator.

Third, like other LCCs, WestJet has less of a cost advantage on long-haul routes. Much of its near-term cost advantage in the Gatwick markets arises from the low ownership costs associated with the used 767s. What will happen when the time comes to replace those aircraft?

Fourth, adding a third aircraft type and a new international region increases the complexity (and hence the cost) of operations. But the larger aircraft and longer stage lengths will obviously have beneficial impact on unit costs.

Fifth, even though WestJet believes that the transatlantic operations will be immediately accretive to earnings, the combination of higher costs and super-low fares is likely to mean lower profit margins on those routes. The likely impact is to keep WestJet’s system operating margins well below those of US carriers.

Sixth, the new risks, negative unit revenue effects and reduced operating margins will keep many investors and analysts unhappy. Some have questioned whether WestJet has got its capital deployment priorities right.

The new transatlantic model

WestJet’s transatlantic business model has two unusual components: deployment of used 767s and imposition of ancillary fees such as a $25 checked-in bag fee.

While bag fees are now charged by nearly all airlines within North America (Southwest may be the only holdout), they are not common on the Atlantic. WestJet makes the reasonable-sounding assumption that since it is entering the markets with significantly lower basic fares than incumbent operators such as Air Canada, travellers will happily pay a $25 bag fee. And, of course, there are plenty of exceptions; for example, the fee can be avoided if one books with a WestJet credit card or through WestJet Vacations.

WestJet will also collect additional revenues from its premium class. The 767s feature a “Plus” cabin with 24 premium seats and a main cabin with 238 regular seats. The premium cabin has seats in a 2-2-2 configuration (the middle seat is blocked on the 737s) and offers hot meals and other amenities. The Plus product also offers priority boarding and security screening and flight change flexibility.

When revamping the Plus product last year, the airline also launched “WestJet Connect”, a new in-flight entertainment system featuring wireless internet connectivity and 450-plus films/TV programmes. As of May 2, all four 767s and 44 737NGs had been equipped with the system.

While low fares (at least compared to Air Canada’s) will be the key to getting the traffic on the London routes, ancillary revenues could meaningfully improve the viability of those operations.

WestJet also expects to be operating at very high load factors, similar to those seen on the Dublin and Glasgow routes.

But WestJet also enjoys network, scale and other benefits that will help it on the transatlantic. The key factors include strong VFR demand in the Canada-UK market, feed from WestJet’s sizeable Canadian route network, cooperation with BA, potential connections with other LCCs at Gatwick, and WestJet’s exceptionally strong brand (more on these factors below).

WestJet executives said at the carrier’s quarterly earnings call on May 3 that they had seen a strong market response to the new transatlantic services, with advance bookings running ahead of expectations. Feed from the network was “as planned”, while Sterling’s strength against the Canadian dollar had helped boost UK-originating bookings. The executives said that they still expected the London routes to be accretive to earnings this year.

The Atlantic is a tough market for LCCs, but WestJet has a reasonable shot at making it a success for the following reasons (in no particular order of importance):

-

Strong historical and ethnic connections

WestJet executives described London as “the crown jewel of international travel to and from Canada”. There are strong historical and ethnic connections between the two countries and therefore significant VFR traffic and steady demand. US LCCs’ experience in the Caribbean/Latin America has shown that VFR traffic makes a huge difference to the viability of low-cost air services.

-

Scale and network benefits

In its 20 years of operations, WestJet has built enough scale and critical mass in North America to successfully venture into long-haul markets. With its traditional 737 operations and now also smaller-market penetration with Encore, it has a strong domestic network that will feed the transatlantic services. It promises “convenient connections from cities across Canada in both directions”. It is in a much stronger position than point-to-point competitors without networks.

There could even be some feed from the US. WestJet has seen a “nice flow” of US point of origin traffic on the Dublin and Glasgow services. But the flow could be less to London because there is a lot of nonstop service in the London-US market.

-

Dublin and Glasgow experience

WestJet has gained useful experience and learned much about the transatlantic market with the 737 operations to Dublin and Glasgow. It has proved that the markets can be significantly stimulated by low fares. It has seen extremely high load factors and “decent margins” on those routes.

-

BA, Emirates and other partnerships

Even though WestJet operates to Gatwick, where BA has a lesser presence, it could benefit significantly from feed from BA’s services and the FFP partnership.

Earlier this year WestJet added Emirates as its 15th codeshare partner and the first partner with whom it will exchange Middle East and South Asia subcontinent traffic via Gatwick.

More such deals could be on the cards, because “enhancing alliance partnerships” is one of WestJet’s key focus areas in 2016.

-

Strong brand

WestJet is a high-quality LCC in the JetBlue/Southwest mould and benefits from an exceptionally strong brand. Canadian Business magazine has ranked it in the top three among 25 leading Canadian brands for four consecutive years. It enjoys much customer loyalty.

Fleet considerations

WestJet has not yet indicated which long-haul destinations could follow London. A year ago, when launching Glasgow, it tantalisingly said that it would become a “truly global carrier in the years to come”.

Widebody fleet plans are also up in the air. WestJet has been in talks with Boeing and Airbus for quite some time on a next-generation widebody that could replace the 767s from 2019 or 2020. But the management has also said that they would consider good used aircraft, such as A330s or 777s, and leasing aircraft. And they continue to look for additional 767s for growth in the interim period.

