The long-haul low cost business model

May 2010

The next wave in aviation business models appears to be long–haul “low cost” operations. As usual there are proponents who claim that these will create traffic, rather than divert traffic from other networks, and thus provide a viable business model — and detractors who state that they can never work.

Of course the concept is not new. The oft–quoted example is that of Freddy Laker’s Skytrain of the late 70s/early 80s, with point–to–point low fare services on the Atlantic. (His operation failed in the tail–end of the 1981 recession not merely because of intense price pressure from the established IATA carriers but also because his debts were in Dollars and revenue and demand in Sterling when the pound revalued from $2.40 to $1.80).

However, even now such low cost operations are currently provided on leisure oriented routes by many (primarily European) charter carriers in their attempts to escape the LCC pressure within Europe. Notably, however, charter carriers have sources of demand and freedom of operational flexibility not usually available to scheduled operators.

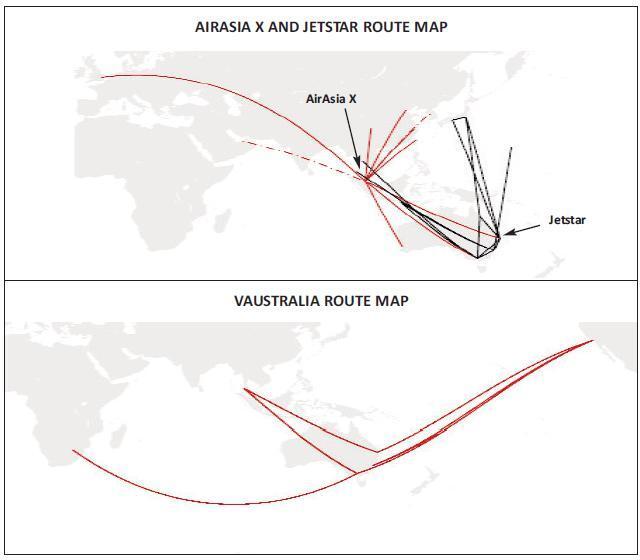

Meanwhile, in the Asia/Pacific region there are three recent new entrants into scheduled “long–haul low cost” operations: AirAsia X (linked to AirAsia — see pages 6–11), Jetstar (as a tag–on to its domestic Australian LCC operation and owned by Qantas), and VAustralia (owned by Virgin Blue). There were others – notably Oasis Hong Kong, which failed in 2008, and Viva Macau, whose AOC was withdrawn last month.

All seemed to adhere to many of the low cost principles of the Southwest short–haul LCC model:

- Start with a clean sheet of paper

- KISS principle (Keep It Simple – Stupid!)

- Single aircraft family

- High utilisation

- Point–to–point services only

- In–flight frills only at extra cost

- Operate to secondary airports where feasible

- Internet or call–centre reservations only (no GDS)

- Unpackaged fares, bag charges.

However, long–haul air transport is significantly different from short–haul. It may be disingenuous to state the obvious, but:

- The distances and the time taken up in cruise is substantially longer. The aircraft therefore naturally stays in the air for a far longer period of time, while turnaround times at the destination airports can be defined by time zone changes and curfews/ local timings. As a result there is by default less of a differential against established carriers on utilisation than available on a short–haul operation.

- Second, whereas the typical short–haul low cost operation will try to ensure that flight and cabin crews return home at night, on long–haul, with the flight and cabin crew reaching operational hour limits on a single flight, this is impossible and generates the need for hotac expenses, which further erode any potential operational advantage.

- Third, because of the length of time in the air you have to keep the passengers occupied and relatively comfortable – and the concept of comfort is important to the passenger when choosing a flight of more than six hours.

- Mathematically, in the absence of substantially lower aircraft ownership costs it will be exceedingly difficult to attain unit cost advantages over established legacy carriers anything near what is possible on short–haul operations.

- Even on short–haul operations as a start–up it can be difficult to promulgate the “brand” and the market offering at the end of a route. On long–haul the marketing at the other end starts to become very expensive.

- On point–to–point short–haul services you are normally competing with other forms of transport as well as established carriers. For long–haul services there will always be some network airline that will try to extract the marginal dollar through offering a seat through a hub.

- Long–haul fares by their nature will be higher and unlike short–haul ultra low cost flights are unlikely to be “impulse” purchases.

