Norwegian:

Global LCC

March 2017

Norwegian Air Shuttle proudly announced that in 2016 it generated its best results ever. Revenues topped NOK26bn ($3bn) — up by 16% year-on-year — and published operating profits grew five-fold to NOK1.8bn ($215m) as did net income to NOK1.1bn. Norwegian, Europe’s third largest LCC has been embarking on an audacious plan to take the low cost revolution to the long haul markets and is now set to enter a period of major expansion in that arena — enough to worry the established long haul network players and threatening to make the long-haul low cost model the new disruptive force in the industry.

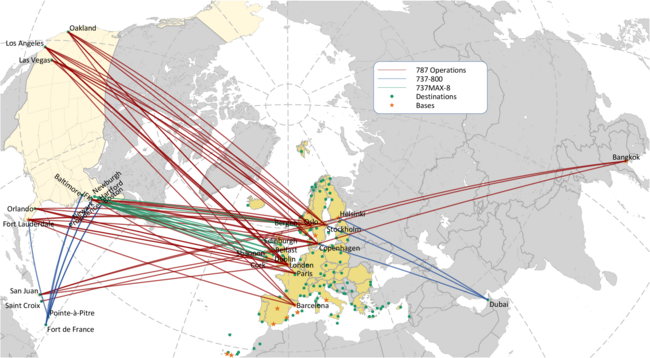

Norwegian originally started long haul operations in 2008 flying to Dubai from Oslo, Copenhagen and Stockholm using 737-800s. It started its exploration into the long haul widebody markets in 2013 — aiming to take advantage of Norway joining the EU-US open skies agreement in 2011 — with the delivery of 3 787-8 aircraft (supplemented by leased-in A340s) operating initially from the three Scandinavian capitals to Bangkok, New York and Fort Lauderdale.

In the first year of operation it carried just under 200,000 passengers on a load factor of 89%. By the end of 2016 it had 12 787s in its fleet on which it had carried 1.9 million passengers (6% of the group’s total 29.3m pax) on a 93% load factor. The route network had been expanded to include Los Angeles, San Francisco’s Oakland airport, Las Vegas, New York, Orlando and Boston, while it started long haul flights out of London Gatwick in 2014 and Paris in 2016.

It has taken a highly innovative approach to establishing its route network. Firstly, it has set up bases at the other end of the route (eg in New York, Bangkok and Fort Lauderdale) and appears to have received temporary dispensation from the requirement to staff Norwegian registered aircraft with Norwegian nationals.

Secondly, it has established subsidiary airlines with AOCs in Ireland and the UK, partly to regularise its employment ambitions but more importantly to enable it to access international route rights from those countries otherwise denied to it by existing Scandinavian bilateral air service agreements: as an effective EU carrier under the EU-US open skies agreement it is able to operate routes between any European and US points, but with its Norwegian AOC is limited to operate routes to other countries (not covered by an EU horizontal agreement) according to its home country’s existing bilaterals.

Thirdly, it has imaginatively developed routes to help offset the seasonal imbalance on its short haul European operations that fit in with its long haul bases. For example it operates winter routes from the French Caribbean, Guadeloupe and Martinique (which amazingly are part of the EU and therefore come under the US-EU open skies agreement) using 737s to Boston, New York and Baltimore (this year adding services to Fort Lauderdale). In this recent winter season, it took a step further and operated charter services for local travel service companies from Milwaukee and Chicago Rockford Airport to the Caribbean and Mexico.

This expansion has taken place despite the delay in getting approval from the US to operate flights to the US under the Irish granted AOC (Norwegian Air International) or the UK AOC Norwegian UK. The company applied in 2013 for a US foreign air carrier permit for NAI but encountered belligerent opposition from the major US carriers and employee groups with the complaint that the establishment of an airline in Ireland or the UK was, as ALPA has stated, “in order to take advantage of these countries’ less-restrictive labor and regulatory laws” and equivalent to the flags of convenience “that led to the destruction of the US shipping industry”.

The US DoT gave tentative approval to the Irish subsidiary in April 2016 and finalised the approval in the last days of the Obama administration stating, seemingly reluctantly, that “regardless of our appreciation of the public policy arguments raised by opponents, we have been advised that the law and our bilateral obligations leave us no avenue to reject this application”.

