Air Berlin's IPO: Just bad timing?

May 2006

Air Berlin may be Europe’s third largest LCC and the second largest airline in Germany, but investors were less than enthusiastic about the airline’s May 11 IPO. Was the relative lack of interest merely down to bad timing due to high fuel prices, or was it indicative of serious doubts about the strategy of Air Berlin?

Tegel–based Air Berlin was launched in 1978 as a charter carrier (see Aviation Strategy, December 2004), but today is both a charter and a low cost/low fare airline, with a fleet of 56 aircraft operating 350 flights a day on 135 routes between 18 German and 56 foreign airports, primarily in Mediterranean destinations such as Spain, Greece, Turkey and North Africa. Air Berlin has a staff of around 2,700, including 500 pilots and 1,000 flight attendants.

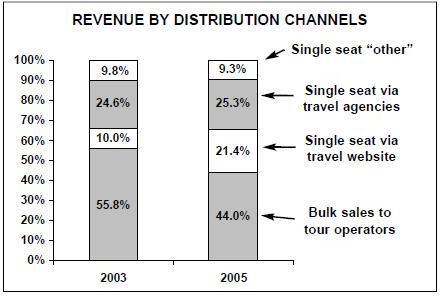

The carrier is a hybrid business of an LCC that focuses on business travellers (with 56% of revenue coming from single seat sales) combined with a charter operation that operates flights on behalf of German tour operators (44% of revenue).

Although the dependence on charter sales is lessening, the volume of business is still substantial, and in 2005 37% of all Air Berlin’s revenue came from bulk sales to just four tour operators — Alltours (13%), TUI (9%), ITS (8%) and Thomas Cook (7%). Air Berlin is still Germany’s leading charter passenger airline in terms of passengers carried (4.7m in 2004), with Condor and Hapag Lloyd in second and third place (3.5m and 3.4m charter passengers respectively in 2004).

However, the structural problem for Air Berlin in the long term is that the European charter market is continuing to decline gradually (with total European charter seats falling at a CAGR of 4% between 2000 and 2004, according to Air Berlin’s IPO prospectus).

The gradual shift in focus, therefore, to non–charter/ seat–only business is logical. This began in 1998 with the Mallorca Shuttle service, which links the island with German cities and whose success led to the formation of the City Shuttle in 2002, which extended seat–only services throughout the rest of Europe. Today Air Berlin operates all city–to–city routes under the low fare brand Euro Shuttle, a name that was formed in 2005 from the combination of the City Shuttle and Mallorca Shuttle brands.

However, Air Berlin’s LCC strategy is slightly different to the standard LCC business model — instead, it places itself "in the upper end of the low fare carrier segment by serving both primary and secondary airports, and by offering passengers extra services at no extra cost". Or, as Joachim Hunold, the CEO of Air Berlin, puts it, it is "a low cost airline with frills".Air Berlin’s LCC operations are also different in that they are based both on point–to–point traffic and (to a lesser extent) on hub–and–spoke operations at Palma de Mallorca, Nuremberg, and — since December 2005 — London Stansted. The Palma hub connects through to 14 Iberian destinations and the airline carried 4.5m passengers to, from or through the airport in 2005.

Air Berlin is now the largest airline at the Balearic airport, accounting for approximately 25% of all passengers carried. At Nuremberg, which connects through to the other airports served in Germany, Air Berlin carried 1.5m passengers in 2005.

The newest hub is London Stansted, which Air Berlin plans to build up fast. In December 2005 Air Berlin began domestic UK flights with routes from London Stansted to Glasgow and Manchester, which it says is in great demand from UK corporates. A service from London Stansted to Belfast was added in May, and according to Air Berlin’s forecasts, 30%-50% of passengers on the UK flights are expected to be travelling point–point, with 50%-70% of passengers being connecting traffic from Germany and other destinations. The hub also serves Berlin, Dusseldorf, Hannover, Leipzig, Munster- Osnabruck, Nuremberg, Paderborn, Vienna and Palma de Mallorca, with Alicante added in May in order to serve the UK second home market.

Further routes from London to Spain are expected.

