JAL: "Last chance for self-resuscitation"

May 2007

Japan Airlines (JAL), Asia’s largest carrier, has embarked on a major new cost–cutting and restructuring effort as part of its 2007–2010 "medium- term revival plan", announced in February. The aim is to restore profitability and position the company for post–2009 growth through measures such as staff and wage cuts, fleet downsizing, a shift to high–profit routes and the restructuring of non–core businesses.

When announcing the plan, JAL’s president Haruka Nishimatsu called 2007 rather dramatically the carrier’s "last chance for self–resuscitation". He was not suggesting that JAL could go bankrupt — or at least that would be an unlikely scenario. Even though JAL was fully privatised in 1987 and is listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), it has continued to have access to government–backed funding.

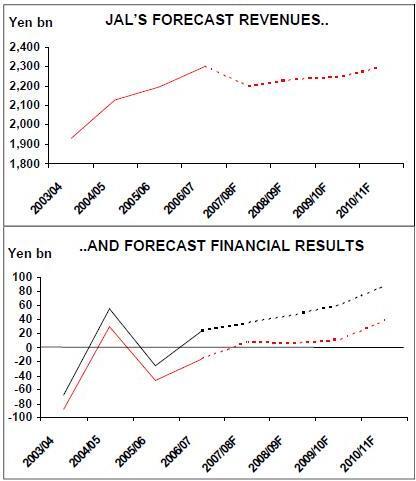

Although JAL has a weak balance sheet, it is not actually posting heavy losses. Rather, the airline is seeing persistently weak operating results — small losses or marginal profits — and has not paid dividends since 2004. After a promising Y56bn (US$472m) operating profit in FY2004/05 (2.6% of revenues), there was a marginal Y27bn (US$227m) operating loss in FY2005/06 (1.2% of revenues). In the latest financial year ended March 31, 2007, JAL earnt an operating profit of Y22.9bn (US$193m), just around 1% of revenues of Y2,302bn. However, JAL disclosed on May 2 that, because of a decision to remove Y44.7bn of deferred tax assets from the FY2006/07 balance sheet and some extraordinary charges, it would report a net loss of around Y16.2bn (US$136m) for 2006/07, which it did on May 9, rather than a net profit of Y3bn, as had been previously expected. In other words, JAL has now posted net losses for two consecutive years.

JAL’s results certainly contrast with the relatively healthy earnings achieved by All Nippon Airways (ANA) and many other large Asian carriers in the past couple of years, as demand in the Asia- Pacific region has strengthened and domestic business travel in Japan has bounced back. ANA is anticipating a Y74bn (US$623m) operating profit on revenues of Y1,290bn (US$10.9bn) for 2006/07; the 5.7% operating margin would be similar to the previous year’s 5.9%.

It is a point of concern that JAL has been trying hard to cut costs and improve its financial results since early 2005, when fuel prices first surged, but all of those efforts have failed.

Furthermore, in the past couple of years JAL has lost domestic market share, particularly premium passengers, to ANA and other competitors. This was largely blamed on a series of safety lapses in 2005, which did not result in fatal accidents but caused a loss of passenger confidence. There was a sharp traffic decline, which led to the resignation of Isako Kaneko as chairman in May 2005. Although JAL’s total traffic had recovered by mid- 2006, its premium passenger share has still not returned to the pre–2005 level.

As a result, JAL’s share price plummeted in the spring of 2006, from the Y300–325 level it had hovered at for two years to below Y200. The price remained weak for the rest of 2006 but recovered to around Y260 in January/February, when JAL began releasing details of the new restructuring effort. Since then the shares have again fallen steadily — the price was Y228 on May 4.

All of that has made JAL’s investors very unhappy. The key shareholders — who play a much more active role in JAL than the typical institutional airline investors do in the US and Europe — demanded the resignation of president/CEO Toshiyuki Shinmachi in the spring of 2006 (the second JAL leader they have forced out — the first was Akira Kondo in 1998). When the current president/ CEO Nishimatsu, formerly SVP finance at JAL, took over last year, JAL’s largest individual shareholder Eitaro Itoyama (who held a 4% ownership stake at that time) reportedly stated that the new chief executive would also have to go if he does not improve JAL’s results and restore dividends.

