The Gulf Carrier Row: Real Risk or Pantomime?

May 2015

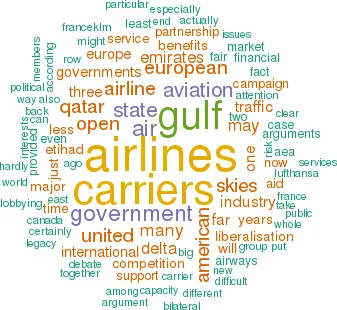

The attempt by the largest airlines in the US (and the world) to persuade the US government to create an “even playing field” with respect to competition from the Gulf carriers has attracted considerable attention, to put it mildly. The debate has quickly deteriorated into a virtual pantomime, ya-boo catcall politics made up of repeated claims and counter-claims but only limited actual illumination of the core arguments. It could be argued that in the real world none of it really matters much and might be expected to fizzle out eventually. In fact, it is far more serious than that. The row actually has significant implications and risks for the whole aviation industry which should be recognised and addressed.

The arguments

The arguments presented by American, Delta and United have been widely reported. They repeat the case made by other legacy airlines, especially in Europe and Canada, for some time. Essentially they maintain that Emirates, Etihad and Qatar Airways are in receipt of massive state aid from their respective government owners which distorts the market to such an extent that other carriers are unable to compete.

The lobbying group put together by the three US airlines — the Partnership for Open and Fair Skies — is clearly well resourced and has submitted a lengthy so-called White Paper to several US government departments.

The document is far from a rapidly put together case, a knee-jerk reaction to a recent problem. Forensic accountants and private investigators were initially hired by Delta some two years ago to examine the Gulf carriers' financial accounts and gather any other information which might appear incriminating. American and United joined later, together with unions representing the airlines' workforces.

According to their report, the accountants have discovered that the Gulf airlines have received some $42bn in aid since 2004, of which Etihad got $17bn and Qatar $16bn. The Wall Street Journal claims to have seen many of the original 44 documents, uncovered in almost 30 jurisdictions. Of particular note was the fact that, according to the research, at times international auditors only endorsed two of the Gulf airlines (presumably Etihad and Qatar) as viable businesses (or “going concerns”) on condition that further financial backing was provided by their shareholders. As the Partnership asserted: “State subsidies undermine free and fair competition, are in violation of Open Skies policy and threaten thousands of good American jobs.”

Or as The Economist commented, paraphrasing dialogue from the film Casablanca, the US airlines are shocked — shocked — that government aid is being provided to the aviation industry. But the initial document was not the end of the matter by any means.

The Partnership followed up with another report, this one produced by the economic consulting company Compass Lexecon, which concluded that the Gulf carriers are diverting passengers from US airlines rather than stimulating new demand. “The Gulf carriers assert that their service stimulates new traffic in key US markets, bringing substantial numbers of new passengers to the United States. We find little — if any — evidence that this claim is true... Instead, they are using their subsidized capacity to grow their networks at the expense of US and other carriers.”

The report goes on to warn that continued growth of Gulf carrier service to North America will prevent US airlines from serving more international routes, “which will harm passenger service to many small- and medium-sized communities”.

The Chief Executives of the three US airlines didn't hold back when introducing the second report, highlighting what they perceive as the dangers involved. According to American's Doug Parker: “It's a lot bigger than just international flying. It puts the entire hub and spoke system at risk”. United's Smisek noted that “we are under attack here from subsidized carriers who are basically taking our passengers — not through fair competition. When you're competing against arms of state and the treasury of oil-rich nations, that's a pretty tough row to hoe.” Hardly the most diplomatic of language. Of particular note is the reference to “our traffic”, surely a throw-back to the old protectionist days when sixth freedom operations were frowned upon.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the campaign has quickly attracted political support. In particular, at the end of April, 262 Members of Congress wrote to the Secretary of State and the Transportation Secretary supporting the US carriers' call for urgent consultations with the United Arab Emirates and Qatar about their “massive, market-distorting subsidies to their state-owned airlines... According to available research, each daily international round-trip frequency lost/foregone by US airlines because of subsidised Gulf carrier competition results in a net loss of over 800 US jobs.”

