AMR: A Chapter 11 risk or one of the likeliest survivors?

May 2008

American, the world’s largest airline in terms of traffic, is seen by many as a Chapter 11 risk in a prolonged recession, given its labour cost disadvantage and pension exposure. But AMR also possesses significant strengths, including a diversified global network, powerful FFP, huge cash reserves and a range of non–core assets that could be monetised. How does the management plan to tackle this year’s challenges? And could an immunised American/BA alliance become a reality?

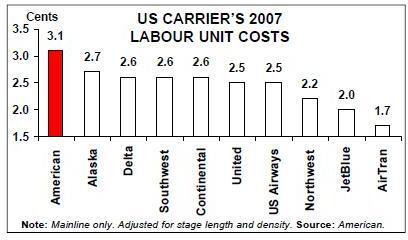

AMR is the only one of the "big six" US network carriers to have avoided Chapter 11. While that is something to be proud of, it has become a negative for AMR as its four largest competitors have gone through bankruptcy restructurings in the past few years. Delta, Northwest, UAL and US Airways have all used the Chapter 11 process to slash their labour and aircraft ownership costs and shed their pension obligations. This has resulted in American having the highest labour costs in the industry.

Like Continental (which last visited Chapter 11 in the early 1990s), American also has the more burdensome defined benefit pension plans, though those costs are manageable as a result of new pension legislation. Because of the cost disadvantages, AMR is headed for what is likely to be the worst loss margin among the US legacies in 2008. If fuel prices remain at the current levels, this year’s net loss could exceed $2bn.

To make the situation worse, American’s pilot contract is now open and the union is demanding substantial rises. AMR could therefore find it hard to work with labour to pursue cost savings that are needed to offset fuel prices and potentially softening demand and unit revenue trends.

Consequently, AMR is the only legacy carrier that could benefit significantly from Chapter 11 (many of the others would probably end up liquidating if they had to file for bankruptcy again). In addition to labour cost savings, American could reap aircraft savings, given recent trends in lease rates and aircraft values, and eliminate unsecured debt.

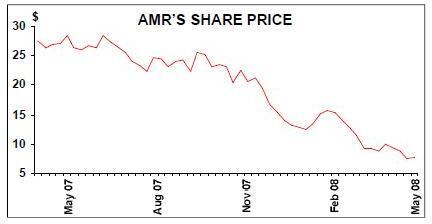

In recent months AMR’s shares have been trading at what one analyst called "near–bankruptcy" levels (see chart, right), as investors have evidently considered Chapter 11 a likely eventual outcome — say, in early 2009. But AMR’s top executives have made it very clear that they are determined to avoid it.

AMR came very close to filing for Chapter 11 in the spring of 2003, averting it only when it secured $1.8bn of annual labour concessions literally on the courthouse steps. It was a painful experience for both labour and management and involved the resignation of the popular chairman/CEO Don Carty. Gerard Arpey, the current CEO, noted in AMR’s recent earnings conference call that the company demonstrated in 2003 how hard it was willing to work to avoid Chapter 11 and that it has been "very mindful of that experience".

AMR has numerous strengths that will help it avoid Chapter 11 in all but the most dismal of fuel and economic scenarios. First, it has ample liquidity: almost $5bn in cash (as of March 31st), or 21% of last year’s revenues. AMR had the wisdom to build cash reserves and reduce debt when the capital markets were strong.

Second, AMR is well positioned to raise additional funds. Debt reduction has increased the pool of unencumbered aircraft. There are attractive non–core assets that could be monetised; in addition to the recently announced sale of asset management unit American Beacon Advisors, which will raise $480m, AMR is likely to put its regional subsidiary American Eagle on the block. There are assets that could be used as collateral, such as Heathrow slots. And if the going gets really tough, AMR might even attract a minority investment from its oneworld co–founder and transatlantic partner BA.

As rating agency Fitch noted in a recent report, AMR’s strong cash position and large unencumbered asset holdings "provide considerable room to manoeuvre in a prolonged industry downturn".

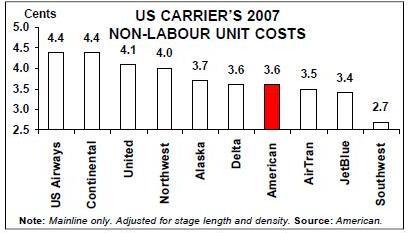

Third, while AMR has a labour cost disadvantage, it is not that dismally positioned in terms of its total cost structure. While its competitors slashed labour costs in Chapter 11, AMR quietly achieved the industry’s best non–labour cost reductions — an impressive $4bn of annual savings as part of its "Turnaround Plan" in 2003–2007. This was in addition to the $1.8bn voluntary labour cost savings.

