Cash is King:

Aviation in Crisis

Mar/Apr 2020

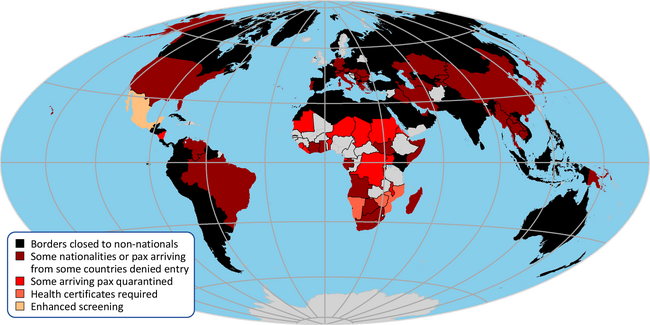

The speed at which the Coronavirus pandemic has developed world-wide has taken all but the most experienced epidemiologists by surprise. In a matter of only a few weeks the world’s economy has come to a sudden halt, extreme travel restrictions have effectively closed the borders to international travel — countries representing over 90% of air transport revenues are in lock-down — and the whole airline industry is in the process of closing down.

In the early stages of the crisis we, in common with other observers, likened its effects to a combination of the last three disruptive forces to face the industry — September 11, SARS and the Global Financial Crisis. But now, it is starting to look like a form of an apocalyptic World War III — with 185 countries involved (so far) and each with their own internal theatre of war.

The world’s stockmarkets have taken a battering since the end of February: New York’s Dow Jones and London’s FTSE indices are down by a massive 30%, the Nikkei and Hang Seng by over 20% since the beginning of the year. Airline and other aviation stocks have all been hit harder (charts and related graphs). This reaction from the markets appears natural — reflecting the seriousness of the impact of the crisis on travel related companies. But the extent to which the share price declines are matched across the board may be an irrational knee-jerk response: the best capitalised (but UK based) airlines in Europe are down by 70% with an average fall of 60% for the sector; all three majors in the US are down by 60%-70%; Chinese and Asia/Pacific airlines by an average 40%. The two major quoted hub airport groups in Europe — Aéroports de Paris and Fraport — have fallen by 50%, surprisingly similar to the declines seen by Air France-KLM and Lufthansa. Aircraft lessor share prices are down by around 70%, while the stocks of the two aircraft manufacturers, Boeing and Airbus, have moved in step and stand at 40% of the level at the beginning of the year.

As in war time, governments are throwing money at their economies. In the US, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to zero and started throwing money into the financial markets in the attempt to provide stability, while at the end of March President Trump was able to enact the suitably acronym-able Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to provide funds of a staggering $2tn in support to states, businesses, hospitals and households (equivalent to 10% of GDP). Many other countries have taken similar steps: the UK with a package equating to around 15% of GDP, Singapore 11%, Spain 17%, Australia 6%, and even Germany, abandoning its “zero black” rule is proposing spending 4% of GDP.

Demand for air travel has all but evaporated, and airlines have started grounding aircraft at a significant rate. As the chart shows, Europe is notably affected: the number of flights recorded by Eurocontrol has fallen precipitously since the beginning of March to a level 90% down on prior year levels. But as the chart suggests, this is only a third of the story world-wide: flights tracked by flightradar24.com are down by over 70% from the average in the first two months of the year. Although there are signs of a pick up in activity in China, this is still modest, and the country has imposed restrictions on international flights to avoid reimporting infections with a limit of one flight a week per destination.

This is a crisis of phenomenal proportions for the whole industry. IATA in its latest assessment posits that should the clampdown on travel last three months, and assuming a gradual return to the status quo (a V-shaped rebound seen in previous shocks unlikely given the recessionary impact on the world economy), the full year would still register a massive 38% annual decline in passenger traffic (in RPK terms) and a 33% decline in annual revenues. Up to now the only years that featured an annual reduction in passenger demand were 1991 (the Gulf War), 2001 (Sept 11) and 2009 (the GFC) with respective declines of -2.6%, -2.9% and -1.1%; while the largest decline in annual revenues was -16% in 2009 during the GFC.

Airlines

In this environment cash is king. Although the airline industry as a whole has registered strong levels of profits in the last few years, absolute levels of profitability has been concentrated with a handful of carriers, and the improvement in returns experienced by the top 30 airlines world-wide: as the chart shows, there is a long tail of marginally and severely unprofitable airlines. These top 30 too tend to have the best balance sheets with net debt to EBITDAR averaging 2.5 times against 5-6x for the rest of the industry.