Air Berlin is targeting 150,000 passengers in its first year of operation on Stansted–Glasgow and 100,000 on Stansted–Manchester, with a break–even load factor of around 70%. If the domestic routes are a success Air Berlin is likely to expand onto other UK airports, although the airline claims that its domestic operations in the UK and Spain are "one–off" businesses, and will not alter the airline’s prime strategy, of European point–to–point routes. On point–to–point, the key origination point is Berlin, accounting for 2m passengers (of which 93% flew to/from Tegel, and 7% to/from Schonefeld), closely followed by Dusseldorf, with 1.8m passengers.

This low–fare, with–frills strategy, based on a network of both point–to–point routes and three hubs, has won Air Berlin has an estimated 8%- 10% market share of the European LCC market in terms of passengers carried, compared with 25–27% for both Ryanair and easyJet. This success led the airline to believe that 2006 was the right time for an IPO. However, the flotation hasn’t turned out as planned.

IPO blues

The IPO has been on the agenda for a while, with the rationale of enabling the original German investors in Air Berlin to make a partial exit as well as raising capital that will allow Air Berlin to expand at a faster pace than previously.

In preparation, in January 2006 Air Berlin changed from being a German limited liability company to a UK public limited company. Not only did this make a listing possible but it also enabled the adoption of different depreciation standards, which in effect "improved" its results in time for the IPO.

The IPO was unveiled in March and, with the assistance of Commerzbank and Morgan Stanley, Air Berlin planned to float on the Frankfurt stock exchange on May 5, with shares representing approximately 75% of the airline’s equity being sold for around €750m-€870m.

Pre–IPO, the airline was held 100% by local investors, including CEO Joachim Hunold (5%), Ringerike GmbH — which holds the shareholding of former Pan Am pilot Kim Lundgren, who founded the airline (26%), Severin and Rudolf Schulte (25% between them), Hans Joachim Knieps (25%), Werner Huehn (15%) and Johannes Zurnieden (4%).

Hunold does not intend to sell his stake until 2008 at the earliest, but the other shareholders planned to dispose of 20m–26.5m shares (with the upper amount being available if the shares were oversubscribed) at a price of between €15- €17.50. Another 23.3m shares were to be offered as part of a capital increase for the airline. The offer period would close on May 4, the final price announced the same day, and trading would begin on May 5.

The IPO prospectus was released on April 19 — for the first time revealing detailed financial data about the airline — and the expectation was that demand would be led by non–German institutional investors keen to buy into a growing LCC.

However, book–building during the investor roadshows was not particularly positive, and in early May it was apparent there was no demand for the shares at the top of the indicative price range, which led to the expectation that the airline would settle on a price of around €16 per share, just beneath the mid–range of the indicative spread of €15-€17.50.

But this judgement was overoptimistic, and the day before the May 5 stock market debut, the "grey market" share price dropped below €14. Although the airline insisted the float would go on as planned, just hours later the IPO was unexpectedly postponed, with the offer period extended until May 10. The reason was simple — the banks couldn’t get the shares away even at the bottom of the price range (€15). On May 5 a new price range was announced — €11.50 to €14.50 — and at the same time the number of shares to be sold was reduced from a maximum of 49.8m down to 42.5m, with 17.4m from existing shareholders, plus another 5.5m under a green–shoe option, and 19.6m for the capital increase (3.7m less shares than under the original plan).

At the very top of the original price range, a successful IPO would have given €464m to the original investors and raised €408m for the airline via the capital increase (before costs in the region of €40m-€60m for bank fees and other expenses).

However, under the adjusted IPO investors would receive a maximum of €332m and Air Berlin would raise no more than €284m if all the shares were sold at €14.50, at the top of the new indicative range.

That’s a long way short of the "minimum" €350m that the airline said it needed to raise from the IPO to fund aircraft purchases (50% of net proceeds), debt repayment (10%), and route expansion and other purposes (40%).

But worse was to come, for demand was still so weak that the shares were sold not towards the top of the revised price range, but towards the bottom — at €12 each (almost one–third lower than the top of the original price range). And on the opening day of trading (May 11), the shares even plunged below €11, before closing at €11.25. The rapid fall from the opening price was described by one analyst as "astonishing", but the downward trend has continued since, and as at May 25, the shares were at €9.93 — a painful sight for those brave investors who bought at €12. Although stock markets in general have softened, Air Berlin’s fall was over twice that of easyJet and Ryanair.

