Delta: tackling quality, union and alliance challenges

May 1998

Delta is in excellent financial shape but still struggling to restore service quality and employee morale after its earlier cost–cutting programme. It is expanding aggressively in Latin America and trying to retain its leading position on the North Atlantic. Will its new president and CEO Leo F. Mullin solve the quality problems, appease restless unions and forge a domestic partnership with United?

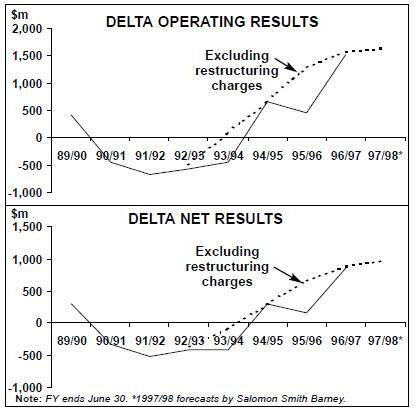

Only a few years ago Delta was on the brink of extinction with net losses of $1.7bn in 1991- 1994, the bulk of which was accounted for by its Atlantic division following the 1991 purchase of Pan Am’s European routes and Frankfurt hub.

After two years of heavy restructuring, the Atlantic routes returned to profitability in 1995. The division is now a solid performer, earning a $200m operating profit or a 12.7% profit margin in the first nine months of 1997.

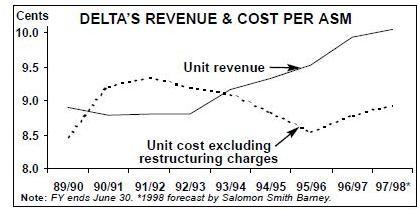

In April 1994 Delta launched an ambitious three–year cost–cutting programme, the "Leadership 7.5" project, which aimed to cut unit costs from 9.3 cents per ASM to 7.5 cents by the June 1997 quarter through staff reductions, outsourcing and route cutbacks.

The project turned out to be outstandingly successful. By the end of 1995, Delta had slashed its operating costs by $1.6bn. Its unit costs (excluding restructuring charges) fell to 8.33 cents in the June 1996 quarter, making Delta the lowest–cost hub–and–spoke major carrier in the US.

A four–year compromise deal with ALPA, signed in April 1996, contributed another $340m annual cost savings. Most significantly, the contract enabled Delta to set up a low–cost airline subsidiary, Delta Express, in October 1996, giving it a head–start over competitors in retaining and expanding operations in low–cost markets.

Delta never reached the 7.5–cent unit cost target, as the project was formally abandoned in summer 1996 due to the more pressing need to restore service quality and employee morale. The company had cut too deeply in some areas and its on–time performance had slipped seriously.

Delta was able to switch to a more balanced strategy, focusing on revenues while keeping tight controls over costs, because it had reached all of its financial goals: solid returns to shareholders, a lower debt structure and investment grade credit ratings.

In calendar–year 1997 Delta earned operating and net profits of $1.6bn and $934m respectively (including $52m special charges). Its profit margins (10.4% and 6.9%) were at the higher end of the range for the major carriers.

While Delta’s former CEO Ron Allen was credited for engineering the successful cost–cutting programme and restoring profitability, the persistent service quality and morale problems cost him his job in May 1997. Efforts had been made to correct those problems through in–sourcing, new recruitment in customer service areas and restoration of some of the pay cuts. But Delta still came ninth out of ten in the DoT’s on–time performance rankings in the year ended June 30, 1997.

One of the main reasons behind the appointment of an outsider, Leo F. Mullin, as president and CEO was clearly the hope of finding a fresh approach to handling customer service and employee morale issues. Mullin, a former banker, took up his position in August last year.

As expected, Mullin made service quality his top priority, announcing an agenda for reviving customer service within months of his arrival. Top management changes have been limited to the replacement of the CFO (November 1997) and the retirements of senior VPs for personnel and marketing in April. These moves reflect other new priorities at Delta: the need to deal sensitively with the interests of ALPA, deter further unionisation and secure alliance partners.

Service quality and labour issues

In November Delta unveiled plans to overhaul, modernise and streamline just about everything: lounges, gates, concourses and work areas at airports, boarding procedures, reservations lines and information technology systems. Mullin also decided to speed up a programme to refurbish aircraft interiors.

Delta now also expects to have state–of–the art technology capabilities within two years in MIS, revenue accounting, boarding and ticketing — an area where it has trailed competitors.

All of this will cost more than budgeted, but at this stage Delta still expects to retain its unit cost advantage over competitors. Its unit costs have been on an upward trend over the past two years, but so have those of the other major carriers.

But Mullin also faces the challenge of dealing with a restless workforce (an area where he is believed to lack expertise), making it all the tougher to retain the hard–won cost efficiencies. Delta’s pilots are unhappy about some of the concessions they made in 1996 and are now trying to secure good rates for flying the new–generation 737s. ALPA is also gearing up for new contract negotiations in the run–up to April 2000, when the wages will snap back to the 1996 pre–concession levels.

