Midwest Express: unusual formula, consistent success

May 1999

Midwest Express is unique among the US post–deregulation new entrants in that it survived and has been consistently profitable. This is because it went against the grain: providing superior service at reasonable prices, catering primarily to business travellers and adopting a cautious, low–risk growth strategy. But can profit gains be sustained in the face of more intense competition and labour cost pressures?

About to celebrate the 15th anniversary of its first flight on June 11, Midwest Express was founded in 1984 as a subsidiary of K–C Aviation, which is part of the Kimberly–Clark Corporation. The industrial conglomerate had been providing air transportation for its own executives between headquarters and company mills since as early as 1948, and deregulation enabled the Kimberly–Clark Corporation to capitalise on its aviation expertise through the formation of a commercial airline venture.

The corporate aviation roots meant a natural focus on the business travel segment — something that has differentiated the Milwaukee–based carrier from two generations of new entrants. Midwest’s own contemporaries — such as People Express — adopted low–fare strategies, grew too rapidly or chose the wrong markets, and most eventually failed. The ValuJet generation of 1993–1995 also came very close to extinction because they initially made the same mistakes (although many have now become profitable by changing their strategies).

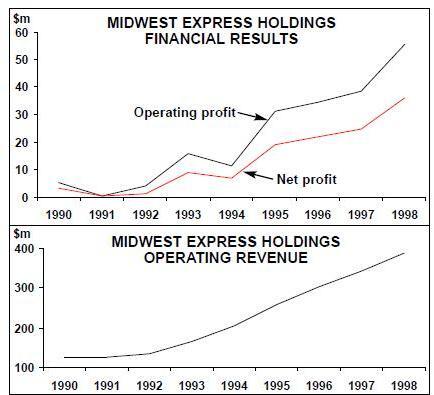

In contrast, Midwest Express continued steady, conservative growth and remained profitable through all the industry upheavals. It now has a 12–year unbroken profit record. In recent years it has posted double–digit annual growth in revenue and earnings. For 1998 the company reported a 44% higher net profit of $35.9m, representing a healthy 9.2% of revenues.

Midwest Express Holdings, which also includes commuter affiliate Astral Aviation (which operates as Skyway Airlines), went public in September 1995 in an $81m IPO. This was part of Kimberly–Clark’s policy of shedding non–core businesses and it meant no changes to leadership or strategy.

Eight months later, in May 1996, Kimberly–Clark divested itself of its remaining 20% stake in Midwest through another public offering. The company’s shares have performed well since being listed, more than doubling from $10-$15 in late 1995 to $30-$35 last summer and have since then largely maintained their value. There have been two 3–for–2 stock splits, in May 1997 and May 1998, and a common stock repurchase programme has been in place for a year or so.

Midwest’s balance sheet has traditionally been strong, but its cash position has been somewhat weakened by aircraft purchases over the past two years. It ended 1998 with cash reserves of $13.5m, down from about $32m a year earlier. But this is not believed to pose a problem because of continued strong profitability.

It is not easy to categorise Midwest. The investment community sometimes lumps it with the US regionals because of its corporate focus and strong profit growth, but it is really a “national”, with a fleet of DC–9 and MD–80s, a nationwide route network and annual revenues approaching $400m. But high cost levels (similar to those of US Airways) set it apart from other national carriers.

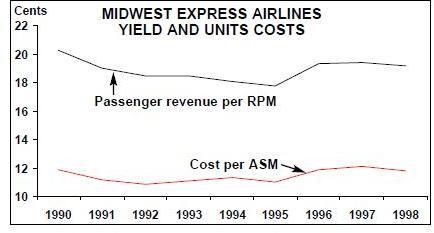

In a nutshell, Midwest’s financial success has been due to its ability to earn yields that are substantially higher than unit costs. It has continued to achieve passenger yields higher than 19 cents per RPM, while keeping its unit costs flat, at just under 12 cents per ASM (see chart, page 12). How does it do it?

Dedication to premium service

Midwest Express has maintained premium yields in part thanks to its unwavering dedication to the business passenger segment and service quality in general. It operates a single–class service featuring two–across leather seats — its DC–9s and MD–80s have about 20% fewer seats than normal. It provides first–class meals with free wine or champagne, spending twice as much on meals (about $10 per passenger) than the major carriers on average.

Midwest is also renown for providing passengers with personal attention, which is why it apparently spends a tremendous amount of time in the hiring process. In Southwest–style, the airline wants to make sure that all employees have a common vision and strives to maintain high staff morale.