The new shareholding structure is: Free float — 62.1%; Ringerike GmbH — 9.44%; Severin and Rudolf Schulte — 9.08%; Hans Joachim Knieps — 9.08%; Werner Huehn — 5.45%; Joachim Hunold — 3.4%; and Johannes Zurnieden (appointed chairman of its supervisory board once the IPO was completed) — 1.45%.

However, while the €12 price level earned €274.8m for the original investors, it raised just €235.2m for the airline, and after estimated costs of at least €40m, the IPO raised less than €200m for Air Berlin — a substantial €150m less than the "minimum" €350m hoped for/expected at the start of the process.

What went wrong?

While the airline and its advisers are closing ranks and claiming the IPO was a success, the overly optimistic pricing must be embarrassing for Commerzbank and Morgan Stanley, and in particular Ulf Huttmeyer, a former executive at Commerzbank who became CFO at Air Berlin in February 2006.

There has been criticism that existing shareholders were being greedy in the amount they were pocketing compared to what was being raised for the airline. However, in December 2005 the existing investors injected €130m into the airline via a capital increase; the money was loaned to them by Commerzbank, repayable on successful completion of the IPO, this reducing their "profit" on their partial exits.

But putting the issue aside of whether the original investors were greedy or not, why were potential investors less than enthusiastic about the prospects for Air Berlin? Undoubtedly, the timing of the IPO was not ideal, as floating an airline during a period of high fuel prices was always going to be tricky. But Air Berlin didn’t help itself by posting a set of financial results for 2005 that were poor — and poor not only because of rising fuel costs.

While Air Berlin had previously only released revenue data, the prospectus revealed a large operating loss in 2003 (there were still no figures pre–2003), although the airline almost broke even at the operating level in 2004 (see table).

| Operating | |||

| €m | Revenue | result | Net result |

| 2003 | 867 | -52.8 | 36.7 |

| 2004 | 1,047 | -0.7 | -2.9 |

| 2005 | 1,220 | -5.5 | -116 |

But while passengers carried rose 12.5% last year to 13.5m and revenue grew 16.5% in 2005 to €1.2bn, Air Berlin still couldn’t achieve an operating profit last year, posting an operating loss of €5.5m (compared with a €0.7m loss in 2004).

And at the net level, results were even less encouraging, with a net profit of €37m in 2003 dropping to a loss of €3m in 2004 and a substantial net loss of €116m in 2005. Air Berlin blames this on rising fuel prices (Air Berlin originally introduced a fuel surcharge in 2004, raising it for the latest time this May), a net foreign exchange loss of €49.2m and a one–time effect from becoming a public limited company (which cost Air Berlin €59.5m for the "first–time application of the corporate income tax rate").

But, crucially, the 2005 results were less than has previously been forecast by Hunold in March 2005 (when he said the airline was targeting 13.7m passengers carried and a 20% increase in revenue to €1.27bn.

The missing of the target could be put down to rising fuel prices, but while worries about fuel costs have hit the price of both Ryanair and easyJet shares this year, both these airlines have more sophisticated hedging policies than Air Berlin. At Air Berlin, fuel costs rose 39.7% to €240m in 2005, well ahead of the 10.5% rise in ASKs. On average, Air Berlin paid US$1.83 per US gallon of fuel last year, compared with US$1.24 in 2004, but this was partly due to the fact that for some reason Air Berlin hedged less of its fuel needs in 2005 than in 2004. In fact — and very surprisingly — Air Berlin hedged just 5% of its actual fuel usage in 2005, and this lack of foresight/ expertise may have been a concern to prospective investors.

Air Berlin is attempting to correct this oversight and is believed to have hedged at least 85% of its fuel needs for 2006 as at end of May 2006, but it’s a reasonable assumption that many of the contracts signed have been highly priced, since the prospectus states that only 25% of 2006 needs had been hedged as at the end of December, so a lot of hedges have been entered into during the first five months of 2006, when future prices have been high.

The airline is not making an overt profit forecast for 2006, although it "hopes" to return to profit, and according to the roadshow presentation is it is targeting a 20% rise in revenue in 2006, driven by a combination of higher fares, cost–cutting and greater proportion of business travellers.