But there is now more at stake. What Nishimatsu meant with the "last chance" remark was that if the current restructuring does not succeed, shareholders are likely to demand radical changes, such as hiring an outsider — even a non- Japanese — as chief executive and bringing in a younger and more entrepreneurial board of directors. Such changes would be a major shock for a traditional Japanese company like JAL — though, of course, they might be a good idea anyway in light of future challenges such as increased competition from LCCs.

Not surprisingly, the new plan has had a mixed reception in the financial community. There is consensus that JAL is on the right track in terms of the types of changes it is trying to implement, but many analysts question whether the plan is achievable, given JAL’s recalcitrant labour unions and its history of disappointing restructuring efforts. Some analysts also question whether the plan includes deep enough structural changes to enable JAL to survive and prosper in competition with more nimble and aggressive carriers. In the first place, is it already too late to recapture premium traffic lost to ANA, given that many of those passengers have joined ANA’s FFP?

Then again, the greatest concern for many analysts and investors has been JAL’s weak cash position and balance sheet. Those fears were at least temporarily soothed by the new Y60bn (US$505m) financing obtained in March, which enabled the airline to launch the planned restructuring.

Goldman Sachs summarised its optimistic long term view on JAL as follows in a February research report: "Over the long term, we believe significant restructuring upside remains, and expect the stock price to rise again once asset sales and new borrowings allay concern regarding cash flow and as monthly operating indicators begin to show improvement. We maintain our Buy rating."

The timing of this plan is critical for JAL, because there will be major growth opportunities — as well as increased competition from LCCs — when expansion projects are completed at Tokyo’s Haneda and Narita airports in 2009. In particular, the opening of a fourth runway at Haneda in December 2009 will be a watershed event. To capitalise on those opportunities, JAL must restore decent profitability and repair its balance sheet.

The competitive scene

Unlike its counterparts in other regions, JAL cannot blame LCC competition for its ills. Although there are growing numbers of LCCs on intra–Asian routes, Japan’s highly restrictive bilateral agreements and severe airport capacity constraints have ensured that JAL and ANA have minimal exposure to new entrants.

Until the mid–1980s, the Japanese aviation policy was governed by the so–called "45/47 aviation constitution", which made JAL the country’s only scheduled international airline but permitted it to operate trunk routes between five domestic points. ANA was the main domestic carrier, though it was also allowed to operate short haul international charters. Toa Domestic Airlines (a predecessor of Japan Air System, which merged with JAL in 2002) was permitted to operate domestic regional and local routes.

The 45/47 system, which had somewhat eroded over the years, was formally abolished in 1985, meaning that JAL lost its scheduled international monopoly and the domestic market was opened up to competition. This paved the way for the complete privatisation of JAL in November 1987, when the government shed its 34% stake in the airline. Both JAL and ANA grew rapidly in the 1986–1992 period, expanding into each other’s territories. (JAL was also able to continue adding new long haul international destinations, thanks to the relaxation of ASAs with the US and other countries.)

However, there was no effective fare competition; the government had continued to set the basic domestic fares and airlines were permitted to offer discounts of up to 25%. In 1996 the government put in place a new zone fare system, which gave airlines unprecedented pricing freedom. But the outcome was disappointing: JAL and ANA introduced some discounts but raised off–peak fares in many markets; overall, prices rose. As a result, the government signalled that it would welcome new entrants.

There was a flurry of start–up activity in the late 1990s, giving Japan its first new airline entrants in over 40 years. The newcomers included Skymark Airlines, a Tokyo–based 767–300ER/737–800 operator, and Air Do, a Hokkaido–based 767/737–400 operator (also known as Hokkaido International Airlines), both of which began flying in 1998. Since then at least two other LCCs have taken to the air: Skynet Asia Airways (formerly Pan Asia Airlines), a Fukuoka–based 737–400 operator (2002), and StarFlyer, a Kitakyushu–based A320 operator modelled after JetBlue (March 2006).

These LCC entrants have entered many key domestic markets that were previously the exclusive domain of JAL and ANA. About one fifth of the 50 or so domestic routes out of Tokyo Haneda — a vital part of the business for any self–respecting Japanese airline since 62% of all domestic traffic goes via that airport — now have three operators. Another 13 or so routes have two airlines (typically JAL and ANA), so overall, about half of the domestic routes out of Tokyo now have competition. That said the new entrants operate extremely low frequencies out of Haneda and therefore have minimal competitive impact. They have captured only a 6% share of total domestic traffic, with ANA accounting for 48% and JAL 46%.