However, American, Delta and United have not had the field to themselves. Other US carriers have been quick to distance themselves from the Partnership's campaign, especially the all-freight consolidators FedEx and UPS. Consumer groups have similarly argued that any move towards increased protectionism and away from open skies is not likely to be in the interests of the travelling public.

Several airports and JetBlue Airways have also not been slow to express their concern, while although less public in expressing its views, Boeing cannot be pleased with developments — after all the Middle East airlines account for at least 10% of its business.

CAPA has criticised the Partnership's submission for being short of subsistence in identifying any serious harm to US airlines from the expansion of the Gulf carriers, an important prerequisite when it comes to proving predation. The US airlines are, after all, currently enjoying one of their most profitable periods, earning a net return of almost $9 billion last year, equivalent to 45% of the global airline industry's total profits.

CAPA also noted that in the whole Partnership document there is only one reference to consumers, and that is merely a token quote. It concluded that “in many ways the White Paper is a throwback to aviation policies of 30 years ago.” It is also relevant, argued CAPA, that on a distance adjusted basis, the post-Chapter 11 US full service airlines actually have lower costs on average than the Gulf carriers, raising the question as to why they are unable to compete.

A business travellers' lobby group even highlighted a study undertaken as long ago as 1999 by the Congressional Research Service which calculated that since 1918, the US Government had provided no less than $155bn in direct subsidies to build airports and air traffic control facilities.

The Gulf carriers may initially have been taken by surprise at the scale of the attack from American, Delta and United, but it did not take them long to respond.

In particular, Etihad financed a study by The Risk Advisory Group of the financial and other government benefits received by the three US airlines. The conclusion was that they had obtained aid amounting to over $71 billion in total, of which some $70 billion had been received since 2000. Most of these benefits came from bankruptcy restructuring under Chapter 11 ($35.5bn), followed by pension bailouts totalling $29bn.

Presenting the analysis, which he described as “conservative, quantifiable and credible”, Etihad's General Counsel Jim Callaghan said: “We do not question the legitimacy of benefits provided to US carriers by the US Government and the bankruptcy courts. We simply wish to highlight the fact that US carriers have been benefiting and continue to benefit from a highly favourable legal regime, such as bankruptcy protection and pension guarantees, exemptions from certain taxes, and various other benefits. These benefits, which are generally only available to US carriers, have created a highly distorted market in which carriers such as Etihad have to compete.” 15 All! cried the tennis umpire.

Emirates, Etihad and Qatar are all relatively young airlines which have grown at a remarkably fast rate. Their aircraft orders from both Airbus and Boeing have been nothing short of breathtaking. Their business model is based totally on the hub concept, with limited point-to-point traffic, backed in each case by substantial national investment in airport infrastructure. The geographical position of the Gulf means that with modern aircraft there is virtually no inhabited place on earth which cannot be reached non-stop.

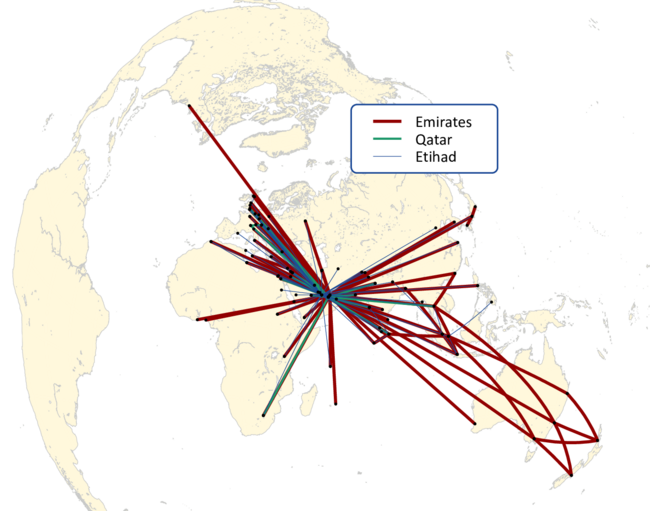

It is hardly surprising that the major US passenger carriers should be concerned. According to OAG, the three Gulf airlines currently (April 2015) have 170 flights per week to the US, including Emirates' fifth freedom service between Milan and New York, making the US their second largest market after the UK. Their total weekly seat capacity to the US at some 69,000 may represent just 7% of American, Delta and United's total international capacity, but it is of course growing rapidly. Even the current row hasn't stopped them, with several recent announcements by Emirates and Qatar in particular of additional flights to the US. At present Emirates and Qatar serve ten US destinations each and Etihad six.

