Finnair: East by

Northeast

March 2016

Finnair’s share price doubled over 2015 as the airline focused on its core business and concentrated on profitability rather than growth. Can the momentum of Finland’s flag carrier continue through 2016 as it starts a new growth phase and, if so, could it prove a valuable acquisition for a larger airline?

Based at Helsinki’s Vantaa airport, Finnair was launched as far back as 1924 — making it one of the oldest airlines in the world — and though it has had ups and downs, under state control it has happily stuck to its mission of serving its tiny home market domestically and internationally with reasonable success ever since.

Its core disadvantage, however, is its location at the northern extreme of Europe, which means that it struggles to attract any through passenger traffic in Europe other than to/from the Nordic countries and east/south to the Baltics and parts of Russia. That tough geographical positioning is reflected in its financials, where it has lurched between profitability and loss for a number of years.

In 2015, however, despite reporting just a 1.7% increase in revenue to €2.3bn, Finnair turned an operating loss of €36.5m in 2014 into a €23.7m operating profit in 2015. Similarly, an €82.5m net loss in 2014 became a €89.7m net profit last year.

The reasons for that creditable result (and the subsequent improvement in share price — see chart) are multiple. At a macro level Finnair has benefited from an upturn in the Finnish economy — after three years of recession, GDP grew by 0.4% in 2015. More importantly perhaps, cost-cutting has been a key priority for many years, initially starting after the post-September 11 traffic downturn, with — for example — its group workforce steadily shrinking from just under 10,000 in 2003 to 4,900 as at the end of 2015. However, that has led to significant disputes with unions over the years, either directly or as a by-product of clashes between unions and the state over collective labour agreements and conditions. Nevertheless, the necessity to reduce costs remains — as can be seen in the chart, there is no permanent clear gap yet between unit revenue and costs.

Asia routes

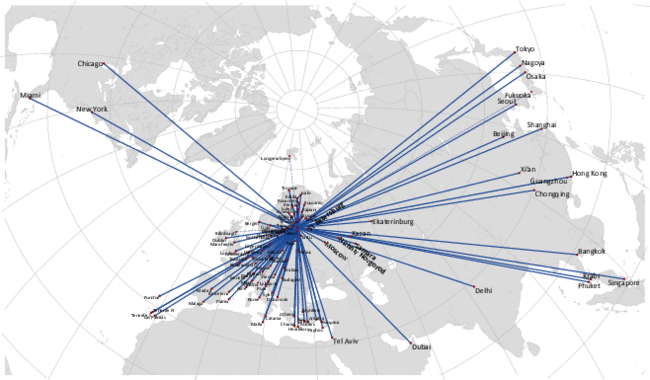

Just as important as cost measures is the continuing attempt to turn Finland’s geographical isolation within Europe into an advantage in terms of its proximity to Asia, where the fastest connections between many European cities and what it calls “Asian megacities” fly over Finland and then Russia. This has been an aim for Finnair for several decades (its first Asian route, to Bangkok, started in 1976), but in May last year, as part of a strategic review, Finnair adopted a new target of doubling traffic to/from Asia by 2020 compared with the 2010 level.

Currently the airline operates to 15 Asian cities in nine countries (both leisure and business destinations) and this May it will boost the network through new routes to Fukuoka in Japan and Guangzhou in China. At the former Finnair will benefit from its close relationship with Japan Airlines, which is a fellow member of oneworld.

Finnair’s relative proximity to north-east Asia means that it can operate routes with aircraft on a 24-hour round-trip rotation, which it points out “enables very high aircraft utilisation and reduces the need for additional crews due to flight time restrictions”. From a passenger point of view, the routes are around two hours less on average compared with one-stop flights from European hubs (though clearly this varies considerably depending the specific airport the comparison is with), and more than four hours shorter compared with flights connecting through the Gulf hubs.

But while Helsinki airport has three runways and relatively short connection times, it’s a tough sell to persuade European travellers not based in northern Europe to connect to Asia though Finland. The traditional Mercator projection of the world perpetuates a concept that to go East you travel towards the East, whereas the great circle and therefore shortest route from the center of European population can well be to the North and over Helsinki anyway. Another challenge here is the faltering economies of several countries in Asia, not least China, though Finnair says it has not seen any signs of weakening Chinese demand as yet.