Another important factor must be consistency — Midwest is permanently dedicated to improving the lot of its passengers, as opposed to making only sporadic efforts in that area. As a result, Midwest has won a long string of awards for service quality and innovation and has been named “the best airline in the US” by numerous consumer surveys.

The higher product costs appear to be more than offset by the premium yields, despite the fact that Midwest’s business fares look more like coach fares and that it offers fares for all categories of passengers (i.e. it carries some low–fare traffic). This is the really puzzling aspect of its strategy. As CIBC Oppenheimer’s Julius Maldutis, one of New York’s most experienced and respected airline analysts, put it in an interview for CNN: “I would have said it will never work, going totally against the grain ... if I had not seen it.”

Cost controls and efficiency

Midwest Express has kept its high cost levels in check through strict cost controls and constant efforts to improve efficiency. The mid–1990s saw substantial increases in aircraft utilisation and load factors. The average passenger load factor, at 65% in 1998, is now about ten percentage points higher than it was up to and including 1992. Last year saw major maintenance efficiency improvements thanks to an enhanced maintenance programme and expanded facilities at Milwaukee.

The emphasis has now shifted to improving efficiency through automation, new technology and process streamlining. Last year saw the introduction of automated systems, among other areas, for flight operations database and air cargo tracking. On–line booking and ticketing options have been developed. Electronic ticketing has been offered to passengers booking directly with the airline since late 1997 and was recently introduced at US travel agencies using Worldspan and SABRE, with Amadeus and Galileo following in the current quarter.

After four years of being virtually the lone holdout, in February Midwest Express finally followed the rest of the industry and cut travel agent commissions to 8% and imposed a $50 cap per round trip. The carrier said that the move was made in order to remain competitive in the face of rising distribution costs.

Serving the right markets

One thing that distinguishes Midwest from other post–deregulation new entrants is that it has obviously found the right markets. The strategy has been to serve selected major business destinations. The carrier will apparently only enter a market if it believes that the high–yield strategy can be successfully applied.

The network, centred on Milwaukee and Omaha, now covers 24 major destinations all around the US, including the key cities on both east and west coasts, plus Toronto. Most are served from the main hub at Milwaukee (Wisconsin), where about 80% of Midwest’s 2,200 employees are based, and a secondary hub at Omaha (Nebraska), which was opened in May 1994.

Midwest has benefited greatly from having its own feeder subsidiary. Astral (Skyway) began operations in February 1994 by taking over the feeder routes that Mesa had operated since 1989 under a five–year code–share agreement with Midwest. Astral currently serves 25 cities, providing connecting traffic to the larger carrier and point–to–point service in selected markets. Midwest has also benefited from limited code–share operations with American Eagle, introduced about a year ago in certain markets.

Midwest is fortunate in that it has no direct non–stop competition in the bulk of its markets. Cities like Milwaukee and Omaha have never captured the interest of the major carriers, which provide non–stop flights there only from their hubs. Yet those two cities are large population centres with strong and stable economic bases (including headquarters for numerous Fortune 500 companies) and good growth prospects.

The combination of lack of direct competition and Midwest’s high service quality, reasonable fares and adequate frequencies have given the carrier an enviably strong market position. New routes such as Kansas City–Raleigh/Durham, Omaha–Orlando and Milwaukee–Hartford (Connecticut) have performed well, and there are plans to expand service from the two hubs and from Kansas City.

This month (May) and in June the carrier will launch four daily Milwaukee–San Antonio flights via Kansas City, boost frequencies on services from Milwaukee to Toronto, Denver and San Francisco, increase capacity on the four–per–day Kansas City–LaGuardia flights by switching to MD–80s and upgrade Milwaukee–Hartford to six per day all–nonstop operation. Astral will play a key role in Midwest’s expansion strategy. The success of Omaha has led to tentative plans to announce another hub by the end of next year.

Fleet and capacity plans

Midwest has been disciplined enough to grow slowly. The early 1990s saw no capacity addition, and since 1993 ASM growth has averaged around 13–14% annually — a rate that may seem high but is not when considering the relatively small initial scale of operations. Until last year, Midwest’s jet fleet expanded at a rate of only 1–2 aircraft per year, from 12 in 1990 to 24 at the end of 1997.