- Possibly most importantly, there are very few good purely O&D point–to–point long–haul markets sufficient to support reasonable frequencies on widebodied aircraft, meaning that whatever type of long–haul operation you operate you have to generate feed at both ends of the route. This naturally would be an anathema to the KISS principle as it creates complication. Having tried to lump these three Asia/Pacific widebody operators together as a single business model type, there are significant differences.

VAustralia is the long–haul offshoot of Virgin Blue, set up to take advantage of the open skies agreement between the US and Australia. It started operations at the beginning of last year and has four 777s, with possibly three more on order. It appears to be more of a traditional long–haul airline – redolent of Virgin Atlantic, on which it is undoubtedly modelled – operating a three class configuration of economy, premium economy and “business”, including lie–flat beds.

Initial routes involved the three main eastern Australian cities (Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne) to Los Angeles, and it has tacked on Phuket, Fiji and Johannesburg. It has built interline agreements with a bundle of carriers in the US (including Delta, Continental, Alaskan, and of course Virgin America), naturally links its booking engine with Virgin Blue and Pacific Blue, and hardly surprisingly has interline links with Virgin Atlantic. (Intriguingly it even offers one–stop connections to London via Johannesburg, linking on to Virgin Atlantic services). Inflight services are traditional rather than unbundled low cost.

Jetstar’s international A330 operations are an integral part of the Qantas subsidiary rather than a separately branded standalone operation – adding perhaps some complexity to the traditional LCC model. Here Qantas is able to use its daughter company to operate the outbound leisure oriented point–to–point services from the main Australian conurbations and also attack point–to–point services to the main inbound leisure destinations (such as Japan–Gold Coast) that Qantas itself is unable to operate profitably.

It currently has a fleet of seven A330s in operation – but 15 787s on firm order with another 50 on option. It operates a two class configuration – economy and a premium economy “Star Class” (with a modest 38” seat pitch). In–flight services (including entertainment) can be bought in standard economy – following the normal LCC concepts – but it does allow intraline (and interline) booking for connecting flights on its and Qantas’s networks. There are some suggestions that Jetstar Asia (its affiliate in Singapore) would like to get its hands on some of these widebodies in order to start longer haul operations itself.

In contrast AirAsia X tries to follow the classic LCC model. Based at Kuala Lumpur’s LCC terminal it can naturally link in to its own short–haul network, but doesn't: it leaves the passengers to try to work it out for themselves.

Operations started at the back end of 2007 with a leased A330 (on a two class configuration) operating between Kuala Lumpur and the Australian Gold Coast. By 2009 it had built a fleet of eight A330/340s with a route network encompassing London Stansted, Abu Dhabi, Chengdu, Tianjin and Hangzhou in China, Taipei and Melbourne, Perth and the Gold Coast in Australia. It has a further 20 A330s and 10 A350s on order.

The others ...

The on–board offering follows the unbundling inherent in the short–haul operation. Premium passengers get a meal and 15kg free luggage allowance, but economy passengers have to pay for all extras. True to form it has no alliance links or interline agreements, although anecdotally the route into Stansted gains and provides feed onto the Ryanair network. Others have tried and many have failed. Oasis Hong Kong had the ambition to run a low cost long–haul operation – citing the potential of stimulating outbound travel from China in particular. Its initial route structure was Hong Kong to London Gatwick using a couple of ex–SIA 747s. It had ambitious plans to develop routes to Vancouver, Chicago, Oakland, Berlin, Cologne, Milan and linking to others' low cost short–haul bases. Zoom also had a reasonable operation on both sides of the Atlantic (thanks to the owner’s dual nationality). But both these failed during the upswing in fuel prices.

Viva Macau also had ambitious plans. Operating under a concession agreement from Air Macau it operated 767s on routes to Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta, Melbourne, Sydney and Tokyo Narita. It failed last month, having run out of cash.

These three however did not have the backbone of a successful, profitable and cash generative short–haul low cost model to support the more fickle demands of longhaul operations.

Are these viable business models? In the end they may well represent the next stage in development of the new model airlines. It could well be that passengers will learn to create their own inter- and intra–line connections and spell the potential demise of the traditional network hub operation. It may well be that such offerings will substantially stimulate the market: after all, all that is being emphasised is that the airline industry is a commodity.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jetstar | |||

| A330 | 7 | ||

| 787 | 15 | 50 | |

| AirAsia X | |||

| A330 | 6 | 20 | |

| A340 | 2 | ||

| A350 | 10 | 5 | |

| VAustralia | |||

| 777 | 4 | 3? |