Nevertheless, last year Asian routes accounted for half of Finnair’s total traffic, and the airline says that in total it has an approximate 4.6% market share of traffic between Europe and Asia — though that was down from 4.8% as of 2014, which perhaps indicates the level of competition that Finnair faces.

Finnair’s only other long-haul routes are to North America (to New York, Chicago and Miami), but although these are doing well in the premium segment, Finnair says that in economy it “suffered from intense competition and overcapacity” in the fourth quarter of 2015. A note released by HSBC Global Research in February says that it “harbours some concerns about the limited feed available for Finnair’s US flights, given Helsinki’s geography and the poor economics of Russia, which is a natural feed market for Finnair’s US flying”.

A350 investment

Altogether the long-haul network is served by a fleet of 16 aircraft, comprising eight A330s, five A340s and three A350s. The fleet is being renewed through the 297-seat A350 XWB, 19 of which were on order (with 11 placed in 2007 — making Finnair the European launch customer for the model — and eight more in 2007), with three delivered in 2015 (the first in October) and four others arriving this year, four in 2017 and the remaining eight coming by the end of 2023. The remaining five A340s will be phased out by the end of 2017, four of which are being sold back to Airbus.

On short-haul Finnair operates to around 60 destinations in Europe with 30 owned and leased A320 family aircraft, but although this fleet has an average age of more than 12 years it has no firm orders at present. Instead Finnair’s strategy in Europe currently revolves around operating larger aircraft to fewer destinations, and the first stage of this involves the lease of two A321s that arrive in May this year (each on one year contracts), before leasing four A321s (on eight year terms) from BOC Aviation for the first-half of 2017. Finnair will also add extra seats to 22 A320 family fleet in 2017 by reducing storage and technical space at the front and aft of aircraft; this will increase capacity by between six to 13 seats for each aircraft.

For its domestic network (which unsurprisingly is loss-making) and some European routes Finnair contracts Vantaa-based Nordic Regional Airlines (Norra) to operate on its behalf, and the Norra fleet comprises 12 ATR 72-500ss, two E170s and 12 E190s.

Norra was previously known as Flybe Nordic, which was created in 2011 when Finnair and Flybe bought respective 40% and 60% stake in Finnish Commuter Airlines (at a total price of €25m), which was then renamed Flybe Nordic. However, the airline’s losses persuaded Flybe to exit and sell its 60% stake for just €1 to Finnair in March 2015 (after which it was renamed as Norra), although this was a temporary arrangement before that same 60% stake was sold on to two Finnish companies — StaffPoint Holding (with 45%) and Kilco (15%) — in November 2015 for the same €1 price. StaffPoint is a staffing/recruitment agency with 15,000 employees, while Kilco is an investment company that part-owns StaffPoint.

As for cargo, Finnair runs hubs at Helsinki, Brussels and London, with all its cargo capacity now in the belly of its passenger fleet after discontinuing separate cargo freighter operations in 2014 and after Helsinki-based Nordic Global Airlines (in which Finnair owed 40%) ceased business in May last year. An exception to this is a wet-leased freighter that the company operates as a cargo "air-bridge" to connect its network with that of BA in London integrating the Asian flows with IAG Cargo. Finnair meanwhile is investing €80m into a new cargo terminal at Helsinki over the next few years, which will replace its present cargo terminal that will be decommissioned in 2017.

However, cargo is a tricky business for Finnair at the moment as there is significant overcapacity in the market between Europe and Asia, and as a result the airline said it experienced ”further weakened average yields and load factors” in Finnair’s primary markets for cargo traffic in 2015. Finnair’s total cargo tonnes carried fell 12.4% last year, cargo unit revenue was down by 7.5%, and cargo revenue fell a substantial 20.6% to €183.7m.

The airline business (both passenger and cargo) accounted for 91.1% of all revenue in 2015 — the rest is made up of Travel Services unit, which comprises tour operators and travel agencies, and which experienced a fall at both the revenue and profit level last year.

A bright future?

Pekko Vauramo, CEO of Finnair, says that “we are heading in the right direction”. While this is broadly true, significant risk must be present from increasing competition.