The 767-300ER programme experienced delays in getting ETOPS certification, apparently largely because three different international governing bodies were involved (Australian, US and Canadian). As a result, WestJet had to delay the type’s deployment in the Hawaii market (began in January).

But the 767 has also had reliability issues, as a result of which WestJet has contracted one aircraft from its former wetlease provider Omni Air International as a “hot spare” for the transatlantic, as it did for the delayed start of the 767 Hawaii operation.

The ex-Qantas 767s are 22 years old. The first aircraft has now achieved the same reliability level as the 737 fleet, and WestJet said that it knows from talking with its codeshare partner Delta, which has the world’s largest 767 fleet, that the type operates very reliably (though it must be noted that Delta’s success with older aircraft is partly due to its maintenance expertise and capabilities).

But relying on old aircraft is nothing new at WestJet either. The management has described the 767s as a “low-cost way of getting that line of business going, not dissimilar from how WestJet started 20 years ago with 30-year-old 737-200s”.

Financial strength

WestJet has been profitable through its 20-year history, except for a small operating loss in 2004. It has had double-digit annual operating margins since 2012, and last year’s margin was a record 14.1%. It earned a pretax ROIC of 12.8% in the 12 months to March 31, which was within its long-term targeted range of 13-16%.

However, after being the most profitable airline in North America in the mid-to-late 2000s, in recent years WestJet has fallen significantly behind its US peers both in terms of operating margin and ROIC.

There are several reasons. First, both WestJet’s capacity and industry capacity in Canada have grown at a faster rate, leading to a weak domestic pricing environment. WestJet’s ASMs rose by 6.7% in 2014, 5.2% in 2015 and 7% in Q1 2016.

Second, Canada has been in an economic slump in the past 18 months or so, mainly because of the fall in oil prices (Canada is a net oil exporter). As a result, domestic fares in Canada are at their lowest in six years. In the latest quarter, WestJet’s RASM declined by 11%.

Third, in the past couple of years the Canadian dollar has weakened significantly against the US dollar, mirroring the fall in oil prices (though this year has seen a slight rebound in both). It has increased WestJet’s dollar-denominated costs, such as leasing, maintenance and interest expenses.

WestJet has taken remedial action, including schedule adjustments in the Alberta market, deferral of three 737 deliveries, return of some leased aircraft (for the first time in its history) and a slight reduction in this year’s planned ASM growth to 7-9% (of which about six points will be expansion with 767s).

In addition to the growth in widebody operations, longer-term strategies to help keep unit costs in check include the substantial 737 MAX orders (see fleet table) and potentially increasing seating density following the installation of new slimline seats on the 737s.

In addition to growing widebody operations, which has a negative impact on unit revenues, WestJet also continues to develop the regional Encore operation, which has the opposite effect of improving RASM. Encore now accounts for 5.5% of WestJet’s system ASMs and utilises 27 Q400s, with nine more scheduled for delivery in 2016-2017. The unit recently added its first transborder destination (Boston).

In the first quarter, WestJet’s network was nicely balanced, with domestic operations accounting for 41% and international (including transborder) 59% of system ASMs.

The consistent earnings have enabled WestJet to maintain a healthy balance sheet. Cash amounted to C$1.4bn in March, representing 35% of trailing 12-month revenues. Adjusted debt-to-equity ratio was 1.38. But continued fleet spending has meant negative free cash flow, which is not likely to change anytime soon.

In early May, WestJet secured investment grade corporate credit ratings (Baa2) from a second rating agency, Moody’s, which mentioned the carrier’s “low leverage, strong liquidity, good margins and a long record of operating success”. In March S&P confirmed the BBB- rating and stable outlook that it originally assigned in 2014. Those actions probably speak louder than words about WestJet’s prospects in new long haul markets. There are not many other investment grade rated airlines on the transatlantic.

| Fleet | Future deliveries | Fleet | |||||||

| 31 Mar 2016 | Q2-Q4 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019-20 | 2021-23 | 2024-27 | Total | 2027 | |

| 737-600 | 13 | 13 | |||||||

| 737-700† | 59 | 59 | |||||||

| 737-800 | 43 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 48 | ||||

| 737 MAX 7‡ | 6 | 4 | 15 | 25 | 25 | ||||

| 737 MAX 8‡ | 4 | 7 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 40 | 40 | ||

| 767-300ER | 3 | 1◊ | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Q400§ | 27 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 36 | ||||

| Maximum fleet↑ | 145 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 18 | 15 | 21 | 80 | 225 |

| Lease expiries | -3 | -6 | -9 | -12 | -14 | -44 | -44 | ||

| Minimum fleet↓ | 145 | 8 | 2 | -2 | 6 | 1 | 21 | 36 | 181 |

Notes: † One leased 737-700 was returned on April 1. ‡ There are options to purchase ten 737 MAX aircraft for 2020-2021 delivery. The MAX 7 and MAX 8 orders can be substituted for one another or for the MAX 9. ◊ The fourth 767-600ER was delivered on April 12. § There are options to purchase nine Q400s for 2017-2018 delivery. ↑ all leases renewed. ↓ all leases allowed to expire.

Source: WestJet

Source: Company Reports