The past six months have seen much unionisation activity among Delta’s mechanics, ramp workers and cabin attendants (only pilots and a handful of dispatchers are unionised at present). In December TWU lost its petition to hold an election among ramp workers, but will no doubt try again. TWU and the Teamsters are wooing the mechanics, while AFA is gaining ground to organise Delta’s flight attendants.

Latin American expansion

Mullin’s second major move was to give the formal go–ahead to aggressive expansion in Latin America. In early December the carrier announced that it hopes to operate to 21 cities in the region within three or four years.

After serving only Mexico, Delta launched its first South American route (Cincinnati–Atlanta- Sao Paulo–Rio) in June 1997 and began to apply for route licences. Last year the region still accounted for less than 2% of its total revenues.

The initial phase of Delta’s expansion focuses on the Atlanta hub, which saw new non–stop 757 services to Guatemala, Panama, El Salvador and Costa Rica, as well as Caracas in Venezuela, in April. Atlanta–Lima operations will begin on July 1.

The carrier has also applied to serve Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia and Belize, subject to government approval, new bilaterals or amendment of existing ASAs. The services would mainly be operated from Atlanta and the necessary aircraft are already part of Delta’s fleet–purchase programme.

Delta is a little late in the game as Continental has already been aggressively challenging American and United in the US–Latin America markets over the past two years. In its efforts to become a major niche player, Delta will try to promote its main hub as a convenient alternative gateway, offering better facilities and faster transfer times than congested Miami. This is a reasonable strategy as about 55% of the Latin America traffic currently using Miami connects to other US points.

Delta can expect to make good profits in the region. In January–September 1997, it earned a $36.2m operating profit in Latin America, representing a 21.6% profit margin.

Access to additional markets will be gained through co–operation with Latin American carriers. Losing Varig (which defected to United’s Star Alliance in October) was a major blow, but Delta has since then secured code–share alliances with Transbrasil and Venezuela’s Aeropostal, as well as Air Jamaica. It is also expanding its successful four–year code–share relationship with Aeromexico.

But the biggest coup was to beat Continental to an equity stake in AeroPeru in March. Delta will acquire a 35% stake in the carrier and enter into a ten–year marketing alliance.

The deal is significant in that it will give Delta access to Lima, one of the most strategically located hubs in South America. It will also help cement the relationship with Aeromexico, which currently holds a 47% stake in AeroPeru, perhaps leading to an exclusive partnership in the vitally important Mexican market and an eventual equity stake in Cintra.

Key hubs and Delta Express

Over the past two years, Delta’s domestic strategy, like that of Continental and others, has focused on expanding and improving the economics of its main hubs: Atlanta, Cincinnati, Salt Lake City and New York (JFK).

The carrier’s biggest strength is its home base at Atlanta Hartsfield, where it accounts for about 80% of the traffic. Much of the new domestic expansion continues to focus on Atlanta.

The Cincinnati hub will see some expansion this summer, after cutbacks and realignment last year. The Salt Lake City hub will see some further rationalisation (termination of two routes) but new services to Detroit and Newark.

Much of the focus at JFK is on boosting feeder services to international flights, while Portland (Oregon) is now getting new connections that will feed to the new Japan services due this summer.

All the indications are that Delta Express has been a success. Its relatively limited scale of operation (about 150 daily flights at present, utilising 27 737–200s) means that it is not a major profit generator. But it has apparently exceeded all goals for operational reliability, customer satisfaction and profitability.

Delta Express features as a high priority in Delta’s strategic plans. In addition to enabling Delta to retain low–cost markets, it is used as a “laboratory for new ideas and innovative process” that can be applied to the whole company.

The venture is again being expanded this spring and summer, partly in response to new competition. For the first time, it will move west of the Mississippi, while some resources will be shifted from the Northeast to the Midwest. The summer schedule will connect 14 points in the Northeast, Midwest and Southwest with Orlando and four other Florida cities.

Asian struggles

Delta has not had much luck recently with its Asian partners. In November Singapore Airlines pulled out of the Global Excellence alliance. Although the two had code–shared only on the New York–Singapore sector, Delta had hoped to use SIA as an anchor for Asian expansion.

Then in March the carrier’s hopes of expanding ties with its existing code–share partner ANA were dashed when the Japanese carrier defected to United’s Star alliance. That left Delta with just two (lesser) code–share partners, Korean and China Southern, while its own Asian services cover only Japan, Korea and India.

On a positive note, Delta will be able to expand its co–operation with Korean under a USKorea open skies regime (an MoC was signed in late April). Also, the new US–Japan ASA will enable it to enter the Atlanta–Tokyo market (June 3) and link Portland with Osaka and Fukuoka at the end of October.

