US Majors: "third major shakeout since deregulation"

May 2003

The US airline industry is undergoing what one major airline CEO recently described as the "third major shakeout since deregulation" (the previous ones were in 1982–83 and 1992–93).

This time around, restructuring is in reaction to fundamental changes in the marketplace (the rise of LCCs, Internet bookings, etc) that are very likely to lead to a permanent reduction in revenue yields for the large network carriers.

All of the major airlines have been forced into serious cost–cutting mode since September 11.

But only in the past month or so have we actually seen concrete results on the restructuring front — the type of events or actions that will lead to a more material and permanent reduction in cost levels.

First, US Airways emerged from Chapter 11 on March 31 with lower costs, a strengthened balance sheet and new capital. The airline achieved $1.9bn in aggregate annual cost savings, including $1bn from labour and $500m in reduced aircraft debt and lease expenses. Its domestic stage–length–adjusted unit cost is projected to fall to 10.5 cents per ASM from 12.2 cents in the first half of 2002. It also eliminated $2.8bn of its $8.4bn pre–Chapter 11 aircraft debt and lease obligations. Next, on April 25 American secured final approvals from its unions on wage and benefit concessions that will lead to $1.8bn of annual labour cost savings over five years.

The deals were clinched literally on the courthouse steps as AMR’s board had authorised a Chapter 11 filing in the event that the flight attendants (the last of three unions) did not approve their revised contract that day. Third, right at the end of April the last of United’s unions finally ratified the longer–term concessionary contracts negotiated in Chapter 11 that will enable the airline to cut its labour costs by $2.56bn annually over the next six years.

These developments have significant industry implications. First of all, contrary to earlier speculation (and hopes in many quarters), the industry restructuring process will now not benefit from early Chapter 7 liquidations. This implies that the cost and capacity reductions by the solvent carriers may now have to be sharper.

Second, American has now set the standard for labour cost reductions outside of bankruptcy — a matter of keen interest particularly to airlines like Delta, Northwest and Continental.

Third, American’s cost cuts have illustrated something that the Chapter 11 carriers' actions already suggested, namely that the lion’s share of the cost savings will come from labour. It seems that the biggest chunk of the lease and other aircraft ownership cost reductions at UAL and US Airways (though painful for the lessors and debt holders concerned) came from aircraft that were rejected as part of the downsizing process — something that would not interest the solvent carriers.

But will United’s and American’s cost cuts be enough to set them on a financially sound longer–term footing? What kind of a potential competitive threat do they pose for Delta, Northwest and Continental? And how are the solvent network carriers planning to respond?

United

The earliest that United could emerge from Chapter 11 is mid–2004, though the restructuring process is likely to take longer. There are many important things still to be sorted out, including the business plan.

Nevertheless, securing the labour concessions was a milestone in the restructuring effort.

The new contracts, which took effect on May 1 as earlier temporary pay cuts imposed by the bankruptcy court expired, will help United make the most of the gradual economic recovery and the peak summer season.

In addition to pay reductions, which range between 9% (flight attendants) and 30% (pilots) for the first year, the new contracts provide for what the airline has described as "significant" work–rule changes, as well as reduced pensions and benefits. Significantly, the deals permit a low cost airline subsidiary and substantial expansion of regional jet flying.

The unions released statements to the effect that they recognised the need to take immediate action to ensure United’s survival. Getting consensus agreements should help avoid labour strife, though the unions did not have much choice. Had they not ratified the contracts, United would have simply asked the bankruptcy judge to impose possibly even harsher terms. Getting the concessions was a precondition to continued support from the DIP–lenders.

Otherwise, United is attempting to secure about $500m of annual debt and lease reductions while in Chapter 11 — proportionally less than US Airways achieved.

American

American got the labour cost savings it believes it needs, but that was after weeks of hovering close to Chapter 11 and a corporate drama that showed its leadership in very unflattering light. After already ratifying their concessions between late March and mid–April, the unions were angered by the company’s failure to disclose retention bonuses and pension protections granted to senior executives in 2002 when the voting took place. The issue was resolved after Don Carty resigned as chairman and CEO and the labour deals were sweetened.

The concessions will now run over five years (rather than six) and employees will get better potential bonuses and incentive payments.

Under the new contracts, which became effective on May 1, American’s workers took immediate 16–23% pay cuts and agreed to benefit reductions and work rule changes that will be phased in over time. More than 7,000 jobs are likely to be eliminated as a direct result of the new contracts. In return, employees will get stock options. Of the $1.8bn in savings, wage cuts and benefit reductions account for $1bn and work rule changes $800m. In total, pilots are contributing $600m, flight attendants $340m, TWU–represented workers $620m, and non–union employees and management $180m.