Fourth, AMR has exercised considerable capacity restraint for years — long before other legacies began to see merit in the idea. Its latest plan envisages a near- 5% domestic contraction in the fourth quarter.

Fifth, in response to $110–plus oil, AMR has smartly decided to accelerate MD–80 retirements. It is now taking as many as 70 737–800s in 2009–2010. This will help offset the unit cost increase resulting from reduced capacity. To offset the higher capital spending, AMR is clamping down on all non–aircraft capex.

Like its peers, AMR is taking action on multiple fronts. There are new efforts to boost ancillary revenues, a management and support staff hiring freeze and countless other cost and revenue initiatives. Finally, AMR’s size and network strengths mean that it is not under pressure to play a major role in industry consolidation. It has been able to stay on the sidelines, focusing efforts on this year’s real challenges, while keeping a lookout for any great opportunities and exploring less risky deals such as alliances.

The fuel cost challenge

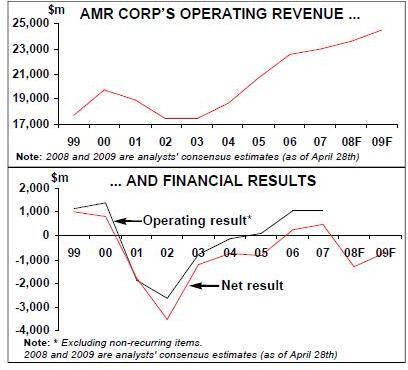

AMR returned to profitability in 2006 (like most other US carriers), following five years of net losses totalling $8.1bn. 2006 and 2007 saw net profits of $231m and $504m, respectively. Last year’s operating margin was 4.7% — at the low end of the range for the legacy carriers.

AMR’s recovery was almost entirely due to the $5.8bn Turnaround Plan cost savings, though an improved domestic revenue environment in the past two years also helped.

American’s ex–fuel unit costs declined by 17.4% between 2002 and 2007. However, because the average fuel cost almost tripled in the five–year period, total CASM increased from 11.54 cents to 11.98.

Like the rest of the industry, AMR plunged back into losses in this year’s first quarter, when oil prices surged to the $110- plus range, though AMR’s 6% pretax loss margin was actually better than the legacy average. The airline had good revenue performance and kept non–fuel expenses in check, but its average fuel price per gallon soared by 48%, increasing fuel costs by $665m. RASM was up by a healthy 6.5%, but it nowhere near compensated for the 15.8% increase in CASM.

The problem now is that fuel prices look likely to remain at extremely high levels for the foreseeable future. AMR faces CASM headwinds in light of the reduced capacity, and demand and RASM trends are expected to weaken due to recession (though so far there are no signs). AMR is currently expected to post a loss of almost $1.3bn for 2008 (consensus estimate as of April 28th), though the range of individual analysts' estimates is rather wide.

According to a fuel–sensitivity analysis carried by Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg (April 23rd), at $100 oil, AMR would have a net loss of about $1bn in 2008.At $110 oil, AMR would lose $1.7bn; at $120 oil, the loss would be $2.4bn; and at $130 oil, about $3bn.

Whichever of those scenarios materialises, as Arpey put it, AMR needs to "right the revenue–cost equation" but "there is certainly no silver bullet to the problem". The company has continued hedging for fuel; it has a useful 29% of its 2008 fuel needs capped at about $75 per barrel. Like its peers, AMR has put much effort into developing ancillary revenues; most recently, it followed UAL and others in introducing a $25 fee for a second checked bag domestically. But the only effective solution is to raise fares substantially — and, realistically, that is unlikely to happen in the domestic market without a significant capacity reduction.

Domestic contraction, modest international growth

AMR has been very conservative in managing its capacity for several years — even its international growth has been disciplined compared to the other legacy carriers.

What was thought to be a conservative plan for 2008 has already been revised down twice this year in response to oil. The latest changes, announced on April 16, pull down domestic capacity in the second half of this year and also reduce regional flying.

American’s mainline capacity is now slated to fall by 1.4% in 2008, which will include a 3.6% reduction in domestic ASMs and 2.5% growth internationally. Regional affiliates' capacity will decline by 2.1%. The biggest impact will in the fourth quarter, when mainline domestic capacity is expected to fall by 4.6%. This is in line with the other legacies' capacity cuts.

