How will the manufacturers manage the downturn?

May 2001

A downturn in the manufacturing industry is now inevitable. But, according to an analysis by Deutsche Bank, the main players may be better positioned to weather a downturn this time round. There are three basic reasons for this optimism.

Rising proportion of outsourcing

Over the past few years, both Airbus and Boeing have been actively increasing the proportion of their production that is outsourced. In part this growth in outsourcing is a natural consequence of the rise in risk and revenue sharing across the aerospace industry, in which subcontractors are more deeply involved in aircraft programmes and funding. However, this has also been a deliberate move by the prime contractors to introduce greater flexibility into their manufacturing cost base.

This outsourcing trend is well advanced at Airbus, and growing. In the case of the EADS Airbus operations for example, around 37% of its manufacturing is currently outsourced, and the figure is set to rise further, to around 50% over the next two years as the EADS "make versus buy" policy is further revisited.

For Boeing, increased outsourcing has also been a feature of the company through the 1990s. Excluding the engines, which account for around 25% of aircraft costs, Boeing moved from a 43–45% outsourced mix in the early 1990s to around 50% by 1998.

The traditional company philosophy was to maintain significant in–house capability in many areas in order to ensure stable procurement and avoid losing technical capabilities, which were considered to be core strengths.

This approach changing fundamentally to the view that the company should increasingly focus only on final assembly and a few highly technical value–added jobs. All else seems to be up for grabs.

However, Boeing has also learned that there can be a substantial cost to outsourcing — the production jams its suffered a few years ago were attributed to excessive outsourcing and consequent loss of control over the supply chain. Also, the pace of outsourcing will be moderated by existing contracts with unions.

Reports that Boeing has wooed Japanese partners for wing work on the now–shelved 747X provides some indication that the company will seriously consider going offshore for major elements of new aircraft, especially if this helps the local sales effort. Already, Alenia in Italy is a large supplier of structural components; indeed, according to Airbus, the 717 has less domestic US content than the A318.

Although outsourcing benefits the prime contractors by reducing the fixed cost of their manufacturing base, it cannot reduce the aggregate risk for the aerospace industry as a whole. Since it has to be a zero sum game, risk cannot simply disappear from the system, but will merely be moved around the manufacturing system. More of the pressure during the will shift further down the supply chain.

Reduction in manufacturing lead times

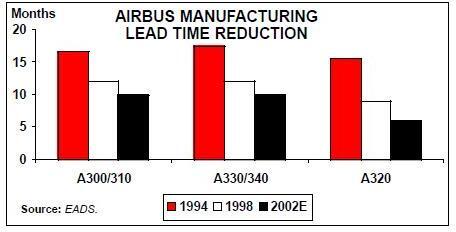

Both Airbus and Boeing have reduced the manufacturing lead times for aircraft. As the table below shows, Airbus’s lead times have already fallen markedly from 1994 for both narrow and wide body aircraft, and are forecast to fall significantly further by 2002.

This should help both the prime contractors and subcontractors in the civil aerospace industry by allowing greater production flexibility to cope with changing market conditions. However, it can never alleviate the underlying problem of overhead under–recovery in what remains a heavily fixed cost manufacturing industry.

Increases in non-OE revenues

Aerospace manufacturers are positioning themselves better to weather a downturn by lowering their dependence on original equipment (OE) revenues through growth in less cyclical aftermarket areas. The aftermarket has traditionally been an area of greater focus for the aerospace subcontractor base, averaging around 30- 40% of civil sales, and a higher proportion of profits because of the higher margins achievable in this sector.

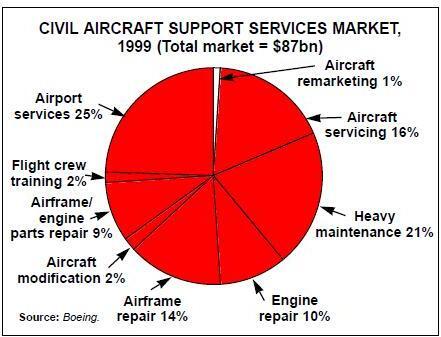

Boeing’s increasing focus on service/support and aircraft conversion (from passenger to freighter) in the past few years is leading to a rise in the group’s non–OE revenues. Deutsche Bank forecasts that by 2004, Boeing’s civil aftermarket service revenues could increase from around $3.2bn in 2000 (10–11% of sales) to as much as $4–5bn (12–15% of sales). Why Boeing is focusing on the aftermarket becomes clear when one considers the magnitude of the opportunity involved, as highlighted by the graph above.

Airbus has placed considerably less focus on aftermarket/service revenues. To some extent, this lesser concentration on aftermarket is inevitable because of the less mature nature of Airbus relative to Boeing. Airbus can still generate significant growth from OE (due to market share gains), whereas Boeing has needed to find other sources of growth outside OE, given its long–term decline in OE market share.