But isn't this just déjà vu all over again? Some may recall that there was a time when KLM was a virtual pariah in the aviation industry for growing on the back of sixth freedom traffic; and then there was Singapore Airlines, which attracted substantial passenger flows between Europe and the Far East and Australasia over its hub. KLM and Singapore share several other characteristics with the Gulf carriers, including the strong backing of their governments, efficient, modern and ample airport infrastructure and small home markets. Plus ça change plus c'est la même chose, as the saying goes.

It is also the case that the US carriers are late coming to the party. Some European legacy airlines, especially Lufthansa and Air France-KLM, have been voicing their concern for over a decade. They have put pressure on their governments not to allow the Gulf carriers to add capacity to their home markets and have lobbied the European Commission to take action against alleged anti-competitive behaviour.

Similar arguments have been advanced by Air Canada, which strangely campaigned against Emirates' sixth freedom operations via Dubai while simultaneously launching Toronto and Vancouver as hubs for traffic to/from the US. The resultant Canada/UAE inter-government argument even spilled over into non-aviation areas, with the UAE threatening to restrict Canada's access to military facilities in the Gulf.

As in the US, there has been an absence of unanimity among European airlines. The UK has had open skies bilateral agreements with Qatar and the UAE for many years and has shown no interest in backtracking. All three Gulf carriers have extensive networks to the UK regions and multiple daily flights to London. IAG has refused to join Lufthansa and Air France in demanding action by governments and the European Commission, with Chief Executive Willie Walsh saying that he has no issue with competing with Emirates etc, “none whatsoever.”

IAG has even gone so far as to submit its own comments to the US State and Transportation Departments urging them to ignore the pleas of American, Delta and United. This reluctance to follow its fellow major legacy airlines pre-dates by some time Qatar Airways joining the oneworld alliance and investing in IAG.

We know the problem: What's the solution?

It is tempting to lump Emirates, Etihad and Qatar together, and they certainly share many characteristics, but it is also true that in certain respects Emirates is different from its two fellow Gulf airlines.

It has been established for longer, is significantly larger and perhaps most important of all for present purposes, does not receive overt financial support from its government owner. In May it announced that 2014/15 was the 27th consecutive year of profitability for the Emirates Group, with the airline recording a profit of $1.2bn, up 40% on the previous year, despite adverse currency movements. Passenger traffic was up 11% at 49.3m, on a seat capacity increase of 9%. Interestingly, the Americas region accounted for only $3.0bn in revenue, compared with $6.9bn for Europe and $6.7bn for East Asia and Australasia, but the Americas achieved by far the highest growth at plus 20%.

This is an impressive record for an airline established just 30 years ago in 1985 by Maurice Flanagan (who sadly died recently) with $10m of government money ($10m seemed “like a nice, safe sort of number” according to Flanagan) and instructions to “be good, look good, and make money.” Many analysts have forensically examined Emirates' books over the years and not one of them has ever produced a smoking gun.

There may be room for argument about other forms of state support, but no-one has successfully shown that Dubai hands over regular wads of cash to keep Emirates going.

Etihad and Qatar are different. They still receive money from their government owners on a regular basis and would not exist, let alone continue their rapid expansion, without such financial support. But they are still young airlines.

They argue that it is not unreasonable for owners to provide additional investment in the early years of a company's existence. Is there any major legacy carrier, anywhere in the world, they ask, that has not received government financial help in the past? After all, one man's state aid is another's investment financing.

Even in Europe, the argument goes, state aid is allowed, as long as it is provided on commercial terms. The key issue is whether the shareholders of Etihad and Qatar can reasonably expect an eventual return on their investments.

The fact is that the allegations of state subsidies and unfair competition with respect to the Gulf carriers have been countered with arguments about government support for European and North American airlines. Which side you believe, if either, probably depends on where you start from.

The whole debate has quickly become unproductive and shows few signs of going anywhere. How are adjudicators supposed to weigh the provision of direct financial support against the elimination of all debt through a Chapter 11 process (once described by then British Airways' CEO, Rod Eddington, as “back door state aid”)? It seems at times that the two sides in the debate are talking past rather than to each other.