The main problem has been a chronic shortage of capacity at Haneda, the only domestic airport serving Tokyo. The opening of the second and third runways there in 1997 and 2000 gave the new entrants only a handful of slots. Even though more slots became available when JAL and JAS merged in 2002, the start–ups have not been able to offer sufficient frequencies on trunk routes. They need critical mass to achieve profits. They also face high start–up and fixed costs, which has led to strategies such as hiring foreign pilots and contracting out maintenance and crew training overseas.

Subsidiary-building and the JAS merger

Haneda’s fourth runway will dramatically increase slot availability, boosting maximum daily round trips by 43%, from 391 to 557. All airlines will benefit, though it remains to be seen if the new entrants will be able to increase their market share since Haneda also features prominently in JAL’s and ANA’s post–2009 expansion plans. When the extra slots become available, JAL wants to boost its domestic frequencies and add new short and medium haul international routes using smaller aircraft. JAL and ANA have been able to continue to dominate the Japanese aviation scene also because they have set up numerous new airline subsidiaries to cater for different market niches. In the 1990s the government, while trying to liberalise the domestic market, also sought to make Japanese carriers more competitive internationally. JAL’s and ANA’s unit costs were roughly twice as high as those of their Asian rivals, so the government urged them to set up low–cost "Asia–brand" and charter subsidiaries and forge more cooperative deals with foreign airlines.

Consequently, JAL set up many new airline subsidiaries or re–engineered existing units into viable niche operators that could offer synergies. Internationally, the key ventures have been JALways and Japan Asia Airways (JAA). JALways was originally launched in 1991 as Japan Air Charter to fly IT charters to popular holiday destinations in the Asia–Pacific region. In 1999 the venture was renamed and transformed into an international scheduled airline that now operates throughout the region, serving destinations as far as Australia and Hawaii and utilising a fleet of 747- 300s and -200s. JAA, originally formed in 1975 to serve Taiwan, has become JAL’s other "Asiabrand" carrier operating 767–300s and 747–300s and -200s.

Domestically, the key new venture has been JAL Express, a low–cost airline–within–an–airline set up in 1998 to operate in secondary markets. The aim was to have unit costs at least 20% below JAL’s through the use of offshore crews with lower salaries, though the cost differential is believed to be closer to 10%. The venture utilises 737–400s and serves numerous domestic cities from its Osaka hub.

On the feeder front, JAL established J–AIR in 1996 to take over the Jetstream 31 operations of JAL Flight Academy; the unit now operates CRJ- 200ERs throughout Japan. JAL also holds majority stakes in several regional carriers, including Hokkaido Air System (1998) and Japan Air Commuter (1983). There is also a 51%-owned subsidiary called Japan Transocean Air (JTA), which was originally established in 1967 as Southwest Air Lines, was renamed in 1993 and has had its fleet upgraded to 737–400s. The Naha, Okinawa–based niche carrier provides service to smaller airports in the Ryukyu Islands.

A cultural struggle

But the event that strengthened JAL the most was its 2002 merger with the third–ranked Japan Air System (JAS). It was the first major realignment in Japan’s airline industry in 30 years — Japan’s version of a post–September 11 industry shakeout. The merger offered only limited cost savings but it made JAL the world’s third largest airline by revenue and gave it a more balanced network. The airline’s domestic/international revenue ratio improved from 2:5 to 1:1, while its international revenues became better geographically balanced, with transpacific accounting for 35%, Europe 20% and Asia 30% of the total. Significantly, the merger closed the domestic market share gap with ANA, creating a duopoly but also setting the stage for new competitive clashes. The JAL/JAS integration under the JAL Group (officially "Japan Airlines Corporation") and common JAL brand was completed in April 2004. Given its strong market position, both domestically and internationally, and minimal exposure to LCCs, one would think that JAL would be a highly profitable airline. The reason it is not has a lot to do with its old–style corporate culture and state–carrier mentality, meaning that it in the past at least it has lacked incentive to adapt to new market realities.

JAL suffers from a range of legacy ills: high labour costs, a less efficient fleet than rivals, uncompetitive route structure, a bureaucratic corporate structure, militant unions and poor morale. The airline was hit hard by demand decline related to September 11 and SARS, because of its international exposure. JAL has also been disproportionately affected by the high fuel prices because of its relatively old and large aircraft.

