JetBlue: What went wrong?

May 2006

Recent months have witnessed a stunning development on the US aviation scene: JetBlue, the LCC high–flyer with a powerful brand and previously industry–leading profits, is stumbling.

The New York–based airline has posted sizeable losses for the past two quarters and is likely to see one of the worst 2006 loss rates among the solvent US carriers.

Consequently, JetBlue too now has a "Return to Profitability" (RPT) plan. The airline announced the plan in conjunction with its first–quarter results on April 25, and its top executives have discussed the measures further at industry conferences and at the company’s AGM on May 18.

In the first place, JetBlue is slowing growth through fleet reductions — it has deferred 12 A320 deliveries that were previously scheduled for 2007–2009 and is seeking to sell at least two currently operated A320s. Like its legacy counterparts, the airline has identified a hotch–potch of revenue enhancements and cost reductions. But the plan also includes interesting strategy changes, notably a shift away from transcontinental to short and medium–haul markets and major changes to revenue strategy.

JetBlue’s problems are all the more surprising given that much of the rest of the US airline industry is finally seeing light at the end of the tunnel. The best of the lot, US Airways, has even turned profitable, following its Chapter 11 restructuring and merger with America West. So what went wrong at JetBlue? Will the RPT plan succeed in restoring healthy profitability? To what extent will the airline’s business model change?

From best to worst

One industry expert noted at a recent conference that an airline knows that it is growing too rapidly when its returns go to the bottom and it moves from the best to the worst ranking in the DoT’s operational metrics league table. Both of those things have happened at JetBlue.

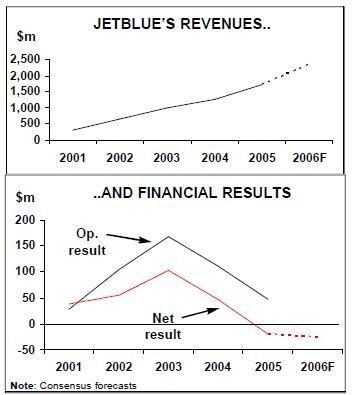

JetBlue’s financial results have deteriorated steadily since early 2004. Its operating margin declined from a spectacular 17% in 2002 and 2003 to 8.8% in 2004 and 2.8% in 2005. Last year saw a $20m net loss on $1.7bn revenues — JetBlue’s first annual loss since it began operations in 2000. 4Q05 and 1Q06 saw net losses of $42m and $32m, respectively. In the latest period, JetBlue trailed the other solvent carriers with a 5.2% negative operating margin.

The losses, of course, reflect a mixture of external/industry developments, over which JetBlue has little or no control, and self–inflicted damage.

Like most other US airlines, and unlike Southwest, JetBlue has not had significant fuel hedges in place. Its average per–gallon fuel price rose from 85 cents at the end of 2003 to $1.86 in 1Q06. And like the legacies, JetBlue has not been able to raise fares sufficiently to compensate for fuel — its average fare has remained unchanged at about $105 in the past two years.

There are several reasons why LCCs have found it harder than the legacies to raise their fares even as the pricing environment has improved. First, they need to maintain a low–fare image. Second, their simple pricing models mean that they have fewer fare buckets to play with.

Third, many LCCs have aggressive expansion plans that require them to focus on filling aircraft rather than pricing for profitability.

JetBlue’s ASMs were up by 27.2% in the first quarter — the fastest growth rate among the US non–regional airlines; yet, its average load factor was an excellent 84.2%. But its unit revenues (RASM) rose by only 3.3% — a far cry from the double–digit increases achieved by the legacies and totally insufficient to compensate for the 16.3% surge in unit costs. 1Q CASM was 7.84 cents, up from 6.84 cents a year earlier, while RASM was 7.46 cents.

Another reason why LCCs have found it hard to raise fares — and this is a very recent development — is that they have lost some of the pricing power that they captured earlier. For example, US Airways actually blocked a fare increase initiated by JetBlue in early May. JP Morgan analyst JamieBaker noted that he could not recall a previous time a legacy blocked a broad increase initiated by a discounter.

Such actions reflect the legacies' superior yield and seat inventory management, as well as a bolder attitude by the carriers that have restructured successfully. Analysts have used phrases such as "tables are turned" and "the revenge of the legacy carriers" to describe this phenomenon. Importantly, though, JetBlue does not have a demand problem. Its traffic (RPMs) rose by 25% and operating revenues by 31% in the first quarter.

But the airline is seeing unfavourable non–fuel cost trends; its ex–fuel CASM was up by 6.7% in the first quarter. Among other things, there were new ground lease payments for the terminal JetBlue has under construction at JFK, higher maintenance costs following the initial "maintenance holiday" associated with the new fleet and tougher than anticipated integration issues with the 100–seat Embraer E190. The aircraft, which entered revenue service in November 2005, had initially poor dispatch reliability, though most of the problems have now been solved.