American, Delta and United say that they are being completely reasonable. They are just asking for government to government consultations, as provided for under the open skies bilateral agreements.

But consultations are a means to an end, not a solution in themselves. The likelihood of governments being able to shed clarity on what is and is not state aid is remote. EU/US consultations on Norwegian International's application to operate trans-Atlantic services have failed to make progress, despite arguably involving less contentious issues.

Most bilateral air service agreements contain a “fair and equal opportunity to compete” clause, or a version of it. The vagueness of the phrase, with no accompanying definition, is deliberate because if the governments involved had been required to go any further, no ASA would ever have been signed.

Whether you call it clever drafting or obfuscation, the fact is that the clause now at the centre of a potential major diplomatic row between the US and Gulf countries was always recognised as a way of parking an insoluble problem.

If the US government representatives do meet their Qatari and UAE counterparts and fail to reach agreement, and it is difficult to see any other outcome, what next? The nuclear option would be for the US to give notice to terminate the two ASAs, but that hardly seems likely. Such a decision would certainly harm the interests of other US carriers such as Federal Express, and as in Canada, could well spill over into non-aviation areas, not something the State Department is likely to welcome in the current Middle East political climate.

(It is far from unknown for negotiations about ASAs to become entangled in other contentious issues. Some have drawn attention, for example, to the fact that in May, Qatar Airways secured additional traffic rights to France at the same time as the Government of Qatar agreed to purchase $7bn worth of French-built jet fighters. Only three months earlier the French Secretary of State for Transport had declared: “No more traffic rights will now be granted by France to the Gulf carriers.”)

The ASAs themselves provide for arbitration by an independent body, usually ICAO-appointed, in the case of disagreements, but past experience suggests that such an approach is almost invariably very expensive and can take several years, with no guarantee of success.

So what do the US carriers want?

So far American, Delta and United have mounted a noisy and well-funded lobbying campaign to win the argument with the US authorities about unfair competition. We know they feel hard done by. What is less clear is what they really want. The debate has generated considerable heat, but there is little sign of a long-term strategy. It is far from obvious what outcome the three US airlines expect or want. Writing in Forbes.com, Dan Reed suggests five possible explanations for their action:

- Seeing how much traffic their European partners have lost to the Gulf carriers, the US airlines are fighting to prevent the same thing from happening to them now that the three Middle East airlines are aggressively expanding service to major US cities.

- US carriers are acting in defence of their European alliance partners by opening up another front in the public relations and global legal battle against the rapidly expanding Gulf carriers.

- The leaders of American and United, which have less at stake strategically in the matter than Delta does, are allowing themselves to be led by the nose by Delta's CEO Richard Anderson, who was the first and is the loudest complainer among the Big 3's leaders.

- The Big 3 are using the Gulf carriers' modest market incursions to create a bogey man against which they can rail publicly as a way of distracting the public from the big — though still not remarkable on a net margin basis — profits the US airlines finally are earning.

- The fight against the Gulf carriers is a way to rally US airline labour groups to support a management that is seeking to protect US jobs, thereby making it difficult for labour to fight management for big raises and increases in benefits now that the airlines are making decent money.

It is possible to construct arguments in favour of each of these hypotheses, either separately or all together. They are plausible and yet not entirely satisfying as explanations for the behaviour of American, Delta and United, “because each theory relies on other people — judges, bureaucrats, politicians, and/or the travelling public — being extraordinarily gullible and easily persuaded to ignore significant counter arguments”, as Reed comments.

The Partnership airlines may have convinced themselves that following the examples of Europe and Canada, the US government will be persuaded at least to slow down the Gulf carriers' expansion plans in the US market. This worked for Lufthansa, Air France-KLM and Air Canada, but critically they all had restricted bilateral agreements with the Gulf countries.

It is far easier for governments to sit on their hands and decline to move than it is to actually take action, especially when the only legal way of restricting air services in the absence of binding arbitration is to terminate an international agreement. Following on from the Norwegian International saga, the US would risk establishing a reputation as a very poor bilateral partner, with unpredictable ramifications for its other open skies agreements.

And where would it all end? It can hardly be argued that the Gulf carriers are the only airlines in receipt of state aid.

