Air France: exploiting its asset base

May 2002

Ten years ago Air France was one of the apparent basket–cases in Europe: it was close to bankruptcy, was rescued by the State in a manner that raised the hackles of all the other (non–State owned) European carriers, rescinded the US bilateral to avoid competition, and managed to survive. Now it is taking its rightful place among the top three European carriers, is increasingly focussing on the customer, has formed one of the top three global alliances, and is profitable.

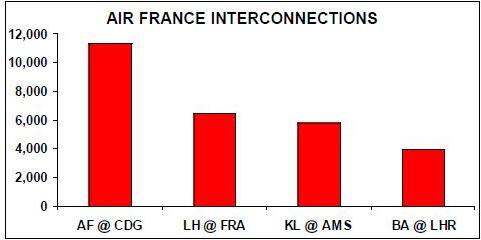

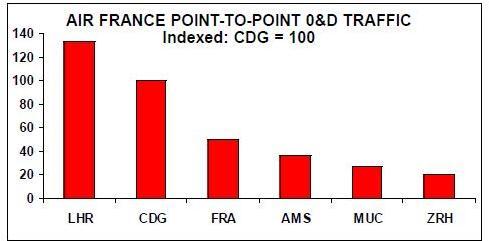

Given that the main asset of any airline is its portfolio of hubs and routes, Air France has an incredibly strong asset base. The top four airports in Europe are London, Paris, Amsterdam and Frankfurt.

Like British Airways at Heathrow and unlike either KLM and Amsterdam or Lufthansa at Frankfurt, it has a strong natural catchment area (the second best in Europe) with 11m people living in the greater Paris area and strong levels of point–to–point O&D demand. Totally unlike BA and similar to KLM and Lufthansa, it has a home base airport at Roissy CDG that has space for expansion, (and importantly the political will to force through that expansion) and the capacity to provide a real hub operation.

The airport’s third runway opened in March 1999 and the fourth in March 2001, with a speed of completion from initial plans that would leave the likes of BAA (the operator of Heathrow) or Fraport (the operator of Frankfurt–am–Main airport) with mouths agape. The interconnection potentials that Air France can provide through its own and its partners' networks now far exceed any other hub in Europe.

In addition, it has at CDG a unique multi–mode hub for passengers and cargo. The airport has its own TGV station and is connected to the TGV network. Air France is able to schedule and ticket efficient transfers between the high–speed train network, for example to and from Brussels or Lille, onto its intercontinental and international air routes. This incidentally provides it with a high level of protection from the incursion of the low–cost carrier.

France has the largest domestic market in Europe (even greater than normal when taking into account the overseas dominions and territories (DOMTOM) in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean and Pacific). France by its very nature and political leanings is highly centralised — and unlike any other European nation maintains the idea that all roads lead to Paris. Air France’s second hub at Paris Orly airport is devoted to the very strong provinces to capital market.

In the mid–1990s, the company took on as advisors Stephen Wolf and Rakesh Gangwal, who have created stockholder value everywhere they have been, except lately at US Airways, to help turn the company around. There are two basic ways to return a company to profitability: cut costs (shrink) or increase revenues (grow). In a heavily unionised government owned airline, cutting staff and shrinking was not an option. In very short shrift they identified that Air France needed to reorient itself. Up to that time, the company was very much an operations- led carrier — it would operate the route structure and schedules to suit the aircraft and the engineers and not the passenger.

Now the concept was inverted and operations and schedules were only to suit what the customer wanted.

As a result the company started turning CDG in to a real hub; established a six–wave pattern to maximise interconnections between long- and short–haul; rescheduled the timetable to maximise user–friendliness (daily flights at the same time each day using the same aircraft). The result was substantial: aircraft utilisation rocketed, staff utilisation dramatically improved, unit revenues increased and profitability arrived.

To get the hub working properly, Air France signed code share deals with both Delta and Continental for its Atlantic services. For both US carriers Air France was a prize — and while Heathrow (Europe’s premier gateway) remains a closed shop for US carriers (neither Delta nor Continental are allowed to fly into Heathrow) Paris with its expansion potential was the next best thing.