As an added concern — and a key factor behind the decision to scale back growth, JetBlue’s lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio has again risen to the 75% ceiling imposed by the company.

JetBlue’s credit and debt ratings have seen a steady string of downgrades by rating agencies, which has raised borrowing costs. Most recently, in mid–April Moody’s lowered the corporate debt rating from Ba3 to B2, citing the unexpectedly poor first–quarter results and "long–term challenges to profitability".

All of that has taken a toll on JetBlue’s stock performance. The share price has fallen from a peak of about $30 in late 2003 to the $10 level in recent weeks.

In a mid–April research note, Jamie Baker rather insultingly noted that JetBlue’s actions resembled those of an old–style legacy carrier. "Over–aggressive expansion, unrelenting competition, multiple fleet types, deteriorating operational integrity, earnings disappointment and shareholder value destruction…are we describing JetBlue or United in the late 1990s?" he asked.

However, JetBlue has two great strengths that make it a long–term survivor. First, it continues to be extremely highly rated by customers, as illustrated by a steady stream of "best airline" type awards. As Neeleman noted recently, JetBlue has created true brand loyalty in a commodity business.

Second, with a cash position of $491m at the end of March, representing 29% of 2005 revenues, JetBlue has ample resources to weather a period of losses.

Return to Profitability plan

JetBlue has funded its aggressive expansion, which has seen capacity grow at a compounded annual rate of 54% since 2000, through earnings cash flow, long–term debt and occasional equity offerings. The problem this year has been that, with another $2bn of aircraft funding required in the next two years, the traditional funding sources have either disappeared (earnings) or look difficult (debt or equity issues).

An equity offering is still possible but not desirable as the stock is close to its 52–week low.

Therefore JetBlue was left with basically three options: raising revenues, reducing costs or cutting capital spending.

The airline is having a serious crack at the first two, but there are limits to how much an already–lean low–fare operator can achieve. Therefore aircraft sales and order deferrals seem not just a prudent move but a necessity.

Nevertheless, by "reassessing everything we've ever done" and with the help of five cross functional teams led by senior leadership, JetBlue has identified revenue and cost initiatives that are expected to improve this year’s financial results by $60–80m. Half of the improvements will come from revenues and half from costs. Specific initiatives will be rolled out throughout 2006.

JetBlue’s leadership insists that the airline’s basic franchise is sound. Rather, as Neeleman put it, "we haven’t done a good job in managing our business for fuel prices that are over $2 a gallon, primarily in the way we price our product, schedule our flights and how we control our costs".

A320 sales and deferrals

JetBlue is looking to sell at least two, but up to five if necessary, of the A320s it currently has in revenue service. This is a relatively easy option, given the need to right–size capacity in certain markets and the strength of demand for A320s in other world regions. The aircraft to be sold will be the oldest in the fleet, which will have the added benefit of reducing maintenance costs.

The impact will be to reduce this year’s ASM growth from the previously planned 28–30% to 20–22%. The growth rate will still be high, but at least it will not be the industry’s highest — AirTran, another large East Coast LCC, is planning 24% growth in 2006. JetBlue wants to preserve its ability to take advantage of market opportunities, particularly if the cost and revenue measures are successful.

JetBlue’s deal with Airbus deferred 12 A320 deliveries from 2007–2009 to 2011–2012. The airline will now take five fewer A320s in both 2007 and 2008 (12 instead of 17) and two fewer A320s in 2009. JetBlue opted for more deferrals than sales partly because deferrals were "a sure thing" in light of its relationship with Airbus. However, the airline has taken options for four additional A320s in 2009–2010. At the end of March, its fleet included 88 A320s, with 95 A320s on firm order.

But JetBlue will need to restore profitability to meet the still–substantial A320 funding requirements. Even after the deferrals, aggregate A320 spending commitments as of March 31 were $890m in the rest of 2006, $975m in 2007, $1bn in 2008, $1.15bn in 2009, $1.18bn in 2010 and $1.09bn thereafter.

E190 to play key role

There are no regrets about going for a second aircraft type; to the contrary, JetBlue is extremely pleased with the E190 decision. The E190 delivery schedule remains unchanged as the 100- seater will play a key role in the RTP plan. At the end of March, there were 11 E190s in the fleet, with another 90 on firm order. There are no near term funding issues because the first 30 E190s have committed sale/leaseback financing with GE Capital, covering deliveries through April 2007.

Aside from the dispatch reliability problems, initial market trends have been encouraging.

Customer acceptance has been high, fuel burn better than anticipated and RASM trends extremely strong. By mid–year the E190 utilisation is expected to be in the 11–hour range, which will bring costs to where anticipated. Had the E190s had "normalised" costs in March, they would have already been profitable.