With the growth of Chinese airlines, also expanding rapidly into the US market, will they be next on the hit list? That would send shivers down the spine of any Secretary of State. Until now it has been the Chinese who have resisted pressure from the US for an open skies ASA.

Perhaps in future the boot will be on the other foot. According to OAG data, Chinese airlines operated 140% more seats to the US in an average April 2015 week than they did in an equivalent period in 2010, compared to an 80% increase in US airlines' capacity.

And what about Turkey? Once the new airport is built in Istanbul, many believe that Turkish Airlines will be just as much, if not more, of a threat to European and US airlines as the Gulf carriers have become. It already flies to more countries than any other airline in the world. Will a campaign be launched against Turkey, situated on Europe's border, a potential EU member and a strong NATO ally? A can of worms doesn't really do justice to what could emerge.

Thus, it is difficult not to conclude that while the lobbying campaign by the Partnership for Open and Fair Skies has certainly generated considerable heat, there is little evidence of a long-term strategy with a clear objective. American, Delta and United, with their European counterparts, have focused the world's attention on a problem without identifying a way out of it. Yet potentially there are serious implications for the whole aviation industry.

It is worrying that many of the acknowledged benefits of liberalisation of international air services may be put at risk by a less than well-thought out campaign.

The risks

The current argument between a group of European and North American legacy carriers on the one hand and three Gulf airlines on the other has certainly uncovered some fault lines in the structure of the aviation industry.

Alliance partners have found themselves on different sides of the debate, reinforcing the impression for many that the current three major alliances are highly unstable and may not have a long-term future, at least in their present form.

In both Europe and the US there is a clear lack of unanimity among airlines, not to mention other parts of the aviation industry and consumer groups. Nowhere is this fracturing more evident than in the virtual disintegration of the Association of European Airlines. The AEA's problems cannot all be blamed on the row over the Gulf carriers; it has been experiencing internal tensions for many years. But the decision of the IAG airlines to follow Virgin Atlantic in leaving the organisation, then in turn followed by Alitalia and Air Berlin, has been a major blow.

It is almost a decade since Lufthansa and Air France-KLM began to complain about the aggressive expansion of the Gulf carriers into their home markets. Exactly the same arguments now advanced by their US counterparts were rolled out, albeit mostly behind closed doors and with far less supporting research.

The AEA was split, with British Airways and Virgin Atlantic resisting any protectionist moves. (Ironically, at the time Iberia, while not a major player in the debate, gave the impression of being more sympathetic to the Lufthansa/Air France-KLM case). Lufthansa and Air France-KLM made some progress with their own governments, succeeding in restricting the Gulf carriers' expansion plans at least for a time, but less so with the European Commission. The AEA itself was in a difficult position and unable to mount a united campaign on behalf of its members.

It is hardly unusual for representative organisations to have to deal with strongly held, disparate views among its members. They usually manage to cope, either by reaching compromises acceptable to most or simply saying that on certain issues there is no consensus and therefore the trade body cannot take a position. It is not obvious why this has not been possible in the AEA. Certainly there is intense commercial competition between members, but the fact is that on most aeropolitical issues they do manage to reach agreement.

Perhaps some view the problem of the Gulf carriers as just too important to ignore within the AEA, or perhaps some of the larger members simply feel that they are big enough to mount their own lobbying campaigns and therefore have less need for a body like the AEA. Whatever the reason, they may be making a major mistake.

The importance of ensuring that your views are known to and understood by the Brussels bureaucracy and political establishment should not be underestimated. Often the benefits come not from influencing the big debates, but from the myriad of smaller issues which daily plague airlines. Despite the progress made with liberalisation, aviation remains a highly political and regulated industry in which politicians and bureaucrats find it difficult not to meddle. Most observers would agree that a united industry is far more likely to achieve its objectives with governments and regulators than a divided one. It is too early to determine what the AEA's future might be, but it has clearly been weakened as a lobbying force.

IAG has announced that it will be joining one of the smaller Brussels-based airline trade bodies, the European Low Fares Airline Association (ELFAA), which somewhat disingenuously now describes itself as “the largest European airline group for passengers within Europe.” (There are actually four airline representative bodies lobbying Brussels, each one originally based on different airline business models.) It remains to be seen whether Ryanair and easyJet, the two principal founder members of ELFAA, and the IAG airlines can work constructively together. Certainly Virgin Atlantic's early membership of the International Air Carrier Association, which mostly represents leisure airlines in Brussels, was not a wholly successful experience.