Commerzbank is more bullish, forecasting net profits of €51m in 2006 (and €86m in 2007), based on increasing revenue per passenger and sustained cost–cutting, the latter to include part of a 38% reduction in food and drink expenses per passenger over the 2005–2008 period (see cost section below).

Some German analysts, however, are not convinced by the Commerzbank figures. One analyst believes that the airline will do well to break even this year, while another — Jurgen Pieper, an analyst with Frankfurt–based Bankhaus Metzler — believes the airline will post a net loss approaching €0.25m in 2006 due largely to higher fuel costs (which he forecasts will rise to 23% of revenue, compared with 19.7% in 2005, 16.6% in 2004 and 15.4% in 2003) and tougher competition. He is also concerned about the long term prospects for the airline, with the airline having to fund high capex due to the substantial amount of aircraft on outstanding order.

Fleet

Air Berlin’s fleet has grown steadily through the 2000s and currently stands at 56, of which 45 are 737s and eight are A320 family aircraft. However, the airline has 55 A320s on firm order and for delivery by 2011 (with six of those being delivered in 2006, 13 in 2007, eight in 2008, nine in 2009, nine in 2010 and 10 in 2011), with another 40 on option, for delivery by 2012.

| Fleet | Orders (options) | |

| 737-400 | 5 | |

| 737-700 | 5 | |

| 737-800 | 35 | (2) |

| A319 | 3 | |

| A320 | 5 | 55 (40) |

| F100 | 3 | |

| Total | 56 | 55 (42) |

An order for 60 737–800s was placed in November 2004 as part of a 70–strong joint deal with Austrian partner Niki, with the first aircraft arriving in September last year. The aircraft in Air Berlin’s chosen configuration (including engines) have a list price of US$65.7m, but Air Berlin won "substantial confidential price and payment term concessions", which may be as high as a 40%-50% reduction on the list price, bringing the actual price down to around $36m.

Currently 31 of Air Berlin’s fleet are on operating leases, including eight from Aviation Capital Group, five from GECAS and four from GATX. On average these leases have just three years to run, so part of the A320 order will be replacement capacity. Air Berlin’s aircraft have an average age of less than six years, and the fleet will expand to 79 aircraft by the end of 2009 as the new 737s arrive.

According to the prospectus, Air Berlin has arranged financing for only 13 or so of the 60 aircraft ordered in November 2004, and the IPO proceeds were needed as the basis for funding of the majority of the rest. How the €150m shortfall in anticipated IPO proceeds will affect fleet financing is hard to quantify at this stage, but if the "lost" flotation proceeds are replaced by commercial borrowing, this will have a financial cost, as well as increasing debt on a balance sheet that already carried long–term liabilities of €478m as at the end of 2005, compared with €433m a year earlier. And whether Air Berlin still plans to pay off approximately €29m of debt (according to the earlier, overoptimistic plan) with the proceeds of the capital increase remains to be seen.

Whatever happens, Air Berlin will remain more leveraged that either Ryanair or easyJet in at least the short–term.

Cost analysis

Being an LCC with frills, the airline inevitably has higher costs than a pure LCC. Those frills are substantial, and Air Berlin’s non–charter flights include free in–flight food and drink, in–flight entertainment, pre–assigned seating and an FFP called Top Bonus. Add to this three types of aircraft, the use of connecting hubs and the serving of both primary and secondary airports (with the former including high–cost Berlin, Dusseldorf and Hamburg), and it’s no surprise that in cost terms Air Berlin is positioned between legacy carriers and the true LCCs.