Then there were the post–2002 safety lapses (mostly in 2005) that prompted customers to switch to ANA and other carriers, particularly in the domestic market. The string of mishaps — from engine fires to metal fragments falling off aircraft — may not have seriously compromised safety and may have been due to bad luck, but they were widely interpreted as a warning sign that the company might be cutting corners in safety as it tries to control costs. JAS merger–related integration issues may also have played a part.

Whatever the reason, the mishaps tarnished JAL’s image. Analysts have suggested that the negative effects may be long–lasting because many of the premium customers who defected have joined ANA’s FFP.

JAL has always suffered from factional rivalry, which has led to frequent management changes and poor employee morale. The airline is heavily unionised and the unions have traditionally wielded much power. In recent years, labour relations have been further strained by the cost cutting and merger–related issues.

JAL’s ability to tap funding from government–affiliated development banks has fostered a sense of management complacency, which has made the airline slow to tackle its problems and respond to changed market conditions. There are now signs, for the first time, that the management is feeling a sense of urgency, but it remains to be seen if the unions' attitudes have changed at all.

The revival plan

Although ANA has historically had the advantage of a stronger domestic network, it is outperforming JAL also because it has shown itself to be more entrepreneurial, leading the way in marketing and projecting a trendier image. It has a more modern culture and better employee relations. It has kept its labour costs in check and has a younger, more fuel–efficient fleet. JAL’s 2007–2010 revival plan aims to "rebuild the group’s business foundation" and achieve sustained profitability. The airline intends to resume dividend payments "in FY2010 or earlier" (a dividend was last paid in 2004, amounting to Y4 per share). Somewhat surprisingly, the business plan assumes no revenue growth in the four–year period, meaning that the profit increase would come entirely from cost reductions. However, JAL hopes to restart growing from 2010, after it has completed the restructuring and when additional airport capacity will be available.

The business plan projects operating revenues of Y2,298bn (US$19.4bn) in 2010/11 — virtually the same as the Y2,268bn estimated for 2006/07. However, passenger and cargo revenues will see some growth in the plan period, while "other" revenues will decline. In 2010/11, international passengers are expected to account for 33%, domestic passengers 32%, cargo 9% and other activities 26% of total revenues. JAL’s earnings projections are equally modest: a gradual improvement in operating profits over the four–year plan period to Y88bn (US$741m) in 2010/11 — still only 3.8% of revenues. Net profit in Year 4 is expected to amount to Y37bn (US$312m) or 1.6% of revenues.

These targets seem modest compared to the 10%-plus operating margins that major European and US carriers strive for. But perhaps a 3.8% operating margin is a reasonable target in a period when revenues stagnate. However, achieving even that margin on a consistent basis may be more challenging.

JAL aims to achieve the business plan goals and financial targets through a range of strategies, including:

- Labour and other cost cuts

- Fleet downsizing and renewal

- Shift to high–profit routes and fleet optimisation

- Expanding low–cost subsidiaries

- Upgrading the premium product

- Focusing on core aviation–related activities

- Reducing debt through the sale of non–core assets.

The airline aims to further improve its safety standards — and it obviously needs to tread carefully with the cost cutting so as not to affect safety. Although this is not part of the business plan (there have been no major safety problems for over a year), it has been reported that JAL will spend US$516m over the next three or four years on improving safety management systems. This will include the largest Line Operation Safety Audit (LOSA) ever performed for a single airline, under which trained personnel from an outside company will board JAL flights to observe flight crew performance for three months, in an attempt to identify the factors underpinning human errors that can affect flight safety.

The cost cutting programme

One thing that is missing from JAL’s revival plan is measures to improve corporate culture and labour relations. Where’s the profit sharing? Performance–related bonuses? (Curiously, the plan mentioned implementing a "large reduction of performance–linked bonus standards".) Where are the improved ways to communicate with employees? JAL’s new cost cutting programme has two key components: reducing labour costs by Y50bn (US$421m) annually and realising a 14% greater efficiency in fuel usage in the plan period. The airline will also review supplier contracts, sales commission rates and work processes, and it will promote e–business.

The labour cost reductions will involve reducing the workforce by 4,300 or 8% by March 2010 (from 53,100 to 48,800). The job cuts will be across the board (including a 10% reduction in head office jobs) and about 80% of them will be achieved through productivity improvements. JAL aims to improve employee productivity by 10% for flight crews, airport/cargo division workers and reservations/ ticketing staff, while sales functions should see a 30% productivity improvement through unified operations within the JAL Group. There will not be any compulsory redundancies; the 4,300 job cuts will be achieved mainly through natural attrition, though a special early retirement programme will play a role initially.