But since those plans were formulated before oil surged above $115, further domestic capacity cuts (by all of the airlines) are likely. American has significant flexibility on that front because of the 300 MD–80s still in the fleet. This year’s cuts will also be achieved through the return of three A300s as their leases expire.

In the first place, American will be eliminating some of its more marginal longer–haul domestic flying. It is ending service to Oakland (California) in September. This year’s modest international expansion will include a new Chicago–Moscow route and linking JFK with Barcelona and Milan. American’s domestic/international ASM split, which is currently 63%/37%, will obviously continue to shift in favour of international operations.

American’s main response so far to the EU/US open skies regime has been to terminate operations to Gatwick, in favour of focusing on Heathrow (with one daily flight to Stansted). The airline has moved its three daily Gatwick flights to Heathrow (after obtaining a few additional slots there), which has given its main hub at Dallas Fort Worth its first LHR link. Even though American has extensive service to continental Europe from the US, Heathrow represents about half of its transatlantic capacity.

Accelerated fleet renewal

American operates a relatively old mainline fleet, averaging about 15 years in age. At year–end, the 655–strong fleet was made up of 47 777–200ERs, 58 767–300ERs, 15 767–200ERs, 124 757–200s, 34 A300- 600Rs, 77 737–800s and 300 MD–80s. Inaddition, there were 47 non–operating aircraft — mostly MD–80s that had been permanently grounded and were held for disposal.

The main challenge is replacing the MD–80s, which account for nearly half of the fleet and have an average age of over 18 years. The process began in March 2007, when American announced its intent to pull forward the delivery of 47 737–800s from their 2013–2016 delivery schedules into the 2009–2012 timeframe — possible because of an earlier flexible long–term purchase contract with Boeing. But last year American accelerated the delivery of only about 12 737–800s, because financial restraint was the name of the game. The leadership stressed the need to be very careful about allocating further capital until there was certainty of getting a return on that capital.

The breaking point was $110–plus oil. American announced on April 16 that it had decided to accelerate the MD–80 retirements and 737–800 deliveries, as well as place new 737–800 orders. The plan now is to take 34 737–800s in 2009 and 36 in 2010, compared with a total of 26 in those years previously, though all of those are not yet firm orders. The move reflected the realisation that, at the current oil prices, American can get a very clear ROI on the 737–800 in the near–term, though CEO Arpey also noted that the date of Boeing’s next–generation narrowbody keeps moving into the future.

The downside is that the new strategy will shift the main capital spending burden from the 2011–2016 period to the immediate future — just when liquidity may become an issue. The new plan would increase 2008–2010 aircraft commitments by around $1.3bn, from $787m to over $2bn.

But there is obviously much flexibility. The MD–80 replacement process will take a while because of the sheer size of the fleet, and the retirement schedule can be adjusted to suit market conditions. There is strong demand for the 737–800 globally, so getting out of any orders or doing sale–leasebacks should not a problem.

American also has leases expiring on 21 A300s in 2009–2011.

As for the international fleet, American, like some of its peers, faces the challenge of finding timely replacements for its ageing aircraft, given the manufacturers' order backlogs and delays to new aircraft. Currently AMR has orders in place for only seven 777s, for delivery in 2013–2016. Because of the long lead times, the airline should be placing more orders immediately, if it wants to continue expanding internationally. By 2015, its 15 767–200ERs will have an average age of 28 years, its 58 767–300ERs will be 21 years old and its 124 757–200s will average 20 years. One can only assume that AMR can count on its special relationship with Boeing to resolve those challenges.

Balance sheet considerations

AMR has made great progress in repairing its balance sheet since 2003, even though it remains highly leveraged.

Net debt (debt minus cash reserves) has declined by 43% in the past five years, from $18.9bn at the end of 2002 to $10.7bn as of March 31st — the lowest level since 1998. The cash position peaked at $5.9bn a year ago (26% of annual revenues), though the balance has declined to $4.9bn (March 31st) mainly because AMR has been prepaying debt. Last year alone, total lease–adjusted debt declined by $2.3bn to $15.2bn.

AMR has completed some well–timed share offerings and debt refinancings. Most significantly, in early 2007 it raised almost $500m by selling equity at close to $40 a share — a level that turned out to be the five–year peak for the share price. The stock has since declined steadily and has been trading below $10 in recent months.

