Lufthansa: not just an airline but a true aviation company

May 2000

Over the past few years Lufthansa has established itself as the leading Euromajor in terms of size, profitability and alliance development. It has achieved a complete turn–around from the early 90s when it was, for a while, Europe’s most unprofitable airline, and now aims to evolve from an airline into a true aviation group.

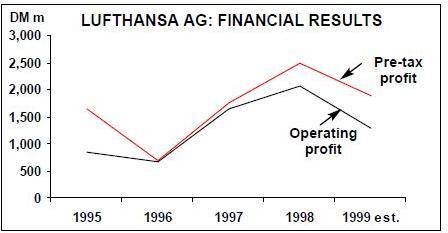

Yet Lufthansa’s success is relative: the airline has been flattered by comparisons with BA whose star has waned so badly in recent years. For 1999 Lufthansa is expected to report operating profits in the order of Dm1.3bn ($600m), but this represents just half of the 1998 result, Dm2.48bn, and is also well below the Dm1.65bn reported in 1997. Pre–tax profits will be around the Dm1.9bn ($880)mark, boosted by income from the stock–market listing of Amadeus. Final results will be published on May 4.

Lufthansa has gone for growth, adding capacity at a faster rate than almost all the other Euro–majors. In 1999 total ASKs were increased by 13.7% with most of the increase concentrated on long–haul routes. Capacity on Atlantic routes surged by 19.7% while intra–European growth was kept to 7.2%.

Remarkably, the increase in RPKs almost equalled that of ASKs will the result that the passenger load factor was down only marginally, from 72.9% to 72.6%.

This, however, has been at the expense of yields, which in the first nine months of 1999 fell by 9.5% on average. Yield trends on the North Atlantic were particularly alarming — a decline of over 12% was recorded in the first nine months of 1999. With this rate of capacity growth a decline in unit costs is inevitable, but they only fell by an estimated 5% — hence the halving in operating profit.

This year Lufthansa is moderating its capacity growth to around 7% but that is still above the forecast AEA average of 4.5% and among the Euro–majors is only exceed ed by Air France. However, most of the growth in 2000 will be concentrated on the rapidly recovering Asia/Pacific routes while North Atlantic increases will be restrained to 4–5%.

Although Lufthansa faces growing capacity constraints at Frankfurt, it is able to alleviate this problem by diversifying to other German cities. The German market is geographically dispersed into medium sized conglomerations, enabling Lufthansa to build secondary hubs at Munich, Berlin and Leipzig, all of which are new airports. As the EU expands eastwards through the inclusion of former Soviet Block states, so the value of Lufthansa’s hubs will be enhanced. Frankfurt itself is now likely to be allowed to expand after a mediation process involving Lufthansa, local industry and environmentalists.

Lufthansa’s strategy is in some ways the opposite of BA’s although they both rely on the same market for their profitability — the long haul business traveller. Lufthansa’s ability to offer an increasing number of connections has undoubtedly won business from BA, but Lufthansa also competes on price. According to a survey by American Express, a UK based company can expect to pay 76% more for 200 business–class trips to New York than its German equivalent.

The strength of the Euro accounts for a large part of this advantage. Since Germany tied its currency to the Euro in early 1999, the common currency has fallen by almost 25% against sterling and the dollar.

A recovery in the Euro is one of the threats facing Lufthansa. This development could erode some of the airline’s pricing advantage as well as undermining its cost competitiveness. Ironically, a recovery is possible because of the increasing strength of the European peripheral economies and convergence between the three main continental economies — Germany France and Italy.

Lufthansa appears to have overcome or at least suppressed the inherent cost disadvantage of operating from a country noted for efficiency but where high wages and inflexible practices are the norm. The company has tackled labour costs through pay freezes and hiring freezes rather than large scale redundancies. As as result it has not experienced the same degree of industrial discontent as BA, and it has been able to incentivise the staff through profit–related bonuses. Its Program 15 launched in June 1996 with the aim of cutting costs to 15 pfennigs per passenger–kilometre reached its target by the end of 1999, two years ahead of schedule.