North Atlantic strength

Since the drastic early 1990s cutbacks, Delta has continued to fine–tune its European operations. In early 1997 it discontinued six intra–European and three transatlantic routes out of Frankfurt, where it had increasingly found itself overshadowed by Lufthansa and its alliance partners.

Parallel to the cutbacks, there have been efforts to strengthen the JFK hub with new European flights and more feeder services. This year Delta is terminating its unprofitable JFKBerlin and JFK–Copenhagen services and introducing services to Warsaw, Stockholm, Stuttgart and Barcelona. These moves have enhanced Delta’s already strong position on the North Atlantic and at JFK. In the third quarter of 1997 it earned the highest Atlantic operating profit among the US majors: $119.3m or 20.3% of revenues.

Codeshare co–operation with Swissair, Sabena and Austrian has developed rapidly since Delta secured antitrust immunity in the US for the Atlantic Excellence alliance in June 1996. There is no doubt that Delta has derived benefits from the alliance. However, the combine is nowhere near as powerful as the Star alliance, the possible BA/American combine or even Northwest/KLM. Add to that Delta’s current inability to serve Heathrow, and its strategic position on the North Atlantic looks weaker than what the scale of its own operations would indicate.

Now that the US–France bilateral (which will lead to an open skies agreement) has at last been finalised, Delta can proceed with its planned code–share with Air France, originally agreed on in 1994. But this deal is not exclusive as Continental has a similar agreement with Air France. Delta would appear to have two possibilities: either attempt to integrate Air France into its existing transatlantic alliance, which would be opposed by Swissair, or commit itself to a comprehensive and, hopefully, immunised alliance with Air France, which would probably involve abandoning its existing European partners.

Fleet restructuring

Delta is one of only two major US carriers (the other one is TWA) likely to achieve further significant cost savings through fleet restructuring and modernisation. There are still 131 727s and 42 L- 1011s in the fleet and, with eight distinct aircraft types, much potential for simplification.

Domestic requirements were taken care of in a $6.7bn 106–aircraft (767/757/737) order signed with Boeing in October 1997, for delivery in 1998- 2006. The aircraft will replace the 727s and the domestic L–1011s and create opportunities for "disciplined" growth.

The deal included 124 options and 414 rolling options (involving lesser commitment) covering the next 20 years. There is much flexibility to adjust the delivery schedule and substitute between aircraft types and models.

The process of replacing the international L- 1011 fleet began in January 1996, when Delta ordered 12 767–300ERs for transatlantic routes. Last November it placed a $1.42bn order for ten 777–200s (options in the October Boeing deal), for delivery by the end of 2000, and in March ordered another two. There are 20 options plus 30 rolling options slated for delivery by 2018. The 777s will essentially replace the MD–11s in transatlantic operations. The new Japan services will take up some of the European MD–11s. Delta expects to utilise mainly 757s and 767s in Latin America, plus possibly MD–11s and 777s in the longer term.

A link-up with United?

Delta’s market position is relatively strong because of its dominance at Atlanta, number one position at JFK and on the North Atlantic, good prospects as a niche carrier in Latin America and successful low–cost operation on the East coast.

But the proposed code–share and marketing alliances between the other US majors (Continental/Northwest and American/US Airways) have made it imperative for Delta to find its own domestic partner.

Delta had expected to link up with Continental but lost out to Northwest. But its talks with United now look likely to lead to a broad global partnership that will combine networks, marketing efforts and FFPs but involve no equity investment.

The two can claim perfectly complementary networks: Delta is strong on the East coast and in the South, United in the Midwest and West. European operations would be likely to be excluded initially, in order to avoid upsetting existing code–share relationships.

The alliance was expected to be announced in New York on April 24, but certain union–related issues still need to be worked out and there is no guarantee of a successful outcome. Because of its scope, the deal would also test the tolerance of antitrust authorities.

| Current fleet | Order | Options + rolling options | Delivery/retirement schedule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 727-200 | 131 | 0 | To be retired at about 10 per year | |

| 737-200 | 54 | 0 | ||

| 737-300 | 16 | 6 | ||

| 737-6/7/800 | 0 | 70 | (60+280) | Delivery in September 1998-2006 |

| 757-200 | 91 | 12 | (17+90) | Delivery in 1998/1999 |

| 767-200 | 15 | 0 | ||

| 767-300ER | 64 | 12 | (10+19) | Delivery in 1998-1999 |

| 767-400 | 0 | 21 | (24+25) | Delivery in 2000-2001 |

| 777-200 | 0 | 12 | (20+30) | Delivery in May 1999-2000 |

| MD-88 | 120 | 0 | ||

| MD-90 | 16 | 0 | ||

| MD-11 | 15 | 0 | To be retired as 777s delivered | |

| L-1011-1 | 21 | 0 | To be retired over next 1-3 years | |

| L-1011-250 | 6 | 0 | To be retired over next 1-3 years | |

| L-1011-500 | 15 | 0 | To be retired over next 1-3 years | |

| TOTAL | 564 | 133 | (131+444) |