Those efforts have meant that AMR is now in a better shape to endure a tough fuel and economic environment than it was just a few years ago. (It is amazing to think that in the past two years AMR was criticised for hoarding cash. Only six months ago it was under pressure from investors to pay a dividend.)Near–term obligations appear to be manageable. This year’s scheduled debt and capital lease payments are $1bn, including a $300m convertible debt payment. The pension cash contribution is estimated at $350m. Capital expenditure is expected to be $1.2bn, including $600m in pre–delivery payments on 737s.

On the negative side, AMR is likely to violate the fixed charge covenant related to its $439m credit facility term loan this year, possibly even in the current quarter. Like Northwest and UAL recently, it will have to negotiate new terms with its lenders — either paying onerous consent fees or having to tap into its cash reserves to repay the loan.

AMR is fortunate in that it is currently not required to maintain any reserve under its credit card processing agreement, but there are no guarantees this will be the case in the future.

JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker suggested in a mid–April research note that the only real trigger for a Chapter 11 filing by AMR would be liquidity (as opposed to the need to get cost savings). Based on his 2008 loss forecast, and assuming no additional liquidity raising, Baker estimated that AMR would have $3.1bn cash at the end of 2008, which would probably be adequate. However, if fuel prices remain at current levels and no funds are raised in addition to the Beacon sale, unrestricted cash could approach $2bn in 2009, which Baker considers AMR’s minimum bankruptcy filing threshold.

Asset monetisation potential

So raising liquidity will be the key. AMR is fortunate in having large unencumbered asset holdings that it could sell or put up as collateral. Raising funds through asset sales will be easier for AMR because of the strategic review that the company launched — for a different reason — in the early autumn of 2007. At that time certain equity investors, unhappy about share price trends, were trying to spur the largest US airlines into taking concrete action to create shareholder value. American faced pressure from FL Group, one of its largest shareholders, to spin off its FFP and other non–core assets.

In other words, while the purpose of asset sales may have changed from enhancing shareholder value to raising funds for survival, the important thing is that AMR already has a pretty good idea of which non–core assets might be the easiest to separate and sell, raise adequate proceeds and result in minimal damage to the core business.

The process started last month, when AMR announced the sale of its wholly owned asset management subsidiary, American Beacon Advisors, to investment funds affiliated with two private equity firms for $480m. The primarily cash transaction is expected to close this summer. CEO Arpey noted that finding the right buyer took a while and that the agreement reflects the full value of the unit for AMR shareholders. AMR is retaining a 10% stake in Beacon, enabling it to benefit from the growth of the high–margin business, which earned a $48m pretax profit on $101m revenues in 2007 (both up by 40%).

AMR is still hoping to divest its wholly owned regional unit, American Eagle, by year–end. The decision to shed Eagle — either through a spin–off to AMR shareholders, a sale to a third party or an IPO — was first announced in November 2007, when the value was estimated at between $600m and $1.1bn. The move would seem to make sense to both parties. It would put American in step with other large carriers that have shed their feeders, enabling it to focus on core operations and save costs in the longer–term through the use of outside contractors and the competitive bidding process. Eagle, in turn, would be better able to pursue growth opportunities outside AMR, while retaining a service agreement with AMR for some years at least.

Eagle is a large airline, with revenues of $2.3bn in 2007 and a fleet of 300 aircraft and a network of 150 cities at the end of 2007.

AMR has been laying the groundwork for its separation for many years, as a result of which Eagle is fully capable of standing on its own. It has a separate management and has produced independently audited financial results for several years. Last year AMR and Eagle revised their agreement to reflect market–based rates, but Eagle was still able to earn a $114m pretax profit (5% of revenues) in 2007. Another small regional business, Executive Airlines, which serves the Caribbean, is included in the planned divestiture.

But Eagle does have some cost issues, especially high labour costs, which are mainly due to the seniority of its workforce. And there is the thorny issue of a large fleet of 50–seat RJs, which were in excess supply long before the current fuel environment (as legacy pilot scope clauses have been relaxed and 70–100 seat RJs have gained popularity). It is a tough market to sell regional carriers, but AMR will probably try because it may not get any easier in future years.

The original list of divestiture candidates also included AAdvantage FFP and AMR’s MRO business. But separating the maintenance business was always considered to be many years away, because even though there is potential to develop third–party revenues, today the vast majority of AMR’s MRO business is still from American. As for the FFP, AMR is unlikely to want to shed that business in the current environment because of the cash flow it generates. In any case, separation of the FFP poses tricky issues that probably require further study.