The aviation group concept

But again there are concerns about whether apparent efficiency improvements at Lufthansa (and in the rest of German economy) are simply the result of a temporary export boom generated by currency depreciation. Lufthansa has in the recent past complained about the problems that a very strong Deutschemark has caused. Now, operating with a very soft currency, it managed to achieve double digit traffic growth last year while German GDP grew by a mere 1.4%. A key element of Lufthansa’s turn–around in the mid 90s was the airline into separate business units each with its own profit targets and each encouraged to trade resources with other members of the group. Since 1998 this strategy has been evolving further — as Jurgen Weber puts it, "from being an airline group to an aviation group offering a range of air transport services in seven fields of business — passenger airline [Lufthansa and Cityline], logistics [Lufthansa Cargo], maintenance and overhaul [MRO], ground handling [Globeground], catering [LSC], IT services [Lufthansa Systems and Amadeus], and leisure travel [C&N].

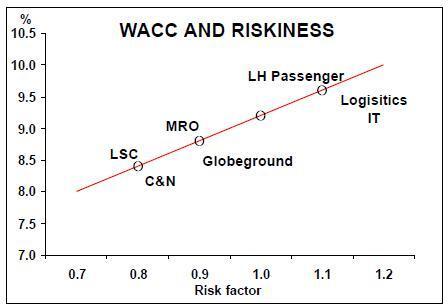

Each of these segments has different characteristics in terms of maturity, potential riskiness and profitability. The graph above illustrates how Lufthansa has analysed the riskiness of each segment against the weighted average cost of capital employed by each segment. The next step for Lufthansa is to define target rates of return for the segments.

By having this range of services Lufthansa aims to reduce its exposure to the cyclicality of the airline business. In the longer term, for instance, Lufthansa will be looking for major returns from its IT operation where it is trying to set itself up as a European rival to Sabre Technologies. It has also set up an autonomous subsidiary, Lufthansa E–commerce, with the intention of creating a new virtual travel agency and "Infogate" which will sell Lufthansa services through integration with other websites.

The strategy also means that the company has a portfolio of assets that it can trade to raise cash for purchases or simply to crystallise value. Lufthansa is a bit sensitive about asset sales, having reacted angrily to reports in the Frankfurt edition of the Financial Times that it would have to sell off subsidiaries to meet its 2000 profit projections.

Without asset sales Lufthansa could see the strength of its balance sheet weakened. According to an analysis by Goldman Sachs in February, capital expenditure in 2000 is expected to be Dm 4.5bn in 2000, up from Dm4bn in 1999. But this year the group is only expected to generate cashflow of Dm2.6bn, which means that after several years of free cashflow generation net debt will rise again — to about Dm 4.8bn by the end of 2000.

LSC, the catering unit, will probably be spun off in an IPO next year and Lufthansa Cargo will also floated in some form. In April Lufthansa entered into a strategic alliance with Deutsche Post, which involves the establishment of a company, called Aerologic, to coordinate their interests in DHL (Lufthansa and Deutsche Post both own 25% of the integrator).

Ultimately, a more ambitious project is envisaged, in effect a merger that would bring together Lufthansa Cargo, DHL and Danzas (Deutsche Post’s airfreight subsidiary). The idea is to create an integrated express freight/air cargo operation, which would offer the opportunity of rationalising costs, improving the utilisation of the Lufthansa Cargo fleet and broadening market power. Lufthansa has suggested that this merger has just been postponed to 2001 for tax–related reasons

In the charter/inclusive tour sector C&N Touistic, which is 50% owned by Lufthansa and 50% by the retailer Karstadt Quelle, is bidding for Thomson/Britannia. This would create a third major force in the European tour operating business alongside Pressag/TUI and Airtours. It would also open up the possibility of reducing the cost of charter flying operations from German towards British levels. But Thomson’s management has so far rejected the bid of £1.45bn ($2.4bn) on the grounds that its current share price (which has halved since flotation in early 1998) greatly undervalues the potential of the company. There are signs that Thomson is becoming less hostile to C&N, and the deal may still go through.

Although Star is in some ways a very democratic alliance — with the various committees and working groups set up to oversee interlining, marketing, cargo, etc being headed by representatives from all the member airlines — Lufthansa is the driving force behind the alliance. Its commitment to Star is total whereas United’s strategy briefings to analysts scarcely mention Star, and Singapore Airlines has its own agenda and global ambitions (Briefing, February 2000).

It is Lufthansa’s intention to extend the aviation group concept to the whole Star alliance. This would involve, for example, the formation of an IT unit for the 14 airlines, a joint purchasing company for supplies, parts and ultimately aircraft. It is likely that Star will soon hire its own employees in addition to those seconded from the member airlines.

This policy is evolving through a series of joint ventures among the Star airlines and other companies. For example, Lufthansa has pressed ahead with a "New Global Cargo Agreement" with SIA and SAS which "will offer a portfolio of harmonised air cargo products, synchronised sales and customer service activities”. The aim for all the Star members is that all the main cargo centres will be shared within the next ten years.