In addition to major markets such as the initial New York–Boston route, the E190 will also be targeted at less competitive medium–density routes that currently have 50–seat or 70–seat regional jet service with high walk–up fares. While JetBlue will offer fares that are substantially below what other carriers are offering, the E190 is expected to have a yield premium over the A320 on comparable stage lengths.

The E190 will also provide feed and develop new markets for future A320 operation. JetBlue has said that it is comfortable with the revised A320 growth rate in part because of the promising E190 market trends in those respects.

Shift to short and medium haul

The RPT plan spells out a shift in flying away from transcontinental to shorter–haul markets. This is in response to higher fuel prices, which are affecting long–haul operations the hardest. There is a need to right–size capacity in certain east–west markets, particularly in off–peak times, and to increase the average fare.

In some way JetBlue is going back to its roots. Its original plan included 44 mainly short and medium haul routes out of JFK. Most of those cities (in the Mid–Atlantic, Midwest, etc.) never materialised as the airline instead focused on developing Northeast–Florida and transcontinental services, which now account for 38% and 47% of its ASMs, respectively (Caribbean accounts for 8%, short–haul 5% and medium–haul 2%).

The east–west services helped JetBlue reduce seasonal variation and gave it industry–leading aircraft utilisation, but due to competition the routes have produced losses in the past couple of years.

Of course, JetBlue has already been refocusing on short and medium–haul markets with the E190s.

The airline still believes that it has an excellent franchise in the transcontinental business, with significant volumes of loyal customers out of Long Beach (its West Coast hub, which is offered as an alternative to crowded Los Angeles) and increasingly also out of Burbank, but that it needs to manage the business differently. With summer transcontinental bookings looking strong, the main capacity pull–down will come in the autumn with the shift of some A320s to short haul routes.

JetBlue executives described the RTP plan changes as "somewhere between a tinkering and a major overhaul". The immediate result will be to change the ratio of long–haul to all other flying, as measured by number of flights, from 1.5 to 1 last summer to 1.2 to 1 this summer.

Since the beginning of this year, JetBlue has added numerous short and medium haul routes, including Boston–Washington, JFK and Boston to Richmond (Virginia), JFK and Boston to Austin (Texas), Boston–Nassau (Bahamas), JFKBermuda, Long Beach–Sacramento, and Orlando to San Juan and Aquadilla (Puerto Rico). Over the next couple of months, the airline will add service from one or both of its Northeast hubs to Portland (Maine), Jacksonville, Pittsburg, Buffalo, Charlotte and Raleigh–Durham, as well as Burbank to Las Vegas. However, JetBlue said that it would remain flexible and responsive to long–haul opportunities, such as the recently introduced Boston–Phoenix and the upcoming Burbank–Orlando routes.

There is no shortage of opportunities. The shift from long haul to short and medium haul will mean the addition of more new cities this year than the 8–10 that JetBlue had previously planned on. As of mid–May, the airline served 36 cities.

New revenue strategies

The most significant changes to JetBlue’s business model will be on the revenue side; in Neeleman’s words, fuel has simply changed the way the airline looks at the world. The premise of the previous model, which worked well when crude oil was at $20–30 a barrel, was to keep costs and prices low and make substantial profits on volume and growth. Now the airline must sacrifice some load factor to the yield.

The key thing, in JetBlue’s analysis, will be to get the system average fare of $105 up by "a few more dollars" — apparently that is all that is needed to cover the increase in fuel prices. Just $110 or $115 would have made a significant difference to the 1Q results.

However, JetBlue does not anticipate changing its low fare structure; rather, it aims to improve the fare mix. For example, in the Florida markets, it needs to sell fewer $69 fares and more $79 and $89 fares.

This means that JetBlue is moving towards conventional yield management and more complexity in its pricing model — strategies that European LCCs like Ryanair have used successfully since their inception.

To emphasise the new focus, JetBlue has moved its revenue management team from Salt Lake City to its New York/Queens headquarters. It also recently hired an experienced revenue manager from US Airways, Rick Zeni, who as VP of revenue management, reporting directly to Neeleman, will oversee the transition.

Neeleman said that there has been a mindset change and that he is optimistic of what the revamped revenue management team can achieve. Also, there is unlikely to be adverse reaction from JetBlue’s loyal customers — many of them have been mailing $5 and $10 bills and checks to the airline to demonstrate that their tickets were unnecessarily cheap.

JetBlue has at least 15 different revenue initiatives under way, including selective capacity cuts, scheduling adjustments to maximise revenue, adjustments to fare buckets to obtain a better fare mix, fine–tuning the overall fare structure (with possible elimination of some of the cheapest fares) and new corporate booking tools.