| €m | % | |

| Airport charges | € 333.4 | 27.2% |

| Fuel | € 239.5 | 19.5% |

| Labour | € 116.9 | 9.5% |

| Navigation charges | € 109.0 | 8.9% |

| Aircraft leasing | € 96.2 | 7.8% |

| Other expenses | € 64.0 | 5.2% |

| Depreciation | € 62.6 | 5.1% |

| Catering | € 48.2 | 3.9% |

| Agent commissions | € 37.2 | 3.0% |

| Technical expenses | € 35.9 | 2.9% |

| Advertising | € 29.2 | 2.4% |

| Other services | € 27.5 | 2.2% |

| Insurance | € 15.6 | 1.3% |

| In-flight material | € 10.3 | 0.8% |

| € 1,225.5 | 100.0% |

Air Berlin’s single biggest cost is airport charges, which totalled more than €333m in 2005, equivalent to 27.2% of all costs. Airport charges rose 18% in 2005, well ahead of the 12% increase in passengers carried, which as Air Berlin admits is "largely due to expansion of the route network to airports in or close to major cities … which tend to have higher airport charges than other airports". Naturally Air Berlin is attempting to cut airport and handling costs — stating that "as our importance at a number of airports continues to grow, we expect to be able to negotiate more favourable terms with both airport operators and ground service providers" — but it is unlikely to achieve any major savings without a switch in emphasis from primary to secondary airports.

More cost cutting is possible in the areas of travel agency commissions (which totalled €37.2m in 2005). In keeping with its hybrid strategy, Air Berlin has a multi–channel distribution channel (see chart), but although web sales are increasing, the airline is actually increasing its dependence on sales via travel agents — which although they provide the majority of single seat sales (most of them being business customers), are an expensive distribution channel.

The non–unionised workforce accounted for just €116.9m — or 19.5% — of total costs in 2005.

Interestingly, becoming a "UK company" now enables Air Berlin to avoid German corporate regulations that requires companies to appoint staff representatives on a supervisory board. This is a continuation of Air Berlin’s aggressive anti–union stance, which previously included organising the airline into small business units, each of which were too small to be regulated by Germany’s union laws.

Relations between pilot union Vereinigung Cockpit (which officially cannot organise at Air Berlin) and Hunold have been strained, and the union claims that the pilots at Air Berlin are unhappy with pay and conditions. VC organised an indicative vote among Air Berlin pilots at the end of 2005, and claims that 94% of the 231 pilots that took part said they wanted a staff representation body. Hunold counters that there is no need for representation among pilots, but sources indicate that one–third of the 500 pilots have "secretly" joined VC, and the union may be close to formally calling for a negotiated pay and conditions agreement with the airline.

Revenue moves

Air Berlin’s two main revenue initiatives for business travellers are:

- Air Berlin Corporate, which allows employees at participating corporate to buy fully–refundable tickets at fixed fares for each of four different "destination zones", with prices fixed irrespective of when the booking is made; and

- YFlex fares, which are fully refundable tickets available to both business and leisure passengers at fixed fares, again irrespective of time of booking.

In addition, many business travellers fly with Air Berlin on standard tickets and fares. Air Berlin aims to win more business passengers by increasing the range of its frills, and in May Air Berlin started to offer "gourmet menus" on flights with meals served on porcelain flights, with a charge of between €10-€20 per meal for passengers who prefer this menu to the free in–flight meal Another key part of the revenue strategy is increasing ancillary revenues — for comparison, at Ryanair ancillaries account for 16% of revenue whereas they total just 2.8% at Air Berlin (and a proportion that has declined since 2003). Part of that difference is due to the sales of in–flight food and drink, which are provided free of charge by Air Berlin. Out of total Air Berlin ancillary sales of €34m in 2005, the three most importance revenue streams were in–flight sales (€15m in revenue), excess baggage (€5.2m) and subsidies from the Spanish government for local flights (€4.6m). Air Berlin plans to increase ancillary revenue per passenger from €2.51 in 2005 to €3.46 in 2008, but it is believed this 38% rise will come largely from the introduction of a fee for bookings via credit card.

Revenue will also come from route expansion, although if the less–than–expected IPO proceeds are going to impact anywhere, it may be on the pace of what is an ambitious route expansion, the speed of which according to some analysts was one of the reasons why potential investors were put off the airline. But if route expansion is affected by a lack of funds, the anticipated "bulk discounts" on airport fees will be harder to achieve.

Air Berlin is looking to expand routes to the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Italian markets, but in particular the airline wants to increase its network to northern and eastern Europe in an effort to reduce its dependence on its main two markets — Germany and Spain — where competition is growing.

