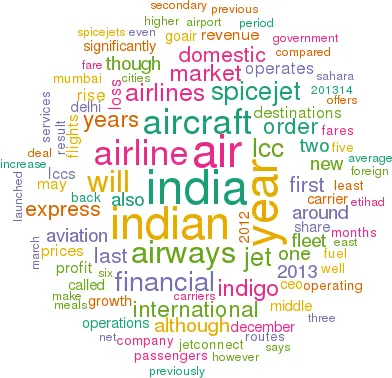

India's LCCs struggle through tough times

May 2014

The following tables reflect the current values (not “fair market”) and lease rates for narrowbody and widebody jets. Figures are provided by The Aircraft Value Analysis Company and are are not based exclusively on recent market transactions but more reflect AVAC’s opinion of the worth of the aircraft. These figures are not solely based on market averages. In assessing current values, AVAC bases its calculations on many factors such as number of type in service, number on order and backlog, projected life span, build standard, specification etc. Lease rates are calculated independently of values and are all market based.

| Fleet (orders) | IndiGo | SpiceJet | GoAir | Air India Express | JetKonnect |

| A320 | 78 (7) | 18 | |||

| A320neo | (160) | (74) | |||

| A321neo | (20) | ||||

| 737-700 | 5 | ||||

| 737-800 | 37 (17) | 17 | 4 | ||

| 737-900 | 2 | ||||

| 737-900ER | 6 | ||||

| 737MAX | (42) | ||||

| Dash 8 Q400 | 15 (15) | ||||

| ATR 72 | 5 | ||||

| Total | 78 (187) | 58 (74) | 18 (74) | 17 | 16 |

Note: The thickness of the lines represent the volume of capacity on each route. The area of thelarge circles relate to total domes c capacity at the top airports.