The airline’s British subsidiary, Norwegian UK, started its application to the DoT for an exemption and permit in December 2015, but in June last year was denied exemption while the final decision on NAI was pending.

This has all now become a little more complicated following the UK referendum and British decision to leave the EU. There is a distinct possibility that the UK will no longer have access to the European Common Aviation Area possibly resulting in the need for any UK airline to prove it has majority of UK rather than European shareholders.

Subsequently, the UK would presumably fall out of the EU-US open skies agreement and the British Transport minister Chris Grayling recently stated that it was “vital that we seek to quickly replace EU-based third-country agreements, like the US and Canada … that’s something we are working on at the moment”.

Growth acceleration

Norwegian is planning a significant increase in the rate of growth in the next couple of years. The company is set to add nine 787-9s in 2017 and a further 11 in the following year giving it a fleet of 32 by the end of 2018. It shows plans suggesting that the total capacity in terms of ASKs represented by the Dreamliners will grow by 60% in the current year and double in the next. It is also taking delivery of the first six 737Max-8s (it has 108 of the type on order with an additional 92 options) and 17 new 737-800s (four of which are for replacement). This will lead to a 20% capacity increase in 2017 for the narrowbody fleet and a group combined total growth of 30%.

While adding frequency to existing 787 routes it is also starting services from Barcelona to Fort Lauderdale, New York, Los Angeles and Oakland; Gatwick and Copenhagen to Oakland.

Norwegian has also announced it will start services in June using the new 189-seat 737 MAX-8s from Cork, Shannon, Dublin, Edinburgh, Bergen and Belfast to secondary airports on the US East Coast: Providence (Rhode Island, 40 miles/60 km from Boston), Stewart Airport (New York State, 60 miles north of Manhattan), and Hartford (Connecticut, 100 miles midway between the other two). These are all relatively small airports — Providence and Hartford each respectively with 3.65m and 2.93m terminal passengers last year while Stewart saw a throughput of only 280,000 — where landing fees are likely to be quite a bit lower than at the primary airports. Comparing airport charges is an arcane art but, as an example, Stewart charges $1.53 per thousand pounds of MTOW compared with $6.33 at JFK and $8.15 at Newark.

The company has generated a high level of publicity and interest from offering low lead-in fares below £100/€100 one-way, possibly a bit more than is warranted. The level of industry attention is perhaps indicative of the way that the established carriers see this model as a serious potential threat when Norwegian has a tiny portion of the market. From our analysis of the schedules, Norwegian will have a 1.5% share of the total number of seats on transatlantic routes which compares with a 5% share for other low cost operators and a 9% share for the superconnectors while the rest is effectively sew up by the three ATI-immunised joint ventures.

Nevertheless, imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery and British Airways has reacted to Norwegian’s expansion in Gatwick by increasing seating density and flying head-to-head in direct competition, while IAG is setting up a new low cost airline, Level, using high density A330s and based initially in Barcelona (where Vueling should be able to provide feed). Willie Walsh, IAG’s CEO explains: “having learnt the lessons of being slow to adapt many years ago to shorthaul low cost, IAG is determined to play its part in the longhaul market”.

"Best ever annual results"

The 2016 results were good, for Norwegian. The NOK1.1bn net profit came on the back of an 18% increase in capacity (in ASK terms) in the year, a 20% growth in RPK (and a 1.5 point increase in load factor to 88%). Yields fell by 5%, unit revenues by 3% and unit costs by 3% year on year. The total number of passengers carried grew by 14% to 29.3m while the average stage length increased by 5% to just short of 1,500km. The results were helped by lower fuel prices (total fuel costs were down by 2% year on year despite the growth) but flattered by significant swings in non-operational accounting items. Underlying operating profits nevertheless increased by 50% to NOK1.24bn up from NOK822m. This however represents a relatively poor 4.8% operating margin and a return on invested capital of only 4%.

The balance sheet meanwhile remains weak (see table). Shareholders' funds improved to NOK4bn, but with NOK6.5bn in capital expenditure in the year against operational cash flow of only NOK3bn, total debt increased by NOK3.9bn and adjusted net debt (including capitalised leases) stood at ten times the net asset value.

