AirTran: reinvented as a high quality low cost carrier

May 2000

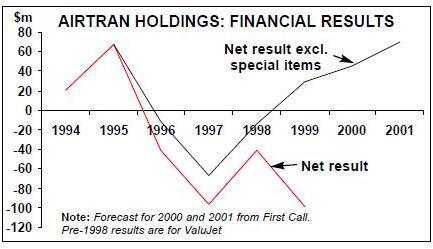

With five consecutive profitable quarters under its belt, AirTran Airways has at last re–established itself as a viable, high–quality low fare carrier — now the largest of the 1990s US start–ups in terms of passenger numbers. It has reported a respectable $2.9m net profit and a 9% operating margin for the quarter ended March 31, following $30m earned before special items in 1999. It is now outperforming much of the rest of the US industry, particularly in terms of unit revenue growth.

The turnaround came after $80m of losses before special charges in 1997–1998 when the carrier, formerly known as ValuJet, rebuilt operations and restructured itself after the 1996 crash and three–month grounding. Under the guidance of former CEO Joseph Corr, ValuJet acquired and merged with AirTran, changed its name and put in place strategies to improve its image. The current CEO Joseph Leonard, who took office in January 1999, has focused on cost controls and refining revenue strategies. Leonard and his management team are very highly regarded by Wall Street analysts.

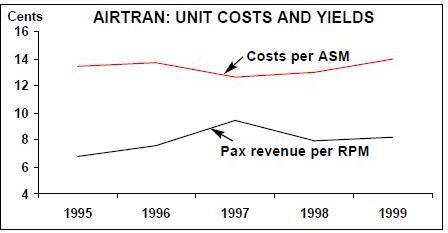

Profitability was restored as unit costs were reduced and yields and load factors recovered substantially. Costs per ASM fell from 9.40 cents in 1997 to 8.19 cents in 1999. Passenger yield improved from 12.60 to 14 cents per RPM in the same period, while the load factor rose by more than ten points.

The unit cost figure may not look impressive compared to ValuJet’s 6.8 cents in 1995, but 8 cents in 1999 was a real achievement given AirTran’s more conventional organisational structure, maintenance and compensation methods and its new focus on the business segment. The level gives it a major competitive advantage — SunTrust Equitable Securities analyst James Parker bravely estimates that Delta’s unit costs at a similar average stage length were about 11 cents.

The 8.6% hike in AirTran’s first–quarter unit costs to 9 cents (due to fuel) looks likely to have been a temporary setback. Ex–fuel unit costs actually fell by 6%. And fleet renewal and other strategies offer good potential for further cost reduction.

While low–fare carriers generally experienced exceptionally strong unit revenue growth last year, AirTran led the pack with a 15% increase. In the March quarter, its revenue per ASM surged by another 11.6%, helped by a 5.3% increase in average fares, which more than compensated for the hike in fuel prices. Although continued double–digit unit revenue growth is unlikely, strong growth is still expected for the summer.

As a result, AirTran’s earnings are expected to surge over the next couple of years. The First Call consensus estimate is a net profit of around $45m for 2000, which would represent a 54% increase. The $70m profit currently projected for 2001 would, for the first time, slightly exceed the record profit earned by ValuJet in 1995.

Little surprise, therefore, that AirTran is now ready to start growing. When announcing the latest earnings mid–April, Leonard indicated that capacity growth will accelerate towards a 15% annual rate in the second half of this year and stay at that level for the foreseeable future.

Previously the company had envisaged more moderate 7–10% annual growth over the next couple of years, after virtually no overall ASM increase in 1999. But the 717 programme, which includes 50 firm deliveries by the end of 2002 plus 50 options, can obviously accommodate faster expansion, even though the aircraft was essentially meant for replacement purposes. Much of the growth is in the options, which do not have to be confirmed until early next year.

Despite the expectations of sharply higher earnings and a low current valuation, four of the seven analysts covering AirTran continue to rate it as a "hold" and only two recommend it as a "strong buy". And even the most bullish of the analysts, James Parker, considers the shares only "appropriate for aggressive accounts".

There are two main risk factors. First, AirTran’s presence on the East Coast exposes it to intense competition from much larger and financially stronger carriers. In particular, Delta is an ever–present threat at Atlanta, where AirTran produces 93% of its ASMs.