The airline also hopes to maximise opportunities in the "other revenue" category, including its co–branded credit card and membership rewards programme with American Express and its own online "Getaway" travel package programme.

The latter could grow to a $100m business within a year or two (currently $20m in annual sales).JetBlue is not following the legacy route of charging extra for everything. However, the airline is now imposing its $25 ticket–change fees more stringently. And there are plans to add some amenities to generate more revenues on flights, such as better–quality wine. While LiveTV is seen as part of the "JetBlue experience" and remains free, last year the airline started selling upgraded headsets for a small fee.

Cost reductions

The cost reduction plan focuses on labour efficiency, fuel conservation and more rigorous supply chain management. On the labour front, the aim is to reduce the number of employees per aircraft from the current 93 to perhaps 80. There will be no layoffs, just reduced hiring. JetBlue has also reduced management costs by eliminating or reassigning some jobs and cutting unnecessary perks such as Blackberries.

Surprisingly, JetBlue also believes that it can further reduce aircraft ground time. It hopes to accomplish that by becoming more standardised in the boarding process. The A320s are currently turned around in 30–40 minutes and the E190s in 20–35 minutes.

The growth of E190 operations and the reduction in the average stage length will have the impact of increasing JetBlue’s CASM, but the airline expects RASM improvements to more than compensate for that.

Maintaining culture and brand

While seeking cost reductions, JetBlue is very mindful of the need to maintain and even improve its internal culture and brand equity. This will be even more important as it moves to shorter–haul, more business oriented markets. Among other things, the airline is making its TrueBlue FFP awards easier to redeem and more flexible.

JetBlue also recently reshuffled some top management positions, moving John Owen from CFO’s position to "EVP — supply chain and information technology", a newly created position, and promoting John Harvey from SVP finance/treasurer to CFO. An expert on business technology, Virginia Gambale, has also been brought in as a new board director. The airline said that these strategic changes will help attain the efficiency and productivity aims of the RTP plan.

Future code-sharing?

The mind–set is changing also in respect of code–sharing. Neeleman disclosed at the AGM that the company is open to the idea — and attracted by the revenue potential — of trading customers with other airlines particularly at JFK. There have been preliminary talks with some of the 51 airlines that operate out of Terminal 4, which JetBlue uses for its San Juan flights (otherwise it operates from Terminal 6) on feeding traffic to international services.

The aim is to move quickly, with one or two deals possible "in the not–too–distant future".

JetBlue also sees potential for links with smaller domestic carriers. LCCs have warmed to the idea of code–sharing because the technology is now available to do it relatively easily. At least that has been the experience of Southwest, which has code–shared successfully with ATA for a couple of years and has continued to expand that linkage.

Financial outlook

JetBlue believes that the RTP plan initiatives will lead to operating profits in the second, third and fourth quarters of 2006, culminating in a full–year operating margin of 3–5%, based on a reasonable fuel cost assumption of $2.10 per gallon net of hedges. But a net loss is still expected for 2006 — the current consensus estimate is a loss of 15 cents per share or about $26m. The consensus estimate for 2007 is a net profit of 17 cents per share, though individual analysts' forecasts range from a loss of 20 cents to a profit of 40 cents.

Much will depend on whether JetBlue achieves its relatively ambitious unit revenue targets. The airline expects RASM growth to accelerate from 3% in 1Q to the "low teens" in 2Q, with further improvements in the second half of the year.

Among the analysts who take an optimistic view of JetBlue, Raymond James' Jim Parker suggested in a mid–May research note that Delta’s substantial Northeast–Florida capacity cuts effective May 1, together with JetBlue’s efforts to reinvigorate its revenue management system, will allow the airline to meaningfully improve average fares and RASM.

Parker raised his recommendation on the stock to "outperform", predicting that the RTP plan efforts "will begin shifting investor psychology in a new and positive direction".

At the other extreme, Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg, who has maintained a "sell" rating on the stock, has expressed concern about execution risk and questioned whether the aircraft deferrals and two sales were enough. Linenberg expressed the view that after the initial excitement generated by the RTP plan, "the stock will be range–bound until the company can deliver results".

Former UBS analyst Sam Buttrick (now in the bank’s Fundamental Investment Group) expressed a similar sentiment at a conference in early May. He cautioned that JetBlue may still be taking on too much debt, which, in the event of any adverse development, would give the company less room to manoeuvre.

Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl maintained a "neutral" rating on the stock in mid–May, noting that there is substantial uncertainty as to when JetBlue will return to profitability. In a late–April research note, JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker mentioned the nagging concern in the minds of many investors that JetBlue may have become "just another airline".

In other words, its profitability and growth may simply align with that of the industry and it will no longer maintain a growth stock valuation.