A substantial portion of the balance sheet relates to future aircraft deliveries: not only is there NOK7.1bn in pre-delivery payments accounted for in the fixed assets (24% of the total) but 7% of the gross debt, or NOK1.6bn, relates to (presumably) relatively expensive PDP debt finance.

Capital expenditure is set to continue at a high rate. Along with the aircraft acquisitions planned for its own fleet it will be taking 3 A320neos into its Irish based leasing company (Arctic Aviation Assets) in 2017. The first two of its 100 aircraft order (+100 options) were delivered in 2016 and leased out to HK Express, as will these next three. Seven further A320s originally due for delivery in 2017 have been delayed.

The company is guiding to capital expenditure of $1.8bn and $2.1bn for each of 2017 and 2018 for deliveries and pre-delivery payments. The management however appears sanguine about the future ability to fund this spending and state that “financing is on track”. (It at least has the opportunity to pursue ExIm and ECA guaranteed financing which already account for the funding of a third of the fleet).

It is also guiding to a forecast of unit costs of 39-40 øre per ASK for 2017, a modest 4% decline from the 41 øre achieved in 2016 despite the strong anticipated growth. Part of this is due to the understandable build up of expenses in the ramp-up of development in intercontinental services over the next two years. At the same time unit revenues appear to be under severe pressure having expected to have fallen by 13% and 11% in the first two months of this year (albeit the worst seasonally speaking).

Bank Norwegian

Bjørn Kjos (Norwegian’s founder and CEO) is one of those innovators that ignores established perceived wisdom. No other airline would have thought of vertically integrating a bank as a strategic play, but ten years ago he established Bank Norwegian as an internet bank and credit card issuer. Part of the reason for the move was to get around Norway’s ban on the use of frequent flyer loyalty programmes (following the takeover by SAS of Braathens SAFE six years previously) in being able to offer loyalty points to credit card holders for flights on Norwegian. It moved into Sweden in 2013, and Denmark and Finland in 2015.

It ended 2016 with 120,000 depositors, 150,000 loan takers and 675,000 credit card holders and a solid balance sheet. Co-located in the Norwegian Air Shuttle head-quarters in Oslo Fornebu, it only employs 62 full-time equivalent personnel but generated profits for the year ended December 2016 of NOK960m with assets of NOK30bn and equity of NOK3.3bn. Not far short of Norwegian’s own figures.

Norwegian Air Shuttle was only allowed to retain a 20% stake. The bank was listed on the Oslo stock exchange in 2016 and currently has a respectable market capitalisation of NOK13.9bn ($1.6bn) — 50% higher than that of Norwegian Air Shuttle’s own market cap. Norwegian’s 20% stake would provide an additional NOK2.5bn to its own equity and improve its own balance sheet ratios. Part of this valuation however must relate to the close brand relationship between the two companies.

Conclusions?

Another quote from Willie Walsh: “I like what Bjørn Kjos has done and I have great admiration for him. I think he has yet to crack the profitability bit, but margins are improving and they are generating cash.”

The highly-competitive airline industry thrives on innovation and Norwegian’s management has shown its ability to think laterally. First-movers don’t always succeed; we hope this one will.

| NOKm | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Fleet and property | 24,812 | 30,100 |

| of which Aircraft PDP | 5,939 | 7,156 |

| Investments | 910 | 1,430 |

| Intangible assets | 800 | 440 |

| Fixed assets | 26,523 | 31,969 |

| Cash etc | 2,454 | 2,677 |

| Other current assets | 2,657 | 3,117 |

| Current assets | 5,111 | 5,793 |

| Short term debt | (3,041) | (4,769) |

| Other current liabilities | (7,692) | (8,642) |

| Current liabilities | (10,733) | (13,411) |

| Net Current Assets | (5,622) | (7,617) |

| Total assets | 20,901 | 24,352 |

| Long term debt | 16,543 | 18,706 |

| Other long term liabilities | 1,392 | 1,597 |

| Equity | 2,965 | 4,038 |

| Minorities | 11 | |

| Shareholders’ funds | 2,965 | 4,049 |

| Total Liabilities | 20,901 | 24,352 |

| Adj Net debt/equity | 1175% | 1075% |

| Adj Net debt/Capital employed | 138% | 140% |