There will be no new wage cuts, but JAL will continue through 2007/08 the 10% across–the board basic wage reduction introduced in April 2006. An overhaul of the pension system will play a major role in achieving the cost–cutting targets. The airline will also review allowances and bonuses.

Significantly, JAL’s top management will share the pain: the new pay cuts for executive directors, effective February 2007, will be around 45% for senior vice presidents and up to 60% for the president/ CEO. Nishimatsu has reportedly set his annual salary at just Y9.6m (US$81,000), which is close to JAL’s average salary and obviously much less than what groups such as the pilots earn.

But it remains to be seen if admirable gestures like that will help win union support for the labour cost cuts. In March JAL’s four main unions were still demanding a uniform Y15,000 (US$126) per person monthly pay rise, though they called off a planned 24–hour strike after talks with the management. JAL has eight labour unions.

Fleet downsizing and renewal

The fuel efficiency measures are expected to lead to operating cost savings of Y18bn and Y8bn (US$152m and US$67m) in 2009/10 and 2010/11, respectively. In addition to fleet renewal and downsizing, the savings will result from measures such as reducing the weight of cabin loaded goods and equipment, engine cleaning, more fuel hedging, a long–term procurement agreement with an oil development and refinery company (AOC Holdings) through equity investment and flight operating procedures that reduce fuel consumption. JAL’s fleet plan calls for the phasing out of larger, older aircraft and bringing in more small and medium–sized aircraft. This means expanding 737 and 777 usage and adding 787s and E170s, while reducing or removing 747s, A300s and MD–80s. The strategy, which is possible thanks to the increase in Haneda slots in late 2009, is intended to cut operating costs by 10% and result in a 1% decline in revenue.

The plan is to bring in 85 new aircraft and retire 64 aircraft in the four–year period. Some of the 747- 400s will be converted to freighters. JAL Group’s total fleet looks likely to increase from 274 aircraft at the end of March 2007 to 295 in four years' time. However, the growth will be in the last two years of the plan. The passenger fleet (260 in March 2007) is slated to decline by one aircraft to 259 in March 2008, then increasing to 263, 272 and 280 aircraft in the subsequent three years.

According to the plan, JAL’s international passenger fleet will grow from 84 to 95 aircraft between 2006/07 and 2010/11. The number of large–size aircraft (747s and 777s) will decline from 49 to 37, or from 58% to 39% of the international passenger fleet total.

In the current financial year, JAL is retiring 10 747 Classics and adding one 777–300ER and three 767–300Fs. The airline has 35 787s on firm order plus 15 options. The original order, for 30 aircraft, was placed in December 2004, and just last month (April) JAL converted five options.

The domestic passenger fleet is expected to grow from 176 to 185 aircraft between 2006/07 and 2010/11. The percentage of medium and small–size aircraft will increase from 90% to 93%. In the current year, JAL is retiring its eight remaining MD–87s and adding more 737–800s, after introducing that type in March. The initial 737–800s are used on domestic routes out of Haneda, but the type will also be utilised on short and mediumhaul international routes, because the fourth runway at Haneda will allow the resumption of scheduled service in such markets. JAL has 30 737NGs on firm order, plus 10 options, for delivery in the next five years.

Network restructuring and product upgrades

Haneda’s expansion was also a key factor behind JAL’s February order for 10 78–seat Embraer 170s, plus five options, for its subsidiary J–AIR. This is a new aircraft type for the JAL Group, whose regional jet operations are currently limited to only nine 50–seat CRJ–200s in J–AIR’s fleet. Network restructuring includes focusing on high–profit routes, right–sizing aircraft in different markets and expanding the lower–cost subsidiaries. The airline forecasts that these strategies, together with product enhancements, will improve domestic yield by 8% and international yield by 2% between 2006/07 and 2010/11. Load factors are expected to rise by three percentage points to 69% domestically and by four points to 72% internationally in the four–year period.

The current summer season is seeing increased frequencies on the high–yield international Tokyo to New York and Paris routes and in the high–growth markets of China, India, Russia and Vietnam. The Tokyo–New Delhi route will switch to subsidiary JALways. Flights will be reduced in weaker markets such as Tokyo–Hong Kong.