As a general rule of thumb, it has been considered wise for an airline to have cash liquidity equivalent to at least 20-25% (or three months) of annual revenues. Some airlines round the world manage this, or better, depending among other things on their business models. However, as the chart shows, the median levels of cash before this crisis erupted stood around 15% of annual revenues, equivalent to less than two months of revenues. Even if the global lock-down lasts only three months, the implication may be that there will be many airlines who will not survive without significant levels of outside support.

But in this environment, even the large well-financed airlines will find it extremely difficult to guarantee survival.

In Europe, Lufthansa was one of the first to react — and with draconian measures. On the announcement of its annual results it revealed that while net bookings had been weak during January and February, they had plummeted since the extent of the pandemic in Italy had clarified and by the 9th March, the day before the results, had been 65% down on prior year levels.

Perhaps with a corporate memory of narrowly avoiding going bust in September 2001, Lufthansa announced that it would cut capacity by 90% from original plans and apply for Kurtzarbeit (support for short-time working) for a large proportion of its employees. And this was before the USA imposed travel restrictions on Atlantic services from Europe.

Of the top European carriers, Lufthansa had one of the lowest levels of liquidity entering this crisis with cash standing at only 14% of revenues, and clearly felt the urgent need to enter cash preservation mode. Management highlighted that with the grounding of its fleet around 60% of its operating costs would be mitigated, that it would cut back on all non-essential expenditure, defer capital spending and aircraft deliveries, and use its largely fully owned fleet as collateral to raise debt and important cash resources.

The rest of the airline industry worldwide perforce is now following Lufthansa’s example, urgently drawing on available credit lines where they can, and asking governments for help.

One of the greatest concerns, as cancellations exceed bookings, is how to cope with the the cash drain implied by refunds. All airlines use the advance payments they receive as working capital — to a greater or lesser degree depending on their business model (see table). And for some, as finances deteriorate, credit card companies increase the proportion retained until carriage has been performed.

In its latest assessment of the Coronavirus crisis, IATA points out that that the industry as a whole could have $35bn due for refund in the second quarter — 60% of their estimate of the total industry cash burn in the period. It is lobbying to allow airlines to provide refunds in vouchers rather than cash.

But the crisis is also having an equally disastrous impact on other elements of the industry.

Lessors

The aircraft lessors, had already seen requests from the Chinese and some SE Asian carriers for rental deferrals and rate renegotiations in February. AirAsia X for example stated as it announced a 60% increase in losses for 2019 — to RM-489m ($-118m) from RM-301m in 2018 — that it was looking to renegotiate a 30% reduction in rates for its 24 leased A330s (16 of which are currently parked), and defer delivery of its A330neos on order. The leasing companies are now rumoured to be getting similar requests from a large number of other carriers world-wide.

The lessors as a whole survived the various industry crises of the past forty years relatively unscathed. But they now control nearly 50% of the jet aircraft in service world-wide (twice the ratio they had in 2001). Apart from the pressure from their airline customers to defer and reduce payments, there is likely to be an increase in demand for sale and lease backs, at the same time that aircraft values will be plummeting. Their share prices have also plummeted since the beginning of the year (see chart).

AerCap, the largest player in the sector, at its full year results in February and then a JP Morgan conference in March appeared relatively relaxed. CEO Aengus Kelly said that in terms of the company’s exposure to China, “two-thirds of our revenue comes from the big three state-owned carriers. These airlines have been our partners for decades, and they will be our partners for decades to come. We will help them where we can through this very challenging period.” And then three days after that conference, AerCap drew down its entire $4bn unsecured revolving credit line (which will at least more than cover the $196m it spent in the fourth quarter of 2019 in share buy-backs).

Avalon, at the beginning of April, announced it had cancelled orders for four A330neos, 75 737MAXs (originally due for delivery in 2020-23) and deferred nine A320neos by six years. In total it has reduced its aircraft commitments for the next three years from 284 aircraft to 164. At the same time it also has drawn down its entire $3.2bn revolving credit facility. “We are currently facing the most challenging period in the history of commercial aviation”, said CEO Dómhnal Slattery, mentioning that 80% of Avalon’s customers had requested relief from payment obligations under their leases, and that these lessees accounted for more than 90% of its annual rental cashflow.

Governments to the rescue

This is a global crisis and yet unlike for example during the equally global financial crisis of 2008-09 there appears to be no international concerted action or leadership: each country is trying to deal with the problem on its own. But then, in the last five years there has been an increase in nationalist and populist politics and protectionism.

Even the fabric of the EU’s cohesion seems to be under further strain with individual European countries doing their own thing: and Hungary’s transition to government by presidential decree is seen in Brussels as contrary to EU rules. Indeed, the European Commission appears to be faffing around trying to create a role for itself in the crisis and work out what to do: it took a long time for it to realise the extent of the traffic downturn and relax the “use it or lose it” rules for airport slot allocation under which airlines would otherwise be forced to operate empty flights; its continued insistence on EU261 consumer protection regulations requiring cash refunds for cancellations has been unilaterally overturned by some individual nation states.