The past couple of years have seen growth accelerate, following a 1996 decision to acquire a batch of high–quality, low–cycle ex–Garuda DC–9–32s and a September 1997 decision to buy eight ex–JAS MD–80s. The deliveries of the first three MD–80s boosted Midwest’s total jet fleet to 27 aircraft at the end of 1998, and the remaining deliveries will give it a 32- strong fleet at the end of this year (24 DC–9s and eight MD–80s).

Last summer the company decided to supplement Astral’s fleet of 15 leased Beech 1900Ds with up to 15 Fairchild Dornier 328 regional jets. A firm order was placed for five of the 32–seat jets plus 10 options.

Deliveries began in March and Astral expects to receive its third jet by the end of the current quarter. Most of the DC–9s are owned, though some were sold and leased back in late 1996 in the context of a refinancing of the entire Beech 1900D fleet. The MD–80s have been financed with a combination of debt and internal cash flow.

The fleet additions boosted Midwest’s capacity growth to about 20% in the first quarter, and the carrier expects 25% growth for the year as a whole. In the case of many other airlines that could constitute a warning sign, but Midwest’s record of managing growth and consistent profitability let it off the hook.

Labour and other challenges

Until four years ago, Midwest Express and Astral were totally non–unionised and enjoyed excellent labour relations. But that changed in the summer of 1995 when Astral pilots organised under ALPA. Since then Midwest’s pilots have followed suit and are now seeking federal mediation in what they regard as "stalled" initial contract talks (which only began last August).

Midwest’s 350 cabin attendants, in turn, are currently holding elections to be represented by AFA, saying that they have recognised the value that they bring to their employer. Ballots were mailed on March 25 and were due to be counted on April 29.

All of this, of course, is in line with the industry trend of labour demanding its share of the healthy profits, and it would have been surprising if Midwest had escaped it altogether. Like other carriers, Midwest may have to grant sizeable pay increases and then try to offset those with cost cuts in other areas.

All is not totally well on the revenue side either. In the past two quarters, Midwest’s yields declined much like those of the rest of the industry, despite its relatively low exposure to competition. As a niche–type operator it may always lead a relatively sheltered existence, but how long can lack of direct competition be sustained in so many major markets?

While there are no guarantees of continued strong earnings growth, analysts seem convinced that the only direction for Midwest Express is up. There is much confidence in the company’s longstanding top management, led by Tim Hoeksema as chairman and CEO. The team was recently strengthened with new senior appointments, desirable as the airline grows. The general feeling is that, like Southwest, Midwest Express will either overcome any future challenges or turn them into its advantage.

The current consensus forecast of six analysts reporting to First Call is that Midwest Express Holdings will increase its earnings per diluted share from last year’s $2.51 to $2.75 in 1999 and $3.04 in 2000. The shares are regarded as undervalued in the light of a P/E ratio of 11.3 (1999 earnings) and an expected 12% annual growth in earnings over the next five years.

| Current | Orders | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | ||||

| DC-9 | fleet | (options) | ||||

| 24 | 0 | |||||

| MD-80 | 3 | 0 | Five more second-hand MD-80s to | |||

| Beech 1900D | 15 | 0 | join fleet by end of 1999 | |||

| Delivery in 1999 | ||||||

| 328JET | 0 | 5 (10) | ||||

| TOTAL | 42 | 5 (10) | ||||

| $m | 1Q 1999 | 1Q 1998 % change | |

| Operating revenue | |||

| Passenger services | 88,862 | 79,201 | 12.2% |

| Cargo | 3,033 | 2,931 | 3.5% |

| Other | 6,986 | 6,280 | 11.2% |

| Total operating revenue | 98,881 | 88,412 | 11.8% |

| Operating costs | |||

| Salaries/wages & benefits | 29,021 | 26,303 | 10.3% |

| Fuel | 10,356 | 11,203 | -7.6% |

| Commissions | 7,068 | 6,625 | 6.7% |

| Dining services | 5,198 | 4,398 | 18.2% |

| Station & landing fees | 8,003 | 7,205 | 11.1% |

| Maintenance | 10,378 | 7,468 | 39.0% |

| Depreciation | 2,970 | 2,335 | 27.2% |

| Aircraft rentals | 4,890 | 4,711 | 3.8% |

| Others | 9,732 | 8,761 | 11.1% |

| Total operating costs | 87,616 | 79,009 | 10.9% |

| Operating profit | 11,265 | 9,403 | 19.8% |

| Other income/expenses | 100 | 325 | n.m. |

| Pre-tax profit | 11,365 | 9,728 | 16.8% |

| Net profit | 7,013 | 6,080 | 16.8% |

| Note: n.m. = not meaningful. | |||