Within Europe Finnair — like all other flag carriers — faces intense competition from LCCs, although its northern position means that if faces no direct competition from easyJet, and Ryanair operates routes only from Tampere (in southern Finland) to Bremen and Budapest. The main LCC competitor is Norwegian (see Aviation Strategy, December 2015), which operates from Helsinki to 28 destinations directly, of which 24 are international and four domestic (Ivalo, Kittilä, Oulu and Rovaniemi), and from Oulu to two international destinations. As a result, Norwegian has an approximate 12% market share at Helsinki airport, and given its fares structure is Finnair’s fiercest competitor, ahead of SAS, which has just eight routes between five Finnish airports and its hubs at Stockholm, Oslo and Copenhagen.

Finnair says it has a 57.9% share of the market in European traffic to/from Helsinki last year — which rose by 5.5% compared with 2014 — but share isn’t everything, and it’s critical that Finnair continues to maintain its average yield, as it has done over the last couple of years following a worrying period of decline through 2012 and 2013 (see chart).

Finnair does have some room for manoeuvre given that it’s strong in terms of the balance sheet. As at the end of 2015 Finnair’s interest-bearing long-term debt stood at €271m — 19.8% down year-on-year — while cash and cash equivalents totalled €280.5m, some €197m higher than 12 months previously. In October last year strengthened its finances by issuing a €200m bond and selling and leasing-back two A350s with GECAS. Further A350s will be sold and leased-back with GECAS in 2016 and 2017.

2016 will be crucial for Finnair, as the modest capacity growth of last year (just 3.1%) will be replaced by significant growth. HSBC forecasts it will be around the 10% mark thanks to the delivery of more A350s, new Asian routes and an expansion of the short haul network. HSBC believes that underlying profitability should rise in 2016 because although yield will fall due to competition, unit costs will drop by almost 9% year-on-year, thanks mainly to falling oil prices. Those oil costs will compensate for rising expenditures elsewhere; for example, the arrival of the A350s is leading to a significant expansion of long-haul staff recruitment, with 100 new pilots and 300 new cabin crew members arriving from this year onwards.

Yet the macro-economic oil situation should be seen as nothing more than a short-term phenomenon (as very few people argue that low oil prices are with us permanently), and once that compensating factor evaporates — and with limited scope for further significant non-fuel cost savings giving Finnair’s structurally high-cost location — Finnair will inevitably be stuck with the underlying problem of compensating for unrelenting yield pressure.

To be fair, it’s a risk that Finnair management must be fully aware of, and that’s why the airline is pushing ahead in other areas, such as ancillary business; ancillary service revenue per passenger grew 23.7% in 2015 compared with 2014, to €10.2 per passenger, bringing in total revenue of €104.6m over the year.

Value to IAG?

Though quoted on the Helsinki stock exchange since 1989, the Finnish state still owns 55.8% of the airline, and the government would have to change its status as a “national strategic asset” before it could sell its majority stake.

There has been growing speculation that such a move may be imminent, and that if it does then fellow oneworld member IAG is likely to be at the head of the queue to buy the state’s shareholding. Yet it’s hard to see what value Finnair would really deliver to IAG. Even if it can establish a sustainable gap between unit costs and revenue, given its tiny home market it will never be a generator of substantial cash and profits for IAG.

Essentially that leaves Finnair’s share of the European market into north-east Asia as the main rationale for a purchase, but that share is relatively small and totally dependent on Russian over-fly rights that potentially could disappear at some point (particularly given Russia’s frosty relationship with the UK at present). In any case, what further revenue could be driven by buying Finnair that isn’t or couldn’t be achieved by oneworld and the existing joint venture it and IAG have with JAL on Europe-Japan routes?

In a sense the logic for IAG acquiring Finnair is a negative one, in that while buying Finnair might not bring huge benefit to IAG, if it fell into the hands of Star or SkyTeam that would be problematical to say the least. Not only would it create a hole in the Nordic region for oneworld, but if Star acquired Finnair that alliance would dominate the Nordic region (thanks to the combination of SAS and Finnair, not to mention Lufthansa just to the south). The situation wouldn’t be much better if a SkyTeam member bought Finnair, as Aeroflot and Finnair would have a grip on the fastest routes into north-east Asia.

Fear of losing an asset to a competitor is never a great rationale for an acquisition, but that logic may prove just strong enough for IAG to acquire Finnair if/when the Finnish state puts it up for sale.

| In service | Orders | |

| A319 | 9 | |

| A320 | 10 | |

| A321 | 11 | |

| A330 | 8 | |

| A340 | 5 | |

| A350 | 3 | 16 |

| Total | 46 | 16 |

Note: Equidistant map projection centred on Helsinki. Great circle routes appear as straight lines.