Faced with the effective closure of each nation’s (and the global) economy, there has been a desperate scramble to put packages in place to support all industries, their cashflow problems, and (primarily) employees and wages. In this light aviation, while being seen as an important strategic element of national infrastructure, is only a small part of the overall industrial problem.

In the US, within the CARES Act providing $2tn “relief”, a maximum of $208bn has been set aside for direct grants, loans and loan guarantees of which passenger airlines will have access to $50bn and cargo airlines $8bn. In addition air carriers are granted a holiday against aviation transport and fuel taxes.

However the terms of the relief package will have strings attached that may be unpalatable to some. The grants will be available for airlines to support their payroll (based on employee costs as reported in Summer 2019) as long as they do not impose involuntary furloughs or discontinue service to any airport served at the beginning of March until at least the end of September. Loans and loan guarantees would be subject to conditions that include that airline employees with earnings over $425k in 2019 will have their maximum total remuneration frozen for two years (unless subject to a collective agreement) and severance pay in that period would be limited to twice the total remuneration in 2019. Needless to say there could be no shareholder dividends or share buy-back programmes. Furthermore, the Government will have the right to participate in “the gains of the eligible business or its security holders through the use of such instruments as warrants, stock options, common or preferred stock, or other appropriate equity instruments”. In other words partial nationalisation.

In the UK the Government had considered providing an industry-wide package of support, but gave up when it found that the in-fighting industry players could not themselves agree to what form this should be. The Treasury has left the airlines to find their own private sources of cash, but stated that it would help individual carriers “as a last resort” on a case by case basis. In any case it had already allowed regional carrier Flybe (which had been financially challenged for many years) to go to the wall at the beginning of March. But the UK is perhaps unique. In the shenanigans over Brexit, it abandoned the requirement for substantial national ownership of airlines, leaving British airlines to prove that they were majority EU owned.

But there is also a political side to the equation. The Financial Times reported one government figure as having said: "There are obvious reasons why Virgin and easyJet aren’t the first on our wishlist of companies to help. There are the perennial questions over Richard Branson’s tax affairs and then there’s the fact that Stelios took that massive dividend [of £60m]. I’m not saying it’s impossible but the optics aren’t great.” Apparently, there are also feelings among Conservative MPs that supporting British Airways would mean giving money to a Spanish company, while most of the large airports are also majority owned by foreigners. At least IAG has cancelled its proposed final dividend for 2019.

Meanwhile, France and the Netherlands have said they will do “whatever it takes” to help Air France-KLM (in which the respective governments each hold 14% of the equity, and the French Government, courtesy of the Loi Florange, double the votes). One possible scenario appears to be that the operating companies would get state-backed loans, €4bn for Air France and €2bn for KLM, for the moment putting aside the two governments' disputes over the direction of the Group. But the French Transport minister, Jean-Baptiste Djebbari, said that the nationalisation of Air France “is one possibility among others that we are not ruling out”, while Pieter Elbers, KLM CEO, has felt it necessary to deny rumours of a break with the parent group saying “we are not working on disentanglement scenarios”. Interestingly, despite EU consumer law, the Netherlands has allowed refunds of cancelled tickets to be made in vouchers rather than cash.

A similar view is being taken by Germany, which has also likely to acquire Condor in the realisation that LOT’s agreed acquisition will no longer go ahead. At the same time Lufthansa is in negotiations with the German Government for state aid, and is said to be reluctant to consider any equity involvement. Meanwhile its financial management has been dealt a blow by the sudden immediate resignation of its CFO, Ulrik Svensson, for health reasons. But it is taking the opportunity to introduce a massive (overdue?) restructuring: decommissioning 40 aircraft (six A380s, 10 A340s,five 747s and 21 A320s) and closing Germanwings. When it emerges it will be 20% smaller.

In Italy, there is some strange irony that it has taken a global pandemic to “save” the perennially loss-making Alitalia. The Government finally gave up on attempts to sell the airline that has been in administration for the past three years by formally nationalising with plans to let it re-emerge as an almost irrelevant bit-player, operating a mere 25-30 aircraft (down from 93) and only 3,000 employees (12,000). The European Commission has stated that it would approve nationalisation if done “at market prices”, even while it continues an investigation into possible illegal state aid over the past three years. Brussels really doesn’t have a clue.

Meanwhile in Singapore, SIA managed to launch a S$15bn rights issue, supported and underwritten by state holding company Temasek and its 52% stake. In contrast in Australia, while airlines have been granted exemption from fees, the Government has baulked at acceding to a request from Virgin Australia for support seemingly deciding that although structurally it wants a competitive (duopolistic) domestic aviation market, should Virgin Australia fail, some other carrier would come in to take its place.