After the bilateral air service agreement was torn up in the early 1990s, the company had been operating into the US on an equity basis — and no service expansion had been possible for nine years. As a consequence, Air France had severely lost out to BA, Lufthansa and KLM in the number of flights, frequencies and market share on the world’s busiest long haul route area. In recognition of this, a new bilateral was signed with the US to provide an orderly progression towards open skies between the two countries allowing Air France to build its services over a five year period — and with the opening of the third and fourth runways at CDG, Air France started expanding at double digit growth rates. Because of an element of catch up, combined with the effectiveness of the hub and the links into its partners, it was able to do this and improve unit revenues.

Domestic operations

Following full domestic deregulation in the early 90s, Air France found increased competition not only by other domestic operators by–passing Paris but also by competitors on its trunk routes into Paris. Its strategic response was to concentrate efforts on shuttle services from Orly to the main provincial cities. The majority of the domestic demand in France is direct into Paris.

Because the domestic operations are focussed at Orly, Air France was missing out on feed into its main intercontinental hub at CDG.

It started to franchise smaller operators in the sub–100 seat market to access not only the smaller domestic and hub by–pass routes but also to provide domestic feed to CDG. The advantage here, as the new runways opened at CDG, was that the franchise operators could be treated as new entrants and therefore automatically be granted slots at the airport whereas Air France would have to fight for slots. Once the fourth runway opened it no longer appeared necessary to do this and Air France acquired and consolidated Regional Airlines, Proteus, Flandre Air and BritAir.

The regional network has allowed it to build and operate effectively secondary hubs in France. Regional had originally set up with a hub of operations at Clermont Ferrand — which provides a convenient hub directing traffic through to the South West of Europe. BritAir had started building a hub at Lyons (France’s second largest city) on behalf of Air France — to access intra–European traffic in competition with Crossair’s EuroHub at Basle/Mulhouse.

The high–speed train network (TGV) is both a competitor and a feeder. In terms of elapsed journey time TGV services from Paris to southern cities like Marseilles, Nice and Montpellier are now comparable, and the TGV offers greater comfort. On the other hand, the TGV and Thalys (the high–speed train to Belgium and Holland) has increased the catchment area of CDG. Some 2m airrail passengers are expected this year at CDG.

Employees

Prior to the long–awaited IPO in Feb 1999, Air France negotiated with its heavily unionised workforce to arrange a wages for shares swap. The main deal with the pilots involved a wage freeze and no–strike agreement for an initial three–year period, with a potential for a further freeze in wages for another two years, in return for 15% of the equity. That agreement was based on benchmarked net income rates of pilots with the other major European carriers — and there was an implicit promise to do the same type of benchmarking after the end of the initial three–year period. That has now come to an end — and the pilots recently threatened a four–day strike over the beginning of May.

The top management at Air France are tough — but not as confrontational in labour relations as some. The company reached an interim agreement to raise pilot wages by 1.5% from next year and to start negotiations in earnest in the summer.

Teaming up with others

Because of the problems before its IPO, Air France was late in the global alliance game. It finally plumped for Delta as its North American partner and in June 2000 launched the SkyTeam alliance with Delta, Aeromexico, and Korean Airlines. This move severely upset Swissair (who had had a long standing relationship on the Atlantic with Delta under the soubriquet of the Atlantic Excellence Alliance) and they walked out in disgust to join up with American instead.

CSA Czech airlines joined the alliance in March 2001. Alitalia joined last year following the collapse of its alliance with KLM. The alliance also applied for anti–trust immunity on the Atlantic last year — which was granted in January 2002. They applied in March this year to extend anti–trust immunity on the Pacific with Korean.

The principal hubs of the alliance are very powerful: linking Atlanta, Cincinatti, Paris CDG, Milan Malpensa, Prague and Seoul. Although as always the alliance statistics are somewhat irrelevant for anything but marketing, the group currently offers a combined route network touching some 512 destinations and generates some $40bn in revenues. This puts it on a par with Star and oneworld.