Second, AirTran faces a massive $230m debt payment in April 2001, which it will need to restructure. That should be possible but acceptable terms cannot be guaranteed. The airline is looking into the possibility of a private or public placement. Even if all goes well, the refinancing is expected to be at a much higher interest rate than the current average of 10.35%. This and the additional 717 financings will add to interest costs.

AirTran’s balance sheet has already been weakened by a string of substantial restructuring charges — related to ValuJet’s shutdown, rebranding and accelerated aircraft retirements — that led to net losses in each of the past four years. Most recently, a $148m non–cash pretax charge related to DC–9 retirements resulted in the company reporting a $99m net loss for 1999.

Long–term debt surged from $88m in 1995 to $396m at the end of 1999, while total assets rose from $347m to $467m. The latest fleet disposition charge gave the company a negative net worth of $40m at the end of 1999, compared to stockholders' equity of $162m in 1995.

The only bright spot on the balance sheet is the recent dramatic improvement in cash position. After steadily dwindling from $254m in April 1996 (the month before the crash) to just $24.4m at the end of 1998, unrestricted cash rose to $76.2m at the end of last year. (AirTran was very fortunate in having so much cash to start with.)

Benefits of 717 introduction

But in order to secure the refinancings, AirTran will need to continue building up its cash reserves. Its future seems rather critically dependent on the continuation of a favourable economic and fare environment this year (which seems likely) and on attaining its cost and revenue targets. Not so long ago, the massive 717 orderbook, which dates from the pre–1996 days, seemed extravagant for a struggling low fare carrier, but now that brand new aircraft are becoming a norm for new entrants everywhere and AirTran has become profitable, the strategy seems unbeatable.

AirTran may have paid as little as $20m per aircraft, for which it was the launch customer (the current list price is $33m). It got a major say in the design specifications. The aircraft is ideally suited to its short haul, high–frequency markets. AirTran operates it in 117–seat, two–class configuration, gaining a useful 11 extra seats or 8% more capacity over the DC–9.

But, most significantly, the 717 offers a major reduction in maintenance and fuel costs and improved operational reliability over the late 1960s and early 1970s–vintage DC–9s. Those benefits are expected to more than compensate for the higher ownership costs, leading to a net reduction in overall costs per ASM. The DC–9s and the 737s are due to be phased out by the end of 2003.

Initial experience with the 717, which was introduced in October, has been good, with only "some normal new aircraft glitches". Fuel performance is exceeding expectations — a 24% improvement over the old aircraft.

Although the fleet renewal programme has only just got under way, there are some immediate major cost savings. First, the late 1999 DC–9 write–down has reduced depreciation costs by about $24m annually. Second, ten of the oldest aircraft were retired at the end of 1999, which could lead to a similar saving in maintenance costs. Third, as the structural life improvement programme and Stage 3 modifications on the DC–9s are wrapped up by the summer, maintenance costs will fall. Fourth, there are fewer Cchecks this year and engine reliability has improved.

Distribution, fuel and labour costs

The ten 717s already in the fleet were financed through a $178.8m private placement of enhanced equipment pass–through certificates (EETCs) in November. Two of those aircraft were recently sold and leased back under a leveraged lease agreement. EETCs are likely to be the preferred method also for the future 717 financings, which Boeing has guaranteed. AirTran is already an industry leader in Internet bookings. After expanding its own web site, which has won awards for user–friendliness, the carrier raised its total online bookings from 8% at the end of 1998 to around 17% of passenger revenue last autumn — way above competitors' levels. Savings in distribution costs have been substantial as an Internet booking costs about 30 cents, compared to $9.50 if made through travel agents.

It is hard to predict how much higher the Internet percentage can rise — the airline says that the volume is now again picking up. But a recent reduction in the travel agency commission rate from 8% to 5% will lead to distribution cost savings this year.

After being extremely well hedged for fuel last year, AirTran entered 2000 with a hedge covering only 11% of its fuel requirements. As a result, the price it paid for fuel more than doubled in the first quarter. In late March a new agreement was signed covering about 15% of fuel consumption through September 2004 at a rate below $22 per barrel.