Probably the biggest challenge now for Lufthansa is to increase the synergistic benefits of the Star alliance in the mainstream passenger business. A joint venture could be developed by around British Midland’s route network and would also include SAS. The concept, as Aviation Strategy understands it, will involve combining or pooling the assets of British Midland (excluding the British Midland commuter division), the SAS assets used on Scandinavian–UK routes and the Lufthansa assets used on Germany–UK routes.

Route rationalisation will be important — British Midland has announced that it will be dropping its six daily flights on Heathrow- Frankfurt, leaving this for Lufthansa, and has also terminated its services to Warsaw and Prague. British Midland may then operate the thinner German and Scandinavian routes on behalf of the other Star airlines, exploiting its lower cost structure.

SAS had for many years been frustrated by the lack of progress it has made with British Midland, but now it has sold half its 40% shareholding to Lufthansa, this appears to be a catalyst for change. British Midland’s decision to join Star is also a signal of commitment which means that both SAS and Lufthansa can now drive some value out of their cross–shareholding in British Midland.

One area of saving that joint venturing can have is in terms of management headcount. It is assumed that the joint venture would have one management team, one sales force etc. Subject to any regulatory restrictions one management team rather than a committee (with representatives from three different airlines) could then make decisions on fares, capacity, and scheduling. One hurdle to such an arrangement is overcoming objections from the unions.

Dominance and networks

Having once rejected the idea of equity stakes as a means of cementing Star, Lufthansa has evidently revised its opinion. It has been willing to inject capital when it sees a part of Star under–performing or under threat from a rival alliance. It made a major contribution to the $600m rescue capital for Air Canada, along with United and a financial consortium, to prevent Onex/American getting control. It seems willing to participate in the Thai privatisation, presumably along with other Star airlines. It intends to buy out SAir’s 10% of Austrian, and it will probably be a trade investor in Malev. Could Varig also attract much needed funding from Lufthansa? Lufthansa’s aim is to dominate all the markets it is in. As a network carrier it regards scales in the same way as a telecoms company — each new Star member or each new route creates a huge number of potential new connections. But when does this strategy risks provoking a reaction from the anti–trust authorities. Indeed, a more aggressive body than the Kartelampt might have questioned more thoroughly Lufthansa’s dominance of the German domestic market and its reactions to new entrants. (In fact, Go has complained to the EC about Lufthansa forcing it off the Stansted–Munich route by matching capacity, frequencies and fares until Go was forced to retreat.)

Lufthansa’s position is that its strategy is essentially consumer–led, that if flyers don’t appreciate the benefits of an alliance then that alliance will fail. Inter–airline competition on long haul routes has evolved into inter–alliance competition, with each alliance each battling to route passengers over its own hubs.

Lufthansa believes that the regulatory authorities have not appreciated the global changes that have taken place. Jurgen Weber has called for a single competition authority with global jurisdiction, which seems a bit ambitious at the moment. Still, the TCAA may provide an opportunity for the US and EU to harmonise their competition rules.

Occasionally, unguarded remarks from Lufthansa executive raise eyebrows, as the strategy seems to entail a good deal of old–fashioned collusion. For example, Karl- Friedrich Rausch, the COO, was recently quoted in Singapore as describing the working in Star in these terms:

``It won’t be the survival of the fittest … Let’s say we are sharing costs and revenues on particular routes. So, we have the same fares; we have just one sales force…On some routes, one partner has a better outcome from the cooperation than the other partner.. .But in the end, if both have profits, it’s a win–win situation, a multiple–win situation".

With regard to the regulators, Star may become a victim of its own success. There isn’t as yet a number of global alliances competing vigorously; there is Star, the first in the game and by far the most coherent, and three others which are either stumbling to find an identity or are self–destructing.

| Current | Orders | Remarks | |

| fleet | (options) | ||

| 737 | 77 | 0 | |

| 747 | 44 | 4 | |

| A300-600 | 13 | 0 | |

| A310 | 5 | 0 | |

| A319 | 20 | 0 | |

| A320 | 33 | 3 | |

| A321 | 22 | 4 | |

| A340 | 24 | 24(6) | Delivery 2000-2004 |

| MD-11F | 9 | 5 | |

| BAe146 | 18 | 0 | |

| CRJ | 35 | 19(10) | Delivery 2000-2002 |

| 728JET | 0 | 60(60) | Delivery 2000-2006 |

| Total | 300 | 119(76) |