The original application document makes fascinating reading — if only to see the number of ways the lawyers could say "give it to us because you gave it to the others". There is currently no cross shareholding between any of the partners — although there is a rather stupid tentative suggestion for a 5% share swap between Air France and Alitalia, and Delta and Air France have each expressed interest in taking a 15% stake in CSA whenever that carrier may be privatised. Anti–trust immunity will allow them to take the overall level of cooperation to a higher level — including joint inventory management, joint pricing, code share beyond fare incentives and all the trappings of a fully immunised alliance such as enjoyed by KLM/Northwest and Star. The granting of immunity and the signing of a full open skies agreement between France and the US were inextricably linked — and unlike the British attempts to do the same, successful. On a global basis SkyTeam is a small step behind the Star alliance. It currently has only a small number of participants — but this will make it far easier to start the integration process than Star (or oneworld) have found. Air France’s connection with Alitalia is more involved. The two signed a reciprocal agreement last year to operate all flights between Italy and France as code shares, and have full reciprocal agreements on the frequent flier programmes.

They have committed to treat the joint network as a true multi–hub system covering Paris CDG, Milan Malpensa and Rome Fiumicino. This will put Air France in the lead in the multi–hub stakes in Europe and gives it the greatest level of access to the famous "blue banana" of population distribution within Europe.

As always in such alliances substantial synergies are forecast — €180m by 2005 in the Air France/Alitalia case. Most of this will come from network rationalisation, which logically should mean that Alitalia will cut back its loss–making long–hauls and feed Air France’s network at CDG. In practice this strategy will be very difficult to implement.

The two companies are talking about a share swap of up to 5% of capital. This however is fairly meaningless — as all previous alliances in Europe can testify. In time no doubt the two will look to further coordination and potential joint service operations — although while both remain government owned a full merger is impossible.

Recent Results

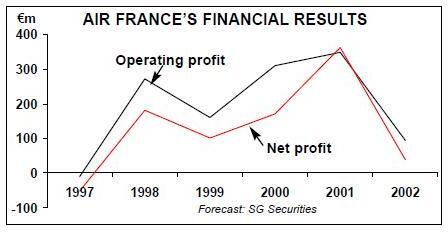

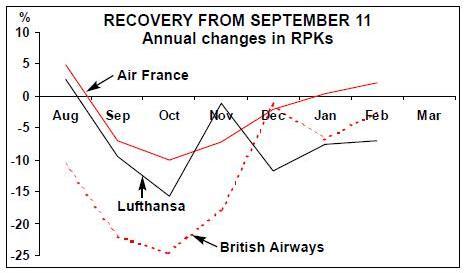

Air France has performed very well since the disaster of September 11. In the quarter ended December 2001, group revenue fell by 7.8% overall compared with same period a year before and underlying cash flow (EBITDAR or earnings before interest tax depreciation and rentals) fell by only 13.6% to €261m. The group posted a net loss for the period of €131m down from a profit of €32m. A large portion of the difference was actually a reflection of differences in the accounting reflection of currency profits and losses on debt and on differences in profits from the sale of aircraft and shares between the two periods. The group estimated that September alone accounted for a loss of €127m.

Air France has achieved a much faster recovery from the events of September 11 than many of its peers. Part of the reason behind this is the relatively low exposure to the Atlantic as a proportion of total operations. Part must be due to the success of its hub connections. Its traffic figures turned positive in January — the first of the European majors to do so — and have continued to improve. The company states that the underlying unit revenues have returned to prior year levels. This gives it the confidence to target "an operating profit" for the financial year ended March 2002.

Outlook

Like the leopard it is becoming, Air France has managed to change its spots. It has the advantage of a strong hub, strong natural demand, and an increasingly powerful European and international alliance. However, there are unresolved issues: the unions remain very powerful, which will make it very difficult for Air France to cut costs and compete with more flexible rivals in a protracted downturn. Its continued success depends on resuming a comparable growth rate to that of 1997–2000.

It is not clear that Air France has a coherent strategy to deal with the low–cost threat. It may be that Air France and Lufthansa are just a couple of years behind BA in experiencing the impact of low–costs on point–to–point city pair traffic and the consequent undermining of network economics. Air France implies that its regional airline network and the existence of the TGV will afford protection, which may be valid domestically but not if, for instance, easyJet succeeds in building a European network from Paris Orly.