The labour challenge

American faces serious problems on the labour front. First, it has uncompetitive labour costs because its workers are the highest–paid in the industry. Second, all of its labour contracts are now open and the workers are demanding immediate substantial pay increases. Third, its labour relations are so strained that strikes cannot be completely ruled out.

The problems date back to the labour concessions that American secured on the courthouse steps in May 2003. All of the contracts became amendable on May 1.

The key unions are determined to roll back the concessions. American, of course, cannot afford that because of its labour cost disadvantage, weakening financial position and all the uncertainty about fuel prices and the economy. The situation is aggravated by the large bonuses collected by AMR’s top executives in the past two years. The workers must be angry and dismayed to think that they missed a two–year profit window. A year ago the pilots, represented by the independent Allied Pilots Association (APA), put forward outrageous pay and bonus demands, which would have meant a near- 50% increase in their total compensation this month. This was rejected by the management.

The talks, which started in 2006, have made no progress whatsoever. The two sides are so far apart that the National Mediation Board has been unwilling to get involved, despite APA’s requests. APA has alleged that the management is delaying the process. The pilots recently started staging protests at airports.

American’s traditionally militant flight attendants are also keen to get a new contract in place. The union recently elected as their new president a leader of their 1993 strike, who has since promised to get the 2003 concessions back "with interest".

It is hard to see how these issues can be resolved. One can only hope that the management will behave responsibly (decline any further bonuses) and that the unions will keep in mind that AMR does have the last–resort option of a Chapter 11 filing, which would solve many of these problems.

It will be a shame if the situation remains in limbo, because it would further weaken morale. American recently experienced a serious spate of flight cancellations due to MD–80 wiring inspections (which will mean a financial hit in the "high tens of millions of dollars" in the current quarter). There have also been reliability issues. Last month the pilots reportedly declined to participate in meetings aimed at improving customer service and operations. AMR needs the full cooperation and goodwill of its workforce to meet this year’s challenges.

An immunised AA/BA alliance?

At this point it looks like AMR is not going to participate in any major way in US industry consolidation. AMR’s official position is that that it does not need to take part in a big merger to stay competitive, that it "may or may not participate" in consolidation, but that it would be alert to opportunities to buy assets.

AMR’s network strengths include strong hubs at Dallas Fort Worth and Miami, extensive Latin American operations, a strong transatlantic presence (including Heathrow), a highly competitive position in the key business markets in the US — including Chicago, Los Angeles and New York (all of which have global service), the most powerful FFP in the world and membership of oneworld, which AMR’s management believes represents "the best global airlines and brands". So AMR believes that it will remain competitive irrespective of any consolidation that occurs.

Also, AMR is not a good potential merger candidate because of its large size, relatively high costs and difficult labour relations. AMR could gain by doing nothing. Its management believes that the Delta- Northwest merger, if it takes place, will lead to higher labour costs for the combined carrier, thereby narrowing AMR’s labour cost disadvantage.

But if there were to be Delta–Northwest and UAL–US Airways mergers, AMR would fall from being the largest US airline to the third largest, so it would probably want to do something to strengthen its position.

One obvious strategy would be to strengthen links with BA. AMR and BA are at a competitive disadvantage on the transatlantic vis–à-vis the other alliances (Northwest–KLM and Delta–Air France) because they lack antitrust immunity, which would allow them to coordinate their pricing, schedules and service as if they were one company. They have twice failed to secure antitrust immunity because BA could not agree to the Heathrow slot divestitures required by the European regulators. The problem has been their large market share on US–UK routes and BA’s dominant position at Heathrow.

But BA and AMR may have a stronger case now, first, because more competitors have gained access to Heathrow as a result of the EU–US open skies treaty. Second, the DOJ has given tentative approval for NW/KL and DL/AF to combine into a four–way transatlantic JV.

Therefore some kind of a compromise solution might be possible soon that would give AA/BA the all–important antitrust immunity. According to Arpey, it has been a continuing subject of discussion between the two airlines. "Speaking from American’s perspective, I think there will be an appropriate time to cross that bridge."

In recent weeks it has emerged that Continental is in early–stage talks on a marketing alliance with BA and AMR. This could create potentially a very powerful and profitable three–way transatlantic alliance, with an incredible position in New York and unbeatable connections to Latin America, but there would be added regulatory hurdles.