JAL has reaped great benefits from its decision, a year ago, to switch from 747s to 777s on its European routes to London, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Paris and Milan. This summer, the airline is down–gauging regionally by introducing the 737- 800 on five routes from Osaka to China and Vietnam. JAL is also boosting its charter flights by 13%, offering destinations such as Alaska, Australia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Mongolia, Palau and the Marshall Islands.

Domestically, the airline says it is building a "business structure that generates stable income" in preparation for the increase in Tokyo slots in 2009. JAL is suspending service on 10 domestic routes and reducing flights on five other routes, while adding one new route (Kobe–Ishigaki) and increasing flights on four routes. With the MD–87s being retired, the domestic market will receive five new 737–800s in 2007/08.

The cargo division is also being prepared for post–2009 growth opportunities. This year JAL is retiring five 747 Classic freighters and introducing three new 767Fs and three newly converted 747- 400BFCs. There will be new freighter service to China and Indonesia and a reduction in flights to the US East Coast.

The main product enhancements will be the introduction of first class on key domestic trunk routes and "premium economy" on international routes. JAL is also improving in–flight meal quality and introducing new seats on all classes in international service.

JAL introduced a new domestic business class, "Class J", in June 2004, which is offered for a small supplement and has been highly popular and contributed significantly to profits. It is now adding a 14–seat first class section in 15 777–200s operated on key trunk routes, becoming the first airline in Japan to offer three classes domestically. The new international "JAL Premium Economy" product will include 40 seats on 777s operated mainly on key Japan–Europe and Japan–US routes.

JAL estimates that the four–year route restructuring will result in the lower–cost international subsidiaries, particularly JALways, increasing their share of the group’s business from 24% (2006/07) to 37% (2010/11). The two main domestic units, JAL Express and J–AIR, will see their share rise from 15% to 26%.

When growth resumes, the focus will be very much on domestic operations, because JAL wants to tip its international/domestic ratio (currently about 50:50) more in favour of domestic operations. JAL’s international operations have suffered much volatility post–September 11, while domestic demand in Japan is very stable. A stronger domestic network will also provide more feed to support international operations.

This contrasts with the current strategies of other global airlines, particularly US carriers, which are focusing on building international services. The starting points are obviously different: most major US and European airlines already have strong domestic/intra–EU operations, whereas JAL has historically been more like Pan Am, Swiss or Sabena, with little domestic feed (all of those airlines failed). And the domestic markets are very different, with the US and (to a lesser extent) intra–EU being highly competitive, while Japan is much less so.

Asset sales are the key

JAL officially joined the oneworld alliance on April 1 after being the only one among world’s top 20 airlines not aligned to a multilateral global alliance. But no–one is expecting much financial impact in the short term — after all, JAL has already cooperated extensively with oneworld members, including American, BA, Cathay Pacific, Iberia, LAN and Qantas. The positive impact is likely to felt in the long term and will include intangible benefits such as bolstering JAL’s image. Another likely benefit is that the joining process forced JAL to bring many of its internal processes and procedures up to scratch — and perhaps enabled it to pick up some good management practices from other world regions — with the help of prestigious "sponsors" like American. When it was privatised 20 years ago, the JAL Group already had 119 subsidiaries and associated companies. After privatisation there was even more diversification, to the extent that the company admitted in 1991 that the process had gotten slightly out of hand and said that it would consolidate. But habits can be hard to break. The latest annual report (for 2005/06) lists a staggering 275 subsidiaries and 97 affiliates. The subsidiaries include 10 airlines; 105 airline–related businesses (handling, catering, maintenance, etc.); 51 travel services companies; 42 finance, credit card or leasing businesses; 24 hotels/resorts; and 43 other companies (trading, wholesaling, retailing, real estate, printing, construction, temp staffing, information, advertising and cultural events).

Under the medium–term business plan, JAL will concentrate its resources on the core air transport business and will restructure non–core activities, selling some subsidiaries and reducing stakes in others. That process got under way this past winter with the sale of two hotels and a trading company. JAL sold its 49% stake in Hotel Nikko Tokyo to US investment fund Aetos Capital, its 57% stake in a hotel in Hokkaido to Meiji Shipping Co, and more than half of its 51.5% holding in airport retailer Jalux to trading house Sojitz Corp.