Before the Gulf carriers became such a focus of attention, it was the AEA which took the lead in first producing and then promoting a trans-Atlantic aviation agreement going well beyond the US open skies model.

Essentially the Trans-Atlantic Aviation Area, later renamed the Open Aviation Area, proposed to extend the EU internal aviation market across the Atlantic, covering some 60% of scheduled air services in the world. Had it been agreed, it would have set in motion a momentum for liberalisation which could have transformed global aviation, not least in opening up at last the possibility of cross-border airline mergers and consolidation, a (the?) key factor in achieving sustainable profitability for the industry, as US experience has shown.

It did not succeed because the US Government, under pressure from domestic interests, especially the unions, was unable to deliver on the liberalisation of the critical airline ownership and control rules.

The EU/US agreement eventually signed in two stages followed the US open skies model which already applied to most air services between the US and Europe, although it did of course bring the UK, and especially Heathrow, into the picture. The failure to achieve “true” open skies was a disappointment to many, but at the time most observers saw it as a setback rather than an end to progress. The liberalisation bandwagon would surely continue to role and eventually common sense, and wider economic interests, would prevail. The European Commission remained committed to reforming the arcane ownership and control rules.

That all seems a long time ago, although it isn't. The focus of attention now is on rolling back liberalisation, not taking it to the next level. The likes of Lufthansa and Air France-KLM in Europe and American, Delta, United and Air Canada in North America may concentrate on the need for a “fair and level playing field”, whatever that might mean, but to many the reality of what they are seeking seems to be increased protection from the competitive threat presented by the Gulf carriers. Why else has all the attention been on the most successful airlines in recent years, at least in terms of traffic growth, and not on the many other carriers in places like China, India, etc clearly in receipt of substantial government largesse. The likelihood of opening up markets further is fast receding.

This is a very different regulatory and political environment to the one which existed only a relatively short while ago, and the implications are potentially very serious. The economic benefits of liberalisation are well documented; the economic disbenefits of increased protectionism are just as clear. As CAPA has remarked: “The issues raised go to the heart of US aviation policy post-Chapter 11... The [Partnership] paper puts the whole nature of open skies back on the table, with frightening potential for the negativity to ripple outwards, just as the positive movement did in the past.”

Traditionally airlines were very close to their national authorities, even where they were not actually state owned. There was rarely any real difference between the policies advocated by individual carriers and those actually adopted by their governments. It was an industry “riddled with protectionism and patronage, bail-outs and handouts”, in the florid words of The Economist.

This is still the case, of course, in some countries, but among the most significant changes in the industry over the past few decades have been the gradual move away from such close airline/government ties, the increased promotion of more competition and the more prominent role played by consumer interests. Some in the airline industry might look back to the old days with nostalgia, but most regard these developments as both inevitable and beneficial.

Yet the governments of Germany, France and the Netherlands, or at least their Transport Departments, were all quick to lend their public support to the campaign by their national airlines. They didn't seem to pay much regard to the interests of consumers, who give every indication of welcoming the increased competition provided by the Gulf carriers.

It is particularly surprising to see the Netherlands line up with France and Germany in this respect. After all, it was the Netherlands which once pursued precisely the same strategy as the UAE and Qatar in developing a successful hub airport at Amsterdam, and of course along with the UK, the Dutch were early proponents of liberalisation in Europe and open skies elsewhere. The AEA Trans-Atlantic Aviation Area model was even initially drafted by a former KLM employee. How times change.

Thus, on one level the campaign recently launched by the US Partnership for Open and Fair Skies might be viewed as little more than an irritant, perhaps a minor blip in the onward movement of the international airline industry from protected dinosaurs to global companies. However, this would be to ignore the very real dangers inherent in what has been released. A ripple on the pond could become a tsunami. The US carriers themselves may not have a clear or realistic picture of the outcome they want to achieve, but the risks to further liberalisation, the alliances and airline trade bodies are only all too evident.

Europe to Middle East, Asia Pacific and Africa

Source: AEA, Company Reports