Environmental Considerations

The industry has spent a considerable amount of time and effort in recent years to try to show its commitment to reducing its net carbon footprint. While the debate has been most apparent in Europe, with the development of the flygskam movement, the issue of global warming is being taken seriously. One of the more interesting elements of the debate in the US over financial support to the airlines was an attempt by Democrats to table amendments to the CARES Act that would require stiff targets for the reduction of emissions as a price for financial support to airlines.

In a way, the same matter is a restraining factor in Europe against any political move for renationalisation (except in Italy).

Intriguingly for the industry, its own international remedy, CORSIA (see Aviation Strategy, June 2019), is designed to stabilise net carbon emissions at 2020 levels (based on the average emissions for 2019-2020). If, as now seems likely, the net emissions this year will be significantly lower than would normally have been expected, the restraints on air traffic growth in the medium term will have increased substantially.

| Cash | Advance Sales | Cash burn | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ¤m | % Revenues | Available | Total Liquidity | ¤m | % Cash | ¤m per day | months | |

| IAG | €7,350 | 36% | 1,900 | 9,250 | 5,486 | 59% | 30 | 10.1 |

| Lufthansa Group | €4,300 | 14% | 800 | 5,100 | 4,071 | 80% | 47 | 3.6 |

| Air France-KLM | €3,715 | 20% | 1,800 | 5,515 | 3,289 | 60% | 36 | 5.2 |

| Ryanair | €3,578 | 45% | 3,578 | 1,309 | 37% | 9 | 14.0 | |

| easyJet | £1,576 | 31% | 417 | 1,993 | 1,069 | 54% | 8 | 8.2 |

| Wizz | €1,501 | 54% | 1,501 | 420 | 28% | 3 | 15.6 | |

| Norwegian | Nkr3,096 | 7% | 3,096 | 6,107 | 197% | 58 | 1.8 | |

| Virgin | £392 | 14% | 392 | 619 | 158% | 4 | 3.4 | |

| Delta | $2,900 | 18% | 5,600 | 8,500 | 5,116 | 60% | 55 | 5.1 |

| American | $3,826 | 15% | 3,200 | 7,026 | 4,808 | 68% | 58 | 4.0 |

| United | $4,944 | 20% | 3,500 | 8,444 | 4,819 | 57% | 53 | 5.3 |

| Southwest | $4,100 | 23% | 1,000 | 5,100 | 4,457 | 87% | 27 | 6.4 |

| April Capacity cuts | Aircraft currently parked† | Total fleet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Canada | Up to 90%. 16,500 staff on furlough | 46 | 189 |

| Air France-KLM | 70% to 90%, Early retirement B747, grounded A380s | 174 | 543 |

| Air New Zealand | Long haul 95%; domestic 30% | 11 | 114 |

| American | International 75%, Parked “nearly all” widebody fleet. | 287 | 947 |

| Cathay Pacific | 96%. Network cut to three flights a week on only 12 international and 3 Chinese destinations | 31 | 152 |

| Delta | International 21%-25%; domestic 10%-15% | 351 | 913 |

| LATAM | 95% group-wide. Peru, Ecuador, Colombia closed passenger operations. International limited to siz routes from Santiago and São Paulo | 181 | 332 |

| Lufthansa | Long-haul 90%; Europe 80%. 31,000 staff on Kürtzarbeit. 700 out of 760 aircraft grounded. Swiss: 80% cut (may go to 100%). Austrian, SN Brussels closed operations. | 585 | 757 |

| easyJet | Closed passenger operations | 334 | 337 |

| Emirates | Closed passenger operations | 228 | 269 |

| Finnair | 90%. Network reduced to 20 routes | 12 | 72 |

| IAG | At least 75% | 296 | 587 |

| Norwegian | 85%. Lays of 90% or workforce | 127 | 146 |

| Qantas | International 100%; domestic 60% | 54 | 264 |

| Ryanair | 99% | 73 | 468 |

| SAS | “Most” of its schedule. 90% of employees furloughed | 67 | 153 |

| Singapore | 96% | 48 | 185 |

| Southwest | 40% | 123 | 742 |

| United | International 95% | 248 | 800 |

| Virgin Atlantic | Up to 85% | 11 | 42 |

| Westjet | International 100%; domestic 50% | 12 | 126 |

| Wizz Air | 85% and may go to 100% | 56 | 121 |

Notes: † at 31 March 2020

Source: Eurocontrol

TWO MONTHS OF REVENUES

Source: IATA, based on a sample of airlines in each region.

Source: IATA

Source: Flightradar24