Judging by the 16.4% increase in labour costs in the first quarter, AirTran remains under pressure on that front. The hike was attributed to contractual and seniority pay increases last year, increased block hours and more pilots moving to the 717 training programme. New contracts signed in recent years have included competitive wages and annual pay increases.

Contracts with the pilots and the mechanics become amendable in March and August 2001 respectively. Talks with the dispatchers, which joined TWU last year, are under way for a first contract. But, on the bright side, customer service, ramp and reservation agents recently overwhelmingly rejected an IAM vote.

Yield prospects

The biggest labour issue seems to be staff turnover as AirTran’s wages, which it describes as "slightly higher than market for most categories", are extremely low compared to those of the major carriers. The airline loses about 15% of its pilots each year but "stays well ahead of it". Only ramp workers and agents have an unacceptably high turnover. The solution has been to move two thirds of reservations to Savannah (Georgia), where the company is apparently a desired employer. AirTran has staged an amazing transformation from a "penny–pinching" operator into an up–market carrier with an enhanced quality image. Its attractively–priced "no–frills" business class and innovative "A–Plus Rewards" FFP have been instrumental in pulling in higher–yield traffic.

The business passenger component (defined as those booking within seven days of travel) has increased steadily to account for 42–43% of total traffic and almost 60% of revenues. In the March quarter, the average load factor in business class was almost 60%, compared to 30% a year earlier.

Business mix, yields and load factors should continue to improve as the 717s replace the older aircraft in more markets. A new yield management system, expected to be in place by mid–summer, will have a major positive impact as the airline currently has no such system. The management estimates that the revenue–boosting impact could be as much as $30m annually.

Growth strategy and competitive risk

Economic conditions and the pricing environment have been so strong that AirTran, like some other low–fare carriers, has initiated several fare increases in the past six months (which the major carriers have obviously very happily matched). AirTran has established a very successful hubbing operation at Atlanta, which has a large local traffic base and is ideally located for attracting connecting passengers. Local traffic growth there has averaged 10% annually since the early 1990s, compared to 4% nationally.

The markets served are generally within 1,000 miles of Atlanta and include all the key business centres in the Northeast, as well as Chicago, Houston and Dallas, and various leisure markets in Florida. Frequencies range from two to 15 per day.

While key business markets like LaGuardia have been successful, the initial strategy of operating some nonstop flights between Orlando and the Northeast was scrapped in 1998. Over the past year, the connecting component at Atlanta has grown from 55% to 60% of total traffic.

But AirTran is now again ready to experiment with nonstop flights that bypass Atlanta. It recently linked Philadelphia with Orlando and Fort Lauderdale and is pleased with the initial results. In June it will start serving Minneapolis as an extension of its Chicago (Midway) flights. The strategy is described as "some kind of diversification, on a gradual basis".

Analysts like James Parker believe that, while Delta poses a risk, the two can co–exist in Atlanta. In a February report, he suggested that this would be because of AirTran’s lower costs and modest capacity expansion, increased scrutiny by the regulators and business traveller resistance to the major carriers' high fares. Indeed, Frontier appears to have survived competition with United in Denver for those very reasons.

But since then AirTran has announced its intention to ramp up capacity growth to 15%, which would be twice as high as the 7% annual local traffic growth projected for the Atlanta markets over the next few years.

Some of the expansion will obviously be in markets that Delta would not want to serve anyway. Joe Leonard said that "with our cost structure, there are lots of places we can put our aircraft where our competitors cannot". But since AirTran is unlikely to abandon its focus on business–oriented markets, fierce competitive clashes with Delta seem inevitable.

| Total assets | Long-term | Shareholders | |

| debt | funds | ||

| 1995 | 347 | 88 | 162 |

| 1996 | 417 | 193 | 123 |

| 1997 | 434 | 241 | 94 |

| 1998 | 376 | 237 | 56 |

| 1999 | 467 | 396 | (40) |

| Current | Orders Remarks | ||

| fleet | (options) | ||

| DC-9-30 | 35 | 0 | 10 to be retired in 2001, 15 in |

| 2002 and 10 in 2003 | |||

| 737-200 | 4 | 0 | 3 to be retired in 2001 and 1 in 2003 |

| 717-200 | 10 | 40(50) | 6 more in 2000, 16 in 2001 and 18 in 2002 |

| Total | 49 | 40(50) | |