UBS Warburg analyst Sam Buttrick observed in mid–April that, from labour’s point of view, United’s and US Airways' new contracts were clearly worse than American’s. While the deals are similar in terms of block hour pay, American’s are "superior for labour in every other important respect, including work rules, benefits, pensions and profit sharing". (American earlier believed that it would have needed to find $500m of additional annual labour cost savings on top of the $1.8bn to satisfy DIP lenders, had it ended up in Chapter 11.) The labour cost cuts are part of a total of $4bn of annual cost reductions targeted by American.

The company has identified $2bnplus savings from scheduling improvements (the hub de–peaking project), fleet simplification and suchlike.

American is asking suppliers, lessors and private creditors to contribute the balance of up to $200m annual concessions, which is substantially less than US Airways' and United’s debt and lease cost reductions in Chapter 11. American deferred payments on debt due in early April but paid the amounts within grace periods, and it is not expected to try to renegotiate any public debt.

The consensus among analysts is that the $4bn planned savings will significantly improve American’s cost structure and longer–term survival prospects. AMR reported a disastrous $1bn net loss for the first quarter, almost double the year–earlier loss before an accounting charge.

Operating loss for the latest period was $869m, following losses of $2.5bn and $3.3bn in 2001 and 2002 respectively.

S&P’s Philip Baggaley calculated that the cost savings would have reduced AMR’s 2002 pre–tax expenses by 15% (taking into account the fact that last year’s results already included $900m of the $4bn savings). However, even after the cuts are fully implemented, American’s unit costs will still be higher than Continental’s.

In addition to the immediate wage cost reductions, $400–500m of government aid expected in the current quarter and improved cash flow in the summer will help the airline pull through. At the end of April, Blaylock analyst Ray Neidl rated the probability of a Chapter 11 filing by American this year at just 20%, while Merrill Lynch’s Mike Linenberg put it at 50%.

However, liquidity remains constrained and there are potential covenant issues arising at the end of June that, in the worst–case scenario, would require AMR to pay off its fully drawn $834m bank credit facility. In the longer term, there will also be the challenge of dealing with a $22bn burden of debt and leases.

Delta

Of the other large network carriers, Delta is probably under the greatest pressure to take action on the labour front, because its pilot costs are now totally out of line with competitors'. The current contract was negotiated just before the industry crisis in May 2001 and after United’s previous industry–leading deal, with the result that Delta’s pilot pay was previously slightly ahead of United’s and now it is 30% higher than United’s.

Delta responded immediately to the latest developments by presenting proposals to its pilot union to cut hourly wages by 23% and cancel scheduled pay increases this year and in 2004.

The company wanted the pay cuts and various changes in work rules and benefits to take effect immediately (May 1). It is also asking for flexibility to open the entire pilot contract for negotiation in the autumn of 2004 or earlier, depending on its financial condition (the contract becomes amendable in May 2005).

Of course, Delta has been in dialogue with the pilots (its only unionised group) since early February, when it first requested changes to the contract. The pilots rejected the initial request but have since then been co–operative. The union expects to complete its analysis of Delta’s financial information by May 5, and its response to the latest proposals will depend on those findings.

It will be interesting to see how the pilots respond because, unlike American, Delta is nowhere near Chapter 11. CEO Leo Mullin said at the first–quarter earnings call that he was counting on "everyone at Delta appreciating the fact that we are not having this kind of conversation on the edge of bankruptcy". He also made the point that if the issues are not resolved "it will just take us longer to get there".

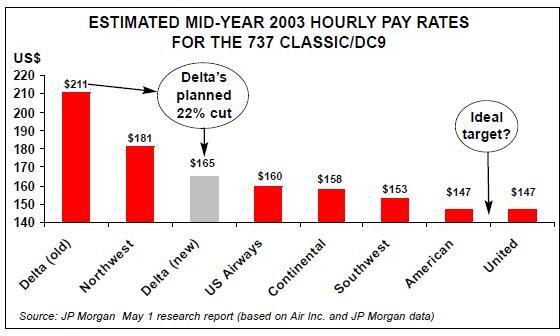

However, in a May 1 research note, JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker suggested that a favourable reaction from the pilots was likely for the simple reason that "it could have and should have been a lot worse". Baker is unimpressed because, by his calculations, the resulting pay rates would still be 12.5% higher than UAL’s and 22% above AMR’s year–one rates. In other words, after also taking into account Northwest’s proposed pay reductions, the cuts at Delta would leave its pilots the highest–paid in the industry. (Baker did note that it was not yet clear if the new deals included significant work–rule improvements.)