Looking eastwards, Air Berlin’s partnership with Austrian LCC Niki (in which it owns 24%), will be important. Together with Niki, Air Berlin is the second largest airline at Vienna airport in terms of passengers carried, and the two airlines believe they have substantial "first–mover" LCC advantage in selected east European markets, which will allow them to pick up a large slice of growing budget and business travel to the region over the next few years. Air Berlin is also expanding operations at its highest cost base — Zurich. Despite (or because of) rivals such as easyJet and SkyEurope withdrawing from Zurich, Air Berlin is planning to base extra aircraft there (it only has one 737 at Zurich at present), with expansion of a route network that currently serves more than 30 destinations across Europe.

While Air Berlin says that "it has no current acquisition plans", increasing competition in the German market may lead to consolidation sooner rather than later. At the end of 2005 Air Berlin agreed an internet partnership with rival LCC DBA, in which each airline’s flights are searchable on the other airline’s web site. The airlines' networks are complementary in that DBA focuses on domestic flights while Air Berlin has a much larger European network, and this initial co–operation is fuelling speculation that closer ties are currently being negotiated, including everything from joint maintenance and ground services to a code–share agreement.

Air Berlin also code–shares with Hapagfly, a charter airline subsidiary of TUI, but a another potential merger or acquisition candidate may be Berlin–based Germania, where in November last year Air Berlin agreed to become responsible for its management after the death of its owner and chairman, Hinrich Bischoff. Germania operates a fleet of more than 40 aircraft, most of which are on wet or dry lease to German airlines such as DBA and Hapag–Lloyd Express, and had been a fierce competitor with Air Berlin through the 1990s until Air Berlin agreed to lease Fokker 100s from its rival and Germania agreed to withdraw from some contentious routes. Hunold and Bischoff then developed a friendship, which led to the wish by Bischoff shortly before his death that Air Berlin took over Germania operations via a management contract; Hunold has since become Germania’s managing director. Germania Express (Gexx), Germania’s former LCC subsidiary, was taken over by fellow LCC DBA in 2005, which raises the intriguing — albeit unlikely — possibility of some kind of three–way tie–up.

The future

Altogether, Air Berlin’s operating cost (excluding fuel) per ASK was 3.78 € cents in 2005, and this figure has risen by 4.1% over the previous two years (the only years that the prospectus gives historical information for), thanks largely to rising airport charges. But add to this the cost of fuel, and Air Berlin’s total cost per ASK for 2005 was 4.70 € cents in 2005, compared with 4.44 €cents in 2004. So although passenger revenue per ASK rose from 4.11 € cents in 2004 to 4.33 € cents in 2005, the negative gap between costs and revenue per ASK increased from 0.33 € cents in 2004 to 0.37 € cents last year.

Although Hunold — who recently signed a five–year management contract — believes there is "significant savings potential", it is unlikely that Air Berlin can really cut costs deeply given its "LCC with frills" strategy". Air Berlin insists that the extra costs of selected frills is more than made up by increased demand from business travellers, but if costs keep rising — or are flat at best — then much depends on Air Berlin’s revenue growth, and in particular in squeezing out of extra ancillary revenue.

The problem is that even if it is successful on ancillaries, core yields are under increasing pressure attack from intensifying competition from German and foreign airlines, both LCC and mainline.

There’s little doubt that fare wars within and to Germany are hotting up, and not only does Air Berlin face increasing competition from Ryanair (which has a major base at Frankfurt Hahn) and easyJet (with a hub at Berlin Schonefeld) — see Aviation Strategy, December 2004 — but also from other German LCCs/budget carriers such as DBA and TUI’s HLX, and German charter companies such as Condor. Perhaps most challenging of all, full service airlines such as Lufthansa and BA are constructing more aggressive strategies against the LCCs, including (but not only) lower fares. Lufthansa also owns 49% of Eurowings, which owns budget carrier Germanwings.

According to Hunold, the airline’s "minimum" goal over the next three years is to maintain its position as the number three European LCC. However, as Air Berlin’s prospectus itself points out, "as growth rates in the LCC segment are generally expected to be lower in the future, this segment is expected to suffer from overcapacity and increased competition … In addition, competition is expected to increase between LCCs and charter and legacy carriers that plan to reduce their cost base and implement low–cost strategies".

| Air Berlin | Ryanair | easyJet | |

| May-11 | 11.25 | 6.81 | 3.58 |

| May-25 | 9.93 | 6.53 | 3.41 |

| Change | -11.7% | -4.1% | -4.7% |