The hotel deals were not just cash–raising exercises. Now is apparently an opportune time to sell commercial property in Japan, because land prices there rose in 2006 for the first time in 16 years, and there is considerable investor interest and liquidity,helped by tourism recovery and low interest rates. ANA and other Japanese companies are also selling hotels, golf courses and other high–value assets bought in the late 1980s.

JAL raised an estimated Y100bn (US$842m) from asset sales in the fiscal year that ended March 31. The business plan envisages additional hotel and other non–core asset sales bringing in Y51bn (US$430m) in the current year. There are tentative plans to list shares in JAL Hotels Co. in 2008/09.

JAL is fortunate in having significant assets that can be monetised, because it is not in a position to raise equity until its financial recovery is well established. A global public share offering in July 2006 raised a very useful Y140bn (US$1.18bn), but that was 30% less than what had been targeted and the offering stirred up much controversy. Shareholders were unhappy about the dilution (share count went up by 38%) and about JAL’s failure to mention the offering at its annual shareholder meeting two days before the offering was announced. The timing was wrong as JAL’s recovery prospects looked extremely uncertain (it was originally supposed to be a private placement). JAL’s share price plummeted in the weeks before the offering and, in a rare move, one of its underwriters withdrew from the syndicate.

The official reason for the July 2006 share offering was to raise funds for fleet renewal, but in reality JAL needed to bolster its extremely weak cash position — just US$509m, or 3% of annual revenues, in March 2006. The share offering more than tripled the cash reserves to US$1.6bn, but that still amounted to only 9% of 2005 revenues. The norm — and what is generally considered healthy — for global airlines these days is around 20%.

JAL has also needed funds for convertible bond redemptions. At the end of March investors exercised their right to cash in early Y79.7bn (US$671m), or about 80%, of convertible bonds issued in April 2004 that were due to mature in 2011. The fact that investors opted to keep holding 20% of the bonds was a promising sign. JAL has potentially another Y50bn of bonds coming up for redemption this month (May) and another Y20bn in February 2008.

JAL’s fleet is almost entirely encumbered, but the company continues to have access to the unsecured debt market through the government–affiliated Development Bank of Japan (DBJ), whose involvement typically attracts other banks to the syndicate. For the recent bond redemption, JAL obtained loans totalling Y59.5bn (US$501m) from four banks, including the DBJ and Mizuho Corporate Bank in the lead role. The deal was finalised after the banks had scrutinised JAL’s revival plan, and it may be part of a provisionally agreed Y150–200bn (US$1.3–1.7bn) financing. According to the four–year revival plan, JAL will be looking to raise Y98bn (US$825m) in debt financing this year, followed by Y122bn, Y128bn and Y137bn in the subsequent three years.

JAL’s plan anticipates positive operating cash flow of Y137bn (US$1.2bn) this year, rising to Y222bn (US$1.9bn) in 2010/11. The combination of cash generated from operations, new debt financings and this year’s asset sales would more or less cover planned capital expenditures (Y108bn this year and some Y140bn annually thereafter) and debt repayments ranging between Y157bn (US$1.3bn) and Y216bn (US$1.8bn) annually.

The plan aims to reduce JAL Group’s debt and capital lease obligations by 31% in the four–year period, from Y1,455bn (US$12.3bn) in March 2007 to Y1,008bn (US$8.5bn) in March 2011. However, operating lease commitments in that period are expected to increase from Y120bn (US$1bn) to Y275bn (US$2.3bn), meaning that the reduction in total debt and leases would only be 18.5%.

Reducing debt is a prerequisite for the plans to resume growth post–2009, because JAL is highly leveraged, with a lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio of about 91% and net debt/revenue percentage of 90% (as of March 2006) — both much higher than the leverage ratios of other major Asian and European carriers and not far off the US legacy levels.

| Yen (bn) | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 |

| Sources of cash | |||||

| Operating cash flow | 94 | 137 | 165 | 187 | 222 |

| Asset sales | 100 | 51 | 15 | 6 | 4 |

| External financing | 61 | 98 | 122 | 128 | 137 |

| Equity offering | 148 | ||||

| Total cash in-flow | 403 | 286 | 302 | 321 | 363 |

| Planned spending | |||||

| Capex | 139 | 108 | 144 | 141 | 146 |

| Debt repayment | 245 | 186 | 157 | 189 | 216 |

| Total cash out-flow | 384 | 294 | 301 | 330 | 362 |