Although Delta posted a heavy $466m net loss for the first quarter, representing a higher loss margin than those at Continental and Northwest, its balance sheet is among the strongest in the industry. Cash reserves were an adequate $2.5bn at the end of March — and relatively unchanged from year–end as Delta managed to complete a $350m privately placed EETC in January.

Delta’s cost cutting has so far focused on a broad–based plan to save $1.5–2bn or reduce non–fuel unit costs by 15% by the end of 2005. Low–cost subsidiary Song, which was launched in April and is achieving 22% lower unit costs over mainline 757s, is a key part of the plan. The measures also include continued fleet standardisation and reducing the size of the Dallas hub.

Northwest

Northwest has accomplished impressive cost cuts over the past two years, reflecting the management’s belief that revenues will not recover to historical levels. After the latest cost adjustments by competitors, the airline is determined to secure labour concessions and renegotiate leases and vendor contracts this year.

Northwest is seeking $950m of annual labour cost savings over six years from July 1. Under proposals presented to all seven unions in recent months, the pilots would take a 17.5% pay reduction, mechanics 16.7% and flight attendants9.8%, and there would be benefit reductions across the board. Salaried employees will take 5- 15% cuts in pay and benefits.

In contrast to Delta’s strategy, Northwest has used the threat of Chapter 11 to persuade its unions to take the matter seriously, even though its financial position is as strong as Delta’s — a strategy that may not help labour relations, which have historically been difficult. However, rather confusingly, top Northwest executives have stressed that the company can afford to give the negotiating process time, given its adequate liquidity position. It had an ample $2.34bn in cash at the end of March, including $2.15bn unrestricted cash.

While the initial response from the flight attendants has not been encouraging, Northwest’s pilots have adopted a pragmatic stance. ALPA recently announced its formal aims for the negotiations, namely to ensure Northwest’s long–term viability, sustained future growth, job creation for employees and ability to obtain long–term financing.

The pilots have commissioned independent studies of Northwest’s finances and are working closely with the other employee groups.

Given its relative lack of negotiating leverage, the end result at Northwest will probably be a compromise. Like their counterparts at other airlines, the unions are likely to ask for stock options, meaningful profit sharing and job security.

The company has tried to keep the concessions separate from contract issues, but it may not be possible with the pilots because their contract becomes amendable this September and talks were due to begin in July anyway.

The debacle at American over executive bonuses and pension protection has prompted unions at other airlines to take a close look at such issues before agreeing to concessions. After an unusually stormy annual meeting, Northwest’s CEO Richard Anderson assured employees in a recorded message that the airline’s top executives had not received special perks. In any case, three union representatives sit on Northwest’s board, taking part in discussions about executive compensation and pensions.

Continental

Of the large network carriers, Continental is probably the least threatened by competitors' cost reductions because it already has the lowest unit costs (9.22 cents per ASM in 2002). Although it has closed the gap in terms of pay rates in recent years, it has retained a significant labour productivity advantage over the other large majors.

At the company’s first–quarter earnings conference call, CEO Gordon Bethune said that he had not seen any productivity rates close to Continental’s. He also pointed out that Continental enjoys a unit revenue premium because of its high–quality product and reliability.

Still, Continental must be concerned to see where the new benchmarks will be. Before the AMR and UAL deals were ratified, pilot contract talks at the Houston had been in a 90–day recess "waiting until the smoke clears". Also, in recognition of current industry conditions, a new four–year contract with the mechanics includes a provision to re–open talks regarding wages, pensions and health insurance in January 2004.

In the meantime, Continental has continued to attack costs in other areas. Cost cuts and revenue enhancements implemented since mid- 2002 are expected to improve this year’s pre–tax results by almost $400m. In late March the airline announced a target of $500m additional cost cuts by 2004, of which $100m could be achieved this year. Those savings will mainly come from lower distribution, ticketing and airport costs. The company is also renegotiating contracts with key suppliers and cutting its workforce by another 1,200 positions by year–end.

Over the past 18 months, Continental has consistently reported narrower quarterly losses than the other large network carriers — the latest result was a net loss of $221m in the first quarter, up from a loss of $166m a year earlier. However, because of its relatively weak cash position and lack of credit facilities and unencumbered assets, it could be in a more vulnerable position than, say, Delta or Northwest if industry conditions take a turn for the worse.

At this point Continental is still determined to stick to its fleet renewal plan and resume taking new Boeing aircraft in October, with the help of manufacturer backstop financing if necessary. This is in contrast with other large network carriers, many of which have deferred all new aircraft deliveries until 